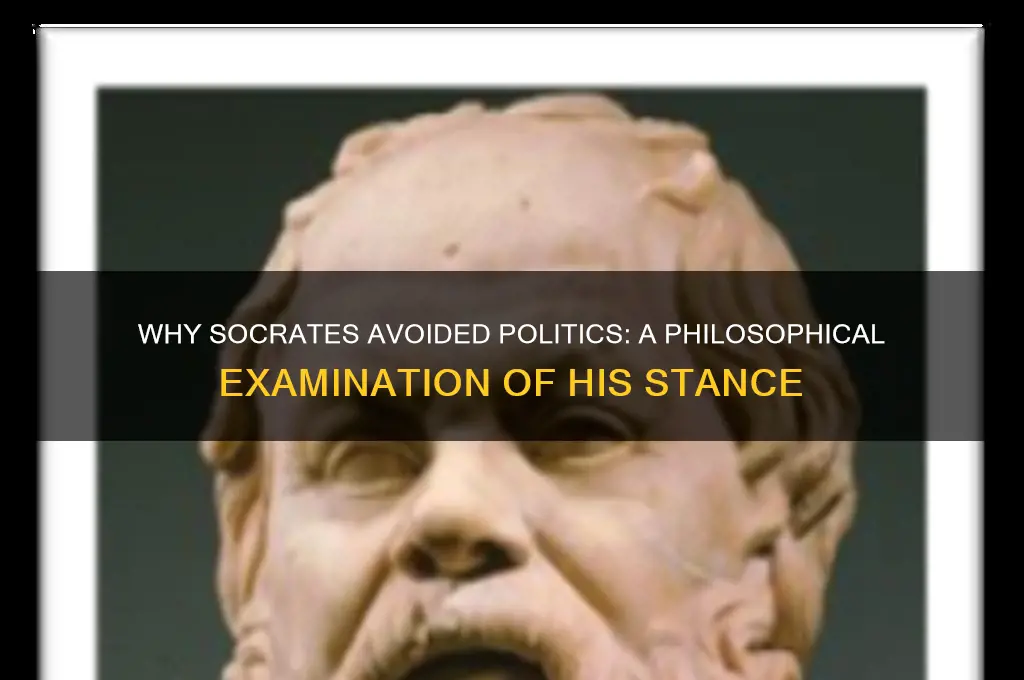

Socrates' apparent lack of political engagement has long puzzled scholars, given his profound influence on Western philosophy and his Athenian citizenship during a tumultuous period in the city-state's history. Despite living through critical events such as the Peloponnesian War and the oligarchic regime of the Thirty Tyrants, Socrates remained notably absent from active political roles or public office. This seeming detachment raises questions about his priorities, beliefs, and the nature of his philosophical mission. While some argue that his focus on ethical inquiry and the pursuit of truth rendered politics secondary, others suggest that his method of questioning authority and challenging conventional wisdom was, in itself, a form of political engagement. Understanding why Socrates chose not to participate in traditional politics requires examining his philosophical commitments, his views on justice, and the broader context of Athenian democracy.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Focus on Individual Virtue | Socrates believed true change came from improving individual morality, not political systems. He prioritized philosophical inquiry and self-examination over direct political involvement. |

| Criticism of Athenian Democracy | He was skeptical of the competence of the average citizen to make sound political decisions, often criticizing the Athenian democratic process as being influenced by rhetoric and emotion rather than reason. |

| Commitment to Truth and Justice | Socrates saw his role as a "gadfly" to the state, questioning authority and challenging conventional wisdom. He believed his pursuit of truth and justice was more important than aligning with any political faction. |

| Method of Questioning (Elenchus) | His method of questioning, aimed at exposing ignorance and encouraging critical thinking, often led to conflict with powerful figures, making political engagement risky. |

| Disdain for Power and Prestige | Socrates showed little interest in wealth, status, or political power, valuing wisdom and virtue above all else. |

| Belief in Divine Mission | He claimed to be guided by a divine voice (his "daimonion"), which directed him towards his philosophical mission rather than political pursuits. |

| Acceptance of Fate | Socrates accepted his sentence of death calmly, believing it was his fate and that true wisdom lay in accepting the will of the gods. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Socrates' focus on individual virtue over political engagement

Socrates' apparent lack of political engagement, as depicted in Plato's dialogues, stems from his profound focus on individual virtue and self-examination. For Socrates, the pursuit of wisdom and moral excellence was the highest calling, and he believed that true political improvement could only arise from the ethical transformation of individuals. This perspective led him to prioritize philosophical inquiry over direct involvement in Athenian politics. Socrates argued that before one could contribute meaningfully to the state, one must first understand justice, courage, and piety within oneself. His famous dictum, "know thyself," encapsulates this inward focus, suggesting that self-knowledge is the foundation for any external action, including political participation.

Socrates' method of questioning, known as the Socratic method, further underscores his emphasis on individual virtue. By engaging in dialogues that exposed the ignorance and contradictions of his interlocutors, Socrates sought to help individuals recognize their own moral deficiencies. He believed that political corruption was a symptom of personal ethical failings, and thus, addressing these failings was more critical than engaging in political debates or holding office. For Socrates, the unexamined life was not worth living, and this examination was a deeply personal and philosophical endeavor rather than a political one. His focus on individual virtue was, therefore, a prerequisite for any meaningful societal change.

Another reason for Socrates' limited political activity was his skepticism about the competence of Athenian democracy. He often criticized the idea that political power should be wielded by those who were merely popular or persuasive rather than those who were truly wise. In the *Apology*, Socrates recounts how the oracle at Delphi declared him the wisest man because he alone recognized his own ignorance. This humility and commitment to truth contrasted sharply with the arrogance and self-assurance of many Athenian politicians. Socrates believed that true leadership required moral integrity and wisdom, qualities he saw as lacking in the political sphere. Thus, he chose to focus on cultivating these qualities in individuals rather than participating in a system he deemed flawed.

Furthermore, Socrates' philosophical mission was inherently at odds with the demands of political life. Political engagement often requires compromise, strategic alliances, and adherence to public opinion, whereas Socrates' pursuit of truth and virtue was uncompromising and unconcerned with popularity. His relentless questioning and criticism of Athenian leaders and institutions made him a controversial figure, ultimately leading to his trial and execution. By remaining politically inactive, Socrates preserved his integrity and continued his philosophical work without being entangled in the power struggles of the state. His focus on individual virtue was not a retreat from societal responsibility but a radical redefinition of it, emphasizing the importance of personal ethics over political ambition.

In conclusion, Socrates' focus on individual virtue over political engagement was rooted in his belief that ethical self-improvement was the cornerstone of a just society. His philosophical method, skepticism of Athenian democracy, and commitment to truth all contributed to his decision to prioritize personal ethics over political activity. While this choice ultimately led to his downfall, it also cemented his legacy as a thinker who challenged individuals to seek wisdom and virtue above all else. Socrates' approach remains a powerful reminder that true societal change begins with the transformation of the individual.

Mike Pence: The Political Dummy Behind the Scenes?

You may want to see also

His distrust of Athenian democracy and its leaders

Socrates' distrust of Athenian democracy and its leaders is a central theme in understanding his political passivity. He was deeply critical of the democratic system in Athens, not because he opposed the idea of democracy itself, but because he believed it was flawed in its execution. Athenian democracy, in Socrates' view, was ruled by the whims of the majority, who were often swayed by rhetoric and emotion rather than reason and wisdom. This system, he argued, prioritized popularity and persuasiveness over truth and justice, leading to decisions that were not in the best interest of the city-state. Socrates famously likened the Athenian democracy to a ship captained by a chaotic crew, where anyone who could shout the loudest could steer the vessel, regardless of their knowledge of navigation.

His skepticism of Athenian leaders further deepened his distrust. Socrates believed that political leaders in Athens were more concerned with personal gain and maintaining power than with the welfare of the citizens. He often pointed out the incompetence and moral corruption of many politicians, who lacked the philosophical understanding necessary to govern justly. In the *Apology*, Socrates recounts how he questioned prominent Athenians, only to discover that they did not possess the wisdom they claimed, despite their positions of authority. This experience reinforced his belief that the leaders of Athens were ill-equipped to guide the city, as they were more focused on rhetoric and public image than on genuine wisdom and virtue.

Socrates' encounters with Athenian politicians, such as his criticism of Pericles and his clash with the Thirty Tyrants, further solidified his distrust. He saw firsthand how power could corrupt and how leaders could misuse their authority to serve their own interests. For instance, during the rule of the Thirty Tyrants, a brutal oligarchy that briefly replaced the democracy, Socrates refused to comply with their unjust orders, demonstrating his commitment to moral integrity over political obedience. This incident highlighted his belief that Athenian leaders, whether democratic or oligarchic, were often driven by self-interest rather than the common good.

Another aspect of Socrates' distrust was his belief that true leadership required a deep understanding of ethics and justice, which he found lacking in Athenian politicians. He argued that ruling justly necessitated self-knowledge and a commitment to virtue, qualities he rarely observed in those who held power. In the *Republic*, Plato portrays Socrates as advocating for philosopher-kings—individuals who possess both wisdom and a love of truth—as the ideal rulers. By contrast, Athenian democracy elevated leaders who were skilled in rhetoric but lacked the philosophical insight needed to govern wisely. This disparity between Socrates' ideal of leadership and the reality of Athenian politics further alienated him from active participation.

Finally, Socrates' distrust of Athenian democracy and its leaders was rooted in his belief that the system encouraged moral relativism and the neglect of individual virtue. He argued that democracy's focus on majority rule often led to the suppression of dissenting voices and the erosion of moral standards. In his view, true justice could only be achieved through the cultivation of personal virtue and the pursuit of wisdom, not through the fluctuating opinions of the masses. This philosophical stance made it impossible for him to engage in a political system he saw as inherently flawed and morally compromised. Thus, his distrust of Athenian democracy and its leaders was not merely a political stance but a reflection of his deeper commitment to truth, justice, and the examined life.

Who Shapes Political Discourse on Twitter? A Demographic Analysis

You may want to see also

Philosophical priorities overshadowing civic participation

Socrates' apparent lack of political engagement has long been a subject of intrigue, especially considering the tumultuous political landscape of ancient Athens. One of the primary reasons often cited for his political inactivity is the overwhelming presence of philosophical priorities in his life. Socrates' singular focus on the pursuit of truth, self-examination, and the betterment of the soul through philosophical inquiry left little room for traditional civic participation. This philosophical dedication, while immensely valuable to Western thought, seemed to overshadow his involvement in the day-to-day political affairs of the city-state.

The Socratic method, a form of inquiry and debate, was his primary tool for exploring ethical concepts and the nature of justice. Engaging in this philosophical dialogue was not merely an intellectual exercise for Socrates; it was a moral imperative. He believed that the unexamined life was not worth living, and thus, his days were spent in the agora, questioning and discussing with fellow Athenians. This relentless pursuit of wisdom and virtue, while beneficial to individual moral development, diverted his attention from the practicalities of political activism. Socrates' philosophy was inherently tied to personal ethics, and he saw the improvement of the soul as a more urgent task than engaging in the often-corrupt world of Athenian politics.

In Plato's works, Socrates is portrayed as a critic of the Athenian democratic system, not out of disdain for democracy itself, but due to his belief that the citizens were not adequately prepared for self-governance. He argued that most people lacked the necessary wisdom and understanding of justice, which he considered essential for effective political participation. This perspective further highlights how his philosophical ideals created a barrier to conventional political involvement. Socrates' priority was to educate and guide individuals towards moral excellence, a task he deemed more crucial than direct political action.

Furthermore, Socrates' philosophical inquiries often led him to challenge the status quo and question the beliefs of powerful figures in Athens. His relentless pursuit of truth and justice, as depicted in Plato's dialogues, made him a controversial figure. This philosophical stance, while intellectually courageous, could have been a strategic choice to avoid the pitfalls of political life, where speaking truth to power might have had severe consequences. By focusing on philosophy, Socrates could influence society's moral compass without engaging in the potentially dangerous game of politics.

The idea that philosophical reflection and civic engagement are mutually exclusive is a complex one, especially in the context of ancient Greek society. Socrates' life demonstrates that the intense dedication required for philosophical pursuits can indeed overshadow political activities. His legacy suggests that sometimes, the greatest impact on society can come from challenging individuals to think critically and ethically, rather than through direct political involvement. This perspective raises important questions about the role of philosophers in society and the potential trade-offs between intellectual pursuits and civic duties.

Do Political Parties Receive Taxpayer Funding? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Belief in divine guidance limiting political action

Socrates' limited political engagement is often attributed to his profound belief in divine guidance, which played a pivotal role in shaping his actions and decisions. Central to this belief was his conviction that a divine voice, often referred to as his "daimonion," provided him with moral and ethical direction. This inner voice, which Socrates described as a supernatural sign, would warn him against certain actions but never actively encourage him to pursue specific endeavors. The daimonion's role was primarily inhibitory, acting as a safeguard against potential errors rather than a proactive guide toward political involvement. This reliance on divine signals inherently constrained Socrates' political activity, as he felt compelled to defer to this higher authority rather than act on his own judgment in public affairs.

The nature of Socrates' divine guidance was deeply personal and introspective, which further limited his political engagement. Unlike traditional political figures who sought external validation or public consensus, Socrates' moral compass was rooted in his internal dialogue with the divine. This inward focus made him skeptical of the conventional mechanisms of political power and decision-making, which he often viewed as corrupt or misguided. For instance, in Plato's *Apology*, Socrates explains that his divine mission was to question the wisdom of those in power, not to seek power himself. This self-imposed limitation reflected his belief that true wisdom came from acknowledging one's ignorance, a stance that was at odds with the assertive and often dogmatic nature of political leadership.

Socrates' belief in divine guidance also led him to prioritize philosophical inquiry over political action. He saw his role as a "midwife of the soul," helping individuals give birth to their own truths through dialogue and questioning. This philosophical mission, which he believed was divinely ordained, took precedence over any potential political ambitions. Socrates argued that the pursuit of virtue and wisdom was more critical than engaging in the practicalities of governance, which he deemed secondary to the moral development of the individual. By focusing on personal and collective enlightenment, Socrates effectively sidelined himself from active political participation, viewing it as a distraction from his higher calling.

Furthermore, Socrates' divine guidance instilled in him a sense of humility and caution, traits that discouraged political activism. He frequently expressed doubt about his own knowledge and abilities, emphasizing that true wisdom lay in recognizing the limits of human understanding. This humility extended to his views on political leadership, as he believed that those who sought power were often the least qualified to wield it. In his eyes, the divine had not called him to govern but to challenge the assumptions of those who did. This perspective reinforced his reluctance to engage in politics, as he felt that his role was to question authority rather than to become a part of it.

Finally, Socrates' belief in divine guidance aligned with his broader critique of Athenian democracy, which he saw as flawed and prone to mob rule. He argued that political decisions should be based on wisdom and virtue, not popular opinion, and that true leadership required a moral foundation that most politicians lacked. By adhering to his divine mission, Socrates positioned himself as a moral critic rather than a political actor, using his philosophical inquiries to expose the shortcomings of the political system. This stance, while influential, kept him on the periphery of political life, as he chose to remain a voice of conscience rather than a participant in the political arena. In essence, Socrates' belief in divine guidance was both a source of his moral authority and a fundamental reason for his limited political action.

George Washington's Dislike for Political Parties: A Founding Father's Warning

You may want to see also

Criticism of politics as corrupt and unworthy

Socrates' perceived lack of political engagement has often been attributed to his deep-rooted criticism of the political landscape of his time, which he viewed as inherently corrupt and unworthy of his participation. Central to his critique was the belief that Athenian politics was dominated by individuals who prioritized personal gain over the common good. In dialogues such as *Gorgias*, Socrates exposes the moral bankruptcy of rhetoricians and politicians who manipulate language to sway public opinion, often leading to unjust decisions. He argues that such figures lack genuine wisdom and virtue, rendering their leadership not only ineffective but harmful to the polis. This corruption, in Socrates' view, made political involvement a morally compromising endeavor.

Another aspect of Socrates' criticism lies in his disdain for the democratic process as practiced in Athens, which he saw as a system that elevated popularity and eloquence over truth and justice. In *The Apology*, he recounts how politicians and orators often convinced the Athenian assembly to act against its own best interests through persuasive but deceitful rhetoric. Socrates believed that true leadership required philosophical inquiry and a commitment to ethical principles, qualities he found absent in the political sphere. For him, engaging in such a system would mean participating in its flaws, which he considered unworthy of a philosopher's pursuit of truth and virtue.

Socrates also critiqued the moral character of those who sought political power, arguing that their motivations were often rooted in ambition, greed, or a desire for fame rather than a genuine concern for justice. In *The Republic*, he contrasts the philosopher-king, who rules with wisdom and selflessness, with the typical politician, who is driven by personal interests. This critique extended to the idea that political success in Athens was often achieved through flattery, bribery, or demagoguery, practices Socrates deemed incompatible with moral integrity. By refusing to engage in such tactics, he effectively distanced himself from a political arena he saw as irredeemably corrupt.

Furthermore, Socrates' focus on self-examination and the pursuit of wisdom led him to prioritize philosophical inquiry over political action. He believed that the greatest service one could render to society was to encourage individuals to question their assumptions and seek virtue, rather than to participate in a flawed political system. In *The Apology*, he describes his role as a "gadfly" to the Athenian state, provoking citizens to think critically rather than blindly following political leaders. This stance reflects his conviction that the corruption of politics could only be addressed through individual moral transformation, not through direct political involvement.

Lastly, Socrates' trial and execution underscore his refusal to compromise his principles for political expediency. When given the opportunity to propose a counter-penalty to his sentence, he declined to suggest exile or a fine, instead insisting on the truth of his philosophical mission. This act of defiance highlights his belief that the political system was not only corrupt but also incapable of recognizing or valuing genuine virtue. For Socrates, remaining politically inactive was not a sign of apathy but a deliberate choice to uphold his commitment to truth and justice in the face of a system he deemed unworthy.

Can Political Parties Legally Block Independent Candidates from Running?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Socrates avoids direct political involvement because he believes true change comes from improving individual souls through questioning and dialogue, not through holding office or engaging in partisan politics.

Socrates deeply cared about justice and the moral health of Athens, but he focused on examining the beliefs and values of individuals rather than participating in political institutions, which he saw as often corrupt or misguided.

Socrates criticized politicians to expose their ignorance and hypocrisy, not to gain power. His goal was to encourage self-reflection and wisdom, which he believed were essential for a just society, even if he didn’t seek political office.