The idea that political parties are detrimental to effective governance can be traced back to the Founding Fathers of the United States, particularly George Washington and James Madison. In his Farewell Address, Washington warned against the baneful effects of the spirit of party, arguing that factions and political parties would undermine national unity, foster division, and prioritize partisan interests over the common good. Madison, in *Federalist No. 10*, acknowledged the inevitability of factions but expressed concern that organized political parties could lead to tyranny of the majority and corrupt the democratic process. Their skepticism was rooted in the belief that parties would distract from principled governance, encourage polarization, and erode the stability of the young republic. This perspective has since been echoed by various thinkers and reformers who view political parties as obstacles to impartial decision-making and genuine representation in government.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | George Washington |

| Role | First President of the United States |

| Time Period | 1789-1797 |

| Key Quote | "However [political parties] may now and then answer popular ends, they are likely in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion." (Farewell Address, 1796) |

| Concerns about Political Parties | 1. Factionalism: Believed parties would divide the nation and prioritize party interests over the common good. 2. Corruption: Feared parties would become tools for power-hungry individuals to manipulate the system. 3. Threat to Unity: Saw parties as a threat to national unity and stability. |

| Modern Relevance | Washington's warnings are often cited in discussions about partisan polarization and gridlock in modern American politics. |

Explore related products

$9.53 $16.99

What You'll Learn

- Founding Fathers' Concerns: Early U.S. leaders like Washington and Madison warned against party divisions

- Faction Risks: Parties were seen as factions, threatening unity and fostering conflict

- Corruption Fears: Parties were believed to prioritize power over public good, leading to corruption

- Polarization Effects: Early critics argued parties would deepen ideological divides and gridlock governance

- Democracy Distortion: Parties were thought to manipulate voters, undermining true democratic representation

Founding Fathers' Concerns: Early U.S. leaders like Washington and Madison warned against party divisions

The Founding Fathers of the United States, particularly George Washington and James Madison, harbored deep reservations about the emergence of political parties. In his Farewell Address of 1796, Washington cautioned that parties could become "potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people." He feared factions would prioritize self-interest over the common good, fostering division and undermining the young nation’s unity. Madison, often called the Father of the Constitution, echoed these concerns in *Federalist No. 10*, where he warned of factions leading to tyranny and instability. Despite this, both men witnessed the rise of parties during their lifetimes, a development they viewed as a betrayal of the nation’s founding principles.

Analyzing their warnings reveals a prescient understanding of the dangers of partisan polarization. Washington’s concern about parties as tools for manipulation highlights how factions could distort public opinion and concentrate power in the hands of a few. Madison’s focus on factions as threats to liberty underscores the risk of majority tyranny, where dominant parties might oppress minority voices. These fears were not merely theoretical; the early 1790s saw the emergence of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties, whose bitter rivalry often paralyzed governance. For instance, the Jay Treaty of 1795 became a partisan flashpoint, with Federalists supporting it and Democratic-Republicans opposing it, illustrating how party loyalty could overshadow national interests.

To mitigate these risks, the Founding Fathers proposed structural safeguards rather than outright bans on parties. Madison’s solution in *Federalist No. 10* was to create a large, diverse republic where competing interests would balance one another, making it harder for any single faction to dominate. Washington, in his Farewell Address, emphasized the importance of civic virtue and education, urging citizens to rise above party loyalties. These strategies, however, proved insufficient against the tide of party politics. By the early 19th century, parties had become entrenched, shaping American governance in ways the Founders had hoped to avoid.

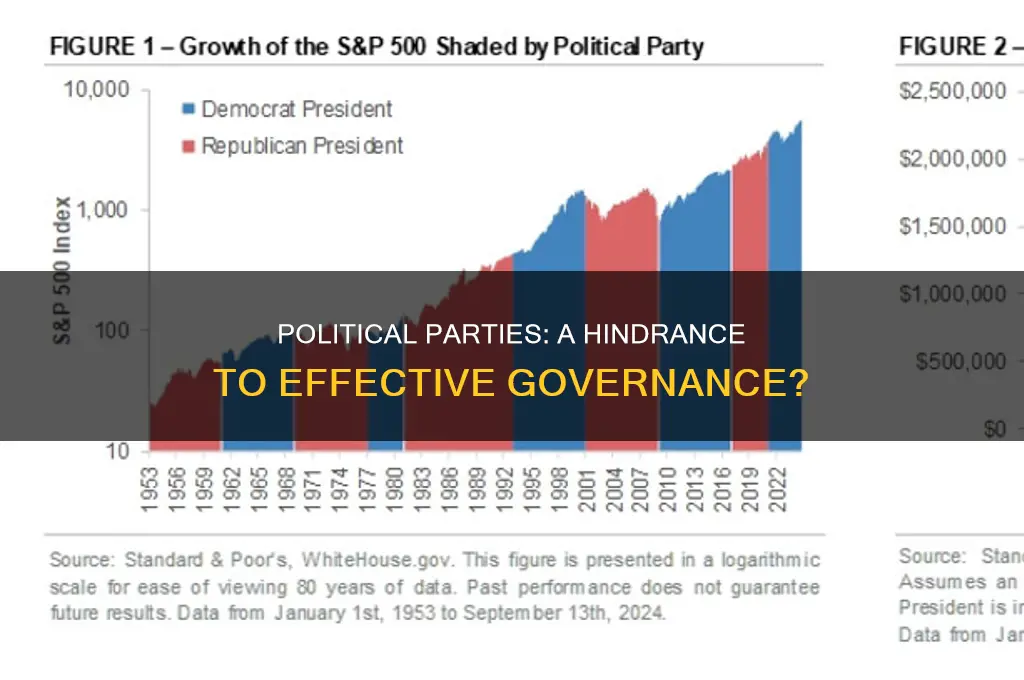

Comparing their warnings to modern political landscapes reveals striking parallels. Today’s hyper-partisan environment, marked by gridlock and polarization, reflects the very dangers Washington and Madison foresaw. The Founders’ concerns serve as a cautionary tale, reminding us that unchecked partisanship can erode democratic institutions. Practical steps to address this include fostering cross-party collaboration, reforming campaign finance laws to reduce the influence of special interests, and encouraging civic education that emphasizes shared national values over party loyalty.

In conclusion, the Founding Fathers’ warnings about political parties were rooted in a profound understanding of human nature and the fragility of democracy. Their insights remain relevant, offering a roadmap for addressing contemporary challenges. By heeding their advice and implementing structural and cultural reforms, we can strive to create a political system that prioritizes the common good over partisan interests, honoring the vision of those who laid the nation’s foundations.

Unveiling the Political Party Affiliation of Your State's Governor

You may want to see also

Faction Risks: Parties were seen as factions, threatening unity and fostering conflict

The Founding Fathers of the United States, particularly George Washington and James Madison, were among the earliest and most vocal critics of political parties as factions. In his Farewell Address, Washington warned that parties could become "potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people." He saw factions as divisive forces that would prioritize partisan interests over the common good, threatening the fragile unity of the young nation. This perspective was rooted in the belief that a government should operate on principles of consensus and virtue, not the competing interests of organized groups.

Consider the mechanics of how factions operate within a government. When political parties form, they inherently create "us vs. them" dynamics, where loyalty to the party often supersedes loyalty to the nation. This can lead to legislative gridlock, as seen in modern governments where partisan bickering stalls critical policies. For instance, in the U.S. Congress, party-line voting has become the norm, with representatives frequently prioritizing party agendas over bipartisan solutions. This behavior undermines the collaborative spirit necessary for effective governance, illustrating the risks Washington and Madison foresaw.

To mitigate the risks of factions, Madison proposed a system of checks and balances in *Federalist No. 10*, arguing that a large, diverse republic would dilute the power of any single faction. However, this solution assumes a multiplicity of interests that prevent dominance by one group. In practice, two-party systems, like those in the U.S. and the U.K., often concentrate power in a way that exacerbates factionalism. For example, the winner-takes-all approach in many electoral systems encourages parties to polarize their bases, fostering conflict rather than unity. This highlights the unintended consequences of a system designed to manage factions but instead amplifies their influence.

A practical takeaway for modern governance is the need to incentivize cooperation over competition. One approach is to adopt electoral reforms, such as ranked-choice voting or proportional representation, which encourage candidates to appeal to a broader electorate rather than a narrow partisan base. Additionally, instituting bipartisan committees for key legislative tasks can foster collaboration. For instance, New Zealand’s Mixed-Member Proportional system has led to more coalition governments, reducing the dominance of single parties and promoting compromise. Such measures can help counteract the factional risks inherent in party politics.

Ultimately, the historical critique of political parties as factions remains relevant today. While parties can mobilize voters and structure political debate, their tendency to prioritize internal cohesion over national unity poses significant risks. By studying the warnings of early thinkers and implementing structural reforms, governments can strive to balance the benefits of organized politics with the need for unity and cooperation. The challenge lies in preserving the vitality of democratic participation without succumbing to the divisive tendencies of factionalism.

How Political Gerrymandering Shapes Districts and Influences Elections

You may want to see also

Corruption Fears: Parties were believed to prioritize power over public good, leading to corruption

The Founding Fathers of the United States, particularly George Washington and James Madison, expressed deep reservations about the rise of political parties. In his farewell address, Washington warned that parties could become "potent engines" of corruption, fostering division and undermining the public good. Madison, in Federalist Paper No. 10, acknowledged the inevitability of factions but feared their tendency to prioritize narrow interests over the common welfare. These concerns were rooted in the belief that parties, driven by the pursuit of power, would exploit government for personal or partisan gain rather than serve the people.

Consider the mechanics of party politics: once formed, parties often become self-perpetuating entities, incentivized to maintain power at all costs. This dynamic can lead to systemic corruption, as seen in historical examples like Tammany Hall in 19th-century New York. Boss Tweed and his associates used their party’s control to embezzle millions, illustrating how power consolidation within a party can erode accountability. Such cases validate the fears of early critics, who argued that parties would inevitably prioritize their survival over public service, creating fertile ground for graft and malfeasance.

To mitigate these risks, transparency and accountability mechanisms are essential. For instance, campaign finance reforms can limit the influence of special interests, while term limits reduce the incentive for politicians to entrench themselves in power. Citizens can also play a role by demanding greater disclosure of party finances and voting patterns. Practical steps include supporting nonpartisan watchdog organizations, participating in local government, and educating oneself on candidates’ records rather than party affiliations. These actions empower individuals to hold parties accountable and reduce the likelihood of corruption.

Comparatively, systems with weaker party structures, such as those in some European democracies, often exhibit lower levels of corruption. In these models, coalition governments force parties to negotiate and compromise, reducing the dominance of any single group. This contrasts sharply with two-party systems, where the winner-takes-all mentality can encourage extreme tactics to secure and maintain power. By studying these alternatives, we can identify structural reforms—like proportional representation or ranked-choice voting—that might diminish the corrupting influence of parties in government.

Ultimately, the fear that parties prioritize power over the public good is not merely historical but remains a pressing concern today. From gerrymandering to dark money in campaigns, modern examples abound of parties manipulating systems to their advantage. Addressing this requires both systemic changes and individual vigilance. By learning from past warnings and adopting proactive measures, we can strive to create a political environment where the public good, not partisan power, takes precedence.

The Great Political Shift: Did Parties Switch Ideologies Over Time?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$22.15 $23.99

$22.07 $24.95

Polarization Effects: Early critics argued parties would deepen ideological divides and gridlock governance

The Founding Fathers of the United States, particularly George Washington and James Madison, expressed deep reservations about the emergence of political parties. In his farewell address, Washington warned that parties could become "potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people." Madison, in Federalist No. 10, acknowledged factions as inevitable but feared parties would exacerbate them, leading to "an interested and overbearing majority" that stifles governance. Their concerns were rooted in the belief that parties would prioritize self-interest over the common good, fostering division rather than unity.

Consider the mechanics of polarization: when parties form, they naturally coalesce around distinct ideologies, creating an "us vs. them" dynamic. This binary framework simplifies complex issues, leaving little room for compromise. For instance, a study by the Pew Research Center shows that since the 1990s, the ideological gap between Democrats and Republicans has widened significantly, with 95% of Republicans more conservative than the median Democrat and vice versa. This polarization isn’t just ideological—it’s emotional, with 55% of Democrats and 49% of Republicans reporting they would be disappointed if a family member married someone from the opposing party. Such divisions erode the collaborative spirit necessary for effective governance.

To mitigate polarization, early critics like Washington and Madison would likely advocate for structural reforms. One practical step is to adopt ranked-choice voting, which encourages candidates to appeal to a broader electorate rather than just their base. Another is to eliminate partisan gerrymandering, which often creates safe districts that reward extremism. For individuals, fostering cross-partisan dialogue can help. Organizations like Braver Angels offer workshops where participants engage with those from opposing parties, reducing hostility and increasing understanding. These measures, while not foolproof, can chip away at the gridlock parties often create.

A comparative analysis of countries with multiparty systems reveals that while polarization exists, its effects are often less severe. In Germany, for example, coalition governments force parties to negotiate and compromise, reducing ideological rigidity. Contrast this with the U.S., where the two-party system amplifies extremes, leaving moderate voices marginalized. This isn’t to say multiparty systems are a panacea—Italy’s frequent government collapses illustrate the challenges of coalition-building—but they offer a different model for managing ideological diversity. The takeaway? System design matters, and the U.S. could learn from structures that incentivize cooperation over conflict.

Finally, the historical record shows that polarization isn’t just a modern phenomenon—it’s a recurring issue tied to the existence of parties. During the 1850s, partisan divisions over slavery led to the collapse of the Whig Party and the rise of the Republican Party, culminating in the Civil War. Today, issues like climate change and healthcare are similarly polarizing, with parties adopting rigid stances that hinder progress. To break this cycle, we must heed the warnings of early critics: prioritize national interests over party loyalty, embrace compromise, and reform systems that reward divisiveness. The alternative is a government perpetually gridlocked, unable to address the pressing challenges of our time.

Which President's Legacy Aligns with Your Political Party?

You may want to see also

Democracy Distortion: Parties were thought to manipulate voters, undermining true democratic representation

The Founding Fathers of the United States, including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, expressed deep reservations about political parties. In his farewell address, Washington warned that parties could become "potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people." They feared factions would prioritize their own interests over the common good, distorting the democratic process. This early critique highlights a persistent concern: parties, by their very nature, can manipulate voters through divisive rhetoric, misinformation, and emotional appeals, undermining the ideal of informed, rational decision-making in a democracy.

Consider the mechanics of party politics. Parties rely on simplifying complex issues into binary choices, often reducing nuanced debates to slogans and soundbites. This oversimplification manipulates voters by appealing to their emotions rather than their reason. For instance, during election campaigns, parties frequently use fear-mongering tactics, painting opponents as existential threats to sway undecided voters. Such strategies exploit cognitive biases, bypassing critical thinking and fostering polarization. When voters are manipulated into choosing sides based on fear or loyalty rather than policy, the democratic process becomes a contest of influence rather than a reflection of the people's will.

A comparative analysis of proportional representation systems versus winner-take-all systems reveals how party structures can distort democracy. In proportional systems, smaller parties gain representation, theoretically reflecting a broader spectrum of voter preferences. However, this can lead to coalition governments that prioritize compromise over decisive action, potentially alienating voters who feel their specific interests are diluted. In contrast, winner-take-all systems often result in two dominant parties that polarize the electorate, forcing voters into artificial choices. Both systems demonstrate how parties can manipulate the democratic process, either by fragmenting representation or by creating false dichotomies that exclude moderate voices.

To mitigate the distortion caused by party manipulation, practical steps can be taken. First, implement ranked-choice voting to allow voters to express nuanced preferences, reducing the pressure to align strictly with one party. Second, strengthen media literacy programs to educate citizens on identifying misinformation and emotional manipulation in political messaging. Third, encourage non-partisan redistricting to prevent gerrymandering, which parties use to secure unfair advantages. By addressing these structural and behavioral issues, democracies can move closer to their ideal of true representation, where voters make informed choices free from manipulative party tactics.

The Republican Party's Role in Ending Slavery in America

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Founding Fathers of the United States, particularly George Washington and James Madison, initially viewed political parties as harmful to the government. They believed parties would foster division, undermine unity, and prioritize faction interests over the common good.

George Washington opposed political parties because he feared they would create "factions" that would divide the nation, lead to conflicts, and distract from the principles of good governance. He warned against their dangers in his Farewell Address in 1796.

Yes, James Madison initially criticized political parties in the Federalist Papers, arguing they were dangerous to republican government. However, he later became a key figure in the Democratic-Republican Party, acknowledging their inevitability and potential to balance power in a large, diverse nation.

![Xi Jinping: The Governance of China: [English Language Version] by Xi Jinping (2015-02-17)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41DUOhgHfmL._AC_UY218_.jpg)