Political machines, which are organized networks of party leaders and loyalists that wield significant influence over local or regional politics, emerged primarily in the 19th century as a response to rapid urbanization, immigration, and the need for political patronage. While no single individual can be credited with their creation, key figures like Boss Tweed of Tammany Hall in New York City exemplify the rise of these systems. Tweed, who controlled Tammany Hall in the mid-1800s, perfected the machine model by exchanging jobs, favors, and services for political support, particularly among immigrant communities. Similar structures developed in other cities, driven by local leaders who capitalized on the era’s weak regulatory frameworks and the demand for social services. Thus, political machines were not invented by one person but evolved through the actions of opportunistic leaders in an era of political and social transformation.

Explore related products

$13.99 $15.75

$32.25 $39

What You'll Learn

- Boss Tweed's Tammany Hall: Infamous 19th-century New York machine, controlled by William Tweed, known for corruption

- Origins in Urbanization: Political machines emerged in growing cities to manage immigrant votes and patronage

- Role of Party Bosses: Powerful leaders like Tweed and Daley controlled machines, distributing jobs and favors

- Patronage Systems: Machines thrived by offering government jobs and services in exchange for political loyalty

- Decline and Reform: Progressive Era reforms and civil service laws weakened machines' influence in politics

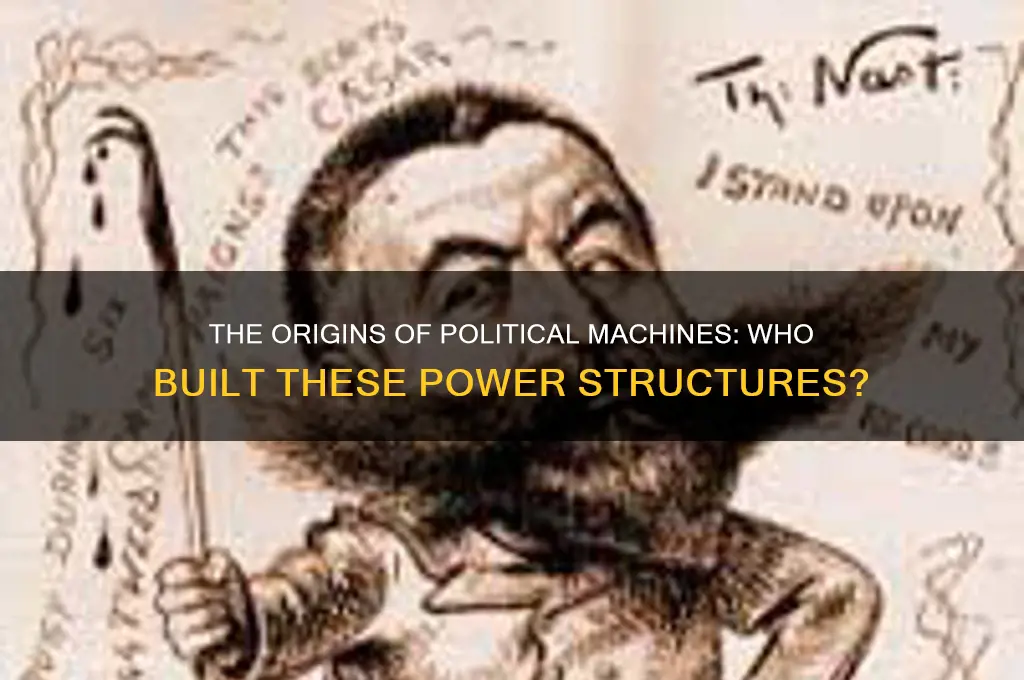

Boss Tweed's Tammany Hall: Infamous 19th-century New York machine, controlled by William Tweed, known for corruption

The concept of political machines, which are organized groups that control the political agenda and often engage in corruption, dates back to the 19th century in the United States. One of the most infamous examples of such a machine is Tammany Hall in New York City, which was controlled by William "Boss" Tweed. Tweed, a powerful and influential figure, rose to prominence in the mid-1800s and became the undisputed leader of Tammany Hall, the Democratic Party's political machine in New York. Under his leadership, Tammany Hall became a symbol of corruption, graft, and political manipulation, with Tweed at the helm orchestrating a vast network of patronage, bribery, and fraud.

Boss Tweed's Tammany Hall operated by exploiting the weaknesses of the 19th-century political system, particularly the lack of transparency and accountability. Tweed and his associates controlled access to government jobs, contracts, and favors, using these as tools to reward loyal supporters and punish opponents. They also manipulated elections through voter fraud, intimidation, and coercion, ensuring that Tammany Hall candidates won elections and maintained control over the city's government. The machine's influence extended to various levels of government, including the judiciary, police, and legislature, allowing Tweed to wield enormous power and influence over New York City's affairs. As a result, Tammany Hall became a byword for corruption, with Tweed's name becoming synonymous with political graft and malfeasance.

The corruption at Tammany Hall was not limited to local politics; it also had significant implications for the city's infrastructure, economy, and social welfare. Tweed and his associates embezzled millions of dollars from the city's treasury, using the funds to line their own pockets and reward their supporters. They also engaged in fraudulent real estate deals, inflated construction contracts, and other schemes that enriched themselves and their associates at the expense of the public. The most notorious example of this corruption was the construction of the New York County Courthouse, which was originally budgeted at $250,000 but ultimately cost over $13 million due to graft and embezzlement. This brazen display of corruption sparked public outrage and led to increased scrutiny of Tammany Hall's activities.

Despite the widespread corruption, Boss Tweed's Tammany Hall maintained a strong grip on New York City's politics for many years. Tweed's ability to deliver favors, jobs, and services to his constituents, particularly the city's immigrant population, helped to secure his power base. He also cultivated a carefully crafted public image, presenting himself as a generous and benevolent leader who cared about the needs of the common people. However, as the extent of the corruption became more widely known, public opinion began to turn against Tweed and Tammany Hall. The efforts of reformers, journalists, and cartoonists like Thomas Nast, who famously depicted Tweed as a symbol of corruption in his cartoons for Harper's Weekly, helped to expose the machine's misdeeds and galvanize public opposition.

The downfall of Boss Tweed and Tammany Hall began in the early 1870s, when a series of investigations and scandals exposed the extent of the corruption. In 1871, the New York Times published a series of articles detailing the machine's misdeeds, and a subsequent investigation by the state legislature led to Tweed's indictment on charges of corruption and embezzlement. Although Tweed initially evaded arrest and fled to Spain, he was eventually extradited back to the United States and sentenced to prison. The Tammany Hall machine, however, proved to be resilient, and despite Tweed's downfall, it continued to exert influence over New York City's politics for several more decades. Nevertheless, the legacy of Boss Tweed's Tammany Hall serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of political corruption and the importance of transparency, accountability, and ethical leadership in government.

Amplifying Your Political Voice: Why It's Essential for Democracy

You may want to see also

Origins in Urbanization: Political machines emerged in growing cities to manage immigrant votes and patronage

The origins of political machines are deeply intertwined with the rapid urbanization that characterized the 19th century, particularly in the United States. As cities like New York, Chicago, and Boston experienced explosive population growth due to industrialization and immigration, the political landscape became increasingly complex. Immigrants, often from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds, flooded into these urban centers in search of work and opportunity. This influx created a new and largely untapped pool of voters, but their integration into the political system was far from straightforward. Many immigrants faced language barriers, lacked familiarity with American political institutions, and were often marginalized by the native-born population. It was within this context that political machines emerged as a means to manage and mobilize these immigrant votes.

Political machines were essentially organized networks of party operatives who sought to control urban politics through a combination of patronage, clientelism, and grassroots mobilization. The creators of these machines were often ambitious politicians or party bosses who recognized the potential of immigrant communities as a powerful voting bloc. Figures like William Tweed in New York, known as "Boss Tweed," and Anton Cermak in Chicago exemplified this archetype. They built their machines by offering immigrants tangible benefits in exchange for political loyalty. These benefits included jobs, housing, legal assistance, and even basic necessities like food and coal during the winter months. By providing such services, machine bosses established themselves as indispensable intermediaries between immigrants and the government, effectively securing their votes and cementing their political power.

The rise of political machines was also facilitated by the structure of urban governance at the time. Cities were expanding rapidly, and local governments were often ill-equipped to handle the challenges of urbanization, such as sanitation, infrastructure, and public safety. Political machines filled this void by taking on the role of service providers, further solidifying their influence. For example, machine-controlled Tammany Hall in New York became synonymous with political patronage, distributing jobs and resources in exchange for electoral support. This system of reciprocity created a self-sustaining cycle: immigrants relied on the machine for assistance, and the machine relied on immigrants for votes, ensuring its dominance in urban politics.

The management of immigrant votes was a key function of political machines, and they employed various strategies to achieve this. Machine operatives, often referred to as "ward heelers," were assigned to specific neighborhoods to cultivate relationships with immigrant communities. They organized social events, provided translation services, and helped immigrants navigate bureaucratic processes. This personalized approach not only earned the trust of immigrants but also allowed machine bosses to monitor voting behavior and ensure compliance. Additionally, machines often controlled the polling places, using tactics like voter intimidation or fraud to secure favorable outcomes. While these methods were undemocratic by modern standards, they were effective in maintaining the machine's grip on power.

Patronage was another cornerstone of political machines, serving as both a tool for control and a means of rewarding loyalty. Machine bosses distributed government jobs, contracts, and favors to their supporters, creating a network of dependents who had a vested interest in the machine's continued success. This system of patronage extended beyond immigrants to include native-born citizens, business leaders, and other stakeholders. By controlling access to resources and opportunities, machine bosses could exert significant influence over urban politics and policy-making. However, this system also fostered corruption and inefficiency, as decisions were often driven by political expediency rather than public interest.

In conclusion, the emergence of political machines in growing cities was a direct response to the challenges and opportunities presented by urbanization and immigration. By managing immigrant votes and providing patronage, machine bosses established powerful networks that dominated urban politics for decades. While their methods were often controversial, they played a significant role in shaping the political landscape of American cities during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Understanding their origins in urbanization provides valuable insights into the dynamics of power, patronage, and representation in rapidly changing societies.

Switching Political Parties in Oregon: A Step-by-Step Guide to Changing Affiliation

You may want to see also

Role of Party Bosses: Powerful leaders like Tweed and Daley controlled machines, distributing jobs and favors

The concept of political machines is deeply intertwined with the rise of powerful party bosses who wielded significant influence over local and, in some cases, national politics. These individuals, often operating in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, created and controlled networks that became known as political machines. Among the most notorious figures in this context are William M. Tweed, also known as "Boss Tweed," and Richard J. Daley, both of whom exemplified the role of party bosses in shaping political landscapes.

William M. Tweed, the leader of Tammany Hall in New York City during the mid-1800s, is a quintessential example of a party boss who controlled a political machine. Tweed's machine was a well-oiled operation that relied on patronage, corruption, and the distribution of favors to maintain power. He controlled jobs, contracts, and even the judiciary, ensuring that his allies were rewarded and his opponents were marginalized. Tweed's machine was so powerful that it influenced elections, legislation, and the allocation of public resources, often at the expense of the public good. His ability to mobilize voters, particularly immigrants, through promises of jobs and favors, solidified his control over New York City politics.

Similarly, Richard J. Daley, who served as the mayor of Chicago from 1955 to 1976, was a dominant party boss who controlled the Cook County Democratic Party machine. Daley's machine was known for its efficiency in delivering services to constituents, but it also thrived on patronage and the strategic distribution of jobs and favors. He maintained a tight grip on the city's politics by rewarding loyalty and punishing dissent. Daley's machine was instrumental in securing votes, managing elections, and ensuring that the Democratic Party remained dominant in Chicago. His control extended to various levels of government, allowing him to influence policy and resource allocation in ways that benefited his machine and its supporters.

The role of party bosses like Tweed and Daley was not merely about personal power but also about maintaining the machinery of their political organizations. They acted as gatekeepers, deciding who received jobs, contracts, and other benefits. This system of patronage fostered a culture of dependency, where individuals and communities relied on the machine for their livelihoods and well-being. In return, the party bosses expected loyalty, votes, and support for their political agendas. This quid pro quo relationship was central to the functioning of political machines and ensured the bosses' continued dominance.

The impact of these party bosses extended beyond local politics, influencing state and national affairs. Their ability to mobilize large blocs of voters made them valuable allies for higher-level politicians seeking election or reelection. However, their methods often involved voter fraud, intimidation, and other unethical practices, raising questions about the legitimacy of the political processes they controlled. Despite the controversies, the legacy of party bosses like Tweed and Daley highlights the enduring influence of political machines in American history and the complex dynamics between power, patronage, and politics.

When Political Dissent Turns Destructive: Balancing Protest and Progress

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Patronage Systems: Machines thrived by offering government jobs and services in exchange for political loyalty

The concept of political machines is deeply intertwined with the patronage systems that emerged in the 19th century, particularly in urban areas of the United States. These machines were not created by a single individual but rather evolved as a response to the rapid urbanization, immigration, and industrialization of the time. Key figures like Boss Tweed of Tammany Hall in New York City exemplified how these systems operated. Tweed, who led Tammany Hall in the mid-1800s, perfected the art of exchanging government jobs, contracts, and favors for political loyalty and votes. This quid pro quo system became the backbone of political machines, ensuring their dominance in local and state politics.

Patronage systems thrived by leveraging the power of government resources to build networks of dependency and loyalty. Political machines would secure control over city or state governments and then distribute jobs, such as positions in the police force, sanitation department, or public works, to their supporters. These jobs were often given not based on merit but on loyalty to the machine. In return, recipients were expected to deliver votes for machine-backed candidates, attend rallies, and mobilize their communities during elections. This system created a cycle of dependency, where individuals relied on the machine for employment and the machine relied on them for political power.

The services provided by political machines extended beyond jobs to include direct assistance to constituents. Machines often acted as intermediaries between the government and the people, helping immigrants navigate bureaucratic systems, providing legal aid, and offering financial assistance during hard times. For example, Tammany Hall was known for distributing coal to the poor during winter and hosting community events. This hands-on approach made machines indispensable to their communities, fostering a sense of loyalty that translated into unwavering political support.

The creators and leaders of these machines, often referred to as "bosses," were adept at building and maintaining these patronage networks. Figures like George Washington Plunkitt of Tammany Hall openly discussed the distinction between "honest graft" (exploiting political connections for personal gain) and corruption, highlighting the blurred ethical lines within these systems. Their ability to control resources and deliver tangible benefits to their constituents solidified their power. However, this system also led to widespread corruption, as machines often prioritized their own interests over public welfare.

While political machines were not invented by a single person, their rise was facilitated by individuals who understood the power of patronage. These systems were particularly effective in cities with large immigrant populations, who often felt marginalized by mainstream politics. By offering jobs, services, and a sense of belonging, machines created a loyal base that sustained their influence for decades. The legacy of these patronage systems continues to shape discussions about political power, corruption, and the role of government in society.

Revolutionary Change: Do Political Parties Fuel or Hinder Progress?

You may want to see also

Decline and Reform: Progressive Era reforms and civil service laws weakened machines' influence in politics

The decline of political machines in American politics is closely tied to the Progressive Era reforms of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Political machines, which had been created and controlled by powerful bosses like Boss Tweed in New York City, had long dominated urban politics through patronage, corruption, and voter control. However, growing public dissatisfaction with machine politics, coupled with a push for government transparency and efficiency, set the stage for significant reforms that would weaken their influence.

One of the most impactful reforms during the Progressive Era was the introduction and expansion of civil service laws. Prior to these reforms, political machines thrived by rewarding loyalists with government jobs, a practice known as the spoils system. The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883 marked a turning point by establishing a merit-based system for federal government jobs, reducing the ability of machines to control appointments. Over time, similar reforms were adopted at the state and local levels, further limiting the machines' power to distribute patronage and maintain their networks of influence.

Progressive Era reformers also targeted the corrupt practices that sustained political machines, such as voter fraud and bribery. The introduction of secret ballots, voter registration requirements, and direct primary elections diminished the machines' ability to control the electoral process. These reforms empowered individual voters and reduced the reliance on machine bosses to mobilize and manipulate the electorate. Additionally, the rise of non-partisan reform groups, such as the Good Government Clubs, pressured local and state governments to adopt cleaner and more transparent political practices.

Another critical factor in the decline of political machines was the push for municipal reform. Progressives advocated for professional city management, often through the commission or council-manager forms of government, which replaced machine-controlled mayors and aldermen. These reforms shifted the focus from political patronage to administrative efficiency, further eroding the machines' grip on urban politics. Cities like Galveston, Texas, and Toledo, Ohio, became early adopters of these reforms, setting a precedent for others to follow.

Finally, the broader cultural and social changes of the Progressive Era contributed to the weakening of political machines. The rise of muckraking journalism exposed machine corruption to a wider audience, galvanizing public support for reform. Meanwhile, the growing influence of middle-class voters, who were less dependent on machine patronage, shifted the political landscape. As a result, the once-dominant political machines found themselves increasingly marginalized, unable to adapt to the new demands for accountability and transparency in government. By the early 20th century, while not entirely eradicated, their influence had significantly waned, marking a new era in American politics.

Are Political Parties Constitutionally Mandated? Exploring Legal Foundations

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The first notable political machine in the U.S. is often attributed to Boss Tweed and the Tammany Hall organization in New York City during the mid-19th century.

Boss Tweed, as the leader of Tammany Hall, perfected the political machine model by using patronage, corruption, and voter control to dominate New York City politics in the 1860s and early 1870s.

No, political machines have existed in various forms and countries. For example, similar systems emerged in cities like Chicago, Boston, and even in other nations where local power brokers controlled political processes.

Political machines gained power by providing services to immigrants and the working class in exchange for votes, using patronage to reward loyalists, and often employing intimidation or fraud to ensure electoral victories.

Yes, political machines often provided social services, jobs, and support to marginalized communities, particularly immigrants, who were otherwise neglected by mainstream political institutions.