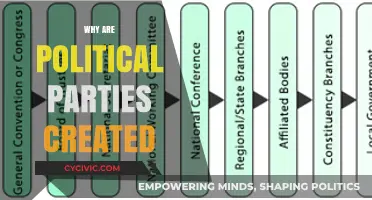

Minor political parties in the United States often struggle to achieve significant success due to a combination of structural, cultural, and financial barriers. The country's two-party system, entrenched by winner-take-all electoral rules and ballot access restrictions, marginalizes smaller parties, making it difficult for them to gain traction or representation. Additionally, the Democratic and Republican parties dominate media coverage and fundraising, leaving minor parties with limited resources and visibility. Cultural factors, such as voter loyalty to established parties and the perception that third-party votes are wasted, further hinder their growth. While minor parties can influence policy debates and push major parties to adopt their ideas, systemic obstacles continue to stifle their ability to achieve lasting electoral success.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) System | Winner-takes-all system discourages voting for minor parties, as votes are seen as "wasted." |

| High Ballot Access Requirements | Strict and costly petition signature requirements in many states to get on the ballot. |

| Lack of Media Coverage | Major parties dominate media attention, leaving minor parties with limited visibility. |

| Funding Disparities | Major parties have access to significantly more campaign funds from donors and PACs. |

| Two-Party Dominance | Historical and cultural entrenchment of the Democratic and Republican parties. |

| Voter Psychology | Strategic voting ("lesser of two evils") reduces support for minor parties. |

| Limited Infrastructure | Major parties have established networks, while minor parties lack grassroots organization. |

| Lack of Electoral College Representation | Minor parties rarely win states due to the winner-takes-all Electoral College system. |

| Polarized Political Climate | Increasing polarization pushes voters toward major parties for ideological alignment. |

| Legal and Institutional Barriers | Debates, public funding, and legislative privileges are often restricted to major parties. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Limited funding and resources hinder campaign reach and visibility

- Winner-take-all electoral system favors major parties disproportionately

- Media coverage focuses predominantly on Democratic and Republican candidates

- Ballot access laws create barriers for minor party participation

- Bipartisan dominance discourages voter trust in smaller alternatives

Limited funding and resources hinder campaign reach and visibility

Minor political parties in the United States often face an uphill battle when it comes to funding, a critical component of any successful campaign. The stark reality is that money fuels political campaigns, enabling candidates to build name recognition, mobilize voters, and compete effectively. Major parties, such as the Democrats and Republicans, have established networks of donors, including wealthy individuals, corporations, and special interest groups, which provide them with substantial financial resources. In contrast, minor parties frequently struggle to attract the same level of funding, leaving them at a significant disadvantage.

Consider the 2020 presidential election, where the Democratic and Republican nominees spent over $1.5 billion combined on their campaigns. Meanwhile, third-party candidates like Jo Jorgensen (Libertarian) and Howie Hawkins (Green Party) raised a mere $4.7 million and $480,000, respectively. This disparity in funding directly translates to limited campaign reach. Major party candidates can afford extensive advertising campaigns, nationwide travel, and sophisticated data analytics to target voters. Minor party candidates, on the other hand, are often forced to rely on grassroots efforts, social media, and volunteer labor, which, while valuable, cannot match the scale and impact of well-funded campaigns.

The lack of resources also hampers minor parties' ability to achieve visibility in the media. News outlets, particularly those with national reach, tend to focus on major party candidates, who are seen as more viable and newsworthy. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle: minor party candidates struggle to gain media attention due to their perceived lack of competitiveness, which in turn makes it harder for them to raise funds and build support. For instance, during the 2016 presidential debates, third-party candidates Gary Johnson (Libertarian) and Jill Stein (Green Party) were excluded because they did not meet the 15% polling threshold set by the Commission on Presidential Debates, a criterion heavily influenced by their limited resources and visibility.

To break this cycle, minor parties must adopt strategic approaches to maximize their limited resources. This includes leveraging digital platforms to reach niche audiences, forming coalitions with like-minded organizations, and focusing on local and state-level races where the cost of campaigning is lower. For example, the Libertarian Party has seen modest success in state legislature races, where targeted spending and grassroots organizing can yield results. Additionally, minor parties can explore alternative funding models, such as crowdfunding and small-dollar donations, to reduce reliance on large donors.

Ultimately, the challenge of limited funding and resources is not insurmountable, but it requires creativity, persistence, and a willingness to rethink traditional campaign strategies. Minor parties must find ways to amplify their message and connect with voters despite financial constraints. While the odds are stacked against them, history has shown that even small breakthroughs can lead to significant long-term gains, gradually shifting the political landscape.

Breaking Barriers: Understanding the Absence of Women in Politics

You may want to see also

Winner-take-all electoral system favors major parties disproportionately

The winner-take-all electoral system, a cornerstone of American elections, awards all of a state's electoral votes to the candidate who wins the popular vote in that state. This mechanism, while straightforward, creates a steep uphill battle for minor political parties. Here’s why: in a system where the margin of victory doesn’t matter—only the outcome—smaller parties struggle to gain traction. For instance, a minor party candidate could secure 45% of the vote in a state and still walk away with zero electoral votes, while the major party candidate pockets all the votes with just 51%. This all-or-nothing structure disincentivizes voters from supporting minor parties, as their votes effectively “waste” in terms of electoral impact.

Consider the 2016 presidential election, where Libertarian candidate Gary Johnson received over 4 million votes nationwide but failed to secure a single electoral vote. Despite his significant popular vote share, the winner-take-all system rendered his support geographically irrelevant. This example illustrates how the system amplifies the dominance of major parties by marginalizing even substantial minor party support. Voters, aware of this dynamic, often succumb to strategic voting, opting for the “lesser of two evils” to avoid splitting the vote and inadvertently aiding their least-preferred candidate.

To understand the systemic bias, imagine a minor party as a startup competing against established corporations. The winner-take-all system is akin to a market where only the top seller gets paid, regardless of how close the competition was. In such a scenario, investors (voters) are less likely to back the startup, fearing their investment will yield no return. This analogy highlights how the system perpetuates a duopoly by making it nearly impossible for minor parties to break through, even when they represent significant portions of the electorate.

Practical steps to mitigate this bias include adopting proportional representation or ranked-choice voting, which allocate power more equitably. For instance, Maine and Nebraska already award electoral votes proportionally by congressional district, a model that could reduce the winner-take-all stranglehold. Until such reforms are implemented, minor parties must focus on local and state-level races where their impact can be more immediate and measurable. Voters, meanwhile, should advocate for systemic changes that reflect the diversity of political thought in America, ensuring that every vote—regardless of party—contributes meaningfully to the democratic process.

Hitler's Rise: The German Political Party He Led to Power

You may want to see also

Media coverage focuses predominantly on Democratic and Republican candidates

Media coverage in the United States disproportionately centers on Democratic and Republican candidates, creating a self-perpetuating cycle that marginalizes minor parties. This phenomenon is not accidental but rooted in the economics of news production. Networks and publications prioritize candidates with the highest likelihood of winning, as these stories generate the most engagement and revenue. Minor party candidates, often polling in single digits, are deemed less newsworthy, leading to a scarcity of coverage that further stifens their ability to gain traction. For instance, during the 2020 election cycle, Libertarian candidate Jo Jorgensen received less than 1% of the media attention given to Biden and Trump, despite being on the ballot in all 50 states.

The analytical lens reveals a deeper structural issue: the media’s role in reinforcing a two-party system. By focusing on Democrats and Republicans, outlets inadvertently signal to voters that these are the only viable options. This "horse-race" narrative, which emphasizes polls, fundraising, and strategic maneuvers, leaves little room for minor parties to articulate their platforms. Even when minor candidates secure debate invitations, as Jill Stein did in 2016, their inclusion is often tokenistic, with limited time to address substantive issues. This imbalance not only undermines democratic diversity but also perpetuates voter apathy toward alternatives.

To break this cycle, a persuasive argument can be made for media outlets to adopt more equitable coverage practices. For example, implementing a "fair time" policy, where candidates receive airtime proportional to their ballot access or grassroots support, could level the playing field. Additionally, fact-checking organizations could play a role by holding major networks accountable for biased coverage. Practical steps include dedicating weekly segments to minor party platforms or hosting multi-party town halls. Such measures would not only amplify underrepresented voices but also enrich public discourse by introducing fresh perspectives on critical issues.

A comparative analysis highlights how other democracies handle this issue. In countries like Germany or New Zealand, proportional representation and public broadcasting standards ensure minor parties receive adequate media attention. The U.S., however, lacks such safeguards, leaving minor parties at the mercy of profit-driven media. For instance, the Green Party in Germany consistently garners 5–10% of media coverage, reflecting its electoral presence, whereas its American counterpart struggles for visibility. This contrast underscores the need for systemic reforms, such as campaign finance adjustments or public funding for diverse political advertising, to address the U.S. media’s two-party bias.

In conclusion, the media’s fixation on Democratic and Republican candidates is both a symptom and a cause of minor parties’ struggles in American politics. By reevaluating coverage practices and adopting more inclusive models, outlets can empower voters to make informed choices beyond the two-party duopoly. This shift would not only benefit minor parties but also strengthen democracy by fostering a more competitive and representative political landscape.

Identity Politics: Exploring Parties Rooted in Language, Ethnicity, or Religion

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Ballot access laws create barriers for minor party participation

Minor political parties in the United States face an uphill battle when it comes to ballot access, a critical step in participating in elections. Ballot access laws, which vary by state, dictate the requirements for a party or candidate to appear on the election ballot. These laws often create significant barriers for minor parties, effectively limiting their ability to compete with the dominant Democratic and Republican parties. For instance, in Texas, a minor party must gather signatures from at least 1% of the total votes cast in the last gubernatorial election, a daunting task that requires substantial resources and organization.

Consider the logistical challenges: in states like California, minor parties must collect tens of thousands of valid signatures within a short timeframe, often with strict validation rules. This process is not only time-consuming but also expensive, as parties may need to hire professionals to ensure compliance with state regulations. For example, the Libertarian Party in California spent over $100,000 in 2020 just to secure ballot access. Such financial burdens disproportionately affect minor parties, which typically operate on shoestring budgets compared to their major counterparts.

The impact of these laws extends beyond financial strain. Ballot access restrictions limit voter choice and stifle political diversity. When minor parties are excluded from the ballot, voters are left with fewer options, often confined to the two major parties. This dynamic perpetuates a cycle where minor parties struggle to gain traction, as their inability to appear on ballots reduces their visibility and ability to build a voter base. For example, in the 2020 election, only 38 states allowed the Green Party on the presidential ballot, significantly hindering their reach.

To address these barriers, minor parties can take strategic steps. First, they should focus on states with less stringent ballot access laws, such as Colorado or Vermont, where the signature requirements are more manageable. Second, leveraging technology and grassroots organizing can streamline signature collection efforts. Tools like online platforms and volunteer networks can reduce costs and increase efficiency. Lastly, minor parties should advocate for ballot access reform, pushing for standardized, less restrictive laws across states.

In conclusion, ballot access laws serve as a formidable obstacle for minor political parties in the U.S., limiting their ability to compete and reducing voter choice. By understanding these barriers and adopting strategic approaches, minor parties can work to overcome these challenges and carve out a space in the American political landscape. Reforming these laws is not just about fairness for minor parties—it’s about fostering a more inclusive and diverse democratic system.

Could DSA Rise to Major Political Party Status in the US?

You may want to see also

Bipartisan dominance discourages voter trust in smaller alternatives

The enduring grip of the Democratic and Republican parties on American politics creates a self-perpetuating cycle of distrust towards minor parties. This bipartisan dominance manifests in structural advantages like ballot access laws, debate participation rules, and campaign financing regulations that favor established parties. These barriers, often justified as safeguards against "fringe" candidates, effectively limit the visibility and viability of smaller alternatives, fostering a perception of futility among voters.

Imagine a marketplace where two mega-corporations control 90% of the shelf space, leaving a handful of smaller brands fighting for scraps. This analogy aptly describes the American political landscape. The duopoly's stranglehold on resources and media attention marginalizes minor parties, making them appear insignificant and incapable of effecting real change.

This structural disadvantage translates into a psychological barrier for voters. The "wasted vote" mentality takes hold, where supporting a minor party candidate feels like throwing away one's vote, as the likelihood of them winning seems remote. This fear is further amplified by the winner-takes-all electoral system, which discourages strategic voting for smaller parties. Voters, conditioned to believe in the inevitability of a two-party outcome, become risk-averse, opting for the "lesser of two evils" rather than exploring alternatives that might better align with their values.

This distrust is not merely theoretical. A 2018 Pew Research Center survey found that only 38% of Americans believe a third party is needed, with many citing concerns about their viability and ability to govern effectively. This skepticism is a direct consequence of the bipartisan system's dominance, which has conditioned voters to view minor parties as perpetual underdogs, lacking the resources and legitimacy to challenge the status quo.

Breaking this cycle requires a multi-pronged approach. Firstly, reforming election laws to level the playing field for minor parties is crucial. This includes easing ballot access requirements, implementing proportional representation systems, and providing public funding for all qualified parties. Secondly, media outlets need to diversify their coverage, giving equal airtime to minor party candidates and their platforms. Finally, voters themselves must overcome the "wasted vote" mentality and recognize the power of their collective voice. Supporting minor parties, even if they don't win immediately, sends a powerful message and can push the major parties to adopt more diverse and inclusive policies.

Educational Attainment: Which Political Party Holds More Degrees?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Minor political parties often face structural barriers, such as winner-take-all electoral systems and ballot access restrictions, which favor the two major parties, Democrats and Republicans.

While minor parties often highlight critical issues, their limited resources, media coverage, and lack of established party infrastructure make it difficult for them to compete effectively.

Although minor parties may resonate with specific voter groups, the American political system’s emphasis on broad coalitions and national appeal often limits their ability to win widespread support.

Yes, minor parties have historically pushed major parties to adopt certain policies (e.g., the Progressive Party and women’s suffrage). However, this influence does not always translate into electoral success for the minor party itself.