The forced removal of Indigenous children from their families and communities to attend residential boarding schools in Canada is a dark chapter in the country's history, primarily orchestrated by the Canadian government in collaboration with various Christian churches. While this tragic policy is often associated with Canada, it's important to note that a similar system existed in the United States as well. In Canada, the political party most closely tied to this policy is the Conservative Party, which held power during much of the period when the residential school system was in operation (from the late 19th century to the 1990s). The Canadian government, under various administrations, including those led by the Conservative Party, implemented and maintained these schools as part of a broader policy of assimilation, aiming to civilize and Christianize Indigenous children by stripping them of their language, culture, and traditions. This policy has had lasting and devastating effects on Indigenous communities, with intergenerational trauma still felt today.

Explore related products

$14.18 $28.95

What You'll Learn

- Historical Context: British colonial policies and their impact on indigenous education systems in India

- Residential Schools: Establishment, purpose, and conditions of boarding schools for Indian children

- Cultural Assimilation: Forced erasure of indigenous languages, traditions, and identities in these institutions

- Human Rights Violations: Physical, emotional, and sexual abuse suffered by children in the schools

- Long-Term Effects: Intergenerational trauma, loss of cultural heritage, and ongoing reconciliation efforts

Historical Context: British colonial policies and their impact on indigenous education systems in India

The British colonial era in India was marked by systematic efforts to dismantle indigenous education systems, replacing them with structures that served colonial interests. One of the most significant policies was the introduction of boarding schools, which aimed to assimilate Indian children into Western ideals while severing their ties to native cultures. These institutions were not merely educational but were tools of cultural erasure, designed to create a class of anglicized Indians who would perpetuate colonial rule. The Indian Education Service, established in 1856, formalized this approach, prioritizing English-medium education over traditional systems like the *gurukuls* and *madrasas*.

Analyzing the impact, the boarding school system targeted children from elite and tribal communities alike, often removing them from their families at a young age. For instance, the *Wood’s Dispatch* of 1854 laid the groundwork for a centralized education system that marginalized indigenous knowledge. Tribal children, in particular, were placed in institutions like the *Vanasramas*, which aimed to "civilize" them by stripping away their languages, customs, and spiritual practices. This policy was not just educational but deeply political, as it sought to weaken resistance to colonial authority by alienating younger generations from their roots.

A comparative perspective reveals that while the British justified these policies as "modernization," they were, in fact, acts of cultural imperialism. Unlike traditional Indian education, which was holistic and community-driven, colonial boarding schools emphasized rote learning, discipline, and loyalty to the Crown. The curriculum excluded subjects like Indian history, philosophy, or arts, effectively erasing centuries of intellectual heritage. This deliberate omission ensured that Indian children grew up disconnected from their identity, making them more pliable subjects of the empire.

Persuasively, it is crucial to recognize that the legacy of these policies persists today. The trauma inflicted on indigenous communities through forced assimilation continues to affect social structures, mental health, and cultural preservation. Efforts to revive traditional education systems, such as the *Eklavya* model residential schools for tribal children, are steps toward healing, but they face challenges due to decades of systemic neglect. Understanding this history is not just academic—it is essential for addressing contemporary inequalities and fostering inclusive education policies.

Practically, educators and policymakers can learn from this history by prioritizing culturally sensitive curricula and community involvement in schooling. For instance, integrating indigenous languages and knowledge systems into mainstream education can empower marginalized communities. Additionally, initiatives like teacher training programs that emphasize cultural awareness can bridge the gap between modern education and traditional values. By acknowledging the harms of colonial policies, India can move toward a more equitable and restorative educational framework.

The Rise of Political Parties in The Bahamas: A Historical Overview

You may want to see also

Residential Schools: Establishment, purpose, and conditions of boarding schools for Indian children

The establishment of residential schools for Indigenous children in Canada was a systematic effort rooted in colonial policies aimed at cultural assimilation. Initiated in the late 19th century, these schools were primarily the brainchild of the Canadian government, operating under the Conservative and Liberal parties at various times, with significant involvement from the Catholic and Protestant churches. The first residential school, the Mohawk Institute, opened in 1834, but the system expanded dramatically after the passage of the Indian Act in 1876, which granted the government control over Indigenous education. By the early 20th century, over 130 residential schools were operating across Canada, funded by federal policies that prioritized erasure of Indigenous cultures.

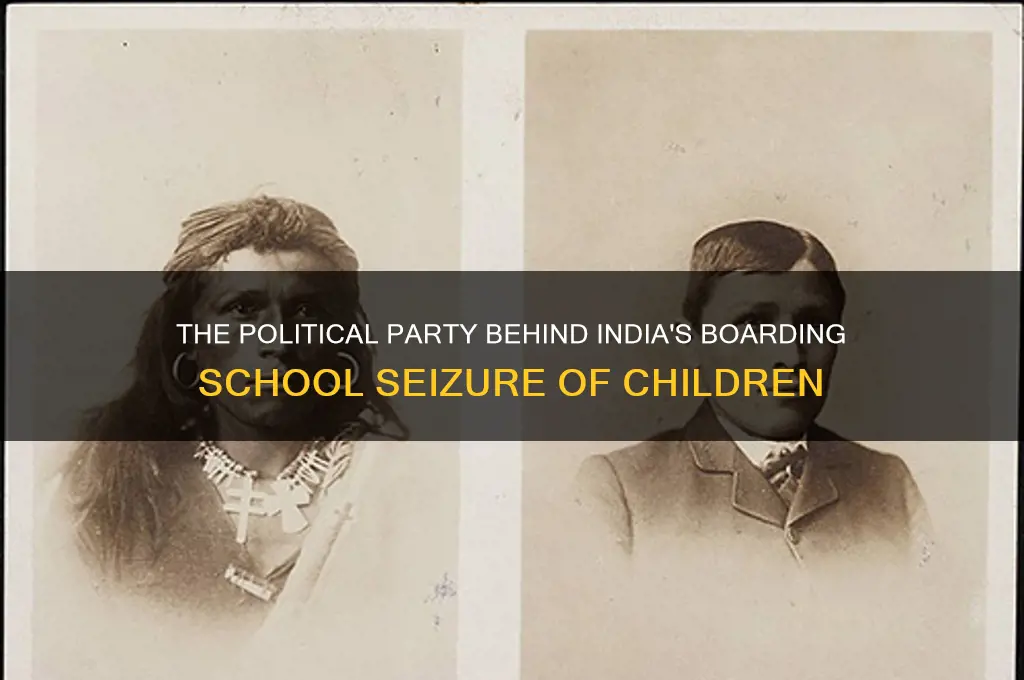

The stated purpose of these schools was to "civilize" Indigenous children by immersing them in Euro-Canadian culture, language, and religion. Officials like Duncan Campbell Scott, head of Indian Affairs in the early 1900s, openly declared the goal was to "kill the Indian in the child." Children were forcibly removed from their families, often under threat of legal repercussions for parents, and placed in institutions where they were forbidden to speak their native languages, practice their traditions, or maintain familial ties. This cultural genocide was framed as a benevolent act of education, yet the curriculum was rudimentary, focusing on manual labor for boys and domestic skills for girls, rather than academic advancement.

Conditions in residential schools were abysmal, marked by overcrowding, malnutrition, and inadequate medical care. Dormitories were often unheated, and children were dressed in ill-fitting, threadbare uniforms. Physical, emotional, and sexual abuse were rampant, perpetrated by staff and older students. Mortality rates were staggering; it is estimated that over 6,000 children died in these schools, though the true number may be higher due to incomplete records. Cemeteries on school grounds, often unmarked, bear silent witness to the tragedy. The last federally funded residential school closed in 1996, but the intergenerational trauma persists, affecting survivors and their descendants.

A comparative analysis reveals that while the Canadian government bore primary responsibility, the role of religious institutions cannot be overlooked. The Catholic Church, in particular, operated approximately 60% of these schools, yet has faced criticism for its reluctance to take full accountability or release records. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (2008–2015) documented these atrocities, issuing 94 Calls to Action, including calls for reparations and institutional reform. However, progress has been slow, underscoring the need for sustained political will and public pressure to address this dark chapter in Canadian history.

Practically, understanding this history requires engaging with survivor testimonies, such as those in the book *The Inconvenient Indian* by Thomas King or the documentary *We Were Children*. Educators and policymakers must prioritize Indigenous-led curricula and support community-based healing initiatives. For individuals, acknowledging this history means advocating for land acknowledgments, supporting Indigenous businesses, and amplifying Indigenous voices in media and politics. The legacy of residential schools is a call to action—one that demands both reflection and concrete steps toward reconciliation.

Army's Political Affiliation Inquiry: Fact or Fiction for Soldiers?

You may want to see also

Cultural Assimilation: Forced erasure of indigenous languages, traditions, and identities in these institutions

The Indian boarding school system, primarily orchestrated by the U.S. federal government and supported by both major political parties at various times, was a calculated assault on Indigenous cultures. These institutions, often run by religious organizations, systematically stripped children of their languages, traditions, and identities through forced assimilation. Upon arrival, children were stripped of traditional clothing, had their hair cut, and were forbidden to speak their native languages under threat of punishment. This cultural erasure was not a byproduct of the system but its core objective.

Example: The Carlisle Indian Industrial School, founded in 1879, became a model for this approach. Its motto, "Kill the Indian in him, and save the man," chillingly encapsulates the ideology driving these schools.

The methods employed were both insidious and brutal. Children were immersed in English-only environments, punished for speaking their native tongues, and taught to view their cultures as inferior. Traditional practices, from spiritual ceremonies to art forms, were banned. Analysis: This linguistic and cultural genocide aimed to sever Indigenous children from their communities, making them more "assimilable" into dominant white society. The trauma inflicted by this forced assimilation continues to reverberate through generations, contributing to higher rates of mental health issues, substance abuse, and cultural disconnection within Indigenous communities.

Takeaway: Understanding these tactics is crucial for recognizing the ongoing impacts of cultural erasure and the urgent need for revitalization efforts.

While the boarding school system is often associated with historical atrocities, its legacy persists. Comparative: Similar policies of forced assimilation were implemented in Canada, Australia, and other colonial contexts, demonstrating a global pattern of cultural genocide against Indigenous peoples. Practical Tip: Supporting Indigenous language revitalization programs, attending cultural events, and amplifying Indigenous voices are tangible ways to counter this legacy.

Caution: Be mindful of cultural appropriation and ensure engagement is respectful and informed.

The fight against cultural erasure is ongoing. Indigenous communities are reclaiming their languages, traditions, and identities through grassroots efforts, legal battles, and educational initiatives. Conclusion: Acknowledging the role of political parties and institutions in this historical injustice is essential, but true reconciliation requires active support for Indigenous self-determination and cultural revitalization.

Simone Biles' Political Party: Uncovering Her Affiliation and Views

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Human Rights Violations: Physical, emotional, and sexual abuse suffered by children in the schools

The Indian Residential Schools system, primarily orchestrated by the Canadian government in collaboration with various Christian churches, stands as a stark example of systemic human rights violations. Between the late 19th and late 20th centuries, over 150,000 Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families and placed in these institutions. While the stated goal was assimilation, the reality was a brutal regime of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse that left indelible scars on survivors and their communities.

Physical abuse was endemic within the residential school system. Children were subjected to harsh corporal punishment for speaking their native languages, practicing cultural traditions, or even minor infractions. Beatings with straps, rulers, and other objects were commonplace, often resulting in severe injuries. Malnutrition and inadequate medical care further exacerbated their suffering, with many children enduring chronic illnesses and physical disabilities as a result of their time in these schools. The lack of proper nutrition and healthcare not only stunted their physical development but also made them more vulnerable to diseases, some of which proved fatal.

Emotional abuse was equally pervasive, designed to strip children of their cultural identity and self-worth. They were forbidden to speak their Indigenous languages, forced to cut their hair, and dressed in uniforms that erased their cultural heritage. Verbal degradation and humiliation were routine, with staff often labeling children as "savages" or "inferior." This psychological assault led to widespread trauma, including anxiety, depression, and a profound sense of alienation from both Indigenous and non-Indigenous societies. The intergenerational impact of this emotional abuse continues to manifest in higher rates of mental health issues and substance abuse within Indigenous communities today.

Sexual abuse within the residential schools represents one of the most heinous aspects of this dark chapter in history. Both male and female children were victims of predatory staff and older students, with little to no recourse for justice. The trauma of sexual abuse has had long-lasting effects, including difficulties in forming healthy relationships, chronic PTSD, and a heightened risk of revictimization. The systemic nature of this abuse underscores the failure of the institutions and the government to protect the most vulnerable members of society.

Addressing these human rights violations requires a multifaceted approach. Acknowledgment of the atrocities committed is the first step, followed by meaningful reparations and support for survivors. Cultural revitalization programs, mental health services, and initiatives to strengthen Indigenous communities are essential in healing the wounds inflicted by the residential school system. By confronting this painful history and taking concrete actions to rectify its legacy, society can move toward reconciliation and justice for those whose childhoods were stolen.

The Political Party Behind Japanese Internment Camps in America

You may want to see also

Long-Term Effects: Intergenerational trauma, loss of cultural heritage, and ongoing reconciliation efforts

The forced removal of Indigenous children from their families to attend residential schools in Canada, primarily orchestrated by the Canadian government in collaboration with various Christian churches, has left an indelible mark on generations. This systemic policy, which spanned over a century, was not merely an educational initiative but a calculated effort to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture, eradicating their languages, traditions, and identities. The long-term effects of this policy are profound, manifesting as intergenerational trauma, cultural disconnection, and ongoing struggles for reconciliation.

Intergenerational trauma, a psychological phenomenon where the descendants of those who experienced profound trauma exhibit symptoms of distress, is a stark reality for many Indigenous communities. Studies show that survivors of residential schools often suffer from PTSD, depression, and anxiety, which they unconsciously pass on to their children through parenting styles, emotional availability, and even epigenetic changes. For instance, children of survivors are more likely to experience substance abuse, suicidal ideation, and difficulties in forming healthy relationships. Addressing this requires culturally sensitive mental health programs that incorporate traditional healing practices, such as smudging ceremonies and talking circles, alongside conventional therapies.

The loss of cultural heritage is another devastating consequence. Residential schools actively suppressed Indigenous languages, spiritual practices, and familial bonds, leaving many survivors unable to transmit their cultural knowledge to future generations. Today, efforts to revive languages like Cree, Ojibwe, and Inuktitut are underway, with immersion programs and digital resources playing a crucial role. However, the challenge lies in bridging the gap between elders who hold the knowledge and younger generations who may feel disconnected from their roots. Practical steps include integrating Indigenous history and language into public school curricula, funding community-led cultural initiatives, and creating intergenerational knowledge-sharing programs.

Reconciliation, though fraught with challenges, is an ongoing process that demands active participation from all Canadians. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action provide a roadmap, urging reforms in areas like child welfare, education, and justice. For individuals, reconciliation can start with small, meaningful actions: attending local Indigenous cultural events, supporting Indigenous-owned businesses, and educating oneself about the history and contemporary issues facing Indigenous peoples. Institutions must also take accountability by acknowledging their role in perpetuating harm and implementing policies that prioritize Indigenous voices and rights.

In conclusion, the legacy of residential schools is a complex tapestry of pain, resilience, and hope. By understanding the depth of intergenerational trauma, actively working to reclaim cultural heritage, and committing to meaningful reconciliation, society can begin to address the injustices of the past. This is not merely a moral imperative but a collective responsibility to ensure a more equitable and inclusive future for all.

Why Political Parties Matter: Shaping Policies, Societies, and Our Future

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Canadian government, under both the Conservative and Liberal parties, implemented and maintained the residential school system. The policy was initiated in the 19th century and continued until the late 20th century, with the federal government, not a single political party, being the primary enforcer.

Yes, the Conservative Party, particularly under Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, was instrumental in establishing the residential school system in the late 1800s. The policy aimed to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture.

Yes, the Liberal Party also played a significant role in maintaining and funding the residential school system throughout the 20th century, even after the Conservatives initiated it. Both major parties were complicit in the system's continuation.

In 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper, leader of the Conservative Party, issued a formal apology on behalf of the Canadian government for the residential school system. The Liberal Party, under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, has also acknowledged and addressed the legacy of the system through initiatives like the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.