The President of the United States has a wide range of powers and responsibilities, some of which are not explicitly granted by the Constitution. While the Constitution outlines key presidential roles, such as the power to sign or veto legislation, command the armed forces, grant reprieves and pardons, and receive ambassadors, there are two notable roles that have evolved through precedent and interpretation. Firstly, the President's role in exercising executive privilege, as seen in the Watergate scandal, is not directly addressed in the Constitution. Secondly, the Constitution does not expressly grant the President additional powers during times of national emergency, yet the structural design of the Executive Branch enables it to act swiftly in such situations. These two roles highlight the dynamic nature of presidential powers and the ongoing interpretation of the Constitution.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The President's power of privilege

The concept of executive privilege was first invoked by President George Washington in 1796, when he refused to provide the House of Representatives with documents related to the negotiation of the Jay Treaty with Great Britain. Washington argued that only the Senate played a role in the ratification of treaties, and thus the House had no claim to the material.

The precedent for executive privilege was further solidified by President Thomas Jefferson during the trial of Aaron Burr for treason in 1809. Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that the Sixth Amendment to the Constitution allowed for the protection of communications between the President and his advisors.

Executive privilege has since been invoked by several US Presidents, including Richard Nixon, Bill Clinton, and Donald Trump. Nixon attempted to use executive privilege to withhold evidence during the Watergate scandal, but the Supreme Court ruled that privilege was not absolute and ordered him to turn over the subpoenaed audio tapes. Similarly, Clinton attempted to assert privilege in the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal but lost in federal court.

Despite facing legal challenges, executive privilege remains a powerful tool for Presidents to protect sensitive information and maintain confidentiality in decision-making processes. However, its usage has evolved over time, with some Presidents, like Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, and Ronald Reagan, choosing to use it sparingly due to increased scrutiny and transparency expectations.

The USS Constitution: A Frigate with a Fighting Legacy

You may want to see also

The President's role in foreign affairs

The President of the United States has a significant role in foreign affairs. Article II of the Constitution establishes the executive branch of the federal government and vests executive power in the president. The President is responsible for the protection of Americans abroad and of foreign nationals in the United States. They decide whether to recognize new nations and new governments, and negotiate treaties with other nations, which become binding on the United States when approved by two-thirds of the Senate. The President may also negotiate executive agreements with foreign powers that are not subject to Senate confirmation.

The President, as Commander-in-Chief, has responsibility for directing the US Armed Forces, which has the second-largest nuclear arsenal. The power to declare war is constitutionally vested in Congress, but the President has ultimate responsibility for the direction and disposition of the military. The President also appoints ambassadors, other public ministers, and consuls.

Understanding ERISA: Funded Welfare Benefit Plans

You may want to see also

The President's power to grant reprieves and pardons

The President of the United States has the power to grant reprieves and pardons for federal offences, as outlined in Article II, Section 2, Clause 1 of the U.S. Constitution. This clause, also known as the Pardon Clause, gives the President the authority to grant clemency and pardon individuals convicted of crimes against the United States. The text of the clause states that the President "shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment".

A pardon is an expression of the president's forgiveness and is typically granted when the convicted person accepts responsibility for their crime and demonstrates good conduct after their conviction or completion of their sentence. While a pardon does not signify innocence, it does restore civil rights and reverse statutory disabilities that may have resulted from the conviction, such as firearm rights or occupational licensing issues. In rare cases, a pardon can also halt criminal proceedings or investigations and prevent an indictment, as seen in the case of Richard Nixon.

Reprieves and pardons were first used by President George Washington in 1795 when he granted amnesty to participants of the Whiskey Rebellion. Since then, the power to pardon has been used by presidents to grant amnesty for a wide variety of convictions and crimes. For example, Thomas Jefferson granted amnesty to citizens convicted under the Alien and Sedition Acts. The power to pardon is not restricted by any temporal constraints, except that the crime must have been committed while the president is in office.

The Supreme Court has interpreted the pardon power broadly, including the authority to grant conditional pardons, commutations of sentences, conditional commutations, remissions of fines and forfeitures, respites, and amnesties. The Court has also ruled that the president's pardon power is unlimited, except in cases of impeachment, and can be exercised at any time before, during, or after legal proceedings. However, there have been discussions and disagreements about how and where presidential pardons should be exercised. Some have argued that the pardon power should be vested in an executive authority, while others have proposed that the Senate should be involved in the process, especially in cases of treason.

To seek a pardon, an individual must submit a formal petition to the Pardon Attorney at the Department of Justice in Washington, D.C. The president can only grant pardons for federal offences, and convicted persons can only apply for a pardon five or more years after completing their sentence.

The Constitution's Continental Congress Adoption Date

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The President's role in appointing officials

The President of the United States has the power to appoint and remove executive officers, including Article III judges and other officers, with the advice and consent of the Senate. This power is derived from the Appointments Clause of the Constitution, which separates the powers of the president and the Senate in the appointment process. The President can also appoint inferior officers, such as heads of departments or members of advisory boards, without the need for Senate confirmation.

The Appointments Clause was created to prevent Congress from filling offices with their supporters and to ensure a measure of accountability in the appointment of important government positions. The President's power to appoint officers is limited by the requirement of Senate confirmation for certain positions, such as ambassadors, public ministers, consuls, and Supreme Court judges.

The number of votes needed to confirm a presidential nomination has changed over time. In 2013, the Senate changed the rules, requiring only a simple majority to end debate and bring a nomination to a vote, except for nominations to the Supreme Court, which could still be blocked by a filibuster. However, in 2017, the Senate rules were changed again to prevent filibusters for Supreme Court nominations.

The President's power to appoint and remove executive officers allows them to direct officials on how to interpret the law and make staffing decisions, subject to judicial review. This power is separate from the President's ability to grant reprieves and pardons for federal offences, which is explicitly stated in Article II of the Constitution.

Overall, the President's role in appointing officials is a significant aspect of their power and responsibility, allowing them to shape the federal government and direct the nation's diplomatic efforts.

The Constitution of South Africa: A Foundation for Freedom

You may want to see also

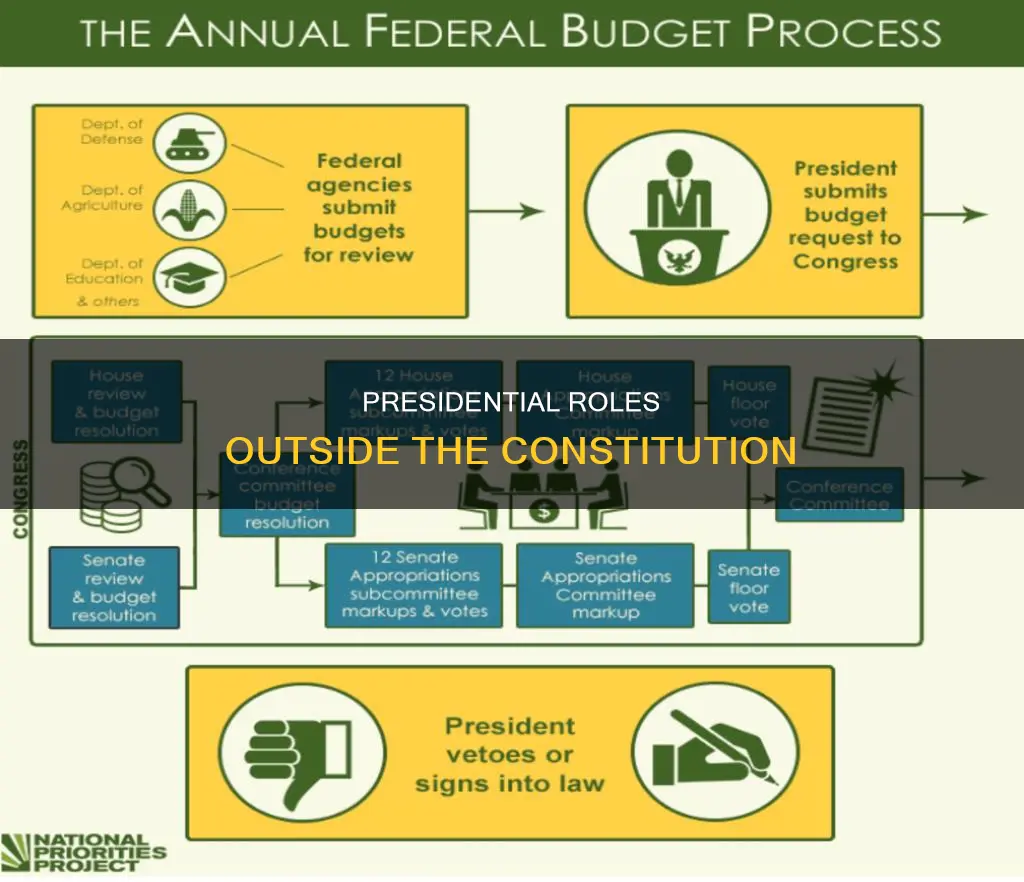

The President's role in national emergencies

The President of the United States has a wide range of powers and responsibilities, but the Constitution does not expressly grant additional authority in times of national emergency. However, the executive branch's structural design allows it to act faster than the legislative branch, implying that the Framers intended for the President to have certain emergency powers.

The National Emergencies Act outlines the President's authority during emergencies. It was passed in 1976 to address concerns about the scope of emergency powers. The Act requires the President to maintain records of orders and regulations made under emergency authority and report their costs to Congress. There are approximately 150 statutory emergency powers that the President can access upon declaring an emergency, with only 13 requiring a Congressional declaration.

The President's emergency powers are not unlimited. The Supreme Court has placed restrictions on their use, such as in the case of INS v. Chadha, where it held that a "Congressional termination" provision was an unconstitutional legislative veto. Additionally, the President's power to issue executive privilege during emergencies is not absolute, as seen in the Watergate scandal when the Supreme Court ruled against President Nixon.

In conclusion, while the Constitution does not explicitly grant the President additional powers in national emergencies, they have significant authority through various statutes and executive actions. The President's role is to coordinate and direct the nation's response, utilizing the statutory powers available to address the specific emergency at hand. The balance of power between the executive and legislative branches during emergencies remains a complex and evolving issue in American governance.

Revolutionary Constitution: A Radical Document?

You may want to see also