The Constitution of Japan, which includes the right to education, was written in 1946 and adopted in 1947 while the country was under Allied occupation following World War II. The constitution was primarily written by American civilian officials, including U.S. General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers. MacArthur directed Prime Minister Kijūrō Shidehara to draft a new constitution, and while a committee of Japanese scholars reviewed and modified the document, the process was supervised by MacArthur. The constitution was based on principles of popular sovereignty, pacifism, and individual rights, and it reduced the role of the emperor to a ceremonial position.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date of enactment | 15 November 1946 |

| Authors | Milo Rowell, Courtney Whitney, Beate Sirota, and others |

| Articles | 102 |

| Right to vote | Cannot be denied on the grounds of "race, creed, sex, social status, family origin, education, property, or income" |

| Equality between sexes | Explicitly guaranteed in relation to marriage and childhood education |

| Peerage | Forbidden |

| Elections | Universal adult suffrage, the secret ballot, and the right to choose public officials and dismiss them |

| Slavery | Involuntary servitude is only permitted as punishment for a crime |

| Religion | Separation of religion and state; the state cannot grant privileges or authority to a religion or conduct religious education |

| Education | All people have the right to receive an equal education, regardless of ability |

| Financial assistance | National and local governments must provide financial assistance to those who need it for economic reasons |

| Disability support | National and local governments must provide educational support to people with disabilities |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The Meiji Constitution of 1889

The Meiji Constitution established a form of mixed constitutional and absolute monarchy, based on German and British models. It provided for an emperor with considerable political power, including supreme control of the army and navy, and the power to declare war, make peace, and conclude treaties. The emperor governed with the advice of his ministers, but in practice, the actual head of government was the prime minister, who was appointed by the emperor along with the cabinet. The Meiji Constitution also established an independent judiciary and limited the power of the executive branch.

The Meiji Constitution did not include a provision on the right to education. Instead, the Meiji government determined that the fundamental principle on education should be provided by the Imperial Rescript on Education (Kyōiku Chokugo) of 1890, which emphasised traditional Confucian and Shinto values. The new minister of education, Mori Arinori, played a central role in enforcing a nationalistic educational policy and revising the school system.

The Meiji Constitution remained in force until May 2, 1947, when it was replaced by a new "Postwar Constitution" during the Allied occupation of Japan. The Postwar Constitution replaced imperial rule with a Western-style liberal democracy, stating that "sovereign power resides with the people".

Stapling Documents: A Single Contract or Separate Agreements?

You may want to see also

Mori Arinori, the new Minister of Education

Mori Arinori was the new Minister of Education in Japan in 1885, when the cabinet system was installed. He was a central figure in enforcing a nationalistic educational policy and worked out a vast revision of the school system. This set the foundation for the nationalistic educational system that developed during the following period in Japan.

Mori Arinori's educational policies were based on nationalism and imperialism. He believed that the nation-state had the primary role in mobilizing individuals and children into service of the state. Western-style schools were introduced as a means to reach this goal. By the 1890s, schools were generating new sensibilities regarding childhood, and Japan had its own group of reformers, child experts, magazine editors, and well-educated mothers who bought into the new sensibility.

Mori's policies built upon the Meiji Restoration of 1868, which aimed to establish a politically unified and modernized state. The Meiji government introduced science and technology from Europe and America, and the country rapidly adopted useful aspects of Western industry and culture. The Meiji Restoration also brought about drastic reforms of the social system, including the spread of literacy and education. By the end of the Tokugawa period, there were more than 11,000 schools attended by 750,000 students.

Mori Arinori's educational reforms were also influenced by Confucian morality and values. Elementary schools taught shūshin, or national moral education, with a textbook that had overtones of Confucian morality. This continued a long tradition of Confucian education in Japan, which dated back to the sixth century when Chinese learning was introduced at the Yamato court. Confucian classics were memorized, and reading and reciting them were common methods of study.

Mori Arinori's work as Minister of Education was instrumental in shaping Japan's educational system. His policies set the tone for a nationalistic and imperialistic approach to education, which remained influential until the end of World War II.

Folding the US Constitution: Pocket-Sized Guide

You may want to see also

Confucian morality and ethics

The Meiji Constitution, the constitution of the Empire of Japan, was promulgated in 1889. It established a balance between imperial power and parliamentary forms. Mori Arinori, the new Minister of Education, was a central figure in enforcing a nationalistic educational policy. He revised the school system, setting a foundation for the nationalistic educational system that developed in Japan thereafter. Elementary schools taught shūshin (national moral education) as the core of their curricula, with textbooks containing overtones of Confucian morality.

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behaviour that originated in ancient China. It is described as a tradition, philosophy, religion, theory of government, or way of life. Founded by Confucius in the Hundred Schools of Thought era (c. 500 BCE), Confucianism integrates philosophy, ethics, and social governance, with a core focus on virtue, social harmony, and familial responsibility. It emphasises virtue through self-cultivation and communal effort. Key virtues include ren ("benevolence"), yi ("righteousness"), li ("propriety"), zhi ("wisdom"), and xin ("sincerity"). These values, deeply tied to the notion of tian ("Heaven"), present a worldview where human relationships and social order are manifestations of sacred moral principles. While Confucianism does not emphasise an omnipotent deity, it upholds tian as a transcendent moral order.

Confucian ethics is characterised by the promotion of virtues, encompassed by the Five Constants, elaborated by Confucian scholars during the Han dynasty. The Five Constants are: Ren, Yi, Li, Zhi, and Xin. These are accompanied by the classical four virtues, one of which, Yi, is also included among the Five Constants. Other traditionally Confucian values include "honesty", "bravery", "incorruptibility", "kindness", and "forgiveness". Confucian ethical codes are described as humanistic and may be practised by all members of society.

Confucianism holds that in order to govern others, one must first cultivate inner virtue to be a moral elite. Confucius' ideal of good government is one led by a superior man (junzi), that takes effective use of "culture and tradition" and relies less on law and punishment. The sage or wise is the ideal personality in Confucianism, but it is very hard to become one. Confucius created the model of junzi, which may be achieved by any individual through the discipline of one's mind and actions. The junzi disciplines himself and enforces his rule by acting virtuously, leading others to follow his example. The ultimate goal is for the government to behave like a family, with the junzi as a beacon of filial piety.

Confucianism has been credited with the rise of the East Asian economy in the late twentieth century, and it remains influential in China, Korea, Japan, Vietnam, and regions with significant Chinese diaspora. Confucian work ethics and moral persuasions continue to be effective in disciplining workers and consumers in East Asia.

Understanding the Legal Definition of a Child in Uganda

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

The Tokugawa regime

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the Tokugawa period, lasted from 1603 to 1867 and was a time of peace, stability, and growth in Japan. Tokugawa Ieyasu, the first Tokugawa shogun, established hegemony over the entire country by strategically balancing the power of hostile domains with allies and collateral houses. He had direct control over a quarter of Japan, while the remaining land was divided among the daimyos, similar to feudal barons, who pledged their allegiance to the shogun in exchange for the right to rule their domains.

During the Tokugawa period, Japan experienced rapid economic growth and urbanization, which led to the rise of the merchant class and Ukiyo culture. Improved farming methods, the cultivation of cash crops, standardized coins, weights, and measures, as well as improved road networks, all contributed to the expansion of commerce and the manufacturing industry. Large urban centers developed in Edo, Osaka, and Kyoto, and Japan became one of the world's most sophisticated premodern commercial societies.

However, in the late 18th and 19th centuries, the daimyo and samurai classes began to face financial difficulties as their income, tied to agricultural production, could not keep pace with other sectors of the economy. The Tokugawa shogunate faced peasant uprisings, samurai unrest, and financial problems during its final years. The growing threat of Western encroachment and demands for the restoration of direct imperial rule ultimately led to the overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1867, marking the end of the Tokugawa regime and the beginning of the Meiji Restoration.

The Meiji Restoration, which began in 1868, ushered in drastic social reforms and the establishment of a politically unified and modernized state. The Meiji government introduced science and technology from Europe and America, and the new minister of education, Mori Arinori, played a central role in enforcing a nationalistic educational policy. The Meiji Constitution of 1889 established a balance between imperial power and parliamentary forms, and the Imperial Rescript on Education of 1890 provided a structure for national morality, emphasizing Confucian and Shinto values.

Weekly Car Rental: What Constitutes a Rental Company?

You may want to see also

The Meiji Restoration

During the Edo period, Japan had been under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate, a military government led by the shōgun, or "great general". However, by the mid-19th century, the shogunate was facing economic and political difficulties, including challenges to its policy of sakoku, or national isolation, by foreign powers such as the United States.

Discontent was also growing among the samurai class, who were concerned about the shogunate's ability to protect the country from foreign influence. In 1867, Emperor Kōmei died, and the young Mutsuhito ascended the throne as Emperor Meiji. Offers for a mediated settlement were proposed by the new shōgun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, but these were ignored, and the anti-Tokugawa alliance, led by Satsuma and Chōshū, moved to overthrow the shogunal system. On January 3, 1868, the alliance staged a coup d'état in the ancient imperial capital of Kyōto, announcing the end of shogunal rule and proclaiming Emperor Meiji as the new ruler of Japan.

The Meiji period (1868-1912) was an era of rapid modernisation and Westernisation in Japan. The country adopted Western ideas, production methods, and technology, and developed a strong army and navy. The Meiji government also introduced universal education and built railroads and telegraph lines. By the end of the Meiji period, Japan had become a major international power and had regained complete control of its foreign trade and legal system.

Legislative Branch: Framers' Vision and Intent

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

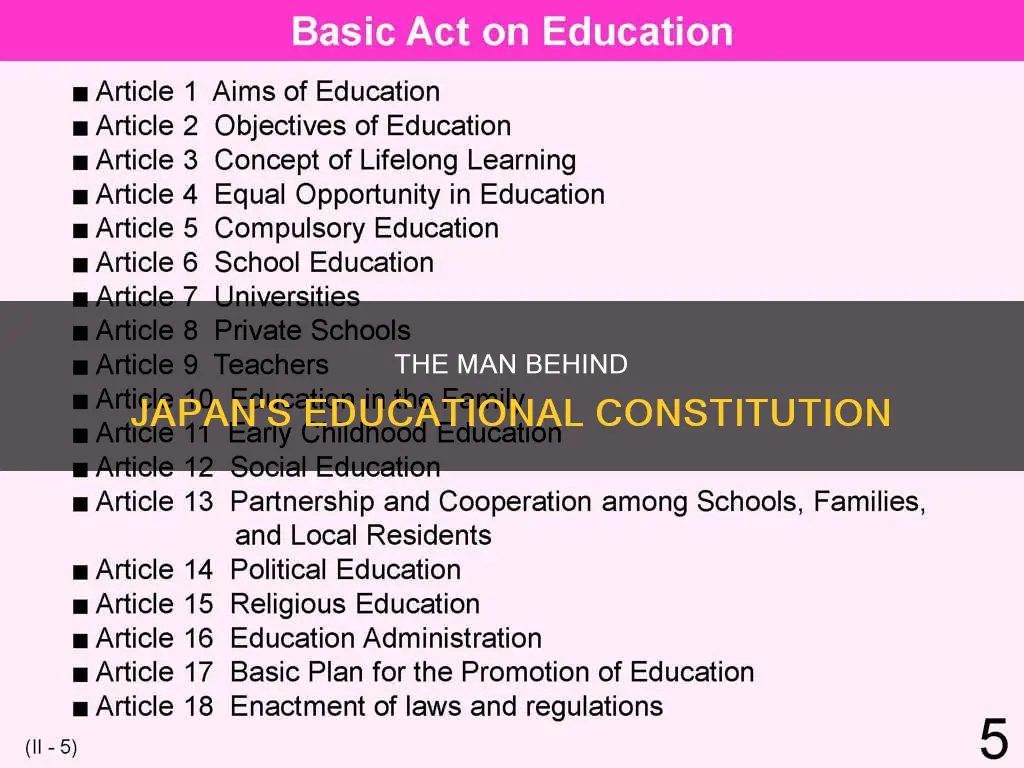

The Fundamental Law of Education, also known as "The Education Constitution", is a Japanese law that sets the standards for the Japanese education system. It was created by the Imperial Japanese Diet, the last Imperial Diet conducted under the Imperial Japanese Constitution.

The Fundamental Law of Education is the basis for interpreting and applying various laws and ordinances regarding education in Japan. It contains a preamble and 18 articles, outlining the purposes and objectives of education, and providing for equal opportunity in education, compulsory education, coeducation, social education, political education, religious education, educational administration, etc.

The current Fundamental Law of Education was enacted on December 22, 2006, replacing the previous 11-article Act of March 31, 1947.

The previous Fundamental Law of Education, also known as the "old fundamental law of Education", was enacted in 1947 under the auspices of SCAP (Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers). It was written in the spirit of the new Japanese Constitution, representing a radical means of education reform and replacing the pre-World War II Imperial Rescript on Education, which was based on Confucianist thought.

The Meiji Constitution, also known as the Constitution of the Empire of Japan, was promulgated in 1889 and established a balance between imperial power and parliamentary forms. It did not include a provision on the right to education, but it set the foundation for a nationalistic educational system in Japan.

![Japan mites picture book (1980) ISBN: 4881370103 [Japanese Import]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51vpg+9bdAL._AC_UY218_.jpg)