The phrase who but Hoover political pin appears to be a cryptic or incomplete reference, likely blending historical and political elements. Herbert Hoover, the 31st President of the United States, is often associated with the Great Depression and his controversial political legacy. The term political pin could metaphorically refer to a symbol of blame, criticism, or a focal point of political scrutiny, as Hoover became a target for public frustration during his presidency. This phrase may invite exploration of how Hoover’s policies and leadership were pinned as central to the era’s economic crisis, sparking debates about accountability and the enduring impact of political decisions on public perception.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Hoover's Political Rise: Early career, Cabinet role, and path to presidency

- The Great Depression: Hoover's policies, economic impact, and public backlash

- Prohibition Era: Hoover's stance, enforcement challenges, and societal effects

- Election Loss: Campaign strategies, FDR rivalry, and defeat analysis

- Legacy and Criticism: Historical evaluation, achievements, and lasting controversies

Hoover's Political Rise: Early career, Cabinet role, and path to presidency

Herbert Hoover's political rise was marked by a combination of administrative prowess, humanitarian efforts, and strategic positioning within the Republican Party. His early career laid the foundation for his ascent, showcasing his ability to manage complex systems and respond to crises effectively. Born in 1874, Hoover pursued a career in geology and engineering, which took him around the world. His expertise in resource management and organizational skills became evident during World War I when he led the Commission for Relief in Belgium, a massive humanitarian effort that provided food to millions of war-affected Europeans. This role not only highlighted his administrative talents but also established him as a global figure of competence and compassion.

Hoover's transition into politics was accelerated by his appointment to President Warren G. Harding's cabinet in 1921 as Secretary of Commerce. This position allowed him to expand his influence beyond humanitarian work into the realm of economic policy and government administration. As Secretary of Commerce, Hoover championed the idea of "associationalism," encouraging cooperation between government and business to promote economic growth. He also focused on modernizing industry, improving living standards, and fostering international trade. His tenure was marked by innovation, such as promoting radio broadcasting and standardization in industry, which solidified his reputation as a forward-thinking leader. Hoover's cabinet role was a critical stepping stone, as it provided him with national visibility and experience in federal governance.

The path to the presidency was paved by Hoover's growing popularity and the endorsement of key Republican figures. After Harding's death in 1923 and the subsequent presidency of Calvin Coolidge, Hoover remained a prominent figure in the administration. His response to the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 further enhanced his public image, as he coordinated relief efforts with efficiency and empathy. By 1928, Hoover had become the Republican Party's nominee for president, running on a platform of continued prosperity and progressive reform. His campaign capitalized on the economic boom of the 1920s, often referred to as the "Coolidge Prosperity," and his own reputation as a problem-solver. Hoover's landslide victory in the 1928 election against Democrat Al Smith was a testament to his political rise, marking the culmination of his early career and cabinet achievements.

However, Hoover's presidency would soon be defined by the onset of the Great Depression, which began just months after his inauguration. Despite his earlier successes, his administration struggled to address the economic crisis, leading to a decline in his popularity. Nevertheless, his political rise remains a study in the importance of administrative skill, strategic positioning, and public service. From his early career in engineering to his pivotal cabinet role and eventual presidency, Hoover's trajectory illustrates how expertise and crisis management can propel a leader into the highest office, even if the challenges of governance ultimately test their legacy.

In summary, Herbert Hoover's political rise was characterized by his ability to navigate complex challenges, from humanitarian crises to economic policy. His early career in engineering and global relief efforts established his reputation, while his cabinet role as Secretary of Commerce provided the platform to showcase his administrative and innovative capabilities. The path to the presidency was a natural progression, fueled by his accomplishments and the support of the Republican Party. Hoover's story underscores the interplay between competence, opportunity, and public perception in the ascent to political power.

Terry Bradshaw's Political Shift: Did He Change Parties?

You may want to see also

The Great Depression: Hoover's policies, economic impact, and public backlash

The Great Depression, a period of severe economic downturn that began with the stock market crash of 1929, tested the leadership of President Herbert Hoover, whose policies and public image became central to the nation’s struggle. Hoover, initially seen as a competent engineer and humanitarian, faced unprecedented challenges as unemployment soared and economic activity plummeted. His administration’s response was rooted in a belief in voluntarism and limited government intervention, which would later prove insufficient to address the scale of the crisis. Hoover’s policies, though well-intentioned, were often criticized for being too modest and too reliant on private sector cooperation, failing to restore public confidence or stabilize the economy.

Hoover’s economic policies were characterized by a mix of government action and adherence to laissez-faire principles. He signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in 1930, which raised tariffs on over 20,000 imported goods, aiming to protect American farmers and industries. However, this move backfired as it triggered retaliatory tariffs from other nations, severely contracting international trade and exacerbating the global economic downturn. Additionally, Hoover increased federal spending on public works projects, such as the Hoover Dam, and established the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) in 1932 to provide loans to banks, railroads, and other businesses. Despite these efforts, the economy continued to deteriorate, with unemployment reaching nearly 25% by 1933. Hoover’s refusal to provide direct relief to individuals, fearing it would undermine self-reliance, further alienated the public.

The economic impact of Hoover’s policies was profound and largely negative. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff deepened the Depression by stifling global trade, while his reliance on voluntarism failed to prevent widespread bank failures and business closures. The RFC, though innovative, was underfunded and unable to stem the tide of economic collapse. The agricultural sector, already struggling before the Depression, was devastated as crop prices plummeted, leading to widespread foreclosures and rural poverty. Industrial production halved between 1929 and 1932, and wages fell sharply, leaving millions of Americans destitute. Hoover’s inability to reverse these trends eroded public trust in his leadership and in the capitalist system itself.

Public backlash against Hoover was fierce and multifaceted. As the Depression worsened, he became a symbol of government inaction and elitism. The Bonus Army march of 1932, in which World War I veterans demanded early payment of bonuses, was met with a forceful eviction ordered by Hoover, further damaging his reputation. The phrase “Who but Hoover?” became a rallying cry for critics, appearing on political pins and in protests, highlighting his perceived failure to address the nation’s suffering. The public’s frustration was evident in the 1932 election, where Hoover was overwhelmingly defeated by Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose promise of bold government intervention resonated with a desperate electorate.

In retrospect, Hoover’s policies were constrained by his ideological commitment to limited government and his underestimation of the Depression’s severity. While he took some unprecedented steps, such as creating the RFC and expanding federal spending, these measures were inadequate to combat the crisis. The public backlash against Hoover reflected not only his policy failures but also a broader shift in American attitudes toward the role of government in economic affairs. His legacy remains complex, viewed as both a leader who tried to navigate uncharted waters and a president whose actions were ultimately overshadowed by the magnitude of the Great Depression.

Are We Ready for a Second Political Party?

You may want to see also

Prohibition Era: Hoover's stance, enforcement challenges, and societal effects

The Prohibition Era, spanning from 1920 to 1933, was a defining period in American history marked by the legal prohibition of the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcoholic beverages. President Herbert Hoover, who served from 1929 to 1933, inherited the enforcement of the Volstead Act, which implemented the 18th Amendment. Hoover’s stance on Prohibition was complex; while he personally supported the law as a matter of respecting the Constitution, he acknowledged its enforcement challenges and societal consequences. Hoover once stated, “Our country has deliberately undertaken a great experiment... to reduce alcoholism and its devastating social consequences.” However, his commitment to upholding the law did not translate into effective enforcement, as the federal government lacked the resources and public support to combat widespread bootlegging and speakeasies.

Enforcement of Prohibition proved to be a monumental challenge. The sheer scale of illegal alcohol production and distribution overwhelmed federal agencies. The Bureau of Prohibition, tasked with enforcing the law, was understaffed and underfunded, making it difficult to police the vast network of bootleggers and smugglers. Additionally, corruption among law enforcement officials further undermined efforts, as many were bribed to turn a blind eye to illegal activities. Hoover’s administration attempted to strengthen enforcement by increasing penalties for violators and promoting public awareness campaigns, but these measures had limited impact. The rise of organized crime, led by figures like Al Capone, highlighted the unintended consequences of Prohibition, as criminal enterprises profited immensely from the illegal alcohol trade.

Societally, Prohibition had profound and often contradictory effects. While it was intended to reduce crime, poverty, and social ills associated with alcohol abuse, it instead fostered a culture of defiance and lawlessness. Speakeasies, clandestine establishments serving illegal alcohol, became popular gathering places, contributing to a vibrant but illicit nightlife. The era also saw a shift in drinking habits, with women and younger individuals participating more openly in alcohol consumption, challenging traditional social norms. However, Prohibition’s failure to achieve its goals led to widespread disillusionment with the law, eroding public trust in government institutions.

Economically, Prohibition had significant repercussions. The legal alcohol industry, a major source of tax revenue, was decimated, while the illegal market thrived. This loss of revenue, coupled with the costs of enforcement, strained government budgets. Moreover, the rise of organized crime syndicates created a parallel economy, further destabilizing communities. Hoover’s administration struggled to address these economic challenges, particularly as the Great Depression began in 1929, exacerbating the nation’s financial woes.

In conclusion, President Hoover’s approach to Prohibition reflected his commitment to upholding the law despite its inherent flaws and enforcement difficulties. The era’s societal and economic effects underscored the unintended consequences of such a sweeping legislative measure. Prohibition’s failure ultimately led to its repeal in 1933 with the passage of the 21st Amendment, marking a significant shift in American policy and public sentiment. Hoover’s tenure during this period highlights the complexities of enforcing unpopular laws and the enduring impact of Prohibition on American society.

Thomas Jefferson's Political Party: Unraveling His Democratic-Republican Legacy

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$11.99

$10.99

1932 Election Loss: Campaign strategies, FDR rivalry, and defeat analysis

The 1932 presidential election marked a pivotal moment in American political history, as incumbent President Herbert Hoover suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of Democratic challenger Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR). Hoover's campaign strategies, his rivalry with FDR, and the factors contributing to his loss are critical to understanding this election. Hoover's campaign was heavily burdened by the ongoing Great Depression, which had devastated the economy and left millions jobless. His messaging focused on individualism and limited government intervention, emphasizing his belief in voluntarism and self-reliance. However, these themes failed to resonate with a public desperate for immediate relief and government action. Hoover's attempts to highlight his administration's efforts, such as the creation of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, were overshadowed by the widespread suffering and perception of his detachment from the common man.

FDR's campaign, in stark contrast, offered a bold and hopeful vision encapsulated in his promise of a "New Deal." Roosevelt's strategy was to connect personally with voters, using fireside chats and charismatic speeches to project empathy and leadership. He criticized Hoover's handling of the Depression, arguing that the federal government had a moral obligation to intervene and provide relief. FDR's ability to inspire optimism, coupled with his pragmatic policy proposals, created a sharp contrast with Hoover's dour and defensive approach. The rivalry between the two candidates was not just ideological but also stylistic, with FDR's energetic campaigning further highlighting Hoover's perceived rigidity and aloofness.

Hoover's campaign was further hampered by his inability to effectively counter FDR's attacks. Roosevelt painted Hoover as indifferent to the plight of ordinary Americans, a narrative that stuck due to Hoover's insistence on maintaining a balanced budget and his reluctance to expand federal relief programs. The infamous "Who but Hoover?" political pins, which sought to blame Hoover for the nation's woes, became a symbol of public discontent. Hoover's attempts to shift blame onto external factors, such as the global economic downturn, were seen as excuses rather than solutions. His campaign lacked the emotional appeal and proactive messaging that FDR masterfully employed.

The defeat analysis reveals several critical factors. Firstly, Hoover's association with the onset of the Great Depression made him a scapegoat for the nation's troubles. Secondly, his campaign failed to adapt to the changing political landscape, sticking to traditional Republican principles that seemed out of touch with the crisis. Thirdly, FDR's superior political skills and ability to connect with voters on an emotional level played a decisive role. The election results, with FDR winning 472 electoral votes to Hoover's 59, underscored the public's desire for change and their rejection of Hoover's leadership.

In retrospect, Hoover's 1932 election loss was a culmination of economic calamity, ineffective campaign strategies, and a formidable opponent in FDR. His inability to address the public's demand for immediate relief, coupled with his perceived lack of empathy, sealed his fate. The election serves as a case study in how crises can redefine political priorities and how a candidate's messaging and persona can determine electoral success or failure. Hoover's defeat marked the end of an era and the beginning of a new chapter in American politics dominated by FDR's progressive vision.

The Bleak Reality: Why Politics Leaves Us Feeling Hopeless

You may want to see also

Legacy and Criticism: Historical evaluation, achievements, and lasting controversies

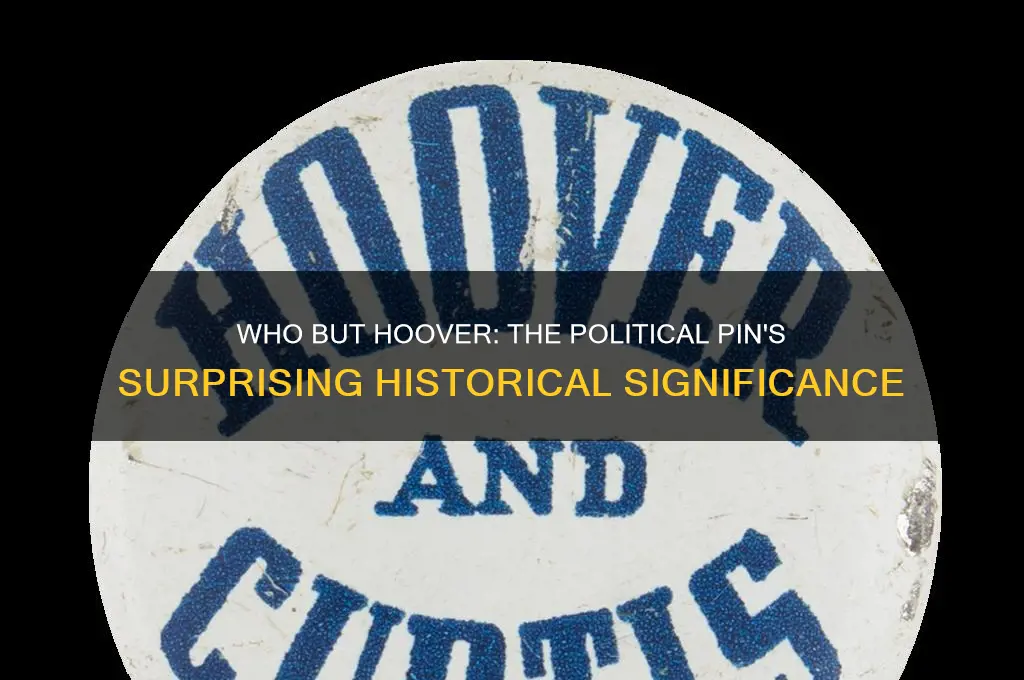

The "Who but Hoover" political pin, a relic from Herbert Hoover's 1928 presidential campaign, symbolizes both the optimism of the Roaring Twenties and the subsequent disillusionment of the Great Depression. Historically, Hoover's legacy is deeply intertwined with his presidency during one of America's most tumultuous periods. Initially celebrated as a humanitarian for his relief efforts in Europe after World War I, Hoover entered the White House with high expectations. His campaign pin, which rhetorically asked "Who but Hoover?" underscored the public's confidence in his administrative prowess and problem-solving abilities. However, the onset of the Great Depression in 1929 swiftly shifted public perception, casting Hoover as a symbol of governmental ineffectiveness in the face of economic catastrophe.

Hoover's achievements prior to the Depression are often overshadowed by the crisis that defined his presidency. As Secretary of Commerce under Presidents Harding and Coolidge, he championed efficiency in business and infrastructure development, earning him a reputation as a technocrat. His international relief work during and after World War I, particularly in feeding war-torn Europe, remains a significant humanitarian accomplishment. These successes contributed to the initial enthusiasm reflected in the "Who but Hoover" pin, which was designed to highlight his unparalleled qualifications for the presidency. Yet, the pin also became a bittersweet artifact, as the public's faith in Hoover's leadership eroded alongside the economy.

Historically, Hoover's handling of the Great Depression has been a focal point of criticism. His adherence to a limited government intervention approach, rooted in his belief in voluntarism and self-reliance, clashed with the escalating demands for federal relief. Programs like the Reconstruction Finance Corporation were seen as inadequate, and his opposition to direct federal aid to individuals exacerbated his image as out of touch with the suffering masses. The "Who but Hoover" pin, once a badge of trust, became ironic as critics questioned whether anyone but Hoover could have mismanaged the crisis so profoundly. This contrast between expectation and reality remains a central theme in evaluations of his legacy.

Despite the controversies, Hoover's post-presidential career offers a more nuanced view of his contributions. After leaving office, he became an influential voice on public policy, particularly during World War II, when he advised on food distribution and relief efforts. His work under the Truman administration further rehabilitated his reputation, showcasing his expertise in managing large-scale crises. However, the stigma of the Depression lingers, and historians continue to debate whether Hoover's actions were constrained by the political and economic realities of his time or were genuinely misguided. The pin, thus, serves as a historical marker of both the heights of public confidence and the depths of its disillusionment.

Lasting controversies surrounding Hoover's presidency include his perceived indifference to the plight of ordinary Americans and his inability to adapt his policies to the severity of the Depression. The "Who but Hoover" pin, while a campaign tool, has become a historical artifact that encapsulates the gap between leadership and public need. Modern evaluations often grapple with the question of whether Hoover was a victim of circumstance or a leader who failed to rise to the occasion. His legacy remains a cautionary tale about the limits of technocratic governance in the face of systemic crises, while also acknowledging his genuine contributions to public service. The pin, therefore, is not just a political relic but a symbol of the complexities of leadership and the enduring challenges of historical judgment.

Do Presidential Systems Limit Political Party Diversity?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A "who but Hoover political pin" is a campaign button or pin from the 1928 U.S. presidential election, promoting Herbert Hoover as the Republican candidate. The phrase "Who but Hoover?" emphasizes his popularity and inevitability as the next president.

The pin was significant because it symbolized Hoover's landslide victory in 1928, reflecting widespread public confidence in his leadership during a time of economic prosperity and optimism in the United States.

Yes, these pins are considered collectible items among political memorabilia enthusiasts. Their value depends on condition, rarity, and historical context, with well-preserved examples fetching higher prices.

You can find these pins at antique shops, online auction sites like eBay, or through specialized political memorabilia collectors and dealers.