George Washington, the first President of the United States, staunchly opposed the formation of political parties, a stance he articulated in his Farewell Address of 1796. Washington believed that partisan politics would undermine national unity, foster division, and prioritize faction interests over the common good. He argued that political parties would create an environment of bitterness and rivalry, leading to the manipulation of public opinion and the erosion of trust in government. Washington’s concerns stemmed from his experiences during the Revolutionary War and the early years of the Republic, where he witnessed the dangers of factionalism and the potential for parties to exploit regional or ideological differences. His opposition to political parties reflected his vision of a cohesive nation governed by shared principles rather than partisan agendas.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Fear of Factionalism | Washington believed political parties would lead to divisive factions, prioritizing party interests over the nation's well-being. |

| Threat to Unity | He saw parties as a threat to national unity, fostering conflict and undermining the young nation's stability. |

| Corruption and Self-Interest | Washington feared parties would become vehicles for personal gain and corruption, distracting from public service. |

| Weakening of Government | He believed parties could weaken the government by creating gridlock and hindering effective decision-making. |

| Undermining the Constitution | Washington saw parties as potentially undermining the principles and spirit of the Constitution, which aimed for a more unified and collaborative government. |

| Historical Precedent | He was influenced by the negative examples of political factions in ancient Rome and other historical contexts, which often led to instability and decline. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Fear of Faction and Division

George Washington’s opposition to political parties was rooted in his profound fear of faction and division, which he believed would undermine the fragile unity of the fledgling United States. In his Farewell Address, Washington warned that the "baneful effects of the spirit of party" would serve as a "favorable augury" for the nation’s decline. He saw factions as self-interested groups that prioritized their own agendas over the common good, leading to gridlock, acrimony, and ultimately, the erosion of democratic principles. This concern was not abstract; it was born from his experiences during the Revolutionary War and the early years of the republic, where he witnessed how personal rivalries and regional interests could fracture alliances and hinder progress.

To understand Washington’s fear, consider the mechanics of faction. Factions, by their nature, thrive on exclusivity and opposition, fostering an "us vs. them" mentality that stifles compromise. Washington believed this dynamic would distract leaders from addressing pressing national issues, such as economic stability, territorial expansion, and foreign policy. For instance, the emergence of the Federalist and Anti-Federalist factions during the ratification of the Constitution highlighted how ideological divisions could paralyze governance. Washington feared that institutionalizing these divisions through political parties would create a permanent state of conflict, making it impossible to govern effectively.

Washington’s solution was not to suppress dissent but to cultivate a culture of civic virtue and shared purpose. He advocated for leaders who would rise above partisan interests and act as stewards of the nation’s well-being. This approach, however, requires a level of selflessness that is difficult to sustain in a competitive political environment. Modern societies can learn from this by implementing safeguards against extreme polarization, such as ranked-choice voting or bipartisan committees, which encourage collaboration over confrontation. While Washington’s idealism may seem outdated, his warning remains relevant: unchecked faction leads to division, and division weakens the very fabric of democracy.

A practical takeaway from Washington’s stance is the importance of fostering dialogue across ideological lines. Communities and organizations can combat factionalism by creating spaces where diverse perspectives are heard and respected. For example, town hall meetings, cross-party task forces, or educational programs that teach the value of compromise can help bridge divides. Washington’s fear of faction was not just a historical concern but a call to action—a reminder that unity is an ongoing effort, not a given. By prioritizing the common good over partisan victory, we honor his legacy and safeguard the future of democratic governance.

Martin Luther King Jr.'s Political Party Affiliation Explained

You may want to see also

Threat to National Unity

George Washington’s opposition to political parties was rooted in his belief that they would fracture the young nation’s unity. In his Farewell Address, he warned that factions and parties would "distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration," ultimately undermining the common good. This concern was not abstract; it was born from the early Republic’s fragile state, where regional, economic, and ideological differences threatened to splinter the country. Parties, he argued, would exploit these divisions, prioritizing their own interests over national cohesion.

Consider the mechanics of party politics: by design, they encourage competition and opposition. While this can foster debate, it often devolves into zero-sum conflicts where one side’s gain is the other’s loss. In Washington’s era, this dynamic risked exacerbating tensions between the agrarian South and the industrial North, or between Federalist and Anti-Federalist ideologies. Such polarization, he feared, would erode trust in government and foster an "us vs. them" mentality, making compromise—the lifeblood of a functioning democracy—increasingly difficult.

To illustrate, imagine a modern analogy: a sports team where players form cliques, each focused on personal glory rather than team success. The result is chaos, with strategies clashing and morale plummeting. Washington saw political parties as similar cliques, each vying for power at the expense of the nation’s collective goals. He believed this would weaken the country’s ability to respond to crises, whether external threats or internal challenges like economic instability.

Practical steps to mitigate this threat include fostering cross-party collaboration and incentivizing bipartisanship. For instance, legislative rules could require a supermajority for critical decisions, forcing parties to negotiate. Citizens, too, play a role by demanding leaders prioritize unity over partisanship. Washington’s warning remains relevant: in a divided nation, the greatest threat is not external enemies but internal disunity. His vision calls for a political culture that transcends party lines, focusing on shared values and the common good.

Understanding the Blue Party: Political Affiliation and Global Significance

You may want to see also

Corruption and Self-Interest

George Washington's opposition to the formation of political parties was deeply rooted in his concern that such factions would breed corruption and self-interest, undermining the young nation's stability. In his Farewell Address, Washington warned that political parties could become "potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people." This prescient observation highlights how party politics can prioritize personal gain over the common good, creating a system where loyalty to a faction eclipses duty to the nation.

Consider the mechanics of party politics: once formed, parties naturally seek to consolidate power, often at the expense of ethical governance. Members may engage in quid pro quo arrangements, trading favors for support, or exploit legislative loopholes to benefit their constituents disproportionately. For instance, earmarks—specific allocations of funds for pet projects—have historically been used to secure votes, fostering a culture of self-interest rather than principled decision-making. Washington foresaw such practices, understanding that once entrenched, these behaviors would corrode public trust and institutional integrity.

To combat the corrosive effects of party-driven corruption, Washington advocated for a system of independent governance, where leaders made decisions based on merit and national interest rather than partisan loyalty. He believed that elected officials should act as trustees of the people, not as agents of a political machine. This model, though idealistic, offers a practical framework for reducing self-interest: by limiting the influence of party platforms, policymakers can focus on evidence-based solutions rather than ideological posturing. For example, nonpartisan bodies like the Congressional Budget Office demonstrate how impartial analysis can inform policy, free from partisan bias.

However, implementing such a system requires vigilance and structural safeguards. Transparency measures, such as public disclosure of campaign financing and stricter lobbying regulations, can mitigate the influence of special interests. Additionally, term limits could reduce the incentive for politicians to prioritize reelection over effective governance. While these steps may not eliminate self-interest entirely, they can create an environment where public service takes precedence over partisan gain, aligning more closely with Washington's vision of a unified, principled government.

Plymouth Colony's Political Landscape: Governance, Challenges, and Legacy

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$11.43 $26.99

$1.99 $11.95

Weakening of Republican Values

George Washington’s opposition to political parties was rooted in his fear that factionalism would erode the core principles of republican governance. In his Farewell Address, he warned that parties foster "self-created and enthusiastic partisans," prioritizing narrow interests over the common good. This dynamic, he argued, weakens the very foundation of a republic, which relies on civic virtue, unity, and the collective welfare of the citizenry. When factions dominate, the public’s trust in institutions wanes, and the system becomes vulnerable to manipulation and decay.

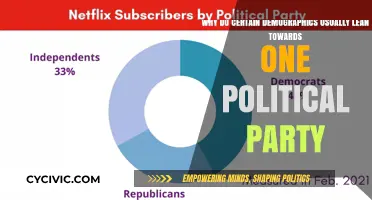

Consider the mechanics of a two-party system: it incentivizes polarization rather than compromise. Parties compete for power by amplifying differences, often at the expense of reasoned debate. This zero-sum game undermines the republican ideal of deliberation, where leaders are expected to act as stewards of the nation, not as agents of their party. For instance, Washington observed how party loyalty could distort policy-making, leading to decisions driven by political expediency rather than long-term national interest. Such practices hollow out the substance of republican governance, replacing principled leadership with partisan brinkmanship.

To illustrate, examine the modern consequences of this dynamic. In contemporary politics, party loyalty frequently trumps constitutional fidelity. Legislators vote along party lines even when it contradicts their stated values, a phenomenon Washington foresaw as corrosive. This erosion of individual judgment weakens the checks and balances essential to a functioning republic. When representatives become mere cogs in a party machine, the system loses its capacity for self-correction, accelerating the decline of republican values.

Practical steps to mitigate this weakening include fostering non-partisan institutions and encouraging cross-party collaboration. For example, implementing ranked-choice voting or open primaries can reduce the stranglehold of party elites. Citizens can also play a role by demanding accountability from their representatives, prioritizing issues over party affiliation. Washington’s warning serves as a call to action: preserving republican values requires vigilance against the centrifugal forces of partisanship. By reclaiming the spirit of unity and public service, we can begin to reverse the damage inflicted by factionalism.

Labour Party vs. US Politics: Ideologies, Policies, and Cultural Differences

You may want to see also

Potential for Foreign Influence

Foreign influence on political parties was a significant concern for George Washington, and his warnings against the dangers of partisanship were deeply rooted in this apprehension. In his Farewell Address, Washington cautioned that political factions could become tools for foreign powers seeking to manipulate American interests. By aligning with a particular party, foreign nations could exploit ideological divisions, offering support or resources to sway policies in their favor. This risk was not hypothetical; Washington had witnessed European powers meddling in the affairs of other nations, using political factions as proxies to advance their agendas. His fear was that such interference would erode American sovereignty and compromise the young nation’s independence.

Consider the mechanics of foreign influence within a two-party system. When parties become entrenched, they often prioritize ideological purity and electoral victory over national unity. This creates vulnerabilities that foreign actors can exploit. For instance, a foreign power might fund campaigns, spread disinformation, or forge alliances with party leaders to tilt policies in their direction. In a polarized environment, these efforts are amplified, as parties may be more willing to accept external support to gain an edge over their opponents. Washington’s concern was prescient: he understood that the rigid structures of political parties could serve as conduits for foreign meddling, undermining the nation’s ability to act in its own best interest.

To mitigate this risk, Washington advocated for a non-partisan approach to governance, emphasizing the importance of leaders making decisions based on the common good rather than party loyalty. This principle is not merely historical but remains relevant today. Modern democracies can learn from Washington’s caution by implementing safeguards against foreign influence, such as stricter campaign finance laws, transparency requirements for political donations, and robust cybersecurity measures to protect against disinformation campaigns. By reducing the avenues through which foreign powers can exploit partisan divisions, nations can preserve their autonomy and strengthen their democratic institutions.

A comparative analysis of nations with strong partisan systems versus those with coalition-based governance reveals the validity of Washington’s concerns. In highly polarized systems, foreign influence often finds fertile ground, as seen in cases where external actors have successfully manipulated election outcomes or policy decisions. Conversely, systems that encourage cross-party collaboration tend to be more resilient to such interference, as decisions are made through consensus rather than partisan rivalry. This suggests that Washington’s opposition to two political parties was not just a rejection of partisanship but a strategic effort to safeguard the nation from external manipulation.

In practical terms, individuals and policymakers can take steps to minimize the potential for foreign influence in partisan politics. First, educate citizens about the risks of foreign meddling and the importance of critical thinking in consuming political information. Second, strengthen legal frameworks to regulate foreign involvement in domestic politics, including stricter oversight of lobbying and campaign contributions. Finally, foster a culture of bipartisanship where national interests take precedence over party agendas. By adopting these measures, societies can honor Washington’s vision of a united, independent nation, free from the corrosive effects of foreign manipulation.

How Political Parties Shape the US Political System

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

George Washington opposed political parties because he believed they would divide the nation, foster conflict, and undermine the common good by prioritizing partisan interests over unity and cooperation.

In his Farewell Address, Washington warned that political parties could create "factions" that would distract from public service, encourage corruption, and threaten the stability of the young republic.

While Washington opposed political parties, he acknowledged their potential inevitability due to differing opinions and interests. However, he hoped Americans would resist their divisive nature.

Washington’s stance initially delayed the formalization of political parties, but his warnings were largely unheeded as the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties emerged during his presidency and afterward.

Washington advocated for a non-partisan approach to governance, emphasizing the importance of virtue, public service, and unity among citizens and leaders to ensure the nation’s success.