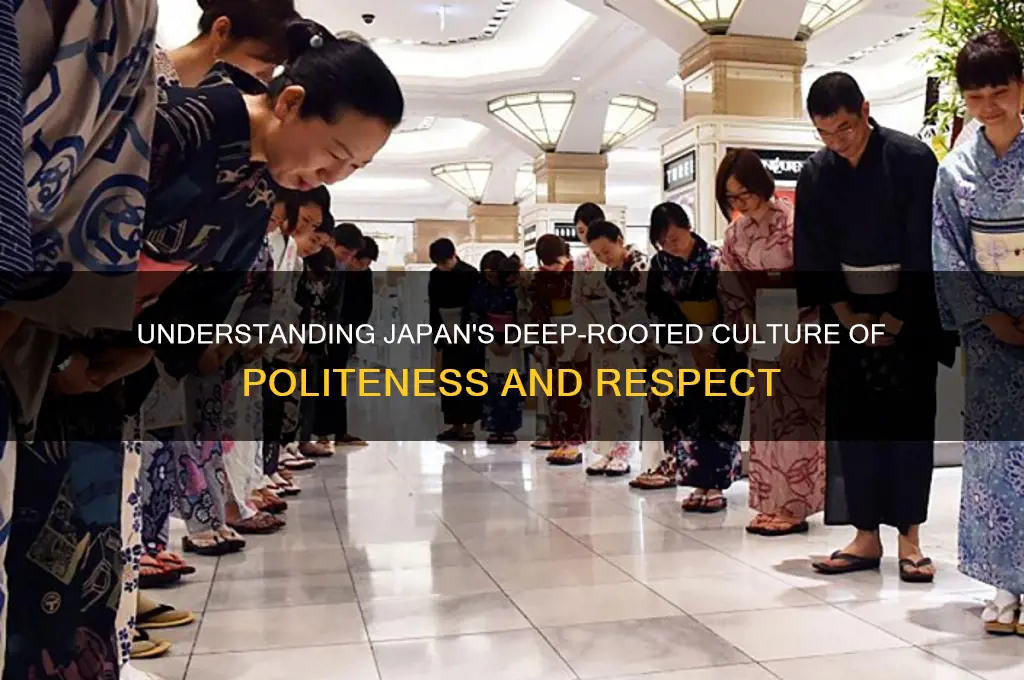

Japanese culture is renowned for its emphasis on politeness, deeply rooted in principles such as *wa* (harmony) and *omoiyari* (consideration for others), which prioritize collective well-being over individual desires. From a young age, Japanese people are taught to value respect, humility, and social etiquette, as reflected in practices like bowing, using honorific language, and adhering to strict social norms. The influence of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Shintoism has instilled a sense of duty and mindfulness in interpersonal interactions, while the societal importance of *tatemae* (public facade) encourages maintaining a polite and harmonious appearance. Additionally, Japan’s densely populated environment has fostered a culture of mutual respect and self-discipline to ensure smooth coexistence, making politeness not just a personal virtue but a societal necessity.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Collectivist Culture | Emphasis on group harmony and interdependence, prioritizing community needs over individual desires. |

| Confucian Influence | Strong respect for hierarchy, elders, and authority figures, rooted in Confucian principles. |

| Education & Socialization | Rigorous education system and societal norms that instill manners, respect, and self-discipline from a young age. |

| Indirect Communication | Preference for indirect, nuanced communication to avoid conflict and maintain harmony. |

| Honorific Language | Use of honorifics (keigo) to show respect based on social status and relationships. |

| Face-Saving (Mento-mochi) | Importance of preserving one’s dignity and avoiding embarrassment in social interactions. |

| Attention to Detail | Meticulousness in daily tasks, from customer service to personal presentation, reflecting respect and care. |

| Public Etiquette | Strict adherence to public manners, such as cleanliness, quietness, and orderly behavior. |

| Gratitude & Apology Culture | Frequent expressions of gratitude (arigatou) and apologies (sumimasen) to acknowledge others and rectify mistakes. |

| Work Ethic & Dedication | Strong sense of duty (giri) and commitment to excellence in professional and personal responsibilities. |

| Religious & Philosophical Roots | Influence of Shinto and Buddhism, emphasizing humility, mindfulness, and respect for all beings. |

| Social Pressure & Conformity | High value placed on fitting in and adhering to societal norms to avoid disapproval. |

| Customer Service Excellence | Omotenashi (hospitality) culture, prioritizing customer satisfaction and anticipating needs. |

| Modesty & Humility | Avoidance of boasting and emphasis on self-effacement, reflecting cultural values of humility. |

| Respect for Privacy | Valuing personal space and avoiding intrusive behavior in public and private settings. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Cultural Values: Politeness rooted in harmony, respect, and collectivism, prioritizing group well-being over individual desires

- Language Structure: Honorifics and formal speech levels enforce social hierarchy and respectful communication

- Education System: Schools emphasize manners, discipline, and social etiquette from a young age

- Religious Influence: Shinto and Buddhism teach humility, gratitude, and mindfulness in daily interactions

- Social Pressure: Strong societal expectations and fear of shame drive adherence to polite behavior

Cultural Values: Politeness rooted in harmony, respect, and collectivism, prioritizing group well-being over individual desires

Japanese politeness is deeply rooted in cultural values that prioritize harmony, respect, and collectivism, fostering a society where the well-being of the group is often placed above individual desires. This ethos is reflected in the concept of *wa* (和), which emphasizes harmony and the smooth functioning of social relationships. In Japan, maintaining *wa* is paramount, and politeness serves as a tool to avoid conflict and ensure that interactions are respectful and considerate. For instance, the use of honorific language (*keigo*) in Japanese communication is not merely a linguistic formality but a way to acknowledge social hierarchies and show deference to others, thereby preserving harmony.

Respect is another cornerstone of Japanese culture, deeply ingrained from childhood. The value of *sonkei* (尊重), or respect, is taught through practices such as bowing, using polite titles, and prioritizing the needs of others. This respect extends beyond individuals to institutions, traditions, and even objects, as seen in the careful handling of items like business cards or the meticulous presentation of food. Such behaviors reinforce the idea that every action has an impact on others and should be performed with consideration and care, aligning with the collective good.

Collectivism plays a central role in shaping Japanese politeness, as the culture emphasizes the interdependence of individuals within a group. Unlike individualistic societies, where personal goals and achievements are often celebrated, Japan values the cohesion and success of the collective. This is evident in the workplace, where employees prioritize team goals over personal ambitions and in social settings, where individuals often suppress their own desires to avoid causing inconvenience to others. Politeness, in this context, is a means of ensuring that one’s actions contribute positively to the group rather than disrupting it.

The prioritization of group well-being over individual desires is further exemplified in everyday behaviors, such as the practice of *nemawashi* (根回し), a consensus-building process that ensures all parties are consulted before a decision is made. This approach minimizes conflict and ensures that everyone feels valued and included, even if it means prolonging the decision-making process. Similarly, the Japanese tendency to avoid direct confrontation and instead use indirect communication is a way to protect the feelings of others and maintain group harmony, even at the expense of personal expression.

These cultural values are reinforced through education, social norms, and traditions, creating a society where politeness is not just a behavior but a way of life. From the early years, children are taught to consider the impact of their actions on others, whether it’s sharing toys in kindergarten or cleaning their classrooms as a group. This emphasis on collective responsibility and mutual respect ensures that politeness becomes second nature, deeply embedded in the Japanese identity. Ultimately, the politeness observed in Japanese culture is a reflection of its core values, where harmony, respect, and collectivism are not just ideals but guiding principles that shape every interaction.

Can SBA Funds Legally Support Political Parties? Key Insights Revealed

You may want to see also

Language Structure: Honorifics and formal speech levels enforce social hierarchy and respectful communication

The Japanese language is inherently structured to reflect and reinforce social hierarchy and respect, primarily through the use of honorifics and formal speech levels. Unlike English, where politeness is often conveyed through tone or specific phrases, Japanese grammar itself mandates respectful expression based on the speaker’s relationship with the listener. Honorifics, known as *keigo*, are specialized linguistic forms that elevate the status of the person being spoken to or about. For example, verbs and nouns change to more polite forms, such as *tabemasu* (to eat, polite) instead of *taberu* (to eat, casual). This grammatical structure ensures that respect is not optional but embedded in the language, making it a fundamental aspect of daily communication.

Formal speech levels in Japanese further enforce social hierarchy by clearly distinguishing between superiors, equals, and inferiors. There are three primary levels: *teineigo* (polite), *sonkeigo* (respectful), and *kenjougo* (humble). *Teineigo* is the standard polite form used in most interactions, while *sonkeigo* elevates the listener’s actions (e.g., *o-ki ni iraremasu ka?* for "do you like it?"), and *kenjougo* lowers the speaker’s actions (e.g., *go-shushin sareta* for "I returned"). These levels are not interchangeable; using the wrong form can be seen as disrespectful or overly familiar. This precision in language compels speakers to be constantly aware of their social position relative to others, fostering a culture of mindfulness and respect.

The use of honorifics and formal speech levels is deeply tied to Japan’s collectivist culture, where maintaining harmony (*wa*) in relationships is paramount. By employing these linguistic tools, individuals acknowledge the social roles and statuses of those around them, reducing the likelihood of conflict or misunderstanding. For instance, a subordinate at work would use *kenjougo* when speaking to a superior, emphasizing their humility and respect for the hierarchy. This practice extends beyond professional settings into everyday life, such as when addressing elders, customers, or strangers. The language structure thus acts as a social lubricant, ensuring interactions remain courteous and orderly.

Moreover, the complexity of *keigo* requires deliberate effort to master, which itself reflects a commitment to respect. Children are taught from a young age to use appropriate forms, and adults often undergo training to refine their *keigo* skills, especially in customer service or corporate environments. This emphasis on linguistic precision underscores the cultural value placed on politeness and social harmony. The very act of learning and using these forms cultivates a mindset of consideration for others, as speakers must constantly adapt their language to suit the context and the listener’s status.

In summary, the Japanese language’s structure of honorifics and formal speech levels is a powerful mechanism for enforcing social hierarchy and promoting respectful communication. By embedding respect into grammar and vocabulary, Japanese culture ensures that politeness is not merely a choice but a linguistic obligation. This system not only reflects societal values but also actively shapes behavior, contributing to the widespread perception of Japanese people as inherently polite. Through language, Japan maintains a delicate balance of hierarchy and harmony, making respect an integral part of its cultural identity.

Are Political Party Committees Truly Organized for Effective Governance?

You may want to see also

Education System: Schools emphasize manners, discipline, and social etiquette from a young age

The Japanese education system plays a pivotal role in instilling politeness and social etiquette from a very young age. Unlike many Western systems, Japanese schools integrate the teaching of manners and discipline into their daily routines, ensuring that students not only learn academic subjects but also develop strong social skills. From the moment children enter kindergarten, they are taught the importance of greeting others, bowing, and using polite language. These practices are reinforced through repetitive exercises and role-playing activities, making them second nature to the students. This early emphasis on etiquette lays the foundation for the polite behavior that is so characteristic of Japanese society.

Discipline is another cornerstone of the Japanese education system, closely tied to the cultivation of politeness. Schools enforce strict rules regarding punctuality, cleanliness, and respect for authority, which students are expected to follow without question. For instance, students are often responsible for cleaning their classrooms and school premises, a practice known as *souji*. This not only fosters a sense of responsibility but also teaches them to value the collective good over individual convenience. Such disciplined environments encourage students to internalize the importance of adhering to social norms, which in turn promotes polite and considerate behavior.

Social etiquette is further emphasized through structured interactions and group activities. Japanese schools often organize students into small groups or teams, where they learn to cooperate, communicate, and resolve conflicts politely. Teachers act as role models, demonstrating respectful behavior and addressing students with honorific language. This creates a culture where politeness is not just expected but also celebrated. Additionally, schools frequently hold events like *undokai* (sports day) and *bunka-sai* (cultural festivals), where students practice formal greetings, expressions of gratitude, and teamwork, reinforcing their understanding of social norms.

The curriculum itself also incorporates lessons on traditional values and moral education, known as *tokkatsu* (special activities). These lessons focus on virtues such as humility, empathy, and selflessness, which are essential components of polite behavior. Students are taught to consider the feelings and needs of others, a principle deeply rooted in Japanese culture. For example, phrases like *sumimasen* (excuse me) and *arigatou gozaimasu* (thank you very much) are drilled into their vocabulary, ensuring they become habitual in daily interactions. This formal and respectful language is not just a matter of etiquette but a reflection of the societal emphasis on harmony and mutual respect.

Finally, the education system’s focus on manners, discipline, and social etiquette extends beyond the classroom, influencing students’ behavior in their communities. Parents and teachers often collaborate to reinforce these values at home, creating a cohesive environment where politeness is consistently encouraged. This holistic approach ensures that the lessons learned in school are applied in real-life situations, from public transportation to interpersonal relationships. As a result, the Japanese education system not only produces academically proficient individuals but also cultivates a society where politeness and consideration are deeply ingrained in everyday life.

Are Democrats and Republicans Truly Different? Examining Political Party Similarities

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Religious Influence: Shinto and Buddhism teach humility, gratitude, and mindfulness in daily interactions

The deep-rooted politeness in Japanese culture can be significantly attributed to the religious influence of Shinto and Buddhism, which have shaped societal values over centuries. Shinto, Japan’s indigenous religion, emphasizes harmony with nature and the community. It teaches that every action has a spiritual consequence, fostering a sense of mindfulness in daily interactions. Shinto rituals often involve expressions of gratitude, such as bowing and offering thanks to kami (spirits or deities), which instills a habit of appreciation and respect in adherents. This religious practice translates into everyday life, where politeness is seen as a way to maintain balance and harmony in relationships.

Buddhism, introduced to Japan in the 6th century, complements Shinto by emphasizing humility and compassion. The Buddhist concept of *anatta* (no-self) teaches that the ego is an illusion, encouraging individuals to act selflessly and consider others before themselves. This principle is reflected in Japanese etiquette, where prioritizing the comfort and dignity of others is paramount. For example, phrases like *sumimasen* (excuse me) and *arigatou* (thank you) are deeply ingrained in daily speech, demonstrating a constant awareness of one’s impact on others. Buddhism’s focus on mindfulness also encourages individuals to be fully present in their interactions, ensuring that every gesture, word, and action is thoughtful and respectful.

The synergy between Shinto and Buddhism in Japan creates a cultural framework where humility, gratitude, and mindfulness are not just virtues but essential practices. Shinto’s emphasis on gratitude toward the environment and community aligns with Buddhism’s teachings on selflessness and compassion, fostering a society where politeness is a natural expression of these values. For instance, the Japanese custom of bowing is both a Shinto expression of respect for the divine and a Buddhist acknowledgment of the equality and worth of every individual. This dual religious influence ensures that politeness is not merely a social norm but a spiritual discipline.

In daily life, these religious teachings manifest in the meticulous attention to detail and consideration for others that Japanese people are known for. Whether it’s the careful wrapping of gifts, the precise language used in formal settings, or the quiet demeanor in public spaces, these behaviors reflect a mindfulness rooted in Shinto and Buddhist principles. The act of apologizing, even for minor inconveniences, is a direct expression of humility and awareness of one’s role in the larger community, as taught by both religions. This religious foundation elevates politeness from a superficial courtesy to a profound cultural ethic.

Ultimately, the politeness of the Japanese people is a living testament to the enduring influence of Shinto and Buddhism. These religions provide a moral and spiritual framework that encourages individuals to approach every interaction with humility, gratitude, and mindfulness. By internalizing these teachings, the Japanese have cultivated a society where politeness is not just expected but is a reflection of deeper spiritual values. This religious influence ensures that respect and consideration for others remain at the heart of Japanese culture, making it a hallmark of their identity.

UK Political Parties: Climate Change Commitment or Empty Promises?

You may want to see also

Social Pressure: Strong societal expectations and fear of shame drive adherence to polite behavior

In Japanese society, social pressure plays a pivotal role in shaping the behavior of individuals, particularly in fostering a culture of politeness. From a young age, Japanese people are taught the importance of maintaining harmony within their communities. This emphasis on group cohesion creates a strong sense of societal expectation, where being polite is not just a personal choice but a collective responsibility. The concept of *wa* (和), or harmony, is deeply ingrained in Japanese culture, and deviating from polite norms is often seen as disruptive to this balance. As a result, individuals feel a constant, unspoken pressure to conform to these standards, ensuring they do not become a source of discord.

The fear of shame, or *haji* (恥), is another powerful motivator for polite behavior in Japan. Public embarrassment is highly avoided, as it not only reflects poorly on the individual but also on their family, workplace, or social circle. This fear is reinforced through various social mechanisms, such as indirect criticism or the silent disapproval of others. For example, failing to bow properly, using overly casual language in formal settings, or neglecting to apologize when necessary can lead to subtle but effective social consequences. Over time, this fear becomes internalized, driving individuals to adhere strictly to polite norms to avoid becoming a target of shame.

Education and upbringing further amplify the impact of social pressure on politeness. Japanese children are taught specific manners and etiquette from a very early age, often through repetition and reinforcement at home, school, and in public spaces. Phrases like *arigatou* (thank you) and *sumimasen* (excuse me) become second nature, as do gestures like bowing and giving and receiving gifts with both hands. These practices are not just taught as optional behaviors but as essential components of being a respectful and accepted member of society. The constant reinforcement of these norms ensures that politeness becomes a habitual and almost instinctive response.

Workplace culture in Japan also exemplifies how social pressure drives polite behavior. Employees are expected to prioritize the group’s success over individual achievements, and politeness is seen as a key tool for maintaining workplace harmony. This includes using honorific language (*keigo*) when speaking to superiors, showing deference through body language, and avoiding confrontations that could create tension. Those who fail to adhere to these norms risk being labeled as *mayaku* (troublesome) or *jiko-chu* (self-centered), which can hinder career advancement and social acceptance. Thus, the fear of professional and social repercussions keeps individuals aligned with polite standards.

Finally, media and public discourse in Japan often reinforce the importance of politeness, further embedding it into the national psyche. Television shows, advertisements, and public service announcements frequently highlight the virtues of being considerate and respectful. Stories of individuals who go out of their way to help others or maintain composure in difficult situations are celebrated, while examples of impoliteness are often portrayed negatively. This constant messaging from media outlets contributes to the societal expectation that politeness is not just a personal trait but a civic duty. Together, these factors create a powerful social pressure that ensures politeness remains a cornerstone of Japanese culture.

Can Political Parties Collaborate for a Unified and Effective Governance?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Japanese culture places a strong emphasis on harmony, respect, and social etiquette, rooted in Confucian principles and the concept of "wa" (和), which means peace and unity. Politeness is seen as essential to maintaining positive relationships and societal order.

The education system in Japan teaches children from a young age the importance of respect, humility, and consideration for others. Students are often trained in formal manners, such as bowing and using honorific language, which reinforces polite behavior.

While some aspects of Japanese politeness may seem formal or scripted, they are deeply ingrained in the culture and are generally genuine expressions of respect. However, like in any culture, individual attitudes may vary, and politeness can sometimes be a way to maintain social harmony rather than reflect personal feelings.

In Japan, preserving one’s "face" (reputation or dignity) and avoiding causing embarrassment to others is crucial. Politeness, such as using indirect language and avoiding confrontation, helps maintain harmony and respect for others' "face," which is highly valued in Japanese society.