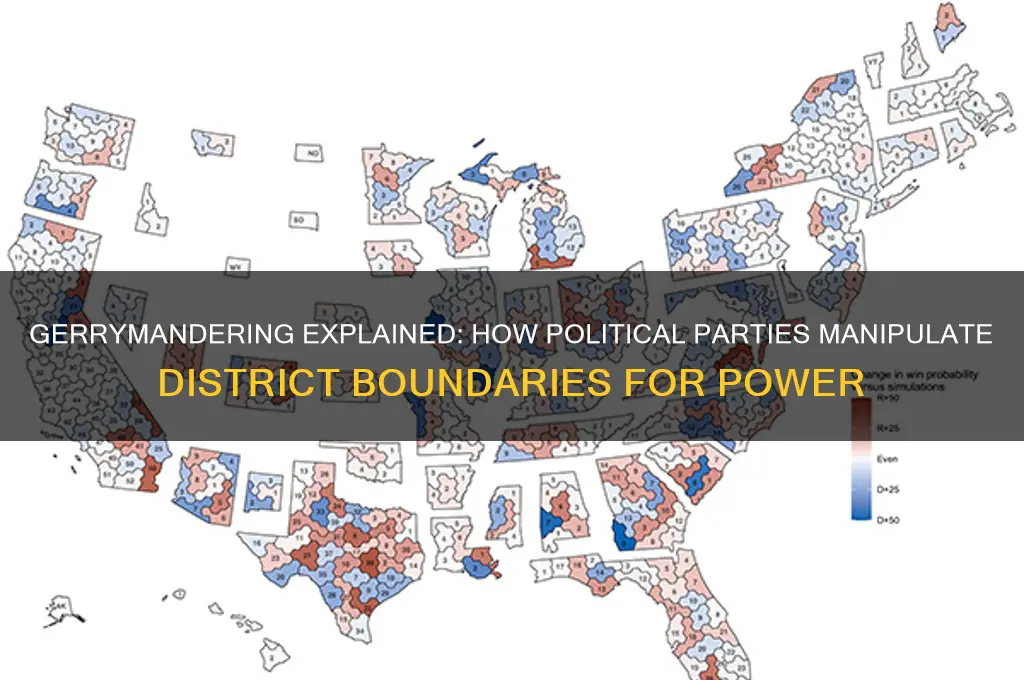

Gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating electoral district boundaries to favor a particular political party, is a contentious strategy employed by political parties to secure and maintain power. By redrawing district lines to concentrate or disperse voter groups, parties can effectively dilute the influence of opposing voters or create safe seats for their candidates. This tactic often results in oddly shaped districts that prioritize partisan advantage over geographic or community coherence. While gerrymandering can provide short-term electoral gains, it undermines democratic principles by distorting representation and reducing competitive elections, ultimately eroding public trust in the political system.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Maintain Political Power | Ensures incumbents or their party retain control by manipulating district boundaries. |

| Dilute Opposition Votes | Concentrates opposition voters into fewer districts to reduce their electoral impact. |

| Protect Incumbents | Creates "safe seats" for existing politicians, reducing the risk of losing reelection. |

| Favor Specific Demographics | Targets or excludes certain racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic groups to influence outcomes. |

| Strategic Resource Allocation | Directs funding and policy focus to districts that benefit the party’s agenda. |

| Suppress Minority Representation | Limits the ability of minority groups to elect representatives of their choice. |

| Exploit Geographic Clustering | Takes advantage of where supporters or opponents are concentrated to maximize advantage. |

| Reduce Competitive Elections | Minimizes the number of swing districts to solidify party dominance. |

| Manipulate Electoral Maps | Uses advanced data and technology to draw boundaries that favor the party’s interests. |

| Long-Term Strategic Advantage | Ensures sustained political control beyond a single election cycle. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Securing Re-election: Parties manipulate districts to favor incumbents, ensuring continued political power

- Diluting Opposition Votes: Spreading opposing voters thinly to reduce their electoral impact

- Protecting Incumbents: Creating safe seats to shield party members from competitive elections

- Racial/Ethnic Control: Drawing lines to marginalize or consolidate minority voting power

- Partisan Advantage: Maximizing seats for one party despite potentially losing the popular vote

Securing Re-election: Parties manipulate districts to favor incumbents, ensuring continued political power

Political parties often engage in gerrymandering to secure re-election by manipulating district boundaries to favor incumbents. This practice ensures that sitting politicians maintain their seats, solidifying their party’s grip on power. By concentrating opposition voters into a few districts or diluting their influence across many, parties create "safe" seats where incumbents face minimal competition. For example, in North Carolina’s 2016 redistricting, Republicans drew maps that packed Democratic voters into just three districts, allowing them to win 10 out of 13 seats despite earning only 53% of the statewide vote. This strategic redrawing of lines highlights how gerrymandering is a tool to entrench political power rather than reflect the will of the electorate.

To understand how this works, consider the mechanics of gerrymandering. Parties use voter data, including party affiliation, voting history, and demographic information, to craft districts that maximize their advantage. Incumbents benefit from this process because it minimizes the risk of losing their seats. For instance, a Republican incumbent in a historically competitive district might see their district redrawn to include more conservative-leaning areas, effectively neutralizing potential challenges from Democratic candidates. This manipulation not only secures re-election but also discourages strong challengers from running, as the odds of victory become overwhelmingly stacked against them.

The consequences of this practice extend beyond individual races. Gerrymandering to favor incumbents undermines democratic principles by reducing electoral competition. When districts are drawn to ensure one-party dominance, general elections become mere formalities, and the real contest shifts to primary elections. This shift often pushes incumbents to adopt more extreme positions to appeal to their party’s base, polarizing politics further. For example, in states like Texas and Maryland, gerrymandered districts have contributed to the rise of hyper-partisan representatives who prioritize party loyalty over bipartisan solutions.

Despite its effectiveness, gerrymandering to secure re-election is not without risks. Courts and voters are increasingly challenging these practices, citing violations of constitutional rights and fair representation. In 2019, the Supreme Court ruled in *Rucho v. Common Cause* that federal courts could not intervene in partisan gerrymandering cases, but state-level efforts have gained traction. States like Michigan and Colorado have adopted independent redistricting commissions to draw fairer maps, reducing the ability of parties to manipulate districts for incumbents. These reforms demonstrate that while gerrymandering is a powerful tool, it is not invincible.

For those seeking to combat this practice, practical steps include advocating for independent redistricting processes, supporting legal challenges to gerrymandered maps, and engaging in voter education initiatives. By raising awareness of how gerrymandering secures re-election for incumbents, citizens can pressure lawmakers to prioritize fairness over partisan gain. Ultimately, the fight against gerrymandering is a fight for a more representative democracy—one where districts reflect communities, not political strategies.

Unveiling the Power Players: Who Funds Major Political Campaigns?

You may want to see also

Diluting Opposition Votes: Spreading opposing voters thinly to reduce their electoral impact

One of the most insidious tactics in the gerrymandering playbook is the dilution of opposition votes. Imagine a city where 60% of voters lean Democratic and 40% lean Republican. Instead of drawing districts that reflect this balance, a Republican-controlled legislature might carve the city into multiple districts, ensuring Democratic voters are spread thinly across each. This strategy, known as "cracking," prevents the opposition from achieving a majority in any single district, effectively neutralizing their electoral power. For instance, in North Carolina’s 2010 redistricting, Republican mapmakers dispersed Democratic voters across several districts, turning what should have been competitive races into safe Republican seats.

To execute this strategy, mapmakers follow a precise process. First, they identify areas with high concentrations of opposition voters, often urban centers or minority communities. Next, they divide these areas into multiple districts, ensuring the opposition’s voting power is fragmented. For example, in Ohio, Republican legislators split Cleveland into three congressional districts, diluting Democratic votes and securing Republican victories in all three. This methodical approach requires detailed demographic data and sophisticated mapping software, tools that have become increasingly accessible in the digital age.

The consequences of vote dilution are profound. In states like Wisconsin, gerrymandering has led to a mismatch between the popular vote and legislative representation. Despite Democrats winning a majority of the statewide vote in 2018, Republicans retained control of the state legislature due to carefully drawn district lines. This distortion undermines the principle of "one person, one vote," eroding public trust in the democratic process. Critics argue that such practices disenfranchise voters, particularly minorities, whose political influence is systematically weakened.

However, combating vote dilution is not impossible. Courts have increasingly scrutinized gerrymandered maps, striking down those that violate constitutional principles. In 2019, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court redrew the state’s congressional map after finding it unfairly favored Republicans. Additionally, independent redistricting commissions, as used in California, can reduce partisan manipulation by removing map-drawing authority from legislators. Voters can also advocate for transparency in the redistricting process, demanding public input and data-driven criteria to ensure fairness.

Ultimately, diluting opposition votes through gerrymandering is a calculated assault on democratic representation. By spreading opposing voters thinly, political parties can secure disproportionate power, often at the expense of minority and urban communities. While the practice remains widespread, legal challenges and grassroots efforts offer hope for reform. Understanding this tactic is the first step toward advocating for fairer electoral maps and safeguarding the integrity of our democratic system.

Understanding Teal Clear Politics: A New Paradigm in Governance and Leadership

You may want to see also

Protecting Incumbents: Creating safe seats to shield party members from competitive elections

One of the most strategic yet controversial reasons political parties engage in gerrymandering is to protect their incumbents by crafting safe seats. These districts are meticulously designed to ensure that the party’s sitting representatives face minimal electoral risk, often by packing opposition voters into a few districts while diluting their presence elsewhere. For instance, in North Carolina’s 2016 redistricting, Republican lawmakers drew maps that secured 10 out of 13 congressional seats for their party, despite winning only 53% of the statewide vote. This tactic effectively shields incumbents from competitive elections, allowing them to focus on national or state-level agendas rather than local campaigns.

The process of creating safe seats involves a delicate balance of demographic and geographic manipulation. Party strategists analyze voting patterns, racial composition, and socioeconomic data to draw district lines that maximize their advantage. In Texas, for example, Democratic voters in urban areas like Houston and San Antonio were divided into multiple districts, reducing their influence in statewide elections. This fragmentation ensures that incumbents in neighboring districts face little threat from challengers, even in years when the political tide might otherwise shift against them. The result is a system where reelection becomes almost guaranteed, fostering complacency and reducing accountability to constituents.

Critics argue that this practice undermines democratic principles by distorting representation and stifling competition. When incumbents are insulated from electoral pressure, they may prioritize party loyalty over constituent needs, leading to policies that favor special interests rather than the public good. A 2020 study by the Brennan Center found that only 10% of House races were considered competitive, a stark decline from previous decades. This lack of competition not only diminishes voter engagement but also perpetuates a political class that is increasingly out of touch with the electorate.

To counteract this trend, some states have adopted independent redistricting commissions, tasked with drawing fairer maps free from partisan influence. California’s Citizens Redistricting Commission, established in 2010, has been cited as a model for reducing gerrymandering and increasing electoral competitiveness. However, such reforms face fierce opposition from parties that benefit from the status quo. For voters, staying informed about redistricting processes and advocating for transparency can be powerful tools in combating the entrenchment of incumbents through gerrymandering.

Ultimately, the practice of creating safe seats through gerrymandering highlights a fundamental tension in democratic systems: the balance between party stability and electoral accountability. While protecting incumbents may provide parties with strategic advantages, it comes at the cost of fair representation and vibrant political competition. As redistricting battles continue to unfold across the country, the challenge lies in designing systems that prioritize the voices of voters over the interests of those in power.

Uncovering Ulysses S. Grant's Political Party Affiliation: Republican Roots Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Racial/Ethnic Control: Drawing lines to marginalize or consolidate minority voting power

Gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating electoral district boundaries for political advantage, often intersects with racial and ethnic demographics. One of its most contentious applications is the deliberate drawing of lines to marginalize or consolidate minority voting power. This strategy, rooted in historical and systemic inequalities, aims to dilute the influence of racial and ethnic minorities or, conversely, to pack them into a limited number of districts to minimize their broader electoral impact.

Consider the mechanics of this process. In *cracking*, districts are drawn to disperse minority voters across multiple districts, ensuring they never form a majority in any one area. This effectively silences their collective voice, as their votes are insufficient to sway outcomes in any single district. For example, in North Carolina’s 2010 redistricting, African American voters were spread across several districts, reducing their ability to elect candidates of their choice. Conversely, *packing* involves concentrating minority voters into a few districts, often exceeding the population needed to win, thereby wasting their additional votes and limiting their influence in surrounding areas. Texas’s 2021 redistricting is a case in point, where Latino voters were packed into specific districts, diminishing their impact statewide.

The legal landscape surrounding this issue is complex. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 prohibits racial gerrymandering, but its enforcement has been weakened by Supreme Court decisions like *Shelby County v. Holder* (2013), which struck down key preclearance provisions. Without federal oversight, states have greater latitude to redraw maps that disadvantage minority voters. However, courts have occasionally intervened, as in *Cooper v. Harris* (2017), where the Supreme Court ruled that North Carolina’s redistricting unconstitutionally used race as the predominant factor in drawing district lines.

To combat racial gerrymandering, advocacy groups and policymakers must focus on transparency and public participation in the redistricting process. Independent commissions, rather than state legislatures, can draw fairer maps by prioritizing community integrity over partisan gain. Additionally, leveraging technology, such as open-source mapping tools, can empower citizens to analyze and challenge gerrymandered districts. For instance, the Public Mapping Project’s DistrictBuilder allows users to create and evaluate redistricting plans, fostering greater accountability.

Ultimately, addressing racial and ethnic control in gerrymandering requires a multifaceted approach. It demands legal reforms to strengthen protections under the Voting Rights Act, increased public awareness of the issue, and the adoption of fairer redistricting practices. By dismantling these barriers, minority communities can secure their rightful representation in the democratic process, ensuring their voices are heard and their votes count.

Was the USSR a Political Party? Unraveling Soviet Governance

You may want to see also

Partisan Advantage: Maximizing seats for one party despite potentially losing the popular vote

Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party, is a strategic tool for securing partisan advantage. By meticulously carving up voting maps, parties can maximize their seat count in legislative bodies, even if they fail to win the popular vote. This tactic hinges on concentrating opposition voters into a few districts, a process known as "packing," while dispersing their own supporters across multiple districts, known as "cracking." The result? A party can win more seats with fewer overall votes, effectively subverting the principle of "one person, one vote."

Consider the 2018 midterm elections in North Carolina. Despite Democratic candidates for the U.S. House of Representatives winning 50.5% of the statewide vote, Republicans secured 10 out of 13 congressional seats. This disparity was no accident. Republican-drawn maps strategically packed Democratic voters into three urban districts, ensuring overwhelming victories there, while cracking the remaining Democratic voters across other districts to dilute their influence. This example illustrates how gerrymandering can distort representation, allowing a party to maintain power despite lacking majority support.

The mechanics of this strategy are both precise and deliberate. Advanced data analytics and mapping software enable parties to predict voting patterns with remarkable accuracy. By identifying clusters of opposition voters and drawing district lines to isolate them, parties can minimize the number of competitive districts. This reduces the risk of losing seats and ensures that their own supporters are spread efficiently to win a majority of districts, even if their overall vote share is lower. For instance, in Pennsylvania’s 2012 redistricting, Republicans drew maps that yielded 13 out of 18 congressional seats despite winning only 49% of the statewide vote.

Critics argue that this practice undermines democratic fairness, as it prioritizes party power over voter representation. However, proponents defend it as a legitimate strategy within the rules of the game, emphasizing the importance of strategic planning in politics. To combat this, some states have adopted independent redistricting commissions, tasked with drawing fairer maps. For example, California’s Citizens Redistricting Commission, established in 2010, has been credited with creating more competitive districts and reducing partisan bias.

In practice, addressing gerrymandering requires a multi-pronged approach. Voters can advocate for transparency in the redistricting process, pushing for public hearings and accessible data. Legislators can support reforms like independent commissions or algorithmic mapping tools designed to prioritize compact, contiguous districts. Courts also play a role, as seen in the 2019 *Rucho v. Common Cause* case, where the Supreme Court ruled that federal courts cannot address partisan gerrymandering, leaving the issue to state legislatures and voters. By understanding the mechanics and consequences of partisan gerrymandering, citizens can work toward a more equitable electoral system.

Franklin D. Roosevelt's Political Party: A Democratic Legacy Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Gerrymandering is the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party over another. Political parties engage in it to consolidate their voter base, dilute opposition votes, and secure more seats in legislative bodies, thereby gaining or maintaining political power.

Gerrymandering benefits political parties by creating "safe" districts where their candidates are almost guaranteed to win, while "packing" opposition voters into fewer districts to limit their overall representation. This ensures the party can maximize its electoral gains even if it doesn’t win the popular vote.

While some forms of gerrymandering are illegal (e.g., racial gerrymandering), partisan gerrymandering remains largely legal in the U.S. due to the lack of clear judicial standards to regulate it. Parties continue to engage in it because it is an effective strategy to secure political dominance and protect their interests.

Gerrymandering undermines democracy by distorting representation, reducing competitive elections, and disenfranchising voters. It often leads to polarized politics, as candidates focus on appealing to extreme party bases rather than moderates, and diminishes public trust in the electoral process.