Political polls often differ due to variations in methodology, sample size, timing, and question wording, which can significantly influence results. Methodologies such as online surveys, phone interviews, or in-person polling yield distinct outcomes based on the demographics and accessibility of respondents. Sample size plays a critical role, as smaller samples may produce less reliable data compared to larger, more representative groups. Timing is another factor, as public opinion can shift rapidly in response to events, making polls conducted even days apart appear contradictory. Additionally, the phrasing of questions can subtly sway responses, leading to discrepancies between polls. These differences highlight the complexity of measuring public sentiment and underscore the importance of critically evaluating polling data.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Sampling Method | Probability vs. non-probability sampling; online, phone, or in-person methods. |

| Sample Size | Larger samples reduce margin of error; smaller samples increase variability. |

| Population Representation | Differences in demographic weighting (e.g., age, race, education, geographic location). |

| Question Wording | Variations in phrasing can influence responses (e.g., leading questions). |

| Timing of Poll | Conducted during different periods (e.g., before/after debates, scandals, or events). |

| Response Rate | Higher response rates generally improve accuracy; low response rates may skew results. |

| Likely Voter Models | Different assumptions about voter turnout can lead to varying results. |

| Margin of Error | Varies based on sample size and methodology; wider margins increase uncertainty. |

| Pollster House Effects | Consistent biases or tendencies of specific polling organizations. |

| Undecided or Refusal Rates | Handling of undecided voters or refusals to answer can differ across polls. |

| Mode Effects | Differences in response patterns based on survey mode (e.g., phone vs. online). |

| Weighting Adjustments | Adjustments for under- or over-represented groups in the sample. |

| Contextual Factors | External events (e.g., economic shifts, scandals) influencing public opinion at the time. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Methodology Variations: Different sampling, weighting, and question phrasing affect results significantly across polls

- Timing Differences: Polls conducted at varying times capture shifting public opinions and events

- Population Sampling: Variances in demographics, geography, and voter likelihood skew outcomes

- Response Bias: Non-response, social desirability, and partisan reluctance distort poll accuracy

- Pollster House Effects: Consistent methodological choices by pollsters lead to systematic result differences

Methodology Variations: Different sampling, weighting, and question phrasing affect results significantly across polls

Political polls often yield differing results, and one of the primary reasons for these discrepancies lies in methodology variations. The way polls are conducted—from sampling techniques to weighting methods and question phrasing—can significantly influence outcomes. Each of these elements introduces variability, making it crucial to understand their impact on poll results.

Sampling is the foundation of any poll, yet it is a common source of variation. Pollsters use different sampling methods, such as random sampling, stratified sampling, or convenience sampling, each with its own strengths and limitations. For instance, a poll relying on landline phones may underrepresent younger voters who primarily use mobile phones, skewing results. Similarly, online polls often attract self-selected participants, which can lead to biased samples. The size of the sample also matters; smaller samples tend to have larger margins of error, making results less reliable. These differences in sampling approach can lead to divergent poll outcomes, even when measuring the same population.

Weighting is another critical factor that introduces variation. Pollsters adjust, or "weight," their raw data to ensure the sample reflects the demographic makeup of the target population. However, there is no universal standard for weighting, and pollsters may prioritize different demographics, such as age, race, education, or party affiliation. For example, one poll might heavily weight for education levels, while another focuses on geographic distribution. These decisions can amplify or diminish certain groups' influence on the results, leading to discrepancies across polls. The lack of a standardized weighting approach means that even polls with similar samples can produce different findings.

Question phrasing plays a surprisingly large role in shaping poll results. The way a question is worded can influence respondents' answers, a phenomenon known as "framing." For instance, asking, "Do you support increased government spending on healthcare?" may yield different responses than, "Do you think the government should allocate more funds to healthcare despite potential tax increases?" Leading or loaded questions can sway opinions, while ambiguous phrasing can confuse respondents. Additionally, the order of questions can affect answers, as earlier questions may prime respondents to answer later ones in a certain way. These subtle differences in phrasing and structure can lead to significant variations in poll outcomes.

In summary, methodology variations in sampling, weighting, and question phrasing are key drivers of differences in political poll results. Each of these elements involves subjective decisions by pollsters, which can introduce biases and inconsistencies. Understanding these variations is essential for interpreting poll results accurately and recognizing why polls often diverge, even when measuring the same political landscape. By scrutinizing the methodologies behind polls, consumers of political data can better assess their reliability and draw more informed conclusions.

Four Iconic Political Leaders Who Shaped Modern History

You may want to see also

Timing Differences: Polls conducted at varying times capture shifting public opinions and events

The timing of political polls plays a crucial role in the differences observed in their results. Public opinion is not static; it evolves in response to various factors such as political events, media coverage, and societal changes. Polls conducted at different times inherently capture these shifts, leading to variations in outcomes. For instance, a poll taken immediately after a significant political scandal will likely reflect heightened negative sentiment toward the involved party, whereas a poll conducted weeks later might show that the initial outrage has subsided. This temporal dynamic underscores why timing is a fundamental factor in poll discrepancies.

Another aspect of timing differences is the proximity to an election or key political event. Polls taken months before an election may reflect general attitudes or early preferences, but as the election nears, voters tend to become more informed and decisive. Late-stage polls often capture the impact of campaign strategies, debates, and last-minute developments, which can significantly alter public opinion. For example, a candidate who performs well in a debate might see a surge in support in polls conducted immediately afterward. Thus, the timing relative to critical events directly influences the results.

Moreover, seasonal or cyclical factors can also affect poll outcomes. Public opinion may fluctuate based on economic conditions, holiday periods, or even weather patterns. A poll conducted during an economic downturn might show increased dissatisfaction with the incumbent government, while one taken during a period of economic growth could yield more positive results. Similarly, polls taken during holidays or summer months, when political engagement is typically lower, may not accurately reflect the electorate's true sentiment compared to polls conducted during more politically active times.

Additionally, the speed at which news and information spread in today's digital age exacerbates timing differences. A viral news story or social media trend can rapidly shift public opinion within days or even hours. Polls conducted before such events will naturally differ from those taken afterward. This real-time influence of media and technology makes timing an even more critical variable in polling. Pollsters must account for these rapid shifts to ensure their results are relevant and accurate.

In conclusion, timing differences are a primary reason why political polls vary. Polls conducted at different times capture the dynamic nature of public opinion, influenced by events, proximity to elections, seasonal factors, and the rapid dissemination of information. Understanding this temporal dimension is essential for interpreting poll results and recognizing that no single poll can fully represent public sentiment at all times. Poll consumers must consider when a poll was conducted to contextualize its findings accurately.

Neil Gorsuch's Political Affiliation: Unraveling His Party Allegiance

You may want to see also

Population Sampling: Variances in demographics, geography, and voter likelihood skew outcomes

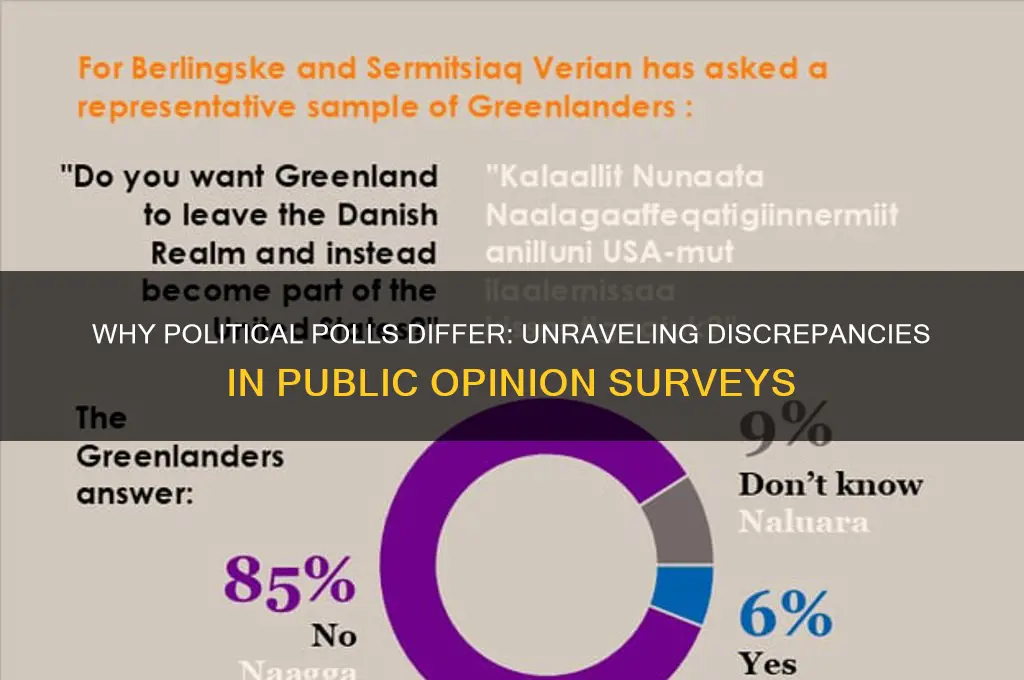

Political polls often differ due to variations in population sampling, a critical factor that hinges on how surveys capture the diversity of voters. One key aspect is demographic variance. Pollsters must ensure their samples reflect the population’s age, gender, race, education level, and income distribution. However, achieving this balance is challenging. For instance, younger voters may be underrepresented if pollsters rely heavily on landline phones, as younger demographics are more likely to use mobile phones exclusively. Similarly, minority groups may be overlooked if surveys are not conducted in multiple languages or in areas with diverse populations. These demographic gaps can skew results, as different groups often have distinct political preferences.

Geographic variance further complicates population sampling. Political opinions can vary drastically by region, state, or even neighborhood. A poll focusing on urban areas may overrepresent progressive views, while one centered on rural regions might tilt conservative. Additionally, some polls use state-level or national-level sampling, which can miss local nuances. For example, a national poll might not capture the unique political dynamics of a swing state, where small shifts in voter sentiment can have outsized impacts. Pollsters must carefully select geographic areas to ensure their samples are representative of the broader electorate, but this is often constrained by resources and time.

Voter likelihood is another critical factor that introduces variance. Not all registered voters turn out on Election Day, and pollsters use different methods to predict who is most likely to vote. Some polls screen for "likely voters" based on past voting behavior, interest in the election, or stated intent to vote. Others include all registered voters, regardless of their likelihood to participate. This distinction matters because likely voters often differ demographically and ideologically from the broader electorate. For instance, older voters are more likely to turn out, while younger voters, despite their numbers, often vote at lower rates. Polls that fail to account for voter likelihood may overestimate support for candidates who appeal to less reliable voter groups.

The interplay of these factors—demographics, geography, and voter likelihood—means that even small differences in sampling methodology can lead to significant variations in poll results. For example, a poll that oversamples urban, young voters might show stronger support for progressive policies, while another that focuses on rural, older voters could tilt conservative. Pollsters must make deliberate choices about how to weight and adjust their samples to reflect the true electorate, but these decisions are inherently subjective and can lead to diverging outcomes. As a result, understanding the sampling methodology behind a poll is essential for interpreting its results accurately.

In conclusion, population sampling is a cornerstone of polling accuracy, yet it is fraught with challenges. Variances in demographics, geography, and voter likelihood create inherent uncertainties that can skew outcomes. Pollsters strive to minimize these discrepancies through careful design and weighting, but no method is perfect. For consumers of political polls, recognizing these limitations is crucial for interpreting results critically and understanding why polls often differ. By acknowledging the complexities of population sampling, we can better appreciate the nuances of political polling and its role in shaping our understanding of public opinion.

Exploring France's Political Landscape: Do Parties Shape Its Democracy?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$19.91 $35

Response Bias: Non-response, social desirability, and partisan reluctance distort poll accuracy

Response Bias is a significant factor that contributes to the discrepancies observed in political polls, and it encompasses several key issues: non-response, social desirability bias, and partisan reluctance. Each of these elements can skew results, making it crucial for pollsters and analysts to understand and mitigate their effects.

Non-response bias occurs when certain groups of people are less likely to participate in polls, leading to an unrepresentative sample. For instance, individuals who are less politically engaged, younger voters, or those with lower socioeconomic status might be underrepresented in surveys. This bias can significantly distort poll results, as the opinions of more active or accessible groups may dominate, while the perspectives of less vocal or harder-to-reach populations are overlooked. Pollsters often attempt to correct for non-response by weighting their samples to match known demographic distributions, but this method is not foolproof and can still lead to inaccuracies.

Social desirability bias is another critical aspect of response bias. This phenomenon happens when respondents provide answers they believe are more socially acceptable rather than their true opinions. In political polling, this might manifest when individuals are hesitant to express support for controversial candidates or policies. For example, a person might claim to be undecided or support a more mainstream candidate when, in reality, they intend to vote for a more polarizing figure. This bias can lead to an overestimation of support for certain candidates or positions, particularly those considered more socially acceptable, while underestimating the backing for more divisive options.

Partisan reluctance further complicates poll accuracy. This bias occurs when supporters of a particular party or candidate are less willing to participate in polls, often due to distrust of the media or polling organizations. In recent years, this has been a notable issue, with some political groups expressing skepticism about the legitimacy of polls. As a result, polls may underrepresent the strength of certain political factions, leading to unexpected outcomes in elections. For instance, if supporters of a particular party are less likely to respond to polls, the polls may predict a closer race than what actually occurs on election day.

These forms of response bias collectively challenge the reliability of political polls. Non-response bias skews the sample, social desirability bias distorts individual responses, and partisan reluctance further imbalances the representation of different political groups. Pollsters employ various techniques to minimize these biases, such as adjusting samples to reflect demographic realities, using anonymous surveys to reduce social desirability bias, and conducting extensive outreach to engage reluctant participants. Despite these efforts, response bias remains a persistent issue, highlighting the complexity of accurately measuring public opinion in a politically diverse and often polarized society.

Understanding and addressing response bias is essential for improving the accuracy of political polls. By recognizing how non-response, social desirability, and partisan reluctance can distort results, pollsters and analysts can develop more robust methodologies. This includes not only refining sampling techniques but also enhancing the transparency and trustworthiness of polling processes to encourage broader and more honest participation. As political landscapes continue to evolve, so too must the approaches to measuring public sentiment, ensuring that polls remain a valuable tool for understanding democratic preferences.

Understanding the Roots of Organizational Politics in the Workplace

You may want to see also

Pollster House Effects: Consistent methodological choices by pollsters lead to systematic result differences

Pollster house effects refer to the systematic differences in polling results that arise from consistent methodological choices made by individual polling organizations. These choices, which are often rooted in a pollster’s proprietary techniques, can lead to predictable variations in outcomes across different polls, even when they are measuring the same population at the same time. House effects are not errors but rather the result of deliberate decisions about how to conduct surveys, from sampling methods to question wording and weighting adjustments. Understanding these effects is crucial for interpreting political polls accurately, as they highlight why polls from different sources may show divergent results.

One major source of house effects is the sampling methodology employed by pollsters. Different organizations use varying techniques to select their respondents, such as random digit dialing, voter registration lists, or online panels. For example, a pollster that relies heavily on landline phones may reach an older demographic, while another using mobile phones or online surveys might capture a younger, more tech-savvy audience. These sampling differences can skew results in favor of certain candidates or issues, depending on the demographic strengths of the candidates being polled. Over time, these consistent sampling choices create a "house effect" that distinguishes one pollster’s results from another’s.

Another significant factor contributing to house effects is the weighting process, where pollsters adjust their raw data to match the demographic profile of the population they are studying. Pollsters make decisions about which demographic variables to prioritize—such as age, race, gender, education, or party affiliation—and how heavily to weight each variable. For instance, one pollster might place greater emphasis on party affiliation, while another might focus more on education levels. These weighting decisions can systematically favor one candidate over another, depending on which demographic groups are over- or under-represented in the raw sample.

Question wording and order also play a role in house effects. Pollsters often phrase questions differently or ask them in a specific sequence, which can influence respondents’ answers. For example, a question about a candidate’s performance might be framed positively or negatively, or a series of questions might prime respondents to answer in a certain way. These subtle differences in survey design can lead to consistent variations in results across polls. Over time, such methodological choices become part of a pollster’s signature approach, contributing to their house effect.

Finally, the treatment of undecided or third-party voters can vary widely among pollsters and is another driver of house effects. Some pollsters may press undecided voters to choose between the major candidates, while others allow them to remain undecided or choose a third-party option. Similarly, the inclusion or exclusion of third-party candidates in the question can significantly alter the results. Pollsters with consistent policies on handling these groups will produce results that systematically differ from those of their peers, reinforcing their house effects.

In summary, pollster house effects arise from the consistent methodological choices that polling organizations make in sampling, weighting, question design, and data treatment. These choices are not random but are often deliberate and rooted in a pollster’s unique approach to survey research. While house effects can make it challenging to compare polls directly, they also provide valuable insights into the strengths and limitations of different polling methodologies. Recognizing and accounting for these effects is essential for anyone seeking to interpret political polls accurately and make informed judgments about public opinion.

Can Political Parties Legally Purchase Land? Exploring Ownership Rules

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political polls can differ due to variations in methodology, such as sampling techniques, question wording, and timing. Each organization may use different approaches to collect and analyze data, leading to discrepancies in results.

The timing of a poll can significantly impact results because public opinion can shift rapidly in response to events, debates, or news cycles. Polls conducted at different times may capture distinct snapshots of public sentiment.

Margins of error vary based on sample size and population diversity. Smaller sample sizes or more heterogeneous populations tend to produce larger margins of error, making the results less precise.

Yes, question wording can heavily influence responses. Leading questions, biased phrasing, or differences in how options are presented can skew results, leading to variations between polls.