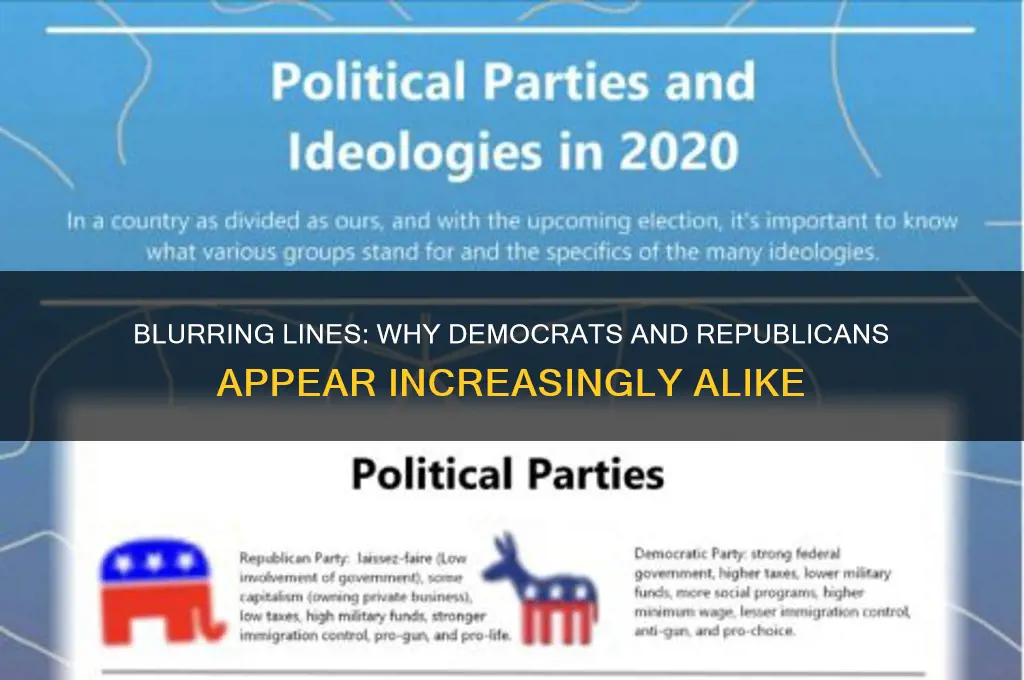

The perception that the two major political parties in many democratic systems, such as the Democratic and Republican parties in the United States, seem increasingly similar has sparked widespread debate and frustration among voters. While both parties claim distinct ideologies—traditionally, Democrats leaning toward progressive policies and Republicans toward conservative principles—critics argue that their stances on key issues like corporate influence, foreign policy, and fiscal management often overlap, creating a blurred line between them. This similarity is frequently attributed to factors like the influence of lobbyists, the need to appeal to a broad electorate, and the structural constraints of a two-party system, which incentivize moderation and compromise over ideological purity. As a result, many voters feel disenfranchised, believing their choices are limited to two sides of the same coin rather than genuine alternatives.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Centrist Convergence | Both parties often adopt centrist policies to appeal to a broader electorate. |

| Corporate Influence | Heavy reliance on corporate donations and lobbying, leading to similar policy stances. |

| Electoral Strategy | Focus on swing states and moderate voters, resulting in similar messaging. |

| Bipartisan Compromise | Frequent collaboration on key legislation to maintain political stability. |

| Elite Dominance | Both parties are dominated by political and economic elites with shared interests. |

| Media Framing | Mainstream media often narrows the political discourse to a centrist viewpoint. |

| Polarization Paradox | Despite public perception of polarization, both parties avoid extreme policies. |

| Global Economic Alignment | Shared support for global capitalism and free trade agreements. |

| Incrementalism | Preference for incremental changes over radical reforms to maintain status quo. |

| Voter Apathy | Low voter turnout and disillusionment reduce pressure for distinct policies. |

| Party Establishment Control | Party leadership often prioritizes maintaining power over ideological purity. |

| Cultural Similarities | Overlapping cultural values among party elites despite public disagreements. |

| Fear of Third Parties | Both parties work to marginalize third-party candidates to maintain dominance. |

| Data-Driven Campaigns | Use of similar data analytics and polling strategies to target voters. |

| Historical Precedent | Long-standing tradition of two-party dominance shaping political norms. |

Explore related products

$10.99 $19.99

$2.99 $17.99

What You'll Learn

- Shared Donor Influence: Both parties rely on similar corporate and wealthy donors, shaping their policies

- Centrist Strategy: Appeals to moderate voters often lead to overlapping, middle-ground positions

- Institutional Constraints: The two-party system limits radical ideas, encouraging conformity

- Media Framing: News outlets often highlight similarities, downplaying differences for simplicity

- Pragmatic Governance: Real-world compromises force both parties to adopt similar practical solutions

Shared Donor Influence: Both parties rely on similar corporate and wealthy donors, shaping their policies

Money talks, and in American politics, it often dictates the conversation. Both major parties, despite their ideological posturing, find themselves beholden to a shared pool of wealthy donors and corporate interests. This financial dependency creates a gravitational pull towards policies that favor the economic elite, regardless of party affiliation.

Consider the pharmaceutical industry. Both Democrats and Republicans receive substantial campaign contributions from drug companies. As a result, meaningful reforms to lower drug prices, such as allowing Medicare to negotiate directly with manufacturers, consistently face bipartisan resistance. The profit margins of these corporations become a higher priority than the financial burden on everyday Americans.

This dynamic isn't limited to healthcare. Wall Street firms, fossil fuel giants, and tech monopolies all have a seat at the table, funding campaigns and gaining access to policymakers. Their influence manifests in tax breaks, deregulation, and policies that prioritize corporate growth over addressing income inequality or environmental sustainability.

State Farm's Political Donations: Which Party Received Their Support?

You may want to see also

Centrist Strategy: Appeals to moderate voters often lead to overlapping, middle-ground positions

In the pursuit of electoral victory, political parties often pivot toward the center, recognizing that moderate voters frequently hold the balance of power. This strategic shift is not merely a tactical maneuver but a calculated response to the demographic and ideological makeup of the electorate. Moderates, who often prioritize pragmatism over ideological purity, constitute a significant portion of the voting population. By tailoring their platforms to appeal to this group, parties inevitably converge on middle-ground positions, blurring the distinctions between them. For instance, both major parties in the U.S. often emphasize bipartisanship and compromise, even if their bases demand more extreme stances. This convergence is not a sign of weakness but a reflection of the electoral math: winning the center is often the surest path to victory.

Consider the policy arena, where centrist strategies manifest in tangible ways. On issues like healthcare, taxation, and climate change, both parties often propose solutions that blend elements of their traditional ideologies. For example, while one party might advocate for a public option in healthcare, the other might support subsidies for private insurance—both positions aimed at appealing to moderates who value affordability and choice. This overlap is not accidental but a direct result of polling data and focus groups that reveal moderate voters’ preferences. Parties that ignore these preferences risk alienating a critical bloc, making centrist appeals a necessity rather than a choice.

However, this strategy is not without risks. By focusing on moderate voters, parties may dilute their core messages, alienating their bases. Activists and ideologically committed voters often view centrist positions as watered-down compromises that fail to address systemic issues. This tension can lead to internal party conflicts, as seen in recent years with progressive and conservative wings pushing back against their respective party leaderships. Yet, the allure of the center remains strong, as it offers a broader coalition-building opportunity that can offset losses from disillusioned base voters.

Practical implementation of centrist strategies requires finesse. Parties must strike a balance between adopting moderate positions and maintaining credibility with their core supporters. One effective approach is to frame centrist policies as pragmatic solutions rather than ideological concessions. For example, a party might highlight how a middle-ground approach to immigration reform—combining border security with pathways to citizenship—addresses both humanitarian concerns and national security interests. Such messaging resonates with moderates while minimizing backlash from the base.

In conclusion, the centrist strategy is a double-edged sword. While it fosters overlapping, middle-ground positions that make the two major parties appear similar, it also reflects a pragmatic response to the electoral landscape. Parties that master this approach can dominate the political center, but they must navigate the inherent risks of alienating their bases. For voters, understanding this dynamic provides insight into why political differences often seem muted, even as ideological polarization intensifies. The center, it appears, is not just a position—it’s a battlefield.

Understanding Political Parties: Key Functions Explained for Class 10 Students

You may want to see also

Institutional Constraints: The two-party system limits radical ideas, encouraging conformity

The two-party system in the United States, dominated by Democrats and Republicans, operates within a framework that inherently discourages radical ideas. This isn't a bug; it's a feature. The system is designed to prioritize stability over innovation, incremental change over revolutionary upheaval.

Think of it like a heavily trafficked highway. While it efficiently moves large numbers of people, it's not built for experimental vehicles or sudden U-turns. The two-party system, with its winner-takes-all electoral college and first-past-the-post voting, functions similarly, funneling political energy into two broad lanes, leaving little room for alternatives.

This structural constraint manifests in several ways. Firstly, the need to appeal to a broad electorate pushes both parties towards the center. Candidates who espouse extreme positions risk alienating moderate voters, crucial for winning elections. This "median voter theorem" effectively acts as a gravitational force pulling both parties towards the political center, blurring ideological distinctions.

Secondly, the power of incumbency and established party machinery creates a formidable barrier to entry for third parties. Access to funding, media coverage, and ballot access are heavily tilted in favor of the established parties, making it incredibly difficult for new voices to gain traction. This effectively stifles the emergence of parties advocating for radical change, further entrenching the status quo.

The consequences of this system are profound. It limits the range of policy options available to voters, often reducing complex issues to binary choices. This can lead to a sense of disillusionment and political apathy, as voters feel their voices are not truly represented. Furthermore, the suppression of radical ideas can hinder necessary societal progress. Historically, movements for civil rights, women's suffrage, and environmental protection often originated from outside the mainstream political sphere, highlighting the importance of allowing space for dissenting voices.

While the two-party system provides stability and a degree of predictability, it comes at the cost of ideological diversity and the potential for transformative change. Recognizing these institutional constraints is crucial for understanding why the two major parties often appear more similar than different, and for exploring potential reforms that could foster a more inclusive and dynamic political landscape.

Are Political Parties Modern Coalitions? Exploring Unity and Division in Politics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Media Framing: News outlets often highlight similarities, downplaying differences for simplicity

News outlets thrive on simplicity. Complex political landscapes don’t sell headlines. To capture attention, journalists often frame stories by amplifying similarities between the two major parties, reducing nuanced debates to digestible soundbites. For instance, a news segment might juxtapose a Democrat and a Republican both supporting infrastructure spending, ignoring the stark differences in their funding priorities or ideological underpinnings. This framing isn’t malicious—it’s practical. Audiences retain simple narratives better than intricate policy distinctions. However, this approach inadvertently reinforces the perception that the parties are indistinguishable, even when their platforms diverge significantly.

Consider the 2020 election coverage. Many outlets focused on both candidates’ appeals to “working-class voters,” creating a false equivalence between their economic policies. While both parties addressed job creation, their methods—tax cuts versus government spending—were fundamentally opposed. By highlighting the shared theme of economic concern, media simplified the narrative, leaving viewers with the impression that the parties were more alike than different. This isn’t just about laziness; it’s about catering to audience preferences for clarity over complexity.

To counteract this, consumers must actively seek out comparative analyses rather than relying on surface-level reporting. Start by identifying key policy areas—healthcare, climate, taxation—and cross-reference party platforms directly. Tools like Ballotpedia or OnTheIssues provide non-partisan breakdowns of candidate stances. When engaging with news, ask: *What’s being omitted?* If a story emphasizes similarities, dig deeper into the “how” and “why” behind those policies. For example, both parties might support education reform, but one may prioritize charter schools while the other focuses on public school funding.

A cautionary note: Even fact-checking sites can fall into this trap by focusing on truthfulness rather than ideological depth. A statement can be factually accurate yet fail to capture the full spectrum of a party’s agenda. To avoid this, diversify your sources. Include think tanks, academic journals, and international media, which often provide broader context. For instance, BBC or Al Jazeera might frame U.S. politics in ways that domestic outlets overlook, offering a fresh perspective on party distinctions.

Ultimately, media framing isn’t a conspiracy—it’s a byproduct of the industry’s demand for brevity and engagement. By understanding this mechanism, readers can become more discerning. Treat news as a starting point, not the final word. Engage critically, seek depth, and remember: simplicity in reporting doesn’t equate to simplicity in reality. The parties may share surface-level similarities, but their differences are where the stakes truly lie.

Understanding the Timing of Political Polls: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Pragmatic Governance: Real-world compromises force both parties to adopt similar practical solutions

In the realm of governance, the adage "politics is the art of the possible" rings particularly true. Pragmatic governance demands that leaders navigate complex realities, often forcing both major political parties to converge on similar solutions. Consider infrastructure spending: regardless of party affiliation, governments must maintain roads, bridges, and public transit to ensure economic stability. Democrats and Republicans may debate funding sources—tax increases versus budget reallocations—but the end goal of functional infrastructure remains unchanged. This convergence isn’t ideological surrender; it’s a practical acknowledgment that certain problems require immediate, tangible action.

To illustrate, examine the bipartisan support for disaster relief funding. When hurricanes devastate coastal states or wildfires ravage the West, partisan bickering takes a backseat to emergency response. Both parties recognize the urgency of allocating resources swiftly, even if they differ on long-term climate policies. This pattern repeats in healthcare: while Democrats push for expanded coverage and Republicans advocate for market-based solutions, both parties have historically supported incremental fixes like the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which bridges ideological gaps with practical compromises.

However, pragmatic governance isn’t without pitfalls. Critics argue that this approach can lead to watered-down policies that fail to address root causes. For instance, bipartisan criminal justice reforms often focus on reducing prison populations through sentencing adjustments, but they rarely tackle systemic issues like racial bias or police accountability. To avoid such shortcomings, policymakers must pair pragmatism with long-term vision. A useful framework is the "80/20 rule": focus 80% of efforts on achievable, bipartisan solutions while reserving 20% for bold, transformative ideas that challenge the status quo.

For citizens, understanding pragmatic governance offers a lens to evaluate political actions. When a policy seems suspiciously similar across party lines, ask: Is this a genuine compromise, or a superficial agreement that avoids hard choices? For example, both parties often tout job creation, but their methods—tax cuts versus public investment—differ significantly. By scrutinizing these nuances, voters can distinguish between pragmatic problem-solving and political theater. Ultimately, pragmatic governance isn’t about erasing differences; it’s about finding common ground where action is non-negotiable.

Los Angeles' Political Landscape: Understanding the City's Dominant Party

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The two major parties, Democrats and Republicans, often appear similar because they both operate within a two-party system that incentivizes appealing to a broad, centrist electorate to win elections. This leads to overlapping positions on many issues to attract moderate voters.

While the parties have distinct ideological bases (e.g., Democrats lean progressive and Republicans lean conservative), they often moderate their stances to appeal to swing voters and avoid alienating independents, making their policies seem more alike in practice.

Third parties face significant structural barriers, such as winner-take-all electoral systems and limited funding or media coverage, which make it difficult for them to gain traction and present a viable alternative to the major parties.

Both parties rely on large donors and lobbying groups for funding and support, which can lead to similar policy outcomes, especially on issues like corporate tax breaks or trade agreements, further blurring their differences.