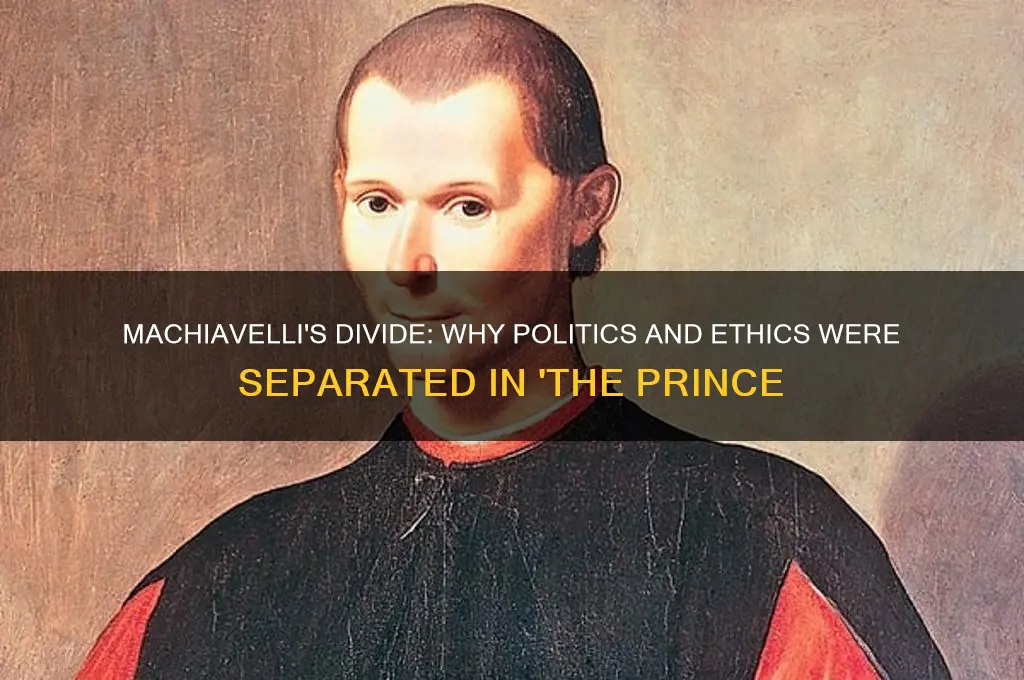

Niccolò Machiavelli, in his seminal work *The Prince*, fundamentally separated politics from ethics, morality, and religion, arguing that effective governance requires a pragmatic, often ruthless approach. He posited that political leaders must prioritize stability, power, and the preservation of the state above all else, even if it means employing deceit, coercion, or force. Machiavelli’s separation of politics from traditional moral frameworks stemmed from his observation of human nature and the realities of power, where virtue alone is insufficient to navigate the complexities of leadership. By advocating for a realistic, results-oriented political strategy, he challenged the idealistic notions of his time, emphasizing that success in politics demands a willingness to act decisively, regardless of conventional ethical constraints. This perspective, though controversial, laid the groundwork for modern political realism and continues to spark debate about the role of morality in governance.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Separation of Morality and Politics | Machiavelli argued that political actions should be judged by their outcomes rather than moral principles. He believed that effective leadership often requires actions that might be considered unethical in personal life. |

| Realism Over Idealism | He emphasized practical, real-world considerations over idealistic or theoretical approaches to governance. Politics, according to Machiavelli, must be based on how things are, not how they should be. |

| Statecraft and Power | Machiavelli focused on the acquisition, maintenance, and exercise of power as the primary goals of politics. He viewed the state as an entity that must be preserved and strengthened, even at the expense of individual interests. |

| Human Nature as Self-Interested | He believed that people are inherently self-interested, ungrateful, and fickle. This view informed his advice to rulers to act decisively and pragmatically, rather than relying on the goodwill of others. |

| Effectiveness Over Virtue | Machiavelli prioritized the effectiveness of a ruler's actions over traditional virtues like honesty, compassion, or justice. A ruler, he argued, must be willing to use cunning, deceit, or force when necessary to achieve stability and security. |

| Adaptability and Flexibility | He stressed the importance of adaptability in politics, advising rulers to adjust their behavior according to circumstances. A successful leader must be both a "lion" (strong and fearless) and a "fox" (cunning and strategic). |

| Fear as a Tool | Machiavelli suggested that fear is a more reliable tool for maintaining control than love, as people are less likely to betray out of fear than out of love. However, he cautioned against being hated, as hatred can lead to rebellion. |

| Foundations of Political Order | He believed that a stable political order requires strong institutions, effective leadership, and a clear separation of political goals from moral or religious considerations. |

| Critique of Utopian Thinking | Machiavelli criticized utopian or idealistic political theories, arguing that they fail to account for the complexities and realities of human behavior and power dynamics. |

| Focus on Results | Ultimately, Machiavelli judged political actions by their results. Success in politics, for him, is measured by the ability to maintain power, secure the state, and achieve stability, regardless of the means used. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Human Nature: Machiavelli viewed humans as self-interested, requiring pragmatic leadership

- Power Dynamics: Politics must be separated to maintain control and stability

- Morality vs. Effectiveness: Political success often demands actions beyond ethical norms

- State Survival: Prioritizing the state's continuity over individual or moral considerations

- Realism in Governance: Idealism hinders practical decision-making in political leadership

Human Nature: Machiavelli viewed humans as self-interested, requiring pragmatic leadership

Niccolò Machiavelli's perspective on human nature is a cornerstone of his political philosophy, particularly in his seminal work, *The Prince*. Machiavelli viewed humans as fundamentally self-interested beings, driven by their own desires, ambitions, and survival instincts. This cynical yet pragmatic understanding of human nature led him to argue that effective leadership must be grounded in realism rather than idealism. He believed that people are inherently unpredictable and often act in ways that prioritize their personal gain over collective welfare. This view starkly contrasts with the moralistic and utopian perspectives of his predecessors, who often assumed that humans could be governed by virtue and reason alone.

Machiavelli's assertion that humans are self-interested has profound implications for his separation of politics from ethics. He argued that politics is a realm governed by necessity, not morality. Leaders, in his view, must operate within the constraints of human nature, which means they cannot afford to be bound by rigid moral principles. Instead, they must be willing to make difficult, often unpopular decisions to maintain order and power. This pragmatic approach requires leaders to be adaptable, calculating, and, at times, ruthless. Machiavelli famously stated that it is better for a ruler to be feared than loved if he cannot be both, as fear ensures stability in the face of human self-interest.

The separation of politics from ethics is further justified by Machiavelli's belief that human nature is unchanging and inherently flawed. He observed that people are quick to exploit kindness and slow to reciprocate goodwill. In such a world, a leader who governs with naivety or excessive virtue risks being overthrown or manipulated. Machiavelli’s advice to leaders is to act in accordance with the realities of human behavior, even if it means employing deceit, force, or manipulation. This does not imply that he endorsed immorality for its own sake, but rather that he recognized the necessity of such actions in securing and maintaining power in a self-interested world.

Pragmatic leadership, as Machiavelli conceived it, involves understanding and leveraging human nature to achieve political stability. He emphasized the importance of *virtù*, a term he used to describe a leader’s ability to act decisively and effectively, regardless of moral constraints. *Virtù* requires a leader to be proactive, foresighted, and willing to take bold actions to secure the state’s interests. For instance, Machiavelli praised leaders who could anticipate threats and neutralize them before they materialized, even if it meant acting preemptively against potential adversaries. This approach reflects his belief that the survival of the state is the highest priority, superseding individual moral considerations.

Finally, Machiavelli’s separation of politics from ethics is rooted in his conviction that the political realm is inherently chaotic and competitive. In such an environment, leaders must be prepared to navigate the complexities of human self-interest without being constrained by idealistic notions of justice or fairness. His philosophy challenges the traditional view that politics should be guided by moral principles, arguing instead that effective governance requires a clear-eyed understanding of human nature. By embracing pragmatism, leaders can ensure the longevity and stability of their rule, even if it means making choices that appear morally ambiguous. Machiavelli’s ideas remain influential because they offer a realistic, if unsettling, perspective on the nature of power and leadership in a world driven by self-interest.

Unveiling the Author: Who Wrote 'Politics and Administration'?

You may want to see also

Power Dynamics: Politics must be separated to maintain control and stability

Niccolò Machiavelli, in his seminal work *The Prince*, argues that politics must be separated from other spheres of human activity, particularly ethics and morality, to maintain control and stability in governance. This separation is rooted in his understanding of power dynamics, where the effective exercise of authority requires a pragmatic, often ruthless, approach. Machiavelli believed that leaders who conflate political decision-making with moral considerations risk weakening their power and inviting chaos. By isolating politics as a distinct realm, rulers can focus on the practicalities of maintaining order, securing their position, and ensuring the stability of the state.

The core of Machiavelli’s argument lies in the recognition that human nature is inherently self-interested and unpredictable. In such a world, a ruler cannot afford to be bound by moral constraints when making political decisions. Separating politics from ethics allows leaders to act decisively, even if their actions are perceived as harsh or unjust. For instance, Machiavelli suggests that a ruler must be willing to use force or deception when necessary to eliminate threats and consolidate power. This separation ensures that the ruler’s primary objective—the preservation of the state—remains unencumbered by sentimental or ethical dilemmas, thereby fostering stability.

Furthermore, Machiavelli emphasizes the importance of appearances versus reality in political power dynamics. A ruler must project an image of strength and virtue while being prepared to act in ways that may contradict this image behind the scenes. By separating politics from morality, leaders can navigate this duality effectively. For example, a ruler may need to break promises or employ cunning to outmaneuver rivals, actions that would be condemned in a moral framework but are justified in the political sphere for the greater good of stability. This strategic separation enables rulers to maintain control by adapting to the ever-changing dynamics of power.

Another critical aspect of Machiavelli’s reasoning is the need to manage fear and loyalty. He argues that it is better for a ruler to be feared than loved, as fear is a more reliable tool for maintaining control. However, this fear must be balanced with a degree of respect and order to avoid rebellion. By separating politics from emotional or moral considerations, rulers can make calculated decisions about when to use force, when to show mercy, and how to distribute rewards and punishments. This calculated approach ensures that power remains centralized and that the state remains stable, even in the face of internal and external challenges.

Finally, Machiavelli’s separation of politics serves as a safeguard against idealism and weakness in leadership. He critiques rulers who prioritize moral integrity over practical effectiveness, arguing that such leaders are ill-equipped to handle the complexities of governance. In Machiavelli’s view, politics is a realm of necessity, not choice, and leaders must be willing to do whatever is required to secure their power and protect the state. By embracing this separation, rulers can avoid the pitfalls of idealism and focus on the hard realities of power dynamics, ensuring long-term control and stability.

In conclusion, Machiavelli’s advocacy for separating politics is deeply tied to his understanding of power dynamics and the pragmatic demands of leadership. This separation allows rulers to act decisively, manage fear and loyalty, navigate the tension between appearance and reality, and avoid the weaknesses of moral idealism. By isolating politics as a distinct sphere, leaders can maintain control and stability in an unpredictable and often hostile world, fulfilling their primary duty to preserve the state.

Beyond Bipartisanship: Can America Embrace Multi-Party Politics?

You may want to see also

Morality vs. Effectiveness: Political success often demands actions beyond ethical norms

Niccolò Machiavelli, in his seminal work *The Prince*, presents a pragmatic view of politics that often challenges conventional moral principles. Central to his argument is the idea that political success frequently requires actions that transcend, or even contradict, ethical norms. Machiavelli separates politics from morality not to advocate immorality, but to emphasize the harsh realities of governance and statecraft. He posits that rulers must prioritize the stability and security of the state above personal virtue or moral scruples. This perspective arises from his observation that political environments are inherently unpredictable and often hostile, demanding leaders to act decisively, even if it means employing deceit, coercion, or force.

The tension between morality and effectiveness lies at the heart of Machiavelli’s philosophy. He argues that while virtuous behavior is admirable in private life, it can be detrimental in politics. For instance, a ruler who adheres strictly to honesty and fairness may find themselves outmaneuvered by adversaries who are willing to use cunning and manipulation. Machiavelli’s famous assertion that it is better for a prince to be feared than loved illustrates this point. Fear, he claims, ensures loyalty and order, whereas love is fickle and can lead to rebellion in times of crisis. Thus, effectiveness in maintaining power often necessitates actions that moral philosophy might condemn, such as breaking promises or using harsh measures to suppress dissent.

Machiavelli’s separation of politics from ethics is rooted in his realist understanding of human nature. He believes that people are inherently self-interested and unreliable, making it impractical for leaders to govern based on idealistic moral principles. Instead, rulers must be willing to adapt their behavior to the circumstances, even if it means acting immorally. For example, while lying is generally considered unethical, Machiavelli argues that a ruler may need to deceive to protect the state or achieve a greater good. This pragmatic approach prioritizes outcomes over intentions, suggesting that the success of a political action should be judged by its results rather than its adherence to moral standards.

Critics of Machiavelli often accuse him of promoting cynicism and immorality in politics. However, his argument is more nuanced. He does not advocate for arbitrary cruelty or corruption but rather for a calculated approach to governance. Machiavelli’s ideal prince is not a tyrant but a leader who understands when and how to use morally questionable tactics to secure the common good. For instance, while cruelty is generally reprehensible, Machiavelli argues that it can be justified if it is used swiftly and decisively to establish order and prevent greater suffering in the long run. This distinction highlights his belief that morality must sometimes be subordinated to effectiveness in the pursuit of political stability.

In conclusion, Machiavelli’s separation of politics from morality reflects his belief that political success often demands actions that go beyond ethical norms. His focus on effectiveness over virtue is not a call for immorality but a recognition of the complex and often unforgiving nature of political reality. By prioritizing the survival and prosperity of the state, Machiavelli challenges traditional moral frameworks, urging leaders to make difficult choices that may appear unethical but are necessary for achieving greater stability and security. This pragmatic approach remains a subject of debate, but it continues to offer valuable insights into the challenges of leadership and governance.

Who Pens New Politics Songs? Unveiling the Creative Minds Behind the Music

You may want to see also

Explore related products

State Survival: Prioritizing the state's continuity over individual or moral considerations

Niccolò Machiavelli, in his seminal work *The Prince*, argues that the survival and stability of the state must take precedence over individual interests or moral considerations. This perspective is rooted in his pragmatic approach to politics, where the primary goal of a ruler is to maintain power and ensure the continuity of the state, even if it means making difficult or morally ambiguous decisions. Machiavelli separates politics from ethics, asserting that the rules governing political action are distinct from those of personal morality. This separation is essential for effective governance, as it allows rulers to act decisively in the face of threats without being constrained by conventional moral standards.

State survival, according to Machiavelli, demands a focus on practical outcomes rather than idealistic principles. A ruler must be willing to prioritize the greater good of the state, even if it requires sacrificing individual rights or adhering to strict moral codes. For instance, during times of crisis, a ruler might need to employ harsh measures, such as suppressing dissent or engaging in deception, to protect the state from internal or external threats. Machiavelli famously states that it is better for a ruler to be feared than loved if it ensures stability, as love is unreliable in times of adversity, while fear can deter challenges to authority. This perspective underscores the idea that the state’s survival justifies actions that might otherwise be deemed unethical.

The continuity of the state also requires rulers to be adaptable and willing to act in ways that may appear contradictory or opportunistic. Machiavelli emphasizes the importance of *virtù*, a quality that combines skill, strength, and pragmatism, enabling rulers to respond effectively to changing circumstances. This adaptability often involves making tough choices that may alienate individuals or groups but are necessary for the state’s long-term survival. For example, alliances may be formed or broken based on expediency rather than loyalty, and promises may be reneged upon if they no longer serve the state’s interests. Such actions, while morally questionable, are justified if they secure the state’s stability.

Machiavelli’s separation of politics from morality is further illustrated in his distinction between how things ought to be and how they actually are. He argues that rulers must operate in the real world, where human nature is often selfish and unpredictable, rather than in an idealized realm governed by moral principles. This realism compels rulers to act in ways that may seem ruthless but are necessary to navigate the complexities of political power. For instance, while honesty and integrity are admirable traits in individuals, they can be liabilities for rulers who must sometimes employ deceit or force to maintain control and protect the state.

Ultimately, the principle of prioritizing state survival over individual or moral considerations reflects Machiavelli’s belief that the state is the highest political entity, and its preservation is the ultimate goal of governance. This perspective does not advocate for tyranny or injustice for its own sake but rather recognizes that difficult choices are often required to safeguard the collective well-being. Machiavelli’s approach remains controversial, but it offers a clear framework for understanding why political leaders must sometimes act in ways that seem morally questionable. In his view, the survival of the state is the cornerstone of political order, and all other considerations must be secondary to this imperative.

Are Political Party Attacks Legally Classified as Hate Crimes?

You may want to see also

Realism in Governance: Idealism hinders practical decision-making in political leadership

Niccolò Machiavelli, in his seminal work *The Prince*, separates politics from ethics, arguing that effective governance requires a pragmatic, realistic approach rather than idealistic principles. This distinction is rooted in the belief that idealism often hinders practical decision-making in political leadership. Realism in governance, as Machiavelli advocates, prioritizes the preservation of stability, power, and the state's interests over abstract moral ideals. By focusing on the realities of human nature and the complexities of political power, leaders can make decisions that are both effective and sustainable.

Idealism in politics, while noble in intention, often fails to account for the harsh realities of governance. Idealistic leaders may pursue policies based on moral purity or utopian visions, but these approaches frequently overlook the practical constraints of resources, human behavior, and geopolitical dynamics. For instance, a leader committed to absolute transparency or universal equality may find their goals undermined by the realities of corruption, resistance from vested interests, or the limitations of institutional capacity. Realism, on the other hand, acknowledges these challenges and seeks solutions that are feasible within existing conditions, even if they require difficult trade-offs.

Machiavelli’s separation of politics from ethics is not an endorsement of immorality but a recognition that political leadership demands a different moral calculus. In a world where threats are constant and resources are finite, leaders must sometimes make unpopular or seemingly amoral decisions to secure the greater good. For example, a realist leader might prioritize national security over short-term economic gains or engage in strategic alliances with unsavory regimes to achieve long-term stability. Idealism, in such scenarios, can lead to paralysis or counterproductive outcomes, as it often prioritizes moral purity over practical efficacy.

Moreover, idealism tends to underestimate the role of power in politics. Machiavelli argues that power is the currency of governance, and its effective use is essential for maintaining order and achieving goals. Idealistic leaders, however, may shy away from exercising power decisively, fearing it will tarnish their moral image. This reluctance can lead to weak governance, as adversaries exploit indecision and the state loses its ability to enforce laws or protect its citizens. Realism, by contrast, embraces the necessity of power and encourages leaders to use it judiciously to secure the state’s interests.

Finally, realism in governance fosters adaptability, a critical trait in an ever-changing political landscape. Idealistic approaches often rigidly adhere to fixed principles, leaving little room for maneuver when circumstances shift. Realist leaders, however, are willing to adjust their strategies based on evolving realities, ensuring that their decisions remain relevant and effective. This flexibility is particularly important in crisis situations, where quick, pragmatic responses can mean the difference between stability and chaos. By embracing realism, political leaders can navigate complexity with clarity and purpose, avoiding the pitfalls of idealism that often lead to impractical or counterproductive outcomes.

In conclusion, Machiavelli’s separation of politics from ethics underscores the importance of realism in governance. Idealism, while inspiring, hinders practical decision-making by ignoring the realities of power, human nature, and resource constraints. Realism, on the other hand, equips leaders with the tools to make tough, effective decisions that prioritize the state’s survival and prosperity. In a world fraught with uncertainty, the pragmatic approach advocated by Machiavelli remains a timeless guide for political leadership.

Mastering Polite Phone Etiquette: Why Courtesy Matters in Every Call

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Machiavelli separated politics from ethics to focus on the practical realities of power and governance. He argued that effective leadership often requires actions that may not align with traditional moral principles but are necessary for maintaining stability and achieving political goals.

Machiavelli justified this separation by emphasizing the unpredictable and often harsh nature of political life. He believed that rulers must prioritize the survival and success of the state, even if it means employing deceit, force, or other morally questionable tactics.

Machiavelli’s approach revolutionized political theory by introducing a pragmatic, results-oriented perspective. It challenged the prevailing view that politics should be guided by moral or religious principles, laying the groundwork for modern political realism and the study of power dynamics.