In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the removal of people of Japanese ancestry from designated military areas and communities in the United States. This decision, upheld by the Supreme Court in Korematsu v. United States, has been widely criticized as one of the worst Supreme Court rulings in history. The Court's majority opinion justified the order on the grounds of military necessity, arguing that it was not based on racial prejudice but on strategic concerns. However, critics, including dissenting Justices, have highlighted the racial implications and civil rights violations, with some attributing the decision to popular bigotry. The discovery of suppressed evidence further revealed the false premise that Japanese Americans posed a significant threat, leading to the voiding of Korematsu's conviction in 1983 and subsequent reparations.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date of Executive Order 9066 | February 19, 1942 |

| Who signed the order | President Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Who was the order aimed at | Japanese Americans |

| Number of Japanese Americans affected | Over 120,000 |

| Number of those who were American citizens | Two-thirds |

| Ruling | Upheld by the Supreme Court in Korematsu v. United States |

| Rationale | Military necessity |

| Dissent | Justices Frank Murphy, Owen Roberts, and Robert Jackson |

| Later developments | Korematsu's conviction voided in 1983; reparations granted in 1988; Supreme Court overruled its decision in 2018 |

Explore related products

$15.48 $19.99

$7.99 $15.99

What You'll Learn

- The Supreme Court ruled EO 9066 constitutional on the basis of military necessity

- The Court's decision was influenced by the attack on Pearl Harbor

- EO 9066 was intended to apply almost solely to Japanese Americans

- The Court's decision has been widely criticised and described as racist

- The conviction was voided in 1983, and reparations were granted in 1988

The Supreme Court ruled EO 9066 constitutional on the basis of military necessity

In the aftermath of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. This order authorized the War Department to create military areas from which any or all Americans might be excluded, and to provide for the necessary transport, lodging, and feeding of persons displaced from such areas. The order was intentionally vague, allowing officials to exclude "any or all persons" from designated areas, but it was intended to be applied almost solely to persons of Japanese descent.

In Korematsu v. United States, the Supreme Court affirmed the conviction of Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu, a 22-year-old Japanese American who refused to leave his home in San Leandro, California, in violation of one of 108 civilian exclusion orders promulgated under EO 9066. The Court's opinion, written by Justice Hugo Black, declared that "Korematsu was not excluded from the Military Area because of hostility to him or his race," but rather due to military necessity. Black and the Justices who joined his opinion felt that the Executive Order did not show racial prejudice but responded to the strategic imperative of keeping the U.S. secure from sabotage and invasion. They argued that "pressing public necessity" may sometimes justify the existence of restrictions on civil rights, while "racial antagonism never can."

However, Justices Frank Murphy, Owen Roberts, and Robert Jackson dissented, arguing that Korematsu had been convicted of an act not commonly considered a crime: "It consists merely of being present in the state whereof he is a citizen, near the place where he was born, and where all his life he has lived." They contended that the nation's wartime security concerns were not adequate to strip Korematsu and the other internees of their constitutionally protected civil rights.

In 1983, Korematsu's conviction was voided by a California district court. Crucial evidence was discovered that the Solicitor General Charles H. Fahy had withheld a report from the Office of Naval Intelligence, which stated that very few Japanese Americans posed a risk, and that almost all of those who did were already in custody when EO 9066 was enacted. This provided further evidence that the Supreme Court's ruling in Korematsu v. United States was based on a false premise of military necessity.

Federal Jurisdiction: Where the Constitution Guides Court Cases

You may want to see also

The Court's decision was influenced by the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl Harbor by the Empire of Japan on December 7, 1941, launched a rash of fear about national security, especially on the West Coast of the United States. This fear, combined with economic competition, cultural distrust, and long-standing anti-Asian racism, had disastrous consequences for Japanese Americans.

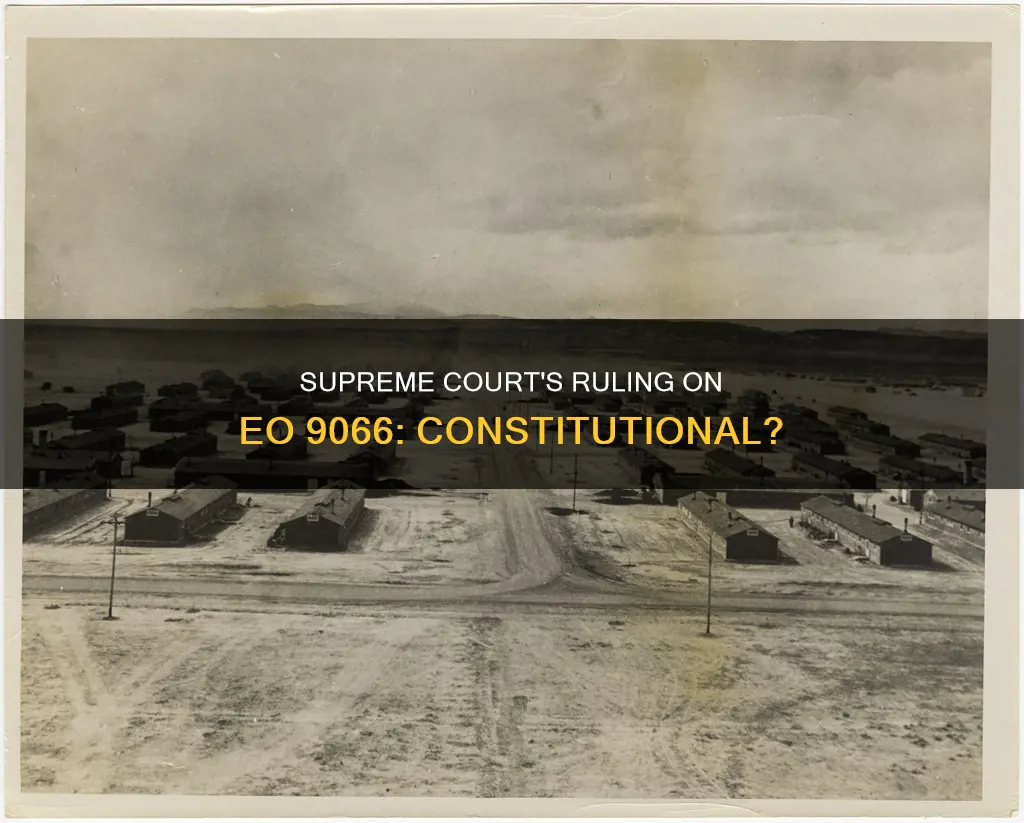

In the aftermath of the attack, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, authorizing the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans from the West Coast to "relocation centers" further inland. The order was based on the claim that Japanese Americans posed a threat to national security and was justified by the need to protect the safety of America's West Coast. The Supreme Court's decision in Korematsu v. United States upheld the constitutionality of this order, despite the fact that it resulted in the incarceration of over 120,000 Japanese Americans, two-thirds of whom were American citizens.

The Court's decision in Korematsu v. United States was influenced by the attack on Pearl Harbor in several key ways. Firstly, the Court accepted the government's argument that the exclusion and detention of Japanese Americans were justified by military necessity. The Court agreed that the presence of Japanese Americans on the West Coast posed a potential threat to national security, given the recent attack on Pearl Harbor and the ongoing war with Japan. The Court's decision was also influenced by the prevailing climate of fear and suspicion towards Japanese Americans, which had intensified following the attack.

Another factor influencing the Court's decision was the broad wording of Executive Order 9066, which authorized the removal of "all persons" deemed a threat to national security, rather than specifically targeting Japanese Americans. This allowed the government to argue that the order was based on legitimate security concerns rather than racial discrimination. However, it is important to note that the Court's decision has been widely criticized and is often cited as one of the worst Supreme Court decisions in history. Critics argue that the Court failed to adequately consider the civil rights of Japanese Americans and that the decision was based on racial prejudice and war hysteria, rather than factual evidence of a security threat.

In conclusion, the attack on Pearl Harbor played a significant role in shaping the Court's decision in Korematsu v. United States. The Court's ruling was influenced by the climate of fear and suspicion following the attack, as well as the broad wording of Executive Order 9066, which allowed for the incarceration of Japanese Americans under the guise of national security. While the Court upheld the constitutionality of the order, the decision has since been recognized as a stain on American jurisprudence, reflecting the pervasive racism and hysteria of the time.

The Constitution's Living Legacy: A Dynamic Document

You may want to see also

EO 9066 was intended to apply almost solely to Japanese Americans

Executive Order 9066, issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, authorized military commanders to prescribe military areas from which any or all Americans may be excluded. While the order did not specify any particular ethnic group, it was quickly applied to the entire Japanese-American population on the West Coast. Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt of the Western Defense Command proceeded to announce curfews that applied only to Japanese Americans. DeWitt first encouraged voluntary evacuation by Japanese Americans from selected areas, and on March 29, 1942, he issued Public Proclamation No. 4, which began the forced evacuation and detention of Japanese Americans from the West Coast.

The Western Defense Command, a U.S. Army military command, ordered "all persons of Japanese ancestry, including aliens and non-aliens" to relocate to internment camps. This resulted in the incarceration of more than 110,000 Japanese Americans in internment camps, two-thirds of whom were American citizens. The Supreme Court, in Korematsu v. United States, upheld the internment of Japanese Americans, stating that it was a "'military necessity' and not based on race. However, the Court has been criticized for ignoring the racial implications of the order and for failing to address the lawfulness of the incarceration.

The impact of EO 9066 fell disproportionately on Japanese Americans, who were the primary targets of the order. While the order itself did not explicitly mention any specific ethnic group, the actions taken by Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt and the Western Defense Command made it clear that the focus was on the Japanese-American community. This is evident from the announcement of curfews and the forced evacuation orders that specifically targeted Japanese Americans.

The reasoning behind EO 9066 was based on the notion of "military necessity" and the need to protect against espionage and sabotage. However, it is important to note that the Ringle Report, a wartime finding by the Office of Naval Intelligence, concluded that very few Japanese individuals posed a risk and that most of those who did were already in custody when EO 9066 was enacted. This report was withheld from the Supreme Court, and the Court's decision in Korematsu v. United States has been widely criticized as "an odious and discredited artifact of popular bigotry."

In conclusion, while EO 9066 was facially neutral and applicable to all Americans, it was intended to apply almost solely to Japanese Americans. The implementation of the order and the actions taken by military commanders clearly demonstrate the discriminatory nature of EO 9066 and its disproportionate impact on the Japanese-American community. The Supreme Court's decision to uphold the internment of Japanese Americans has been criticized for ignoring the racial implications and failing to protect the civil rights of a specific ethnic group.

Founding Fathers: Democracy's Friend or Foe?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The Court's decision has been widely criticised and described as racist

The Supreme Court's decision in Korematsu v. United States, which ruled that the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II was constitutional, has been widely criticised and described as racist. This ruling upheld the conviction of Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu, a 22-year-old Japanese American who refused to leave his home in California, violating a civilian exclusion order issued under Executive Order 9066 (EO 9066).

The Court's decision has faced significant backlash, with scholars describing it as "an odious and discredited artifact of popular bigotry" and "a stain on American jurisprudence". The case is often cited as one of the worst Supreme Court decisions in history. One of the main criticisms is that the Court failed to recognise the racist nature of EO 9066, which resulted in the incarceration of over 100,000 Japanese Americans based on racial prejudice and war hysteria. Despite the facially neutral language of the order, which did not explicitly mention race, its intent and impact were to target and harm a specific racial group.

Justices Frank Murphy and Owen Roberts, in dissent, agreed with this assessment, concluding that the removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast was racially motivated. They were proven right when, in 1948, a federal commission issued a national apology and granted reparations to those who were interned. This was further reinforced by the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which provided additional reparations and acknowledged the racial prejudice that fuelled the decision.

In addition to criticisms of racism, the Court has also been accused of failing to adequately consider the civil rights violations inherent in EO 9066. Justice Robert Jackson, in his dissent, argued that Korematsu was convicted for "being present in the state whereof he is a citizen, near the place where he was born, and where all his life he has lived," highlighting the unjust nature of the conviction. The Court's majority opinion, written by Justice Hugo Black, asserted that Korematsu's exclusion was due to military necessity rather than racial hostility. However, this reasoning has been challenged, with critics arguing that the Court ignored the prolonged incarceration of Japanese Americans and failed to adequately address the serious constitutional issues raised.

In 1983, Korematsu's conviction was voided by a California district court, which found that Solicitor General Charles H. Fahy had withheld evidence from the Supreme Court. Specifically, the Ringle Report from the Office of Naval Intelligence concluded that very few Japanese Americans posed a risk, and most of those who did were already in custody when EO 9066 was enacted. This further undermined the Court's decision and highlighted the racial injustice at its core.

Mayflower Compact's Influence on US Constitution

You may want to see also

The conviction was voided in 1983, and reparations were granted in 1988

Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu, a 22-year-old Japanese-American, refused to leave his home in San Leandro, California, violating one of 108 civilian exclusion orders promulgated under Executive Order 9066. In 1944, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the exclusion, removal, and detention, arguing that it was permissible to curtail the civil rights of a racial group when there was a "pressing public necessity".

Korematsu challenged his conviction in 1983 by filing before the United States District Court for the Northern District of California a writ of coram nobis, which asserted that the original conviction was so flawed as to represent a grave injustice that should be reversed. As evidence, he submitted the conclusions of the CCWRIC report, which stated that the decision had been discredited and that "today the decision in Korematsu lies overruled in the court of history." He also submitted newly discovered internal Justice Department communications demonstrating that evidence contradicting the military necessity for the Executive Order 9066 had been knowingly withheld from the Supreme Court. Specifically, he said Solicitor General Charles H. Fahy had kept from the Court a wartime finding by the Office of Naval Intelligence, the Ringle Report, that concluded very few Japanese represented a risk and that almost all of those who did were already in custody when the Executive Order was enacted. Judge Marilyn Hall Patel denied the government's petition, and concluded that the Supreme Court had indeed been given a selective record, representing a compelling circumstance sufficient to overturn the original conviction. She granted the writ, thereby voiding Korematsu's conviction.

In 1988, Congress passed the Civil Liberties Act, which stated that a “grave injustice” had been done to Japanese American citizens and resident aliens during World War II. It also established a fund that paid some $1.6 billion in reparations to formerly interned Japanese Americans or their heirs. Each surviving internee was granted $20,000 in compensation, equivalent to $44,000 in 2023, with payments beginning in 1990. However, because the law was restricted to American citizens and legal permanent residents, ethnic Japanese who had been taken from their homes in Latin America (mostly from Peru) were not granted reparations.

Understanding the US Constitution: House vs. Senate

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Executive Order 9066 was an order signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, that authorised the removal of people of Japanese ancestry from designated military areas and communities in the United States.

Executive Order 9066 resulted in the mass transportation and relocation of over 120,000 Japanese people, two-thirds of whom were American citizens, to detention camps.

Korematsu v. United States was a 1944 Supreme Court case that upheld the conviction of Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu, a 22-year-old Japanese American who refused to leave his home in California, violating a civilian exclusion order under Executive Order 9066.

The Supreme Court ruled in a 6-3 decision that the detention of Japanese Americans was a "military necessity" and not based on race, upholding the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066.

Yes, the ruling has been widely criticised as one of the worst Supreme Court decisions of all time, with some scholars describing it as "an odious and discredited artifact of popular bigotry". The Court's refusal to address the lawfulness of the incarceration of Japanese Americans and its justification based on "military necessity" have been particularly contentious.