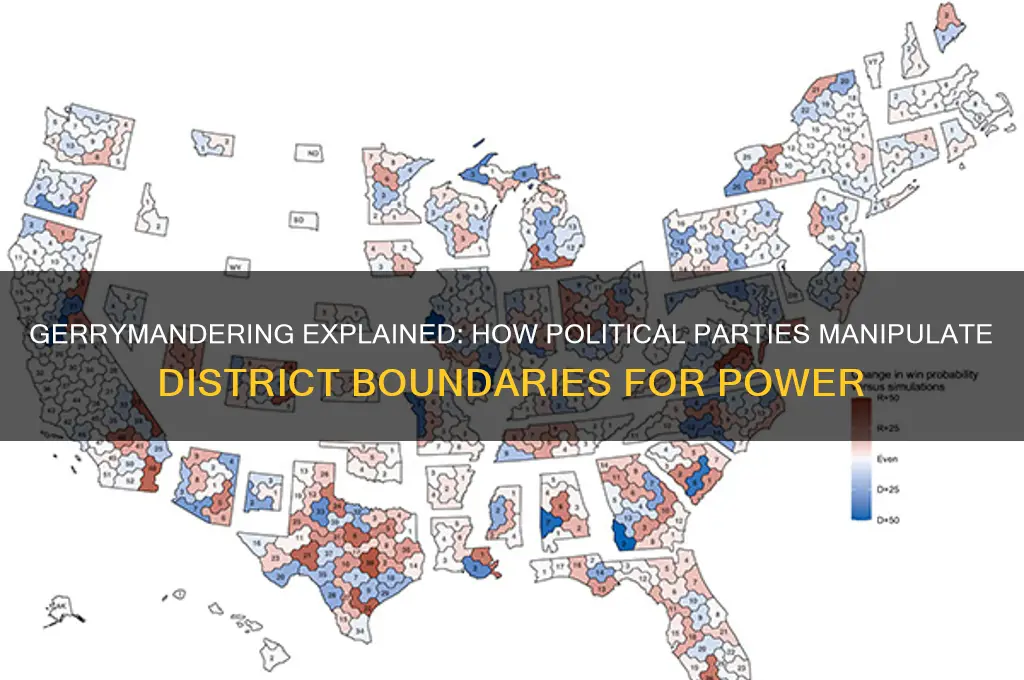

Gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating electoral district boundaries for political advantage, is a contentious strategy employed by political parties to secure or maintain power. By redrawing district lines to concentrate supporters or dilute opponents' voting strength, parties can effectively skew election outcomes in their favor, often regardless of the overall popular vote. This tactic undermines democratic principles by prioritizing partisan interests over fair representation, leading to distorted political landscapes and diminished voter influence. While gerrymandering can provide short-term gains for the party in control, it often fuels polarization, erodes public trust in the electoral process, and perpetuates unequal political power. Understanding why parties engage in this practice requires examining the interplay of political ambition, institutional incentives, and the desire to consolidate control in an increasingly competitive political environment.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Partisan Advantage | To maximize the number of seats for their party by concentrating opponents' voters into fewer districts. |

| Incumbency Protection | To draw district lines that favor incumbent politicians, ensuring their re-election. |

| Dilution of Minority Votes | To reduce the influence of minority groups by splitting their voting power across multiple districts. |

| Strategic Packing | To "pack" opposition voters into a few districts, minimizing their impact in other areas. |

| Cracking Opposition | To "crack" opposition voters across multiple districts, diluting their voting power. |

| Preserving Ideological Homogeneity | To create districts with voters who share similar ideologies, ensuring consistent support for the party. |

| Reducing Competition | To minimize competitive races by creating safe seats for their candidates. |

| State Legislative Control | To maintain control over state legislatures, which often redraw district maps. |

| Federal Representation Influence | To secure more favorable representation in the U.S. House of Representatives. |

| Long-Term Political Dominance | To establish long-term political dominance by locking in favorable district boundaries. |

| Response to Demographic Shifts | To counteract demographic changes that may threaten the party's electoral prospects. |

| Legal Loopholes Exploitation | To exploit legal ambiguities or lack of strict anti-gerrymandering laws to redraw districts favorably. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Maximizing Party Seats: Drawing district lines to ensure more wins with fewer overall votes

- Diluting Opponent Votes: Spreading opposition voters across multiple districts to reduce their impact

- Protecting Incumbents: Crafting safe districts to guarantee re-election for current officeholders

- Racial or Group Targeting: Manipulating boundaries to marginalize or empower specific demographic groups

- Strategic Resource Allocation: Concentrating party resources in winnable districts to optimize campaign efficiency

Maximizing Party Seats: Drawing district lines to ensure more wins with fewer overall votes

Political parties often engage in gerrymandering to maximize their representation in legislative bodies, even if it means winning more seats with fewer overall votes. This practice involves strategically redrawing district lines to concentrate opposition voters into a few districts while diluting their influence across others. By doing so, a party can secure a disproportionate number of seats relative to their statewide vote share. For instance, in the 2012 U.S. House elections, North Carolina Democrats won 51% of the statewide vote but secured only 4 out of 13 congressional seats due to Republican-drawn district maps.

To achieve this, parties employ two primary tactics: cracking and packing. Cracking involves splitting opposition voters across multiple districts to ensure they are a minority in each, thus preventing them from winning any seats. Packing, on the other hand, concentrates opposition voters into a few districts where they win by overwhelming margins, effectively wasting their excess votes. For example, in Ohio’s 2018 congressional elections, Republicans won 52% of the statewide vote but secured 75% of the seats by packing Democratic voters into four urban districts.

The mathematical precision behind this strategy is striking. Suppose a state has 10 districts and Party A wins 55% of the statewide vote. Without gerrymandering, Party A might win 6 seats. However, by cracking and packing, they can secure 8 seats. This is achieved by ensuring Party A wins 55% in 8 districts and loses by large margins in the remaining 2, where opposition votes are concentrated. The result? Party A controls 80% of the seats with just 55% of the vote.

Critics argue this undermines democratic principles, as it distorts the principle of "one person, one vote." However, proponents defend it as a legitimate strategy within the rules of the game. To combat this, some states have adopted independent redistricting commissions. For instance, California’s Citizens Redistricting Commission, established in 2010, has led to more competitive districts and a closer alignment between vote share and seat share.

Practical tips for understanding gerrymandering include examining district shapes for irregularities—often a telltale sign of manipulation. Tools like the efficiency gap, which measures wasted votes, can quantify the extent of gerrymandering. For instance, an efficiency gap of 7% suggests one party’s votes are being systematically underutilized. By focusing on these metrics and advocating for transparent redistricting processes, voters can push back against this practice and ensure fairer representation.

Discover Your Political Age: Unveiling Ideological Generations and Beliefs

You may want to see also

Diluting Opponent Votes: Spreading opposition voters across multiple districts to reduce their impact

One of the most insidious tactics in the gerrymandering playbook is the dilution of opponent votes. This strategy involves spreading opposition voters thinly across multiple districts, effectively drowning their collective voice in a sea of majority support for the incumbent party. Imagine a city where 60% of voters lean Democratic, concentrated in a few neighborhoods. By carving these neighborhoods into several districts dominated by Republican-leaning suburbs, the Democratic vote is fractured. Each district now has a Republican majority, despite the overall Democratic lean. This mathematical manipulation ensures the opposition’s votes are wasted, as they fail to secure a single seat despite their substantial numbers.

To execute this strategy, mapmakers follow a precise process. First, they identify clusters of opposition voters through detailed demographic and voting data. Next, they dissect these clusters, assigning small portions to multiple districts. The key is to avoid creating a single district where the opposition constitutes a majority. For instance, in North Carolina’s 2016 redistricting, Democratic voters in urban areas like Charlotte were split into surrounding Republican-leaning districts. This fragmentation resulted in Democrats winning only three out of 13 congressional seats, despite earning nearly half of the statewide vote. The takeaway? Dilution is a surgical strike against electoral fairness, turning demographic strength into political weakness.

Critics argue that this practice undermines democracy by distorting representation. Proponents, however, defend it as a legitimate tool to secure political stability. Yet, the ethical and practical implications are undeniable. When opposition votes are diluted, marginalized communities often bear the brunt, as their collective interests are sidelined. For example, in states like Wisconsin, urban minority voters have been systematically dispersed, reducing their influence on issues like education funding and criminal justice reform. This isn’t just about winning elections—it’s about silencing voices that challenge the status quo.

To combat this tactic, activists and reformers advocate for independent redistricting commissions and stricter legal standards. In 2019, Michigan voters approved a ballot initiative transferring redistricting power from the legislature to an independent body, significantly reducing opportunities for dilution. Similarly, court cases like *Rucho v. Common Cause* (2019) highlight the need for federal intervention, though the Supreme Court ruled that gerrymandering claims are nonjusticiable. Practical tips for citizens include engaging in local redistricting processes, supporting transparency initiatives, and leveraging technology to identify gerrymandered maps. While dilution remains a potent weapon, awareness and action can blunt its edge.

Mastering Political Party Adjustments in Florida: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Protecting Incumbents: Crafting safe districts to guarantee re-election for current officeholders

One of the most insidious yet effective strategies in political gerrymandering is the deliberate crafting of safe districts to protect incumbents. By redrawing district boundaries to concentrate supporters and dilute opposition, parties create electoral fortresses where their current officeholders face minimal risk of defeat. This tactic not only secures re-election for individual politicians but also solidifies party control over legislative bodies. For example, in 2012, Pennsylvania’s Republican-controlled legislature redrew congressional maps to pack Democratic voters into fewer districts, ensuring GOP incumbents in the remaining districts faced little competition. This manipulation highlights how gerrymandering can transform democracy into a game of predetermined outcomes.

To understand the mechanics, consider the process as a three-step formula: *Identify, Concentrate, and Isolate*. First, identify areas of strong party support and opposition. Second, concentrate opposition voters into a limited number of districts, ensuring those seats are overwhelmingly favorable to the opposing party. Third, isolate the remaining districts to create safe havens for incumbents. This method is particularly effective in states with large urban centers, where densely populated Democratic areas can be packed into a few districts, leaving surrounding areas safely Republican. The result? Incumbents enjoy re-election rates often exceeding 90%, even in highly polarized political climates.

Critics argue that this practice undermines democratic principles by reducing electoral competition and voter choice. However, proponents counter that it fosters stability and allows incumbents to focus on governance rather than constant campaigning. Yet, this stability comes at a cost: it disconnects representatives from the need to appeal to a broad electorate, fostering extremism and partisan gridlock. For instance, a study by the Brennan Center found that gerrymandered districts are 20% less likely to change hands, even in wave election years. This lack of turnover stifles fresh ideas and limits accountability, as incumbents face little pressure to address constituent concerns.

Practical tips for spotting gerrymandered safe districts include examining district shapes for irregularity, analyzing voter registration data for partisan imbalance, and tracking re-election rates over time. Tools like spatial analysis software and publicly available census data can help identify districts where boundaries have been manipulated to favor incumbents. For activists and voters, challenging these practices requires legal action, advocacy for independent redistricting commissions, and public education on the impact of gerrymandering. While reform is challenging, states like California and Michigan have successfully implemented nonpartisan redistricting, proving change is possible.

In conclusion, crafting safe districts to protect incumbents is a strategic but controversial use of gerrymandering. While it ensures party loyalty and reduces electoral uncertainty, it distorts representation and diminishes democratic competition. By understanding the methods and consequences of this practice, voters and advocates can work toward fairer redistricting processes that prioritize communities over incumbents. The fight against gerrymandering is not just about redrawing lines—it’s about reclaiming the integrity of the electoral process.

William Joseph Simmons' Political Party: Uncovering His Affiliation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Racial or Group Targeting: Manipulating boundaries to marginalize or empower specific demographic groups

One of the most insidious forms of gerrymandering involves manipulating district boundaries to dilute or concentrate the voting power of specific racial or demographic groups. This tactic, often driven by a desire to maintain or alter political dominance, can have profound and lasting impacts on representation and equality. For instance, in the United States, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was enacted to combat such practices, yet modern examples like North Carolina’s 2016 redistricting show how racial gerrymandering persists. In this case, the Supreme Court struck down districts that were drawn to pack African American voters into a few districts, effectively minimizing their influence in others.

To understand the mechanics, consider this step-by-step breakdown: First, identify the target group—whether racial, ethnic, or another demographic. Second, analyze voting patterns to determine their political leanings. Third, redraw boundaries to either pack them into a single district, where their votes exceed what’s needed to elect a candidate, or crack them across multiple districts, diluting their collective impact. For example, in Texas, Latino voters have been cracked across districts to prevent them from forming a majority in any one area, thus limiting their ability to elect representatives of their choice.

The ethical and practical implications of such targeting are stark. Marginalizing groups through gerrymandering undermines democratic principles by silencing voices that should be heard. Conversely, empowering groups by creating majority-minority districts can enhance representation but may also lead to accusations of tokenism or segregation. A comparative analysis of states like Georgia and Alabama reveals how the same tactic can yield different outcomes depending on the intent and execution. In Georgia, efforts to create majority-minority districts have increased Black representation, while in Alabama, similar attempts were deemed unconstitutional for their racial motivations.

For activists and policymakers, combating racial gerrymandering requires vigilance and strategic action. Start by advocating for independent redistricting commissions to remove partisan bias from the process. Leverage data analytics to identify patterns of discrimination in proposed maps. Engage in legal challenges under the Voting Rights Act or the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. Practical tips include organizing community education campaigns to raise awareness and mobilizing voters to participate in local redistricting hearings. By addressing this issue head-on, we can work toward a more equitable and representative political system.

Exploring Common Political Cultures: Beliefs, Values, and Practices Shaping Societies

You may want to see also

Strategic Resource Allocation: Concentrating party resources in winnable districts to optimize campaign efficiency

Political parties often engage in gerrymandering to maximize their electoral advantage, and one key strategy within this practice is strategic resource allocation. By concentrating party resources in winnable districts, parties can optimize campaign efficiency, ensuring that every dollar, volunteer hour, and campaign event yields the highest possible return. This approach is not just about redrawing district lines but about deploying resources where they will have the most impact.

Consider the mechanics of this strategy. Parties analyze demographic data, voting histories, and polling trends to identify districts where their candidate has a strong chance of winning. These "winnable" districts become the focal points for resource allocation. For instance, a party might funnel 70% of its campaign budget into 30% of its targeted districts, rather than spreading resources thinly across all contested areas. This concentration allows for more effective messaging, higher-quality advertising, and more frequent voter outreach, increasing the likelihood of victory in those districts.

However, this approach is not without risks. Over-concentrating resources can leave other districts underfunded and vulnerable to opposition gains. Parties must strike a balance, using data analytics to identify the tipping point where additional investment in a district yields diminishing returns. For example, a party might allocate 60% of its resources to safe and likely winnable districts, reserving the remaining 40% for competitive districts where a surge in funding could tip the scales. This data-driven approach ensures that resources are not wasted on districts that are either too safe or too far out of reach.

A practical example of this strategy can be seen in the 2018 U.S. midterm elections, where the Democratic Party focused heavily on suburban districts with shifting demographics. By allocating resources to these winnable districts, they successfully flipped several seats, contributing to their majority in the House of Representatives. Conversely, spreading resources too thinly across rural and solidly Republican districts might have diluted their impact, resulting in fewer overall victories.

In implementing strategic resource allocation, parties should follow these steps: first, conduct a thorough analysis of district-level data to identify winnable seats. Second, prioritize these districts for resource allocation, ensuring that funding, staff, and messaging are tailored to local issues and voter preferences. Third, monitor campaign performance in real time, adjusting resource distribution as needed to respond to shifting dynamics. Finally, maintain a contingency fund to address unexpected opportunities or challenges in competitive districts. By following this approach, parties can maximize their efficiency and increase their chances of electoral success.

Why Political Parties Constantly Fuel Anger and Division

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Gerrymandering is the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party over another. Political parties engage in it to consolidate their voter base, dilute the opposition's voting power, and increase their chances of winning elections.

Gerrymandering can skew election results by creating "safe" districts for one party and "packed" or "cracked" districts for the opposition. This often leads to disproportionate representation, where a party wins more seats than their overall vote share would suggest.

While gerrymandering is legal in many places, it is subject to certain restrictions. Courts in some countries, like the U.S., have ruled that extreme partisan or racial gerrymandering violates constitutional rights, though enforcement remains inconsistent.

Political parties prioritize gerrymandering because it provides a strategic advantage in maintaining or gaining power. It allows them to secure more seats with fewer votes, ensuring long-term control over legislative bodies and policy-making.

Gerrymandering undermines democratic principles by distorting voter representation, reducing competition in elections, and polarizing politics. It can lead to voter disillusionment, decreased accountability of elected officials, and a weakened political system.