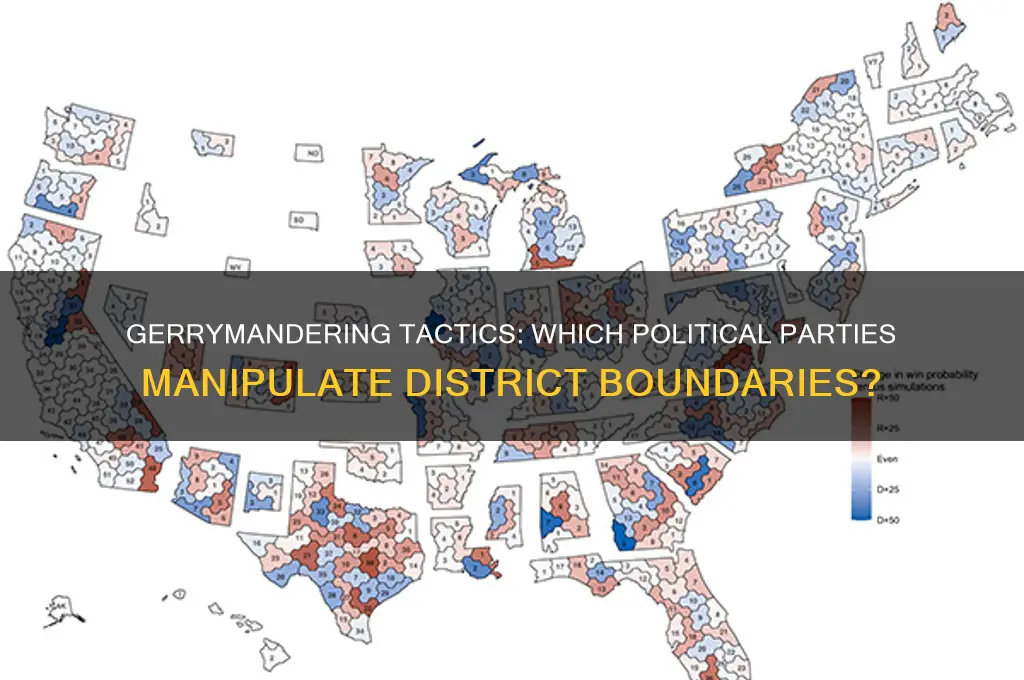

Gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating electoral district boundaries to favor a particular political party, has long been a contentious issue in American politics. While both major parties, the Democrats and the Republicans, have historically engaged in gerrymandering, recent decades have seen the Republican Party more frequently accused of employing this tactic to solidify their electoral advantages. This is particularly evident in states where Republicans control the redistricting process, allowing them to draw maps that dilute the voting power of Democratic-leaning constituencies, such as urban and minority communities. However, Democrats have also been criticized for gerrymandering in states where they hold redistricting authority, though their efforts are often less widespread due to the current political landscape. The debate over which party uses gerrymandering more frequently highlights the broader issue of partisan manipulation of electoral systems and its impact on fair representation.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Historical Use by Democrats: Examines Democratic Party's historical gerrymandering practices in various states

- Republican Gerrymandering Strategies: Explores GOP's modern tactics to redraw district lines for advantage

- State-Level Cases: Highlights specific states where both parties have engaged in gerrymandering

- Legal Challenges: Discusses court cases against gerrymandering by Democrats and Republicans

- Impact on Elections: Analyzes how gerrymandering by either party affects election outcomes

Historical Use by Democrats: Examines Democratic Party's historical gerrymandering practices in various states

The Democratic Party's historical engagement with gerrymandering reveals a complex tapestry of strategies employed across various states, often mirroring the political exigencies of their time. One notable example is the post-Reconstruction era in the South, where Democrats, seeking to consolidate power in the face of Republican and African American political gains, redrew district lines to dilute the influence of black voters. This practice, known as "racial gerrymandering," was particularly evident in states like Alabama and Mississippi, where convoluted districts were crafted to minimize the impact of the black electorate. The Supreme Court’s 1962 decision in *Baker v. Carr* paved the way for judicial intervention, but Democrats continued to exploit redistricting for decades, often under the guise of maintaining local representation.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Democrats in states like Illinois and Maryland refined their gerrymandering techniques to secure congressional majorities. Illinois, for instance, became a case study in partisan gerrymandering when Democrats redrew the 4th Congressional District, colloquially known as the "earmuff district," to connect two predominantly Hispanic areas with a thin strip of land. This design effectively marginalized Republican voters and ensured Democratic dominance in the region. Similarly, Maryland’s 2011 redistricting plan, orchestrated by Democrats, was so extreme that it led to a Supreme Court challenge in *Benisek v. Lamone*. While the Court declined to rule on the merits of partisan gerrymandering in that case, the map’s contorted shapes underscored the lengths to which Democrats would go to maintain political control.

A comparative analysis of Democratic gerrymandering practices reveals both regional and temporal variations. In the Northeast, Democrats often prioritized urban-rural divides, drawing districts that concentrated Republican voters in fewer areas while maximizing Democratic representation in densely populated cities. Pennsylvania’s 2002 redistricting, for example, was engineered by Democrats to protect incumbents and shore up their congressional delegation. Conversely, in the Midwest, Democrats focused on neutralizing Republican strongholds by splitting conservative communities across multiple districts. These strategies, while effective in the short term, often sparked public backlash and legal challenges, highlighting the ethical and practical dilemmas inherent in gerrymandering.

To understand the Democratic Party’s historical use of gerrymandering, it is instructive to examine the role of technology and legal frameworks. The advent of sophisticated mapping software in the late 20th century enabled Democrats to draw districts with surgical precision, a tool they wielded to great effect in states like North Carolina and Ohio. However, the Supreme Court’s evolving stance on gerrymandering, particularly in cases like *Gill v. Whitford* (2018) and *Rucho v. Common Cause* (2019), has complicated these efforts. While the Court has declined to set a standard for partisan gerrymandering claims, state-level reforms and independent redistricting commissions have emerged as countermeasures, forcing Democrats to adapt their strategies in an increasingly scrutinized landscape.

In conclusion, the Democratic Party’s historical gerrymandering practices reflect a strategic response to shifting political dynamics and technological advancements. From the racial gerrymandering of the post-Reconstruction South to the partisan manipulations of the late 20th century, Democrats have employed redistricting as a tool to secure and maintain power. While these efforts have often achieved their intended goals, they have also sparked legal challenges and public outcry, underscoring the contentious nature of gerrymandering. As the political landscape continues to evolve, the Democratic Party’s approach to redistricting will likely remain a subject of debate, shaped by both historical precedent and contemporary constraints.

How Political Parties Undermine Constitutional Integrity and Democratic Values

You may want to see also

Republican Gerrymandering Strategies: Explores GOP's modern tactics to redraw district lines for advantage

In the aftermath of the 2010 census, Republican-controlled state legislatures embarked on a systematic effort to redraw congressional and state legislative district lines, leveraging sophisticated data analytics and precise mapping technologies. This strategic gerrymandering aimed to consolidate Republican voter bases into safe districts while fracturing Democratic strongholds. For instance, in North Carolina, the GOP-led redistricting diluted urban Democratic votes by splitting cities like Asheville and Raleigh across multiple districts, ensuring Republican majorities in most. This tactic, known as "cracking," effectively minimized Democratic representation despite their substantial statewide support.

To maximize their advantage, Republicans employed a method called "packing," where they concentrated Democratic voters into a few districts, allowing them to win those seats by overwhelming margins while leaving surrounding districts safely Republican. Ohio serves as a prime example, where despite Democrats winning roughly half the statewide vote, Republicans secured nearly 75% of congressional seats in 2012. This imbalance persisted through multiple election cycles, demonstrating the enduring impact of these carefully crafted maps.

Modern Republican gerrymandering strategies also exploit demographic data to target specific voter groups. By analyzing racial, age, and socioeconomic data, GOP mapmakers have strategically diluted the influence of minority and young voters, who tend to lean Democratic. In Michigan, for example, districts were drawn to pack African American voters into a few urban districts, reducing their influence in neighboring areas. This precision, enabled by advanced software like Maptitude, ensures that even small shifts in voter behavior yield disproportionate Republican gains.

Critics argue that these tactics undermine democratic principles by prioritizing party advantage over fair representation. Legal challenges have emerged, with cases like *Rucho v. Common Cause* (2019) highlighting the difficulty of defining and regulating partisan gerrymandering. However, state-level reforms, such as independent redistricting commissions in Arizona and California, offer a counterbalance to partisan manipulation. For voters, understanding these strategies is crucial to advocating for transparency and fairness in the redistricting process.

Ultimately, Republican gerrymandering strategies reveal a calculated approach to maintaining political power through spatial engineering. While these tactics have proven effective in securing legislative majorities, they also spark debates about the integrity of electoral systems. As the 2020s redistricting cycle unfolds, the battle over district lines will continue to shape the political landscape, underscoring the need for vigilant oversight and reform.

The Political Party of President Andrew Johnson: Post-Lincoln Era

You may want to see also

State-Level Cases: Highlights specific states where both parties have engaged in gerrymandering

Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party over another, is not exclusive to a single party. Both Democrats and Republicans have engaged in this tactic at the state level, often leading to contentious legal battles and public outcry. To understand the bipartisan nature of gerrymandering, let's examine specific states where both parties have been implicated.

Pennsylvania stands as a prime example of bipartisan gerrymandering. In 2018, the state's Supreme Court struck down a Republican-drawn congressional map, deeming it an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. The court cited the map's excessive partisan advantage, which had allowed Republicans to secure 13 out of 18 congressional seats despite winning only 50% of the statewide vote. However, Pennsylvania's history also includes Democratic efforts to gerrymander. In the 1990s, Democrats controlled the redistricting process and drew maps that favored their candidates, demonstrating that both parties have exploited their power when given the opportunity.

North Carolina offers another illustrative case. Republicans have been accused of aggressive gerrymandering in recent years, with federal courts striking down both congressional and state legislative maps in 2016 and 2019 for unconstitutional racial and partisan bias. Yet, North Carolina Democrats are not innocent either. In the 1980s and 1990s, they drew maps that maximized their representation, showcasing a long-standing tradition of both parties manipulating districts for political gain. This back-and-forth highlights the cyclical nature of gerrymandering, where the party in power often seeks to entrench its advantage.

Maryland provides a clear example of Democratic gerrymandering. In 2012, Democrats redrew the state's 6th congressional district to unseat a Republican incumbent, diluting Republican votes across the district. This map survived legal challenges until 2019, when a federal court ruled it unconstitutional. While Maryland's recent gerrymandering has been primarily Democratic, Republicans have also engaged in similar tactics in the past, particularly at the state legislative level. This state exemplifies how gerrymandering can be a tool for whichever party holds the redistricting pen.

To address this issue, voters and advocates must push for nonpartisan or bipartisan redistricting reforms. States like California and Michigan have adopted independent commissions to draw district lines, reducing partisan influence. By studying these state-level cases, it becomes clear that gerrymandering is not a one-party problem but a systemic issue requiring structural solutions. Both Democrats and Republicans have demonstrated a willingness to manipulate districts when given the chance, underscoring the need for transparency and fairness in the redistricting process.

Understanding the Two Main Types of Political Parties and Their Roles

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$20.16 $24.99

Legal Challenges: Discusses court cases against gerrymandering by Democrats and Republicans

Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party over another, has sparked numerous legal battles across the United States. Both Democrats and Republicans have been accused of engaging in this tactic, leading to a series of high-profile court cases that challenge the constitutionality and fairness of such practices. These legal challenges often hinge on whether the redistricting violates the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment or the First Amendment’s freedom of association.

One notable case is *Gill v. Whitford* (2018), where Democrats in Wisconsin challenged the state’s Republican-drawn legislative map. The plaintiffs argued that the map was an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander, diluting Democratic votes. The Supreme Court, however, sidestepped the core issue by ruling that the plaintiffs lacked standing to bring the case. This decision highlighted the difficulty of establishing measurable harm in gerrymandering cases, leaving the door open for future challenges but offering little immediate relief.

In contrast, *Rucho v. Common Cause* (2019) involved Republican-drawn maps in North Carolina. Here, the Supreme Court ruled that federal courts lacked the authority to decide partisan gerrymandering claims, deeming them non-justiciable political questions. This decision effectively shielded partisan gerrymandering from federal judicial review, prompting critics to argue that it emboldened both parties to continue manipulating district lines without fear of federal intervention.

Despite these setbacks, state courts have emerged as critical battlegrounds. In *Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania v. League of Women Voters* (2018), the Pennsylvania Supreme Court struck down a Republican-drawn map as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander under the state constitution. This case demonstrated that state-level challenges, grounded in state constitutional protections, can succeed where federal efforts have faltered. Similarly, in *North Carolina State Conference of the NAACP v. Berger* (2022), the state Supreme Court invalidated a Republican-drawn map, though this decision was later overturned after a shift in the court’s composition.

These cases reveal a stark partisan divide in legal challenges to gerrymandering. Democrats have primarily targeted Republican-drawn maps, while Republicans have defended their redistricting efforts as lawful exercises of legislative power. The outcomes often depend on the ideological leanings of the judges hearing the cases, underscoring the politicized nature of these disputes. For voters and advocates, the takeaway is clear: combating gerrymandering requires a multi-pronged strategy, leveraging both federal and state legal frameworks, as well as public pressure to demand fairer redistricting processes.

Understanding the Frequency of Political Party Conventions in the U.S

You may want to see also

Impact on Elections: Analyzes how gerrymandering by either party affects election outcomes

Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party, has a profound and measurable impact on election outcomes. By strategically clustering or dispersing voters, parties can secure more seats than their overall vote share would suggest. For instance, in the 2012 U.S. House elections, Democrats won 1.4 million more votes nationwide than Republicans but still secured 33 fewer seats due to Republican-led gerrymandering in key states like Pennsylvania and Michigan. This disparity highlights how gerrymandering can distort democratic representation, amplifying one party’s power while marginalizing the other.

To understand the mechanics, consider a hypothetical state with 100 voters, 55 of whom support Party A and 45 Party B. If districts are drawn fairly, Party A might win 5 or 6 out of 10 seats. However, through gerrymandering, Party A could pack Party B voters into a few districts, ensuring overwhelming victories there, while spreading their own voters across the remaining districts to secure narrow wins. The result? Party A wins 7 or 8 seats despite having only 55% of the vote. This tactic, known as "cracking and packing," systematically dilutes the voting power of the opposing party’s supporters.

The impact isn’t just theoretical; it’s quantifiable. A 2019 study by the Brennan Center for Justice found that gerrymandering in states like North Carolina and Wisconsin gave Republicans a 10-15% advantage in seat share relative to their vote share. Conversely, in states like Maryland, Democrats have employed gerrymandering to similar effect, though the practice is often more associated with the party in power at the time of redistricting. These advantages can persist for a decade, as redistricting occurs only once every 10 years following the census, locking in political control regardless of shifting voter preferences.

The consequences extend beyond individual elections, shaping policy and governance. A party that secures a legislative majority through gerrymandering can advance its agenda with little regard for the will of the majority. For example, gerrymandered state legislatures have passed restrictive voting laws, redrawn congressional maps to further entrench their power, and blocked policies supported by a majority of voters. This undermines the principle of "one person, one vote" and erodes public trust in democratic institutions.

To mitigate these effects, reforms like independent redistricting commissions and judicial oversight are essential. States like California and Michigan have adopted such measures, leading to fairer maps and more competitive elections. While neither party is innocent in the use of gerrymandering, the solution lies in removing the power to draw districts from partisan hands. Until then, gerrymandering will continue to skew election outcomes, distorting the voice of the electorate and perpetuating political polarization.

The Mob's Political Ties: Uncovering Their Party Affiliations and Influence

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Both major U.S. political parties, Democrats and Republicans, have historically engaged in gerrymandering when in control of state legislatures, though the extent varies by state and election cycle.

No, gerrymandering is not exclusive to one party; both Democrats and Republicans have utilized it to gain political advantage in redistricting processes.

As of recent years, Republicans have been more frequently accused of gerrymandering due to their control of more state legislatures during the 2020 redistricting cycle, but Democrats have also engaged in the practice where they hold power.

Third parties and independents rarely engage in gerrymandering because they typically lack control of state legislatures, which are responsible for drawing district maps.