Political parties are often viewed as unified entities with shared ideologies and goals, but a closer examination reveals that they frequently function more like coalitions, comprising diverse factions with varying interests and priorities. Within a single party, members may hold differing views on key issues, from economic policies to social values, creating internal dynamics that resemble those of broader alliances. This coalition-like structure is evident in the compromises parties make to maintain unity, the strategic alliances formed between factions, and the balancing acts leaders perform to appease different groups. Understanding parties as coalitions sheds light on their internal complexities and explains why they sometimes struggle to present a cohesive front, particularly in polarized political landscapes.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Political parties are not inherently coalitions, but they can form coalitions with other parties for strategic purposes, such as gaining majority power or achieving specific policy goals. |

| Structure | Political parties are typically organized around a shared ideology, platform, or leader, whereas coalitions are temporary alliances between distinct parties with differing ideologies. |

| Membership | Parties have a defined membership base that aligns with their core principles, while coalitions consist of members from multiple parties who may not share the same core beliefs. |

| Decision-Making | Parties make decisions internally through established hierarchies, whereas coalitions require negotiation and consensus-building among participating parties. |

| Duration | Parties are long-term organizations, while coalitions are often formed for specific elections, legislative periods, or policy objectives. |

| Ideological Cohesion | Parties aim for ideological cohesion among members, whereas coalitions inherently involve ideological diversity. |

| Examples | In countries like Germany and India, coalitions are common for forming governments. In contrast, parties like the U.S. Democratic or Republican parties operate independently but may form informal alliances on specific issues. |

| Flexibility | Coalitions offer flexibility in adapting to political landscapes, while parties maintain a more rigid ideological stance. |

| Voter Perception | Voters typically identify with a party based on its consistent ideology, whereas coalitions may be seen as pragmatic but less ideologically pure. |

| Policy Implementation | Parties aim to implement their full agenda, while coalitions often compromise on policies to satisfy all participating parties. |

Explore related products

$9.99

$192 $72.99

What You'll Learn

- Formation of Coalitions: How parties form alliances based on shared goals or electoral strategies

- Ideological Compromises: Balancing diverse ideologies within coalitions to maintain unity and appeal

- Power Distribution: Negotiating leadership roles and policy influence among coalition partners

- Electoral Incentives: How coalition-building impacts voter perception and election outcomes

- Stability Challenges: Managing internal conflicts and external pressures in coalition governments

Formation of Coalitions: How parties form alliances based on shared goals or electoral strategies

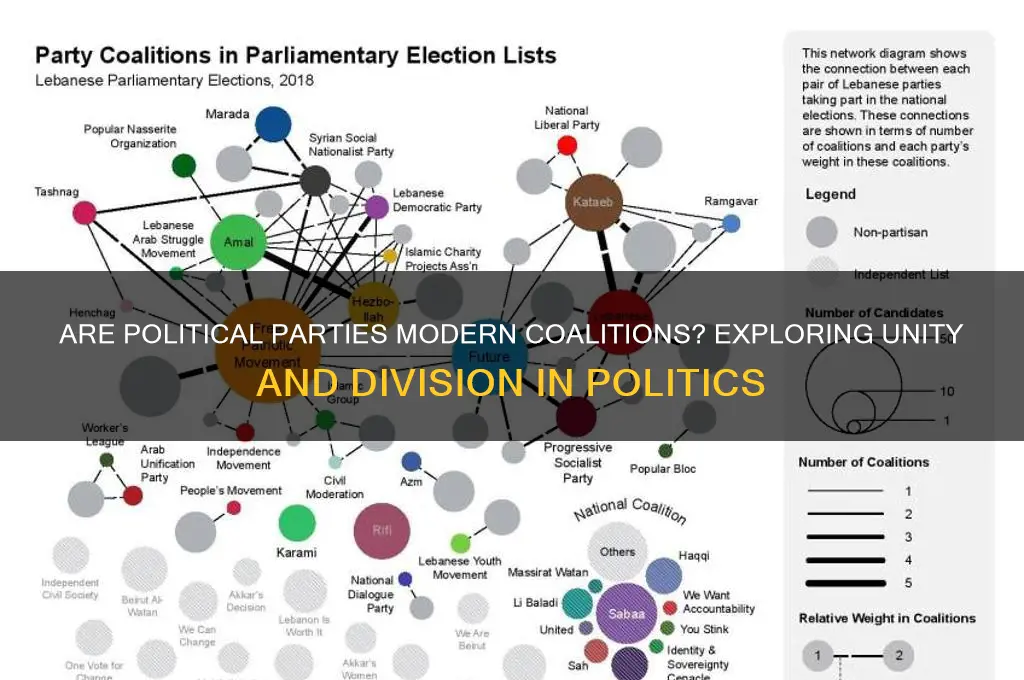

The formation of coalitions among political parties is a strategic process driven by shared goals, electoral advantages, and the need to secure political power. Coalitions are not inherently the same as political parties, but parties often form alliances to achieve common objectives, particularly in systems where no single party can secure a majority. These alliances are typically forged based on ideological alignment, policy convergence, or pragmatic electoral strategies. For instance, parties with similar policy platforms may unite to amplify their influence and implement shared agendas. This is evident in countries like Germany, where the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Christian Social Union (CSU) maintain a longstanding coalition despite being separate entities.

Shared goals play a pivotal role in coalition formation. Parties with overlapping ideologies or policy priorities are more likely to collaborate. For example, left-leaning parties may ally to promote social welfare programs, while right-leaning parties might unite around fiscal conservatism. In India, the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) and National Democratic Alliance (NDA) are coalitions of multiple parties with shared visions for governance. Such alliances allow smaller parties to contribute to policy-making while providing larger parties with the numbers needed to form a government. This alignment of goals ensures that coalition partners can work cohesively despite their individual differences.

Electoral strategies also drive coalition formation, particularly in proportional representation systems where no single party dominates. Parties may form pre-election alliances to pool resources, expand their voter base, and increase their chances of winning a majority. Post-election coalitions, on the other hand, are often formed when no party secures a clear mandate. In such cases, parties negotiate based on seat distribution, ministerial positions, and policy concessions. For instance, in Israel, coalitions are essential due to the fragmented party system, with parties forming alliances to meet the Knesset’s governing threshold.

The process of coalition formation involves negotiation and compromise. Parties must balance their core principles with the need for consensus. This often requires sacrificing certain policy demands or agreeing to power-sharing arrangements. For example, in Belgium, coalitions between Flemish and Walloon parties are necessary for governance, despite linguistic and cultural divides. Successful coalitions depend on clear agreements, trust, and a commitment to shared objectives. However, internal conflicts and differing priorities can lead to instability, as seen in Italy’s frequent coalition governments.

Ultimately, while political parties are not inherently coalitions, the formation of alliances based on shared goals or electoral strategies is a common feature of modern politics. These coalitions serve as mechanisms for parties to enhance their influence, achieve policy objectives, and secure political power. Whether driven by ideology or pragmatism, coalition-building requires careful negotiation and a willingness to collaborate. Understanding this dynamic is essential to grasping how political parties operate within complex electoral landscapes.

Can Political Parties Text You? Understanding Campaign Communication Laws

You may want to see also

Ideological Compromises: Balancing diverse ideologies within coalitions to maintain unity and appeal

Political parties often function as coalitions, bringing together individuals and groups with diverse ideologies, interests, and priorities under a common banner. This inherent diversity is both a strength and a challenge, as it allows parties to appeal to a broader electorate but also requires careful management of ideological differences. Ideological compromises are essential for maintaining unity and ensuring the coalition remains functional and appealing to voters. These compromises involve finding common ground, prioritizing shared goals, and sometimes setting aside extreme positions to foster cohesion. Without such compromises, internal conflicts can erode party unity, weaken public appeal, and ultimately undermine electoral success.

Balancing diverse ideologies within a coalition demands strategic leadership that can navigate competing interests while preserving the party’s core identity. Leaders must act as mediators, identifying areas where compromise is feasible without alienating key factions. For instance, a party might adopt a platform that includes progressive social policies alongside moderate economic measures, appealing to both left-leaning and centrist voters. This approach requires a delicate touch, as over-compromising can dilute the party’s message, while under-compromising risks fracturing the coalition. Effective leaders also communicate the rationale behind compromises, ensuring members understand the trade-offs and remain committed to the party’s broader objectives.

One practical strategy for managing ideological diversity is the use of policy bundling, where disparate factions agree to support a mix of policies that reflect their respective priorities. For example, a coalition might pair environmental regulations favored by progressives with tax cuts supported by conservatives, creating a balanced agenda that satisfies multiple constituencies. This approach not only fosters internal unity but also enhances external appeal by presenting the party as pragmatic and inclusive. However, policy bundling requires transparency and fairness to avoid perceptions of favoritism or marginalization, which can breed resentment and dissent.

Another critical aspect of ideological compromise is the management of public messaging. Coalitions must project a unified front to voters, even when internal disagreements persist. This involves crafting narratives that highlight shared values and goals while downplaying differences. For instance, a party might emphasize themes like economic opportunity or social justice, which resonate across ideological lines, rather than focusing on divisive issues. Effective messaging also involves acknowledging diversity as a strength, positioning the party as a broad tent capable of representing varied perspectives. This approach builds trust with voters and reinforces the coalition’s credibility as a governing entity.

Finally, sustaining ideological compromises requires institutional mechanisms that formalize the process of negotiation and decision-making. Internal committees, caucuses, or forums can provide platforms for factions to voice their concerns and negotiate outcomes. Rules for consensus-building, such as supermajority requirements or proportional representation in leadership positions, can also ensure that no single group dominates the coalition. These mechanisms not only facilitate compromise but also signal to members that their voices are valued, fostering a sense of fairness and mutual respect. By embedding compromise into the party’s structure, coalitions can navigate ideological diversity more effectively and maintain their appeal over time.

In conclusion, ideological compromises are vital for balancing diverse ideologies within political coalitions, ensuring unity and broad appeal. Through strategic leadership, policy bundling, unified messaging, and institutional mechanisms, parties can manage internal differences while presenting a cohesive vision to the public. While compromise is not without challenges, it remains a cornerstone of successful coalition-building, enabling parties to harness their diversity as a source of strength rather than division.

Federalists vs. Anti-Federalists: Were They America's First Political Parties?

You may want to see also

Power Distribution: Negotiating leadership roles and policy influence among coalition partners

In the context of political parties functioning as coalitions, power distribution becomes a critical aspect of their internal dynamics. When multiple factions or interest groups come together under a single party umbrella, negotiating leadership roles and policy influence is essential to maintain cohesion and achieve collective goals. This negotiation often involves a delicate balance between recognizing the strengths and contributions of each partner while ensuring that no single group dominates the decision-making process. Leadership roles, such as party chairmanship, parliamentary leadership, or cabinet positions, are typically allocated based on the relative strength, electoral support, or expertise of each coalition partner. For instance, a faction with strong grassroots support might be given a prominent organizational role, while another with policy expertise could lead key committees or ministries.

Policy influence is another critical dimension of power distribution within political party coalitions. Each partner brings its own ideological priorities, policy agendas, and constituent demands to the table. Negotiating policy influence requires creating mechanisms that allow all partners to have a say in shaping the party's platform and legislative priorities. This can be achieved through formal structures like policy councils or steering committees, where representatives from each faction debate and negotiate compromises. For example, a coalition partner advocating for environmental policies might secure commitments for green initiatives in exchange for supporting another partner's economic agenda. Such trade-offs are common and reflect the pragmatic nature of coalition politics.

The process of negotiating power distribution is often formalized through coalition agreements, which outline the terms of cooperation, including leadership roles, policy commitments, and dispute resolution mechanisms. These agreements serve as binding contracts that provide clarity and stability to the coalition. However, they also require flexibility, as political landscapes can shift, necessitating renegotiation or adjustments. Effective coalition management involves regular communication, trust-building, and a shared commitment to the coalition's overarching goals, even when individual partners must compromise on specific issues.

One challenge in power distribution is managing the tension between equality and proportionality. Smaller coalition partners may demand equal representation to safeguard their interests, while larger partners argue for influence proportional to their size or electoral contributions. Striking a balance often involves creative solutions, such as rotating leadership positions, granting veto powers on specific issues, or establishing weighted voting systems within decision-making bodies. Additionally, external factors like electoral performance, public opinion, and the broader political environment can influence power dynamics, requiring coalition partners to adapt their strategies accordingly.

Ultimately, successful power distribution in political party coalitions hinges on mutual respect, strategic foresight, and a willingness to prioritize collective success over individual gains. Leaders must act as mediators, fostering an environment where all partners feel valued and their contributions are recognized. By effectively negotiating leadership roles and policy influence, coalitions can harness their diversity as a strength, enabling them to address complex challenges and maintain broad-based support. This collaborative approach not only enhances the party's internal stability but also strengthens its ability to govern effectively and respond to the needs of its constituents.

Can Nonprofits Legally Donate to Political Parties? Key Rules Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$23.99 $36.95

$182.59 $56.99

Electoral Incentives: How coalition-building impacts voter perception and election outcomes

Coalition-building among political parties significantly shapes electoral incentives by influencing voter perception and election outcomes. When parties form coalitions, they often aim to broaden their appeal by combining diverse policy platforms and voter bases. This strategy can attract a wider electorate, particularly in systems where no single party achieves a majority. However, it also introduces complexity, as voters must assess not only individual parties but also the dynamics and compromises within the coalition. For instance, a coalition between a center-left and a green party might appeal to progressive voters but could alienate those who prioritize economic stability over environmental policies. Thus, coalition-building creates a delicate balance between expanding electoral reach and risking voter disillusionment due to perceived ideological inconsistencies.

Voter perception of coalitions is heavily influenced by the clarity and credibility of the alliance. When coalitions present a unified vision and communicate shared goals effectively, they can enhance voter confidence. For example, a coalition that clearly outlines its joint agenda on healthcare reform may attract voters who value collaborative problem-solving. Conversely, coalitions perceived as opportunistic or unstable can deter voters who prioritize consistency and trustworthiness. Electoral incentives thus push parties to invest in transparent communication and cohesive messaging to mitigate skepticism. This dynamic underscores the importance of strategic coalition management in shaping public trust and electoral viability.

The impact of coalition-building on election outcomes is also evident in vote distribution and strategic voting behavior. In proportional representation systems, smaller parties may benefit from coalitions by surpassing electoral thresholds or pooling votes to secure more seats. However, this can lead to strategic voting, where voters support a coalition partner they perceive as more viable, even if it is not their first choice. For instance, a voter might support a larger party in a coalition to prevent the success of an opposing bloc. This behavior highlights how coalitions alter electoral calculations, incentivizing parties to prioritize alliance-building over individual party branding.

Moreover, coalition-building affects voter turnout and engagement. Coalitions can mobilize voters by offering a broader platform that addresses multiple concerns, thereby increasing turnout among diverse demographics. For example, a coalition focusing on both economic and social issues might energize both working-class and socially progressive voters. Conversely, overly complex or contentious coalitions may discourage participation, particularly among undecided or disillusioned voters. Thus, parties must carefully navigate coalition dynamics to maximize turnout and engagement, aligning their strategies with the preferences of their target electorate.

Finally, the long-term electoral incentives of coalition-building depend on post-election performance and stability. Successful coalitions that deliver on their promises can solidify voter loyalty and establish a strong electoral base for future elections. However, coalitions that fail to govern effectively or collapse prematurely risk damaging the reputations of all involved parties. This creates a strong incentive for parties to prioritize governance over short-term political gains, ensuring that coalitions are not just electoral tools but also vehicles for sustainable policy implementation. In essence, coalition-building is a high-stakes strategy that reshapes electoral landscapes by redefining voter perceptions, influencing outcomes, and determining the long-term viability of political parties.

Political Parties and Interest Groups: Strengthening or Undermining American Democracy?

You may want to see also

Stability Challenges: Managing internal conflicts and external pressures in coalition governments

Coalition governments, by their very nature, are formed when multiple political parties come together to share power, often due to no single party securing a majority. While this arrangement can foster inclusivity and diverse representation, it inherently introduces stability challenges stemming from both internal conflicts and external pressures. Internally, coalition partners often have differing ideologies, policy priorities, and power dynamics, which can lead to friction. For instance, parties may disagree on key legislative agendas, budget allocations, or ministerial appointments, creating a constant need for negotiation and compromise. Managing these differences requires strong leadership and clear communication channels to prevent gridlock or, worse, the collapse of the government. Effective coalition management often involves drafting detailed coalition agreements that outline shared goals and dispute resolution mechanisms, but even these documents cannot eliminate the potential for conflict.

One of the most significant internal challenges is the distribution of power and resources among coalition partners. Smaller parties may feel marginalized if larger parties dominate decision-making, leading to resentment and instability. Additionally, individual leaders within the coalition may pursue personal or party interests over collective goals, further exacerbating tensions. For example, a party leader might threaten to withdraw from the coalition to gain leverage on a specific issue, risking the government’s survival. Such dynamics highlight the delicate balance coalition leaders must maintain to ensure stability while addressing the legitimate concerns of all partners.

Externally, coalition governments face pressures from opposition parties, the media, and the public, all of whom scrutinize their every move. Opposition parties often exploit internal divisions to undermine the government’s credibility, while media coverage can amplify conflicts, creating a perception of instability even when issues are minor. Public opinion is equally critical, as citizens may grow disillusioned with a government that appears indecisive or dysfunctional. External shocks, such as economic crises or international conflicts, further test coalition cohesion, as partners may disagree on how to respond, leaving the government vulnerable to criticism and potential collapse.

Another external challenge arises from the need to maintain credibility with voters and stakeholders. Coalition governments must deliver on their promises despite internal disagreements, which can be difficult when compromises dilute policy effectiveness. For instance, a coalition might water down a controversial reform to satisfy all partners, only to face backlash from voters who perceive the government as weak or unfocused. This dynamic underscores the importance of strategic communication and transparency in managing public expectations and maintaining trust.

Ultimately, managing stability in coalition governments requires a combination of proactive leadership, institutional mechanisms, and a shared commitment to governance. Leaders must foster a culture of collaboration, prioritize collective goals over partisan interests, and be willing to make tough decisions to preserve unity. Institutional tools, such as formal coalition agreements and regular consultative processes, can help mitigate conflicts before they escalate. However, the success of a coalition government often hinges on the ability of its members to navigate internal and external pressures with resilience and adaptability, ensuring that the government remains functional and effective in serving the public interest.

Interest Groups vs. Political Parties: Which Holds More Power in Politics?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, political parties are not always coalitions. While some parties form coalitions with other parties or groups to achieve common goals, many operate independently with their own distinct ideologies and platforms.

A political party is a single organization with a unified platform and membership, whereas a coalition is an alliance of multiple parties or groups that come together temporarily to achieve specific objectives, often during elections or governance.

No, political parties may form coalitions during elections to pool resources and increase their chances of winning, but they can also form coalitions during governance to secure a majority or implement policies that require broader support.

Yes, a political party can be part of multiple coalitions, depending on the context and goals. For example, a party might join one coalition at the national level and another at the regional or local level.

No, coalitions are typically temporary arrangements formed for specific purposes, such as elections or policy implementation. Once the goals are achieved or circumstances change, coalitions may dissolve, and parties may return to independent operations.