The Civil Rights Act of 1964, a landmark legislation that outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, faced significant opposition during its passage. While the bill garnered bipartisan support, the primary resistance came from the Southern Democrats, often referred to as the Dixiecrats. These conservative Democrats, deeply rooted in the segregationist policies of the South, vehemently opposed the Act, viewing it as a federal overreach that threatened their way of life. Led by figures like Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, they employed filibusters and other parliamentary tactics to delay its passage, reflecting the deep regional and ideological divides of the era. Their opposition underscored the complex interplay between federal authority and states' rights, as well as the enduring struggle for racial equality in the United States.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Party | Southern Democrats (Dixiecrats) |

| Primary Opposition | Opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 |

| Geographic Base | Southern states of the U.S. |

| Key Figures | Senators Strom Thurmond, Robert Byrd, and other Southern Democrats |

| Rationale for Opposition | Fear of federal overreach, concern for states' rights, and resistance to desegregation |

| Voting Behavior | Majority of opposition votes in Congress came from Southern Democrats |

| Long-Term Impact | Led to a realignment of the Democratic Party and the rise of the "Solid South" for Republicans |

| Historical Context | Part of the broader resistance to the Civil Rights Movement in the South |

| Ideological Stance | Conservatism, states' rights, and resistance to racial integration |

| Outcome | Despite opposition, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed with bipartisan support |

Explore related products

$38.27 $42.95

What You'll Learn

- Southern Democrats' Resistance: Many Southern Democrats opposed the Act, fearing it would disrupt segregationist policies

- States' Rights Argument: Opponents claimed the Act violated states' rights to regulate social and racial matters

- Filibuster Tactics: Southern senators led a 75-day filibuster to block the bill's passage

- Barry Goldwater's Stance: Goldwater voted against the Act, citing concerns over federal overreach into private business

- Public Opinion Divide: While widely supported nationally, the Act faced strong opposition in the South

Southern Democrats' Resistance: Many Southern Democrats opposed the Act, fearing it would disrupt segregationist policies

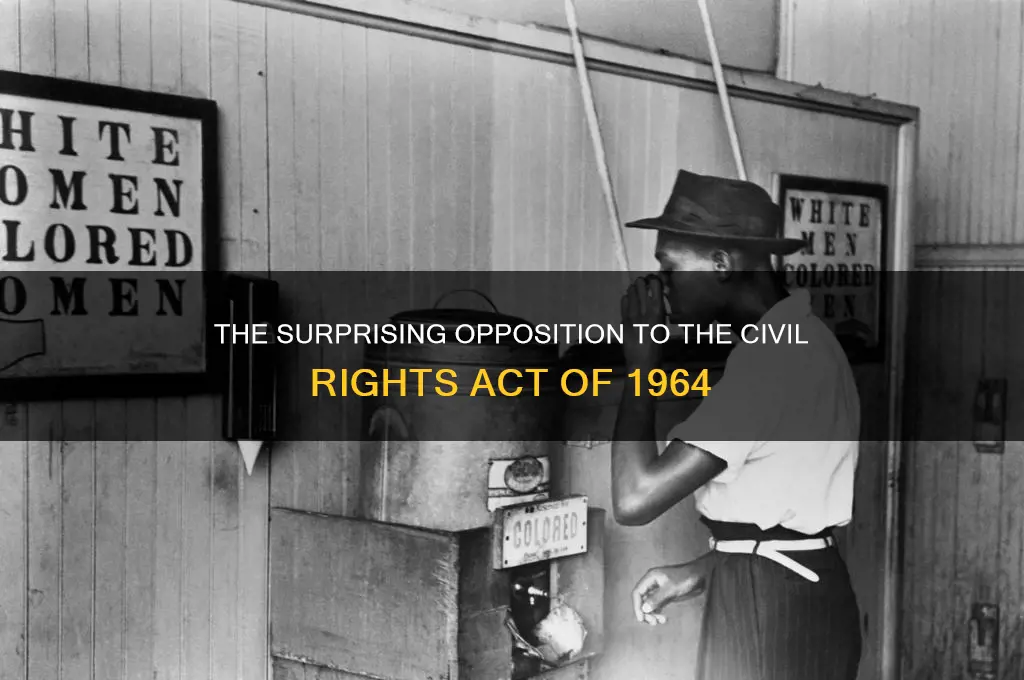

The Civil Rights Act of 1964, a landmark legislation aimed at ending segregation and discrimination, faced fierce opposition from a significant bloc of Southern Democrats. This resistance was rooted in a deep-seated fear that the Act would dismantle the segregationist policies that had long been the cornerstone of Southern society. These politicians, often referred to as "Dixiecrats," viewed the Act as a direct threat to their way of life, economic structures, and political power.

The Segregationist Mindset

Southern Democrats’ opposition was not merely political but ideological. For decades, segregation had been enforced through laws like the "Jim Crow" system, which maintained racial separation in schools, workplaces, and public spaces. The Civil Rights Act challenged this foundation by prohibiting discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. To these lawmakers, the Act represented federal overreach, infringing on states’ rights and upending a social order they believed was natural and necessary. Their resistance was fueled by a belief that integration would lead to economic competition, social unrest, and a loss of cultural identity.

Strategic Resistance and Filibuster

The opposition was not passive; it was strategic and relentless. Southern Democrats, led by figures like Senator Richard Russell of Georgia and Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, employed parliamentary tactics to delay the Act’s passage. The most notable was the filibuster, a procedural tool used to prolong debate and prevent a vote. This filibuster lasted 57 days, the longest in Senate history at the time. Their goal was to wear down supporters of the bill, but the filibuster ultimately failed, highlighting the growing national consensus in favor of civil rights.

Economic and Social Fears

Beyond ideology, Southern Democrats’ resistance was driven by practical concerns. They feared that desegregation would disrupt the region’s economy, which relied heavily on cheap labor and racial hierarchies. Integration of workplaces and public spaces threatened to alter power dynamics between employers and employees, as well as between white and Black citizens. Socially, the Act challenged deeply ingrained norms, prompting fears of racial mixing and cultural change. These anxieties were often stoked by politicians who portrayed the Act as an existential threat to Southern traditions.

Legacy of Resistance

The opposition of Southern Democrats to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 marked a turning point in American politics. While the Act eventually passed with bipartisan support, the resistance laid bare the deep divisions within the Democratic Party. Many Southern Democrats, disillusioned by their party’s embrace of civil rights, began to shift their allegiance to the Republican Party, a realignment that reshaped the political landscape for decades. Their resistance also underscored the enduring power of racial politics in American society, a reminder that progress often requires confronting entrenched systems of oppression.

In understanding this resistance, we see not just a historical footnote but a reflection of the complexities of change. The Southern Democrats’ opposition was a last stand for segregation, a futile yet revealing effort to preserve a dying order in the face of an inexorable march toward justice.

Stop Political Party Surveys: Effective Strategies to Regain Your Privacy

You may want to see also

States' Rights Argument: Opponents claimed the Act violated states' rights to regulate social and racial matters

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 faced fierce opposition from those who argued it overstepped federal authority and infringed upon states' rights to govern their own social and racial policies. This argument, rooted in the Tenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, posits that powers not explicitly granted to the federal government are reserved for the states. Opponents, primarily from the South, claimed the Act’s provisions—such as outlawing segregation in public accommodations and employment discrimination—were an unconstitutional intrusion into state sovereignty. This perspective was not merely a legal technicality but a deeply held belief that states should retain control over their internal affairs, particularly in matters of race.

To understand the states' rights argument, consider the historical context of the South’s resistance to federal intervention. For decades, Southern states had maintained Jim Crow laws, which enforced racial segregation and disenfranchised African Americans. The Civil Rights Act directly challenged these systems, and opponents framed their resistance as a defense of local autonomy rather than an endorsement of racial inequality. For instance, Senator Richard Russell of Georgia, a leading opponent, argued that the Act was “a blow directed at the very heart of the system of government American patriots established.” This rhetoric resonated with many Southerners who viewed federal enforcement as a threat to their way of life, even if that way of life was built on racial subjugation.

The states' rights argument was not without strategic calculation. By framing their opposition in constitutional terms, critics sought to shift the debate from morality to legality. This allowed them to appeal to a broader audience beyond the South, including conservatives and libertarians who prioritized limited federal power. However, this argument often masked the underlying racial motivations. For example, while states' rights were invoked to oppose desegregation, there was little outcry when the federal government intervened in other areas, such as interstate commerce or national defense. This inconsistency revealed the selective application of the states' rights principle to protect racial hierarchies.

Practical implications of the states' rights argument can be seen in the legislative tactics used to block the Act. Opponents employed filibusters, amendments, and procedural delays to stall its passage, leveraging their understanding of Senate rules to maximize state-level influence. This highlights the importance of procedural knowledge in political battles, as well as the enduring tension between federal and state authority in American governance. Today, echoes of this argument persist in debates over issues like voting rights and LGBTQ+ protections, demonstrating its lasting impact on political discourse.

In conclusion, the states' rights argument against the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a complex blend of legal theory, regional identity, and racial politics. While framed as a defense of constitutional principles, it served as a tool to preserve racial inequality under the guise of local control. Understanding this argument requires examining its historical context, strategic use, and ongoing relevance, offering insights into the enduring challenges of balancing federal power and state autonomy in the pursuit of justice.

Alabama's Governor: Unveiling the Political Party Affiliation in 2023

You may want to see also

Filibuster Tactics: Southern senators led a 75-day filibuster to block the bill's passage

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 faced fierce opposition, and at the heart of this resistance was a strategic filibuster led by Southern senators. This 75-day parliamentary maneuver aimed to stall the bill’s passage by exploiting Senate rules requiring unanimous consent to proceed to a vote. The filibuster, a tactic rooted in procedural delay, became a symbol of the South’s determination to preserve segregation and resist federal intervention in state affairs. By endlessly debating and proposing amendments, these senators sought to exhaust their opponents and derail the legislation.

Analytically, the filibuster was more than a procedural obstacle; it was a calculated political strategy. Southern Democrats, known as Dixiecrats, spearheaded this effort, leveraging their minority position to wield disproportionate power. Their goal was to highlight regional divisions and rally public support against the bill. By prolonging the debate, they aimed to expose the fragility of the coalition backing the Act, hoping to fracture its support. This tactic, while undemocratic in spirit, was a masterclass in exploiting legislative loopholes to defend entrenched interests.

To understand the filibuster’s impact, consider its practical mechanics. Senators like Richard Russell of Georgia and Strom Thurmond of South Carolina took turns speaking for hours, often reading irrelevant documents or repeating arguments to consume time. This required a relentless counter-effort from supporters, who had to maintain a quorum and respond to every point raised. For instance, Senator Thurmond’s record-breaking 24-hour speech remains a stark example of the lengths opponents went to obstruct progress. Such tactics tested the stamina and resolve of civil rights advocates, turning the Senate floor into a battleground of endurance.

Persuasively, the filibuster underscores the lengths to which some will go to preserve inequality. It was not merely a delay but a deliberate attempt to undermine a bill that sought to dismantle systemic racism. The Southern senators’ actions reveal a deep-seated resistance to change, framed as a defense of states’ rights but rooted in a desire to maintain white supremacy. This historical episode serves as a cautionary tale about the misuse of parliamentary procedures to thwart justice, reminding us that procedural fairness must never become a tool for oppression.

In conclusion, the 75-day filibuster against the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a defining moment in American legislative history. It exposed the fragility of democratic processes when confronted with determined opposition and highlighted the resilience required to enact meaningful change. While the filibuster ultimately failed to block the bill’s passage, it remains a powerful reminder of the challenges faced in the fight for equality. Understanding this tactic provides valuable insights into the complexities of political resistance and the enduring struggle for civil rights.

Understanding the Political Party Composition of the House of Representatives

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$7.95 $7.95

Barry Goldwater's Stance: Goldwater voted against the Act, citing concerns over federal overreach into private business

Barry Goldwater's opposition to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was rooted in his deep-seated belief in states' rights and limited federal government. As a Republican senator from Arizona, Goldwater voted against the Act, arguing that it represented an overreach of federal authority into the realm of private business. This stance, while controversial, reflected his libertarian-conservative ideology, which prioritized individual freedom and minimal government intervention. Goldwater's decision was not an isolated incident but part of a broader political strategy that would later define the modern conservative movement.

To understand Goldwater's position, consider the context of the 1960s. The Civil Rights Act aimed to end segregation in public places and prohibit employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. While these goals were widely supported by many Americans, Goldwater and his allies saw the Act as a dangerous precedent for federal power. They argued that the government had no right to dictate how private businesses operated, even if those businesses engaged in discriminatory practices. This perspective was not merely a defense of discrimination but a principled stand against what they perceived as an expansion of federal authority at the expense of states' rights and individual liberties.

Goldwater's opposition was also a calculated political move. By voting against the Act, he solidified his base of support among Southern conservatives and libertarians who shared his skepticism of federal intervention. This decision, however, came at a cost. It alienated moderate Republicans and contributed to his landslide defeat in the 1964 presidential election against Lyndon B. Johnson. Despite this, Goldwater's stance laid the groundwork for the "Southern Strategy," a political approach that would later help the Republican Party gain dominance in the South by appealing to voters who opposed federal civil rights policies.

From a practical standpoint, Goldwater's argument against federal overreach raises important questions about the balance between individual rights and collective welfare. While his stance emphasized the importance of limiting government power, it also highlighted the challenges of addressing systemic discrimination without federal intervention. For instance, without the Civil Rights Act, many private businesses would have continued to exclude African Americans and other minorities, perpetuating inequality. This tension between individual liberty and social justice remains a central debate in American politics, with Goldwater's position serving as a historical touchstone for those who prioritize states' rights over federal authority.

In retrospect, Goldwater's vote against the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was both a reflection of his ideological convictions and a strategic political decision. His concerns about federal overreach resonated with a segment of the American electorate but ultimately failed to gain widespread support. Today, his stance serves as a reminder of the complexities inherent in balancing individual freedoms with the need for equitable treatment under the law. While Goldwater's arguments may seem outdated in an era where federal civil rights protections are widely accepted, they continue to influence debates about the role of government in regulating private behavior.

Do Political Parties File Tax Returns? Unveiling Financial Accountability

You may want to see also

Public Opinion Divide: While widely supported nationally, the Act faced strong opposition in the South

The Civil Rights Act of 1964, a landmark legislation prohibiting discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, enjoyed broad national support. Polls from the era indicate that a majority of Americans, particularly in the North and West, favored its passage. However, this national consensus masked a deep and bitter divide, with the South emerging as the epicenter of fierce opposition. This regional disparity wasn’t merely a difference of opinion; it was a clash of ideologies rooted in history, economics, and cultural identity.

Consider the voting record in Congress. While the Act passed with significant bipartisan support, a striking pattern emerged: 80% of Republicans voted in favor, compared to only 63% of Democrats. But this seemingly partisan divide was geographically skewed. Southern Democrats, who dominated the region’s political landscape, overwhelmingly opposed the bill, with 70% voting against it. This wasn’t a reflection of the Democratic Party’s national stance but rather a manifestation of the South’s resistance to federal intervention in what they viewed as state and local matters.

The South’s opposition wasn’t confined to legislative chambers; it permeated public life. Governors like Alabama’s George Wallace and Mississippi’s Ross Barnett became vocal critics, framing the Act as an assault on states’ rights and Southern traditions. Local newspapers amplified these sentiments, portraying the legislation as a threat to the Southern way of life. Public demonstrations, ranging from peaceful protests to violent confrontations, further underscored the region’s defiance. For instance, in Birmingham, Alabama, Commissioner Bull Connor’s use of fire hoses and police dogs against civil rights demonstrators became a symbol of the South’s resistance.

This divide wasn’t merely about race; it was also about power and control. The South’s economy, still largely agrarian and dependent on cheap labor, relied on a racial hierarchy that the Act threatened to dismantle. White Southerners feared not only the loss of social dominance but also economic instability. This fear was exacerbated by a sense of cultural alienation, as many Southerners perceived the federal government as an external force imposing values foreign to their heritage.

Understanding this divide requires recognizing the complexity of public opinion. While the South’s opposition was vocal and organized, it wasn’t monolithic. Moderate voices within the region, though often overshadowed, supported the Act, recognizing its moral and practical necessity. Similarly, national support wasn’t uniform; pockets of resistance existed outside the South, particularly in areas with significant racial tensions. This nuanced landscape highlights the importance of context in interpreting public opinion, reminding us that even widely supported reforms can face entrenched opposition in specific regions or communities.

Brands and Beliefs: Navigating Political Stances in Business Strategy

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The majority of opposition to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 came from conservative Southern Democrats, often referred to as Dixiecrats.

The Republican Party largely supported the Civil Rights Act of 1964, with a higher percentage of Republicans voting in favor of it compared to Democrats.

Southern Democrats opposed the Act because it challenged segregationist policies and threatened their political power in the South, which was built on maintaining racial inequality.

Yes, a small number of conservative Republicans opposed the Act, but their opposition was overshadowed by the broader Republican support for the legislation.

Over time, the Democratic Party shifted away from its segregationist Southern wing, embracing civil rights as a core principle, while many Southern conservatives eventually aligned with the Republican Party.