The system of two major political parties, often referred to as a two-party system, is a political framework in which power is primarily concentrated between two dominant parties that consistently win elections and hold office. This model is most prominently observed in countries like the United States, where the Democratic Party and the Republican Party have historically dominated the political landscape. In such systems, smaller parties may exist but rarely achieve significant influence, as electoral structures, campaign financing, and media coverage often favor the two major parties. This dynamic can simplify political choices for voters but may also limit ideological diversity and foster polarization, as the parties tend to represent broad coalitions of interests rather than narrower, more specific agendas. Understanding the mechanics and implications of this system is crucial for analyzing governance, policy-making, and democratic representation in two-party-dominated democracies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A political system dominated by two major parties that alternate in power. |

| Examples | United States (Democratic & Republican), United Kingdom (Labour & Conservative). |

| Party Ideology | Typically one party leans left (progressive) and the other right (conservative). |

| Electoral System | Often operates under a winner-take-all or first-past-the-post system. |

| Voter Alignment | Voters tend to align strongly with one of the two major parties. |

| Third Parties | Smaller parties exist but rarely gain significant power or representation. |

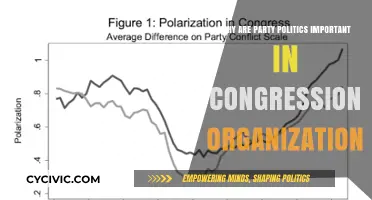

| Policy Polarization | Policies and debates are often polarized between the two parties. |

| Campaign Funding | Major parties dominate fundraising and media attention. |

| Stability | Provides stable governance due to clear majority rule. |

| Criticisms | Accused of limiting voter choice and fostering political gridlock. |

| Global Prevalence | Common in presidential and parliamentary systems with strong party structures. |

Explore related products

$17.49 $26

What You'll Learn

Historical origins of two-party systems in democratic countries

The two-party system, a cornerstone of many democratic nations, often emerges from a complex interplay of historical, social, and political factors. Its origins can be traced back to the early days of democracy, where the need for stable governance and effective representation led to the consolidation of political power into two dominant parties. This phenomenon is not a mere coincidence but a result of specific electoral structures, cultural divisions, and strategic alliances that shape the political landscape.

The Electoral Catalyst: First-Past-the-Post Voting

One of the primary drivers of two-party systems is the first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system, widely used in countries like the United States and the United Kingdom. Under FPTP, the candidate with the most votes in a constituency wins, even if they do not secure a majority. This system inherently disadvantages smaller parties, as votes for them often fail to translate into seats. Over time, voters and politicians alike gravitate toward larger, more viable parties to avoid "wasting" their votes, leading to the dominance of two major political forces. For instance, in the U.S., the Democratic and Republican parties have monopolized power since the mid-19th century, largely due to this electoral mechanism.

Cultural and Ideological Divisions

Beyond electoral mechanics, two-party systems often reflect deep-seated cultural and ideological divides within a society. In the United Kingdom, the historical split between the Conservative Party (representing traditionalism and free markets) and the Labour Party (championing workers' rights and social welfare) mirrors broader societal tensions. Similarly, in Australia, the Liberal-National Coalition and the Australian Labor Party have long embodied the divide between conservative and progressive values. These divisions are not static; they evolve with societal changes, but their persistence reinforces the two-party structure.

Strategic Alliances and Party Consolidation

The formation of two-party systems is also facilitated by strategic alliances and mergers among smaller factions. In Canada, for example, the Conservative Party emerged from the unification of the Progressive Conservative Party and the Canadian Alliance, streamlining the right-wing vote. Such consolidations are often driven by the need to present a united front against a dominant opponent, further entrenching the two-party dynamic. This process is not without conflict, as it requires compromising on ideological purity for the sake of electoral viability.

Historical Accidents and Institutional Design

Sometimes, the rise of two-party systems is the result of historical accidents or specific institutional designs. In India, despite its multi-party democracy, the Congress Party and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have alternately dominated national politics due to regional alliances and the FPTP system in parliamentary elections. Similarly, in Japan, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has maintained near-continuous dominance since 1955, with the opposition fragmented until the rise of the Democratic Party of Japan in the late 20th century. These cases highlight how initial advantages, such as incumbency or organizational strength, can solidify a two-party framework.

Takeaway: A Self-Reinforcing Mechanism

The historical origins of two-party systems reveal a self-reinforcing mechanism. Once established, these systems perpetuate themselves through electoral incentives, cultural entrenchment, and strategic behavior. While they offer stability and simplicity, they also limit ideological diversity and can marginalize minority voices. Understanding their origins is crucial for evaluating their impact on democratic representation and exploring alternatives, such as proportional representation systems, which foster multi-party competition.

Exploring North Carolina's Political Landscape: Which Party Dominates the State?

You may want to see also

Advantages and disadvantages of a two-party political structure

A two-party political structure, where power oscillates between two dominant parties, simplifies the electoral landscape but also limits ideological diversity. This system, exemplified by the United States' Democratic and Republican parties, offers both stability and efficiency in governance. However, it can marginalize smaller parties and stifle nuanced policy debates. Understanding its advantages and disadvantages is crucial for evaluating its impact on democratic processes.

One of the primary advantages of a two-party system is its ability to foster political stability. With only two major parties competing for power, the likelihood of forming a majority government increases, reducing the need for complex coalition-building. This streamlined process allows for quicker decision-making and implementation of policies. For instance, in the U.S., the alternating dominance of Democrats and Republicans has historically ensured a predictable transfer of power, minimizing political chaos. However, this stability comes at the cost of excluding minority viewpoints, as smaller parties often struggle to gain representation.

Another benefit is the clarity it provides to voters. A two-party system simplifies the electoral choices, making it easier for citizens to understand the ideological differences between candidates. This clarity can increase voter engagement, as seen in countries like the U.K., where the Conservative and Labour parties dominate. Yet, this simplicity can also oversimplify complex issues, reducing political discourse to binary choices and discouraging critical thinking among the electorate.

Despite these advantages, a two-party system faces significant drawbacks. One major disadvantage is the suppression of diverse political ideologies. Smaller parties with unique perspectives, such as the Green Party or Libertarians in the U.S., often struggle to gain traction due to structural barriers like winner-takes-all electoral systems. This lack of representation can lead to voter disillusionment and a sense that their voices are not being heard. Additionally, the polarization inherent in a two-party system can exacerbate societal divisions, as parties may adopt extreme positions to differentiate themselves.

To mitigate these disadvantages, some propose reforms such as ranked-choice voting or proportional representation, which could allow smaller parties to gain a foothold. For example, New Zealand's adoption of a mixed-member proportional system has enabled smaller parties to participate in governance, fostering a more inclusive political environment. While these reforms may not eliminate the dominance of two major parties, they can introduce greater ideological diversity and reduce polarization.

In conclusion, a two-party political structure offers the advantages of stability and simplicity but risks excluding minority voices and fostering polarization. Balancing these trade-offs requires thoughtful reforms that preserve the system's efficiency while promoting inclusivity. As democracies evolve, the challenge lies in adapting this structure to better reflect the complexities of modern societies.

Are Political Parties Harmful to Democracy and Civic Engagement?

You may want to see also

Role of elections in maintaining two-party dominance

Elections serve as the lifeblood of two-party systems, reinforcing their dominance through structural and psychological mechanisms. Consider the "winner-takes-all" electoral system used in the United States, where the candidate with the most votes in a district wins all its electoral votes. This system discourages voting for third-party candidates, as voters fear "wasting" their vote on a candidate unlikely to win. For instance, in the 2000 U.S. presidential election, Ralph Nader’s Green Party candidacy drew votes from Al Gore, potentially tipping the outcome in favor of George W. Bush. This dynamic, known as "Duverger’s Law," illustrates how electoral structures inherently favor two major parties by marginalizing smaller ones.

The role of elections in maintaining two-party dominance extends beyond voting mechanics to campaign financing and media coverage. Major parties in two-party systems often secure disproportionate funding and media attention, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of visibility and power. In the U.K., for example, the Conservative and Labour parties dominate election coverage, while smaller parties like the Liberal Democrats struggle to gain traction. This imbalance is exacerbated by electoral rules, such as the U.K.’s first-past-the-post system, which rewards parties with concentrated regional support. As a result, elections act as a filter, amplifying the voices of the two major parties while silencing others.

To break this cycle, voters must strategically navigate the electoral landscape. One practical tip is to focus on local and state elections, where third-party candidates often have a better chance of winning due to lower barriers to entry. For instance, the Libertarian Party in the U.S. has successfully elected state legislators by targeting less competitive races. Additionally, advocating for electoral reforms, such as ranked-choice voting or proportional representation, can level the playing field for smaller parties. These reforms, already implemented in countries like Australia and New Zealand, reduce the "spoiler effect" and encourage more diverse political representation.

Despite these strategies, the psychological impact of two-party dominance remains a significant hurdle. Voters often internalize the belief that only major parties can effect change, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. This mindset is reinforced during elections, as media narratives and polling data consistently highlight the two dominant parties. To counter this, voters should educate themselves on third-party platforms and consider their alignment with personal values, rather than defaulting to the "lesser of two evils." By doing so, they can challenge the status quo and contribute to a more pluralistic political system.

In conclusion, elections are not merely a tool for selecting leaders but a structural force that sustains two-party dominance. From voting systems to media dynamics, every aspect of the electoral process is designed to favor major parties. However, by understanding these mechanisms and adopting strategic voting behaviors, individuals can begin to dismantle this dominance. Whether through supporting local candidates, advocating for reform, or reevaluating voting habits, the power to reshape the political landscape lies within the electorate’s hands.

Abraham Lincoln's Political Party: Unraveling His Affiliation and Legacy

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact of third parties on the two-party system

Third parties, despite rarely winning elections, significantly influence the two-party system by shaping policy agendas and forcing major parties to address neglected issues. For instance, the Green Party’s consistent advocacy for environmental policies has pushed both Democrats and Republicans to incorporate climate change into their platforms. Similarly, the Libertarian Party’s emphasis on limited government has spurred debates on fiscal responsibility and individual freedoms. These parties act as policy accelerators, compelling the major parties to adapt or risk alienating segments of the electorate.

Consider the strategic role of third parties in elections. While they seldom secure victory, their presence can alter outcomes by splitting votes. Ross Perot’s 1992 presidential campaign, for example, drew nearly 19% of the popular vote, potentially costing George H.W. Bush reelection. This spoiler effect forces major parties to recalibrate their strategies, often by co-opting third-party ideas or targeting their voter bases. However, this dynamic also highlights the structural barriers third parties face, such as winner-take-all electoral systems and ballot access restrictions, which limit their direct power.

To maximize their impact, third parties often employ a long-term strategy of ideological infiltration rather than immediate electoral success. By consistently championing specific issues, they create pressure points that major parties cannot ignore. For instance, the Progressive Party’s early 20th-century push for labor rights and antitrust laws laid the groundwork for New Deal policies decades later. This incremental approach demonstrates how third parties can act as catalysts for systemic change, even without holding office.

Practical engagement with third parties requires understanding their limitations and strengths. Voters interested in supporting these parties should focus on local and state-level races, where the two-party dominance is less entrenched. Additionally, advocating for electoral reforms like ranked-choice voting can level the playing field, allowing third parties to compete more fairly. While the two-party system remains dominant, third parties serve as essential checks, ensuring that the political discourse remains dynamic and responsive to diverse perspectives.

The Anti-Federalists' Push for the Bill of Rights Explained

You may want to see also

Comparison of two-party systems across different nations

Two-party systems, where political power oscillates between two dominant parties, manifest differently across nations, shaped by historical, cultural, and institutional contexts. In the United States, the Democratic and Republican parties dominate due to a first-past-the-post electoral system, which marginalizes smaller parties. This system fosters polarization, as parties cater to their bases rather than the center. In contrast, the United Kingdom’s Conservative and Labour parties operate within a parliamentary system, where coalition governments are less common but still possible. The UK’s system allows for more ideological flexibility, as seen in Labour’s shift from socialism to centrism under Tony Blair. These differences highlight how electoral rules and political traditions influence party dynamics.

Consider Australia, where the Liberal-National Coalition and the Australian Labor Party dominate. Unlike the U.S., Australia uses a preferential voting system, which reduces the winner-takes-all effect and encourages parties to appeal to a broader electorate. This system has led to more moderate policies and less extreme polarization. Meanwhile, in India, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Indian National Congress (INC) dominate, but the country’s federal structure and diverse population make regional parties significant players. India’s two-party dominance is thus more fluid, with regional alliances often determining national outcomes. These examples illustrate how electoral systems and regional factors shape the functioning of two-party systems.

A persuasive argument can be made that two-party systems, while stable, often stifle diverse voices. In the U.S., third parties like the Greens or Libertarians struggle to gain traction, limiting policy debates to the agendas of the two major parties. This contrasts with Germany’s multi-party system, where smaller parties like the Greens and FDP play pivotal roles in coalition governments. However, two-party systems can also provide clarity and decisiveness, as seen in the UK’s ability to form majority governments. The trade-off between stability and inclusivity is a recurring theme in the comparison of these systems.

To analyze further, examine how two-party systems handle crises. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. response was fragmented along partisan lines, with Democrats and Republicans disagreeing on lockdowns and vaccine mandates. In contrast, Australia’s bipartisan approach led to more cohesive policies, such as strict border closures and income support programs. This comparison underscores the impact of party cooperation—or lack thereof—on governance effectiveness. Nations with two-party systems must balance competition with collaboration to address national challenges.

In conclusion, two-party systems are not monolithic; their characteristics depend on the nation’s electoral rules, cultural norms, and historical trajectory. While they offer stability and clarity, they can also limit political diversity and exacerbate polarization. Policymakers and citizens alike should study these variations to understand how their system compares and where reforms might be needed. For instance, adopting elements of Australia’s preferential voting could reduce U.S. polarization, while India’s federalism offers lessons in managing regional diversity within a two-party framework. Each system has strengths and weaknesses, and their comparison provides valuable insights for improving democratic governance.

Understanding the Role of State Party Conventions in Shaping Political Agendas

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The system of two major political parties, often referred to as a two-party system, is a political structure where two dominant parties consistently win the majority of elected offices and hold significant power in government.

In a two-party system, power is concentrated between two major parties, whereas a multi-party system involves multiple parties competing for influence, often leading to coalition governments and more diverse representation.

The United States is a prominent example of a two-party system, with the Democratic Party and the Republican Party dominating national politics. Other examples include the United Kingdom (Conservatives and Labour) and Australia (Liberal/National Coalition and Labor).

Advantages include political stability, clearer choices for voters, and more efficient governance due to reduced fragmentation. It also encourages parties to appeal to a broader electorate.

Critics argue that it limits voter choice, marginalizes smaller parties and independent candidates, and can lead to polarization as the two major parties focus on differentiating themselves rather than addressing nuanced issues.