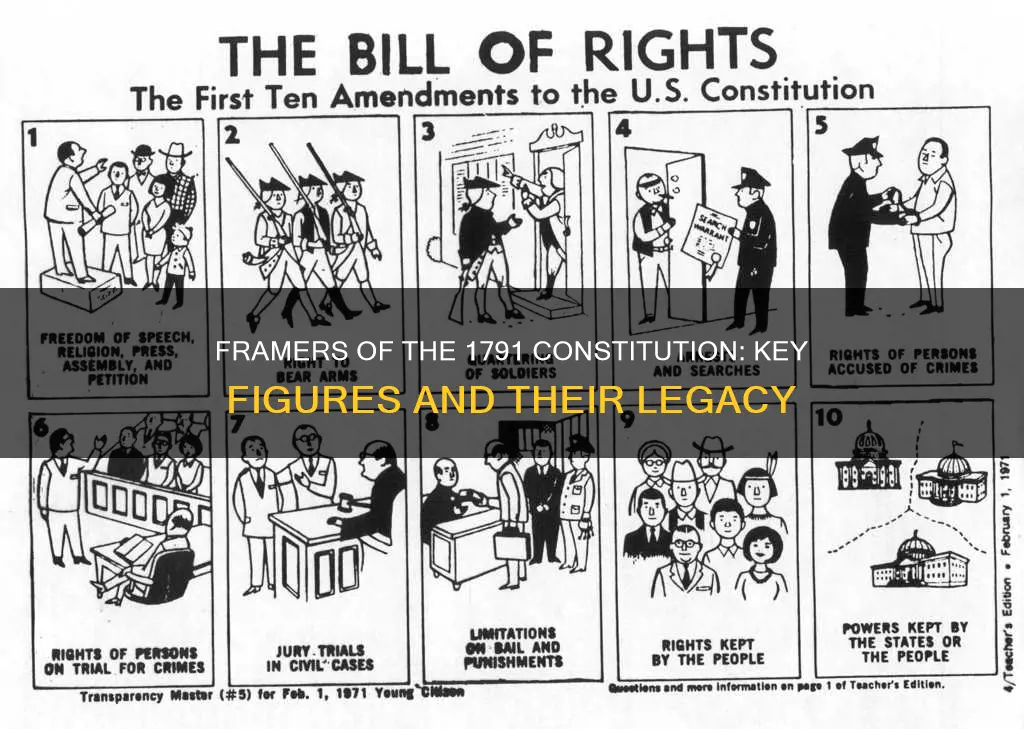

The Constitution of 1791 was the first written constitution of France, turning the country into a constitutional monarchy following the collapse of the absolute monarchy of the Ancien Régime. It was passed in September 1791 and was drafted by the National Constituent Assembly, a group of moderates who hoped to create a better form of royal government. The constitution was reluctantly accepted by King Louis XVI, who had tried to flee France the month before, and it redefined the organisation of the French government, citizenship, and the limits to the powers of the government.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Country | France |

| Type of Document | First written constitution |

| Date of Adoption | Autumn of 1791 |

| Date Passed | September 1791 |

| Assembly | National Assembly |

| Assembly Type | Legislative body |

| Executive Branch | King and royal ministers |

| Judiciary | Independent of the legislative and executive branches |

| Citizen Classification | Active citizens and passive citizens |

| Active Citizen Criteria | Male property owners over the age of 25 |

| Passive Citizen Criteria | Poorer individuals with no voting rights |

| Rights Granted to Women | None |

| Monarch | Louis XVI |

| Monarchy Type | Constitutional |

Explore related products

$65.54 $132

$51

What You'll Learn

The National Assembly

The Constitution of 1791 was the first written constitution in France. It was drafted by the National Assembly, a group of moderates who aimed to create a better form of royal government rather than something radically new. The Assembly was formed by the Third Estate, which consisted of the common people, on 13 June 1789, and they assembled in a Versailles tennis court on 20 June 1789, pledging not to disband until France had a working constitution.

The Assembly faced controversies regarding the level of power to be granted to the king and the form the legislature would take. They decided to grant the king a suspensive veto, which could be overridden by three consecutive legislatures, to balance the interests of the people. The king's title was also amended from 'King of France' to 'King of the French', implying that his power emanated from the people and the law, not from divine right or national sovereignty.

Camping Stoves: Open Burn Laws in Virginia

You may want to see also

The Third Estate

On June 17, 1789, the Third Estate declared themselves to be the National Assembly, inviting the other estates to join them but making clear that they would conduct the nation's affairs with or without them. This was a direct challenge to the authority of the king, who attempted to resist this assertion of power by the common people. The king ordered the hall where the National Assembly met to be closed, but the Assembly simply moved to a nearby tennis court, where they swore the Tennis Court Oath, agreeing not to separate until they had settled the constitution of France. This was a pivotal event in the early days of the French Revolution, with the people asserting that political authority derived from them, rather than solely from the king.

The deputies of the Third Estate believed that any reforms to the French state must be outlined in and guaranteed by a written constitution. This would become the fundamental law of the nation, defining and limiting the power of the government and protecting the rights of citizens. The Third Estate was dominated by men of legal professions, and the Assembly included critical figures such as Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès, author of the pamphlet 'What Is the Third Estate?'.

Interpreting the Constitution: The Legislative Branch's Role

You may want to see also

Active and passive citizens

The Constitution of 1791 was France's first attempt at a national constitution, drafted by the National Assembly and passed in September 1791. It was inspired by Enlightenment theories and foreign political systems, and aimed to create a better form of royal government. The Constitution redefined the organisation of the French government, citizenship, and the limits of the government's powers. It also abolished many institutions that were considered harmful to liberty and equality of rights.

The Assembly, as the framers of the Constitution, decided to separate the population into two classes: 'active citizens' and 'passive citizens'. Active citizens were those entitled to vote and stand for office. They were males over the age of 25 who paid annual taxes equivalent to at least three days' wages. In other words, they were the propertied class. Passive citizens, on the other hand, did not have the right to vote and only possessed civil rights. They were the poorer class.

The distinction between active and passive citizens created tensions during the revolution. Passive citizens, particularly women, started to call for more rights. Olympe de Gouges, for example, published her 'Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen' in 1791, drawing attention to the need for gender equality. Despite these calls for equality, the French Revolution did not lead to a recognition of women's rights. Women lacked liberties such as education, freedom of speech, and freedom of worship.

The Constitution of 1791 was not egalitarian by today's standards. It was also outdated by the time it was adopted, as it had been overtaken by the events of the revolution and growing political radicalism. Nevertheless, it was an important step in France's transition to constitutional monarchy and the establishment of popular sovereignty.

The Louisiana Purchase: Was it Constitutional?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The king's revised role

The Constitution of 1791 was the first written constitution of France, and it turned the country into a constitutional monarchy following the collapse of the absolute monarchy of the Ancien Régime. The constitution redefined the organisation of the French government, citizenship, and the limits of the government's powers.

The role of the king was a central controversy in the drafting of the Constitution of 1791. The National Assembly, as the constitution-framers, were afraid that if only representatives governed France, it would be ruled by their self-interest. Thus, the king was allowed a suspensive veto to balance out the interests of the people. However, this also weakened the king's executive authority. The king's title was amended from 'King of France' to 'King of the French', implying that his power emanated from the people and the law, not from divine right or national sovereignty.

The king retained the right to form a cabinet and select and appoint ministers. However, the constitution also established the independence of the judiciary from the executive and legislative branches. The king's spending was reduced by around 20 million livres, and he was granted a civil list (public funding) of 25 million livres.

The constitution was reluctantly accepted by King Louis XVI in September 1791, and he took an oath to uphold and respect it. However, the king showed no faith in the constitution, and by October 1789, he was already working to make it unworkable. Despite this, the National Constituent Assembly decided that Louis XVI would remain king under a constitutional monarchy.

Amendments to the Constitution: A Historical Overview

You may want to see also

The Constitutional Committee

The Constitution of 1791 was the first written constitution of France. It was drafted by a committee of the National Assembly, a group of moderates who aimed to create an improved form of royal government rather than a radically new one. The National Assembly was formed by the Third Estate on June 13, 1789, and one of its primary goals was to write a constitution.

A twelve-member Constitutional Committee was convened on July 14, 1789, to draft most of the constitution's articles. The main controversies at the time centred on the level of power to be granted to the king of France and the form the legislature would take. The Constitutional Committee proposed a bicameral legislature, but this was rejected in favour of a single house. The next day, they proposed an absolute veto, but this was also rejected in favour of a suspensive veto, which could be overridden by three consecutive legislatures.

A second Constitutional Committee was soon formed, including Talleyrand, Abbé Sieyès, and Le Chapelier from the original group, as well as new members Gui-Jean-Baptiste Target, Jacques Guillaume Thouret, Jean-Nicolas Démeunier, François Denis Tronchet, and Jean-Paul Rabaut Saint-Étienne, all of the Third Estate.

The Constitution of 1791 turned France into a constitutional monarchy following the collapse of the absolute monarchy of the Ancien Régime. It redefined the organisation of the French government, citizenship, and the limits of government power. The National Assembly aimed to represent the interests of the general will, abolishing institutions deemed "injurious to liberty and equality of rights". The Assembly's belief in a sovereign nation and equal representation was reflected in the constitutional separation of powers. The National Assembly formed the legislative body, the king and royal ministers made up the executive branch, and the judiciary was independent of the other two branches.

The Electoral Process: Constitutional Framework

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Constitution of 1791 was drafted by a committee of the National Assembly, also known as the National Constituent Assembly.

The committee was made up of 12 members, including Talleyrand, Abbé Sieyès, Le Chapelier, Gui-Jean-Baptiste Target, Jacques Guillaume Thouret, Jean-Nicolas Démeunier, François Denis Tronchet, and Jean-Paul Rabaut Saint-Étienne, all of the Third Estate.

The Constitution distinguished between "active citizens" and "passive citizens". Active citizens were entitled to vote and stand for office, and were males over the age of 25 who paid annual taxes equivalent to at least three days' wages. Passive citizens did not have the right to vote or hold office.

The Constitution of 1791 turned France into a constitutional monarchy, with sovereignty residing in the Legislative Assembly. The king retained certain powers, including the right to form a cabinet and appoint ministers, but his title was changed to "King of the French", implying that his power came from the people and the law, rather than divine right.

![L'Ami des patriotes, ou Le défenseur de la Révolution. [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61p2VzyfGpL._AC_UY218_.jpg)

![Analyse et parallèle des trois constitutions polonaises 1833 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61IX47b4r9L._AC_UY218_.jpg)