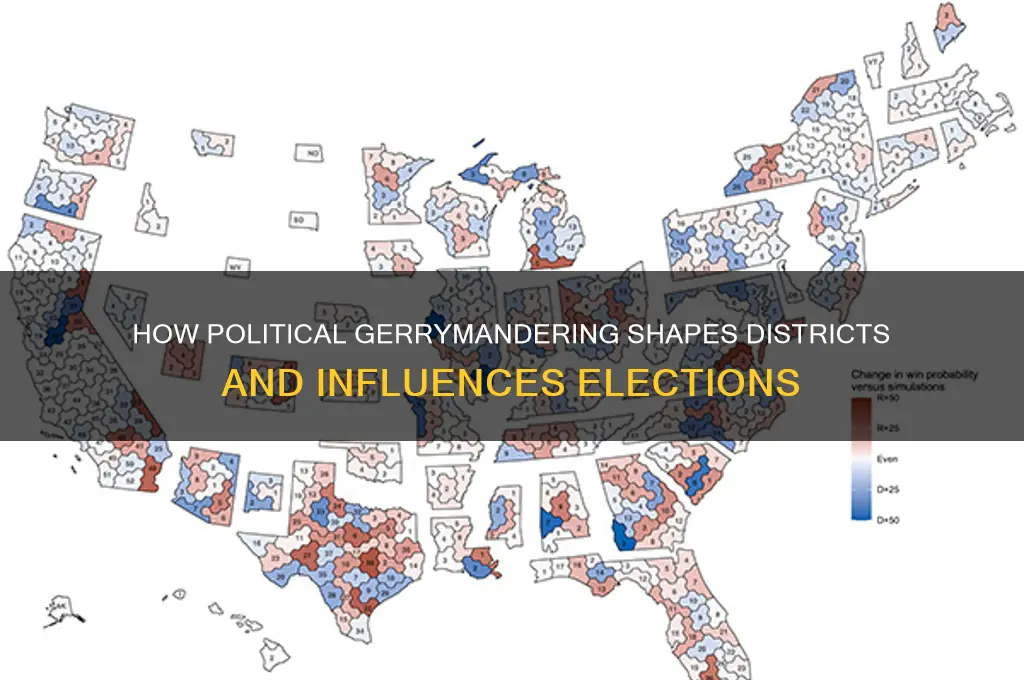

Political gerrymandering involves the manipulation of electoral district boundaries to favor one political party or group over another. This practice often results in oddly shaped districts that dilute the voting power of certain demographics, ensuring that the party in control can maintain or gain a legislative advantage. By strategically grouping or dispersing voters based on their political leanings, gerrymandering undermines fair representation and distorts the democratic process. Critics argue that it prioritizes partisan interests over the will of the electorate, while proponents sometimes defend it as a legitimate tool for political strategy. Understanding why and how gerrymandering occurs is crucial for addressing its impact on electoral integrity and democratic governance.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Concentrate Opposition Voters | Pack opposition voters into a small number of districts to reduce their influence in other areas. |

| Crack Opposition Strongholds | Split opposition strongholds across multiple districts to dilute their voting power. |

| Protect Incumbents | Draw district lines to ensure current officeholders face weaker opposition, increasing their chances of re-election. |

| Favor Specific Parties | Design districts to give one political party a disproportionate advantage in winning seats. |

| Minimize Competition | Create "safe" districts where one party dominates, reducing the need for competitive campaigns. |

| Reflect Demographic Changes | Manipulate boundaries to favor specific racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic groups aligned with a party’s interests. |

| Preserve Geographic Interests | Draw districts to favor rural or urban areas, depending on which aligns with the party’s base. |

| Exploit Voting Patterns | Use detailed voter data (e.g., past voting behavior) to strategically draw lines for partisan gain. |

| Reduce Accountability | Create districts where elected officials face little risk of losing their seats, reducing their accountability to voters. |

| Maintain Political Power | Ensure long-term control of legislative bodies by systematically favoring one party over others. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Maximizing Party Power: Strategically redrawing boundaries to consolidate voter bases and secure electoral advantages

- Diluting Opposition Votes: Spreading opposing voters thinly to minimize their impact on elections

- Protecting Incumbents: Crafting districts to ensure current officeholders face weaker challenges

- Racial or Group Targeting: Manipulating districts to favor or suppress specific demographic groups

- Securing Funding/Support: Designing districts to appeal to donors or key political allies

Maximizing Party Power: Strategically redrawing boundaries to consolidate voter bases and secure electoral advantages

Political gerrymandering is a strategic tool used by parties to maximize their power by redrawing district boundaries to consolidate voter bases and secure electoral advantages. This practice involves manipulating the geographic composition of districts to favor one party over another, often by packing opposition voters into a few districts or cracking them across multiple districts to dilute their influence. By carefully analyzing voter demographics, party strategists can design districts that ensure their candidates win by comfortable margins, thereby solidifying their control over legislative bodies. This methodical approach allows the dominant party to maintain or expand its political influence, even if its overall voter share remains relatively stable.

One key tactic in maximizing party power through gerrymandering is packing, where voters from the opposing party are concentrated into a small number of districts. This ensures that the opposition wins those districts overwhelmingly but leaves them with fewer resources and opportunities to compete in other areas. For example, if a state has a significant minority population that tends to vote for the opposing party, gerrymandering can pack these voters into a single district, minimizing their impact on surrounding districts. This not only guarantees a win for the opposition in that packed district but also frees up adjacent districts to be more easily won by the dominant party.

Another critical strategy is cracking, which involves dispersing voters from the opposing party across multiple districts to prevent them from achieving a majority in any single district. By diluting their voting power, the dominant party can secure victories in several districts where the opposition might otherwise have been competitive. For instance, if a city has a strong base of opposition voters, gerrymandering can split the city into multiple districts, ensuring that the opposition’s votes are spread too thin to win in any of them. This tactic effectively neutralizes the opposition’s strength and maximizes the dominant party’s chances of winning.

Strategic boundary redrawing also involves creating safe seats for incumbent candidates while making contested districts more favorable to the dominant party. By analyzing voting patterns and demographic data, party leaders can design districts that include strongholds of their own supporters while excluding areas with strong opposition. This ensures that incumbents face minimal risk of losing their seats, allowing the party to focus resources on competitive districts. Additionally, gerrymandering can be used to protect vulnerable incumbents by redrawing their districts to include more favorable voters, further securing the party’s hold on power.

Finally, gerrymandering allows parties to anticipate and counteract demographic shifts that might threaten their dominance. As populations change due to migration, aging, or other factors, parties can adjust district boundaries to maintain their advantage. For example, if a region is experiencing an influx of younger, more progressive voters, gerrymandering can be used to offset this shift by redrawing districts to include more conservative areas. This proactive approach ensures that the party remains in control, even as the electorate evolves. By strategically redrawing boundaries, parties can consolidate their voter bases and secure long-term electoral advantages, cementing their power in the political landscape.

The Dark Origins: Which Political Party Founded the KKK?

You may want to see also

Diluting Opposition Votes: Spreading opposing voters thinly to minimize their impact on elections

Political gerrymandering often involves the strategic manipulation of district boundaries to dilute opposition votes, ensuring that the opposing party's supporters are spread thinly across multiple districts. This tactic minimizes their ability to win a majority in any single district, thereby reducing their overall electoral impact. By carefully redrawing district lines, the party in power can effectively neutralize the influence of opposition voters, even if they constitute a significant portion of the electorate. This practice is particularly effective in regions where the opposition’s voter base is geographically concentrated, as it disperses their strength and prevents them from consolidating power in key areas.

One method of diluting opposition votes is through a process known as "cracking." This involves splitting a concentrated bloc of opposition voters into several districts where they become a minority in each. For example, if a city has a strong Democratic voter base, gerrymandering might divide the city into multiple districts, each paired with heavily Republican suburban or rural areas. As a result, Democratic voters are outnumbered in every district, and their collective influence is diminished. This ensures that even if the opposition party has substantial support, they are unable to translate that support into electoral victories.

Another approach is "packing," which involves cramming as many opposition voters as possible into a single district. While this guarantees a win for the opposition in that district, it comes at the cost of weakening their presence in surrounding areas. By packing opposition voters into one district, the party in power can secure comfortable majorities in the remaining districts. This strategy not only dilutes the opposition’s overall impact but also wastes their votes, as any votes cast beyond the threshold needed to win a district do not contribute to additional seats.

Geographic dispersion plays a critical role in diluting opposition votes. By spreading opposition voters across vast, often rural districts, gerrymandering ensures that their population density is too low to sway election outcomes. This is particularly effective in states with diverse geographic landscapes, where urban opposition voters can be paired with large, sparsely populated rural areas. The result is that opposition voters are effectively silenced, as their numbers are insufficient to challenge the majority in any given district.

Finally, the dilution of opposition votes is often achieved through the creation of oddly shaped districts that prioritize partisan advantage over logical geographic boundaries. These "Frankenstein" districts may snake through multiple counties or cities, connecting disparate areas solely to achieve a specific voter composition. Such districts are designed to maximize the influence of the party in power while marginalizing opposition voters. This manipulation of boundaries is a direct and intentional effort to undermine the democratic principle of "one person, one vote" by ensuring that opposition votes are spread too thinly to matter.

In summary, diluting opposition votes through gerrymandering is a calculated strategy to minimize the electoral impact of opposing voters. By employing tactics such as cracking, packing, geographic dispersion, and the creation of irregularly shaped districts, the party in power can effectively neutralize the opposition’s ability to win elections. This practice undermines fair representation and highlights the need for reforms to ensure that electoral districts are drawn in a manner that reflects the true will of the electorate.

Are Political Parties Truly Policy-Making Institutions? Exploring Their Role

You may want to see also

Protecting Incumbents: Crafting districts to ensure current officeholders face weaker challenges

Political gerrymandering often involves the strategic manipulation of district boundaries to protect incumbents, ensuring they face weaker challenges in elections. This practice is rooted in the desire of political parties to maintain power by minimizing the risk of their current officeholders losing their seats. By crafting districts that favor incumbents, parties can solidify their control over legislative bodies and reduce the likelihood of electoral upsets. This tactic is particularly prevalent in systems where redistricting is controlled by the party in power, allowing them to draw lines that benefit their own members.

One key method of protecting incumbents is through the creation of "safe seats," where the demographic and political composition of a district is heavily skewed in favor of the incumbent's party. This is achieved by packing districts with voters who are highly likely to support the incumbent, often based on party affiliation, voting history, or socioeconomic factors. For example, a district might be drawn to include a high concentration of urban, liberal voters to protect a Democratic incumbent or rural, conservative voters to shield a Republican officeholder. By ensuring a strong base of support, incumbents can avoid competitive races and focus on other priorities, such as fundraising or legislative work.

Another strategy involves "cracking" opposition voters across multiple districts to dilute their influence. Instead of allowing a concentrated group of opposition voters to form a competitive district, gerrymandering spreads them thinly across several districts, ensuring they cannot achieve a majority in any one area. This effectively neutralizes their voting power and reduces the likelihood of a strong challenger emerging. For instance, a group of voters who consistently support a particular party might be divided among several districts where their numbers are insufficient to sway the outcome, thereby protecting the incumbents in those districts.

Incumbents are also protected through the practice of "incumbent pairing," where district lines are drawn to avoid pitting two incumbents from the same party against each other in a primary election. This is particularly important in cases where population shifts necessitate the elimination of a district. By carefully redrawing boundaries, redistricting authorities can ensure that incumbents are placed in districts where they are likely to win, rather than forcing them into a competitive race against a fellow party member. This preserves the party's overall representation and avoids internal conflicts.

Additionally, gerrymandering often involves the use of geographic and demographic data to create districts that are seemingly competitive on paper but are, in reality, designed to favor the incumbent. This can be achieved by including areas with strong incumbent support while excluding regions where opposition is strong. For example, a district might be drawn to include neighborhoods with high turnout for the incumbent's party while excluding areas with active opposition groups. This creates the illusion of competition while ensuring the incumbent maintains a significant advantage.

In conclusion, protecting incumbents through gerrymandering is a deliberate and strategic process aimed at minimizing electoral risks for current officeholders. By crafting districts that favor incumbents, political parties can maintain their grip on power and reduce the likelihood of losing seats. While this practice can provide stability for incumbents, it often comes at the expense of fair representation and competitive elections, raising significant concerns about the integrity of democratic processes. Understanding these tactics is crucial for addressing the broader implications of gerrymandering on political systems.

Joseph McCarthy's Political Party: Uncovering His Affiliation and Legacy

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Racial or Group Targeting: Manipulating districts to favor or suppress specific demographic groups

Political gerrymandering often involves racial or group targeting, a practice where district lines are manipulated to favor or suppress specific demographic groups, particularly racial or ethnic minorities. This strategy is employed to dilute the voting power of certain communities or to concentrate their influence in a limited number of districts, thereby ensuring political outcomes that align with the interests of the party in control of the redistricting process. By strategically drawing district boundaries, those in power can either pack minority voters into a single district, reducing their impact across multiple districts, or crack them by dispersing them across several districts to diminish their collective voting strength.

One common method of racial targeting is packing, where minority voters are concentrated into a small number of districts, often creating a majority-minority district. While this might seem beneficial, it effectively limits the influence of these voters to only those districts, preventing them from swaying elections in other areas. For example, if a state has a significant African American population, gerrymandering might pack them into one or two districts, ensuring those districts elect minority representatives but minimizing their ability to influence surrounding districts. This tactic ensures that the majority party retains control in the remaining districts, solidifying their political dominance.

Conversely, cracking involves dispersing minority voters across multiple districts to dilute their voting power. By spreading these voters thinly, the majority party can ensure that no single district has enough minority voters to elect their preferred candidate. This method is particularly effective in areas where minority populations are growing but not yet large enough to dominate a district. For instance, Latino voters in a rapidly diversifying region might be cracked across several districts, preventing them from forming a majority in any one district and thus maintaining the status quo for the majority party.

Racial targeting in gerrymandering is not only a tool for political gain but also a means to perpetuate systemic inequalities. By suppressing the voting power of minority groups, this practice undermines their ability to elect representatives who reflect their interests and address their specific needs. This disenfranchisement can lead to policies that disproportionately harm these communities, perpetuating cycles of poverty, lack of access to quality education, and inadequate healthcare. Furthermore, racial gerrymandering often violates the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which prohibits the dilution of minority voting strength, though legal challenges to such practices can be complex and time-consuming.

To combat racial targeting in gerrymandering, advocacy groups and legal organizations have pushed for reforms such as independent redistricting commissions, stricter legal standards, and increased transparency in the redistricting process. These measures aim to remove partisan influence from district drawing and ensure that maps are fair and representative of the population. Additionally, technological advancements, such as algorithmic redistricting tools, offer potential solutions by creating more objective and unbiased district boundaries. However, the effectiveness of these reforms depends on political will and enforcement, as those in power often resist changes that could diminish their control.

In conclusion, racial or group targeting in gerrymandering is a deliberate and harmful practice that manipulates district boundaries to favor or suppress specific demographic groups. Whether through packing or cracking, this strategy undermines democratic principles by disenfranchising minority voters and perpetuating political and social inequalities. Addressing this issue requires systemic reforms and a commitment to creating a more equitable and representative political system.

Exploring Nations That Restrict the Number of Political Parties

You may want to see also

Securing Funding/Support: Designing districts to appeal to donors or key political allies

Political gerrymandering often involves designing districts to secure funding and support from donors or key political allies. This strategy is crucial for maintaining financial stability and building coalitions that can sustain political campaigns and initiatives. By carefully crafting district boundaries, political parties can create environments where their messaging resonates strongly with influential donors and allies, ensuring a steady flow of resources. This approach leverages demographic and socioeconomic data to identify areas where potential supporters are concentrated, allowing for targeted appeals that align with their interests and values.

One effective method for securing funding through gerrymandering is to consolidate wealthy or high-income neighborhoods into specific districts. These areas often house individuals and corporations with significant financial resources who are willing to invest in political campaigns. By drawing district lines to include these neighborhoods, politicians can position themselves as representatives of these affluent communities, making it easier to solicit donations. Additionally, tailoring policy platforms to address the concerns of these donors, such as tax policies or business regulations, further solidifies their support and encourages continued investment.

Another tactic involves designing districts to appeal to key political allies, such as labor unions, industry groups, or advocacy organizations. For example, districts can be drawn to include large concentrations of union members, ensuring that candidates who support labor rights and collective bargaining are favored. Similarly, districts with significant agricultural or manufacturing sectors can be crafted to attract support from industry associations. By aligning district boundaries with the geographic distribution of these allies, politicians can secure endorsements, volunteer networks, and financial backing from organizations that share their policy priorities.

Geographic targeting also plays a critical role in appealing to donors and allies. Districts can be designed to encompass areas where political action committees (PACs) or special interest groups have a strong presence. For instance, districts in urban centers might be tailored to attract support from progressive organizations, while rural districts could be drawn to appeal to conservative or agricultural interests. This strategic alignment ensures that candidates can tap into established networks of support, leveraging the resources and influence of these groups to bolster their campaigns.

Finally, gerrymandering can be used to dilute opposition and minimize the influence of competing donors or allies in neighboring districts. By packing opponents into a few districts, politicians can reduce their ability to challenge incumbents or fund rival campaigns. This not only secures support within the targeted district but also weakens potential adversaries, creating a more favorable landscape for fundraising and coalition-building. Ultimately, designing districts to appeal to donors and key political allies is a calculated strategy that ensures financial stability and strengthens political alliances, reinforcing the power of those who control the redistricting process.

Why Political Bots Thrive: Manipulating Public Opinion in the Digital Age

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political gerrymandering is the practice of drawing electoral district boundaries in a way that favors one political party or group over another, often by concentrating voters from the opposing party into a few districts or diluting their influence across many districts.

Politicians engage in gerrymandering to secure or maintain political power by creating districts that are more likely to elect candidates from their own party, thereby increasing their representation in legislative bodies and influencing policy-making.

Gerrymandering can dilute the voting power of certain groups, reduce competitive elections, and lead to unrepresentative outcomes where the party in control of redistricting wins more seats than their overall vote share would suggest, undermining democratic principles and voter confidence.