Theodore Roosevelt, a former U.S. President and prominent Republican, created his own political party, the Progressive Party (also known as the Bull Moose Party), in 1912 due to his disillusionment with the conservative policies of his successor, William Howard Taft, and the Republican Party's resistance to progressive reforms. Roosevelt, a staunch advocate for social justice, trust-busting, and government regulation, felt that the Republican Party had abandoned its progressive principles and was no longer capable of addressing the pressing issues of the time, such as income inequality, labor rights, and political corruption. After failing to secure the Republican nomination for president in 1912, Roosevelt and his supporters formed the Progressive Party, which became a platform for his ambitious agenda, including women's suffrage, antitrust legislation, and environmental conservation. The party's creation reflected Roosevelt's unwavering commitment to progressive ideals and his belief that a new political movement was necessary to challenge the entrenched interests of both major parties and bring about meaningful change in American society.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Dissatisfaction with GOP Leadership | Roosevelt was disillusioned with the Republican Party's conservative shift under President William Howard Taft, his handpicked successor. |

| Progressive Reform Agenda | He advocated for progressive reforms like trust-busting, labor rights, women's suffrage, and environmental conservation, which the GOP resisted. |

| New Nationalism Platform | Roosevelt's "New Nationalism" vision emphasized federal regulation of corporations, social welfare programs, and strong executive power. |

| 1912 Presidential Election | After losing the GOP nomination to Taft, Roosevelt formed the Progressive Party (Bull Moose Party) to run as a third-party candidate. |

| Grassroots Support | The party gained significant grassroots support from progressives, labor unions, and reform-minded citizens. |

| Election Outcome | Roosevelt finished second in the 1912 election, splitting the Republican vote and handing victory to Democrat Woodrow Wilson. |

| Legacy of the Party | The Progressive Party's platform influenced future U.S. policy, including the New Deal under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. |

Explore related products

$11.99 $17.99

What You'll Learn

- Disillusionment with GOP leadership and policies after Taft's presidency

- Desire to promote progressive reforms and break political stalemate

- Opposition to conservative control of Republican Party

- Belief in direct democracy and citizen empowerment in politics

- Personal ambition to reclaim presidency and shape national agenda

Disillusionment with GOP leadership and policies after Taft's presidency

Theodore Roosevelt's decision to break away from the Republican Party and form the Progressive Party in 1912 was rooted in his profound disillusionment with the GOP's leadership and policies following William Howard Taft's presidency. Roosevelt, a former Republican president himself, had initially supported Taft as his successor, believing they shared a vision for progressive reform. However, Taft's conservative approach to governance, particularly his reluctance to challenge corporate power and his lukewarm support for antitrust measures, created a rift between the two. This divergence in ideology became a catalyst for Roosevelt's eventual departure from the party he once championed.

One of the most striking examples of Taft's departure from Roosevelt's progressive ideals was his handling of antitrust cases. While Roosevelt had aggressively pursued trusts under the Sherman Antitrust Act, Taft's administration took a more cautious approach, often siding with business interests. For instance, Taft's Justice Department filed a lawsuit against U.S. Steel, a move Roosevelt had explicitly advised against, arguing it would harm the economy. This decision not only alienated Roosevelt but also signaled to progressives that Taft was more aligned with corporate elites than with the public interest. Such actions eroded Roosevelt's confidence in Taft's ability to lead the GOP in a direction that prioritized social and economic justice.

Another point of contention was Taft's stance on conservation and natural resource management. Roosevelt, known as the "Conservation President," had set aside millions of acres of public land for future generations. Taft, however, appointed officials who favored exploitation over preservation, leading to increased logging and mining on federal lands. This shift in policy was a direct rebuke to Roosevelt's legacy and further deepened his disillusionment with the GOP's leadership. For progressives, Taft's presidency represented a betrayal of the party's commitment to environmental stewardship, pushing Roosevelt closer to the conclusion that the GOP no longer represented his values.

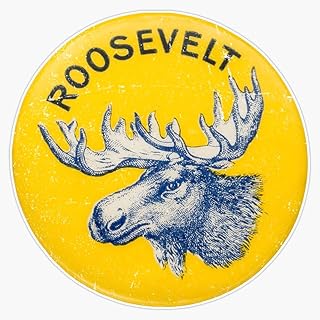

The final straw for Roosevelt came during the 1912 Republican National Convention, where Taft's supporters employed questionable tactics to secure the nomination, effectively sidelining Roosevelt's progressive faction. This political maneuvering convinced Roosevelt that the GOP was no longer a viable vehicle for progressive change. By forming the Progressive Party, also known as the Bull Moose Party, Roosevelt sought to reclaim the progressive agenda and challenge the entrenched interests that had taken control of the Republican Party. His decision was not just a personal reaction to Taft's leadership but a strategic move to realign American politics around the principles of fairness, transparency, and reform.

In retrospect, Roosevelt's disillusionment with the GOP after Taft's presidency was not merely a disagreement over policy but a fundamental clash of visions for America's future. Taft's conservatism and willingness to compromise progressive ideals for political expediency left Roosevelt with no choice but to forge a new path. The creation of the Progressive Party was both a response to Taft's failures and a bold statement about the need for a political movement that prioritized the common good over special interests. This episode underscores the enduring tension within political parties between ideological purity and pragmatic governance, a tension that continues to shape American politics today.

Understanding Political Territory: Boundaries, Power, and Sovereignty Explained

You may want to see also

Desire to promote progressive reforms and break political stalemate

Theodore Roosevelt's decision to form the Progressive Party, often referred to as the "Bull Moose" Party, was driven by a deep-seated desire to advance progressive reforms that he believed were being stifled by the entrenched interests within the Republican Party. By 1912, Roosevelt had grown increasingly frustrated with the conservative leadership of President William Howard Taft, his handpicked successor, who had abandoned many of the progressive policies Roosevelt had championed during his presidency. This ideological rift highlighted a broader issue: the Republican Party was no longer a vehicle for the bold, transformative changes Roosevelt envisioned for the nation.

To understand Roosevelt's motivation, consider the progressive reforms he sought to promote. These included trust-busting, labor rights, consumer protection, and environmental conservation—policies that aimed to address the inequalities and injustices of the Gilded Age. However, the Republican Party's growing alignment with corporate interests created a political stalemate, blocking these reforms from gaining traction. Roosevelt's formation of the Progressive Party was, in essence, a strategic move to break this deadlock. By creating a new political platform, he aimed to galvanize public support for progressive ideas and force both major parties to confront the demands of a changing society.

Roosevelt's approach was both analytical and bold. He recognized that incremental change within the existing party structure was insufficient to address the nation's pressing issues. Instead, he opted for a disruptive strategy, leveraging his immense popularity to challenge the status quo. The Progressive Party's platform, unveiled at the 1912 convention, was a testament to this vision. It called for direct primaries, women's suffrage, social welfare programs, and stricter regulations on corporations—policies that were ahead of their time and directly targeted the root causes of political stagnation.

A comparative analysis of Roosevelt's actions reveals the risks and rewards of such a move. While forming a third party is often seen as a gamble, Roosevelt's decision was grounded in a pragmatic understanding of political dynamics. He knew that by splitting the Republican vote, he might inadvertently aid the Democratic candidate, Woodrow Wilson, which indeed happened in the 1912 election. Yet, Roosevelt prioritized long-term reform over short-term political gains. His willingness to sacrifice immediate success for the sake of advancing progressive ideals underscores the depth of his commitment to breaking the political stalemate.

For those seeking to emulate Roosevelt's strategy in modern contexts, the takeaway is clear: breaking political stalemates often requires bold, unconventional actions. Whether advocating for policy changes within an organization or pushing for systemic reform in government, the key is to identify the barriers to progress and devise strategies that directly confront them. Roosevelt's example teaches us that while third-party movements may not always win elections, they can shift the Overton window, making previously radical ideas mainstream. In this way, his creation of the Progressive Party remains a powerful case study in the pursuit of transformative change.

Identity Politics: When Group Allegiance Becomes a Rational Strategy

You may want to see also

Opposition to conservative control of Republican Party

Theodore Roosevelt's decision to create his own political party, the Progressive Party, in 1912 was rooted in his deep opposition to the conservative control of the Republican Party. By the early 20th century, the GOP had shifted away from the progressive reforms Roosevelt championed during his presidency, aligning instead with corporate interests and reactionary policies. This ideological rift became irreconcilable when the party nominated William Howard Taft, a conservative, as its candidate in 1912, prompting Roosevelt to break away and form a new party that would advance his vision of social and economic justice.

To understand Roosevelt's opposition, consider the conservative policies he found intolerable. The Republican Party under Taft had abandoned antitrust efforts, weakened labor protections, and resisted progressive taxation. For instance, Taft's administration failed to support the regulation of monopolies, a cornerstone of Roosevelt's "Square Deal." This conservative drift alienated Roosevelt and his progressive allies, who saw the party as increasingly captive to Wall Street and big business. Roosevelt's frustration culminated in his famous declaration, "We stand at Armageddon, and we battle for the Lord," during his Progressive Party nomination speech, underscoring his commitment to challenging the GOP's conservative agenda.

Roosevelt's opposition was not merely ideological but also strategic. He recognized that the Republican Party's conservative leadership was out of step with the needs of the American people, particularly the working class and middle class. By forming the Progressive Party, he aimed to create a platform that addressed income inequality, workers' rights, and political corruption. His "New Nationalism" platform called for federal regulation of corporations, social welfare programs, and women's suffrage—policies that the conservative GOP had either ignored or actively opposed. This strategic move was a direct challenge to the party's establishment, forcing a national conversation on progressive reform.

A comparative analysis highlights the stark contrast between Roosevelt's progressive vision and the GOP's conservative stance. While the Republican Party under Taft prioritized business interests and limited government intervention, Roosevelt advocated for an active federal role in addressing societal issues. For example, his proposal for a federal health insurance program and minimum wage laws stood in sharp opposition to the GOP's hands-off approach. This divergence made it impossible for Roosevelt to remain within the party, as its conservative leadership was unwilling to embrace his reformist agenda.

In practical terms, Roosevelt's opposition to conservative control of the Republican Party serves as a lesson in political courage and conviction. His decision to create the Progressive Party, though risky, demonstrated the importance of challenging entrenched power structures when they fail to serve the public good. For those seeking to drive change within their own organizations or communities, Roosevelt's example underscores the need to prioritize principles over party loyalty. While his third-party bid ultimately split the Republican vote and handed the election to Democrat Woodrow Wilson, it also laid the groundwork for future progressive reforms, proving that opposition to conservatism can catalyze meaningful transformation.

Understanding the Non-Partisan Political Party: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$30.95 $16.98

Belief in direct democracy and citizen empowerment in politics

Theodore Roosevelt's decision to create the Progressive Party, often referred to as the "Bull Moose" Party, was deeply rooted in his belief in direct democracy and citizen empowerment. This conviction stemmed from his frustration with the entrenched political machines and the limitations of the two-party system, which he saw as stifling the voice of the people. Direct democracy, in Roosevelt's view, was not just a political tool but a moral imperative to ensure that government remained responsive to the needs and desires of its citizens.

To understand this, consider the steps Roosevelt took to embed direct democracy into his party's platform. He advocated for initiatives, referendums, and recalls—mechanisms that allow citizens to propose laws, approve or reject them, and remove elected officials from office. These tools were revolutionary at the time, shifting power from political elites to the electorate. For instance, in his 1912 campaign, Roosevelt proposed that citizens should have the power to initiate constitutional amendments, a move that would have fundamentally altered the balance of power in favor of the people.

However, implementing direct democracy is not without its challenges. Critics argue that it can lead to uninformed decision-making or be manipulated by special interests. Roosevelt addressed these concerns by emphasizing education and transparency. He believed that an informed citizenry was the cornerstone of effective direct democracy. Practical tips for modern advocates include investing in civic education programs, leveraging technology to disseminate information, and ensuring that ballot measures are written in clear, accessible language. For example, a study by the National Conference of State Legislatures found that states with robust civic education programs saw higher voter turnout and more informed participation in direct democracy initiatives.

Comparatively, Roosevelt's vision aligns with contemporary movements that seek to decentralize political power. The rise of grassroots campaigns and digital platforms has made it easier for citizens to organize and influence policy. Yet, the lessons from Roosevelt's era remain relevant: direct democracy requires vigilance to prevent its misuse. A cautionary tale comes from instances where well-funded groups have dominated ballot initiatives, undermining the very empowerment they were meant to achieve. To mitigate this, modern efforts should focus on campaign finance reform and equitable access to resources for all stakeholders.

In conclusion, Roosevelt's belief in direct democracy and citizen empowerment was not merely a reaction to political gridlock but a forward-thinking vision of governance. By championing tools that give citizens a direct say in their government, he laid the groundwork for a more inclusive and responsive political system. Today, as we grapple with similar challenges, his approach offers both inspiration and practical guidance. For those seeking to empower citizens, the key lies in combining bold innovation with safeguards that ensure the process remains fair and informed.

Arnold Schwarzenegger's Political Party: Republican Roots and Beyond

You may want to see also

Personal ambition to reclaim presidency and shape national agenda

Theodore Roosevelt's decision to create his own political party, the Progressive Party, in 1912 was driven by a potent mix of personal ambition and a vision for transformative national leadership. Having served as president from 1901 to 1909, Roosevelt initially stepped away from politics, endorsing his handpicked successor, William Howard Taft. However, Taft’s conservative policies and reluctance to pursue progressive reforms alienated Roosevelt, who grew increasingly frustrated with the Republican Party’s direction. By 1912, Roosevelt’s desire to reclaim the presidency was not merely about power but about reshaping the nation’s agenda to align with his progressive ideals. His break from the GOP and formation of the Bull Moose Party were bold moves to assert his influence and challenge the status quo.

Roosevelt’s ambition was fueled by his conviction that he alone could champion the progressive cause on a national scale. He believed Taft and the Republican establishment had abandoned the principles of trust-busting, conservation, and social justice that defined his presidency. By creating his own party, Roosevelt sought to bypass the entrenched interests within the GOP and directly appeal to the American people. His campaign platform, known as the New Nationalism, called for federal regulation of corporations, labor rights, and a stronger social safety net—policies he felt were essential for the nation’s future. This was not just a political strategy but a personal mission to reclaim the presidency as a tool for progressive change.

The formation of the Progressive Party was a high-stakes gamble, reflecting Roosevelt’s willingness to risk his political legacy for his ideals. While his third-party candidacy split the Republican vote and inadvertently helped Democrat Woodrow Wilson win the election, it also forced progressive issues into the national spotlight. Roosevelt’s campaign rallies drew massive crowds, demonstrating his enduring popularity and the public’s appetite for reform. His ambition was not merely to win the presidency but to redefine the terms of American politics, positioning progressivism as a viable and necessary alternative to conservatism.

To understand Roosevelt’s motivation, consider the practical steps he took to build the Progressive Party. He leveraged his charisma and reputation to unite disparate reform movements under a single banner. His campaign employed innovative tactics, such as direct appeals to voters through speeches and pamphlets, and emphasized grassroots organizing. Roosevelt’s ability to articulate a clear vision for the nation’s future resonated with millions, even if it ultimately fell short of securing him the presidency. His ambition was a double-edged sword—while it polarized the political landscape, it also left a lasting legacy that influenced future progressive movements.

In retrospect, Roosevelt’s decision to create his own party was a testament to his unyielding ambition and belief in his ability to shape the national agenda. It was a bold, calculated risk driven by his conviction that the presidency was the only platform capable of enacting the sweeping reforms he envisioned. While his immediate goal of reclaiming the White House was unfulfilled, his efforts laid the groundwork for progressive policies that would shape American politics for decades. Roosevelt’s story serves as a cautionary tale about the perils of political division but also as an inspiration for leaders who dare to challenge the system in pursuit of a greater vision.

Michael Bloomberg's Political Affiliation: Democrat, Republican, or Independent?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Theodore Roosevelt created his own political party, the Progressive Party (also known as the Bull Moose Party), in 1912 because he was dissatisfied with the conservative policies of the Republican Party and its nominee, William Howard Taft, who was the incumbent president at the time.

Roosevelt formed the Progressive Party to advocate for progressive reforms, including trust-busting, women’s suffrage, labor rights, and environmental conservation. He believed the Republican Party under Taft had abandoned these principles.

Roosevelt’s decision to run as a third-party candidate split the Republican vote, allowing Democratic nominee Woodrow Wilson to win the presidency with only 42% of the popular vote.

The Progressive Party was nicknamed the "Bull Moose Party" after Roosevelt declared during his campaign, "I’m as strong as a bull moose," following an assassination attempt that failed to stop him from delivering a speech.

Yes, the Progressive Party’s platform influenced future political agendas, including the adoption of progressive reforms by both major parties. While the party disbanded after the 1916 election, its ideas shaped the New Deal era under President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

![Theodore Roosevelt'S Confession of Faith before the Progressive National Convention, August 6, 1912. 1912 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)