Abraham Lincoln, one of the most revered figures in American history, was nominated for President by the Republican Party in 1860. At a time of deep national division over slavery and states' rights, the Republican Party emerged as a force advocating for the abolition of slavery in the territories and a stronger federal government. Lincoln's nomination at the 1860 Republican National Convention in Chicago marked a pivotal moment, as he represented the party's commitment to preserving the Union and addressing the moral and economic issues tied to slavery. His election as the 16th President of the United States would ultimately lead the nation through the Civil War and set the stage for the abolition of slavery with the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Party | Republican Party |

| Year Nominated | 1860 |

| Presidential Candidate | Abraham Lincoln |

| Vice Presidential Candidate | Hannibal Hamlin |

| Platform | Opposition to the expansion of slavery, emphasis on free labor, and support for internal improvements |

| Convention Location | Chicago, Illinois |

| Convention Dates | May 16-18, 1860 |

| Number of Ballots | 3 |

| Key Opponents (within party) | William H. Seward, Salmon P. Chase, Simon Cameron |

| Election Outcome | Won the 1860 presidential election |

| Presidency Term | March 4, 1861 – April 15, 1865 |

| Historical Context | Nominated during a time of deep national division over slavery and states' rights |

Explore related products

$8.95

$8.95

What You'll Learn

- Republican Party's Rise: Lincoln's nomination marked the Republican Party's first presidential victory

- Convention: Lincoln secured the nomination at the Republican National Convention in Chicago

- Key Supporters: Allies like Seward and Bates initially led but backed Lincoln

- Platform Focus: The party emphasized anti-slavery expansion and preserving the Union

- Opposition Split: Democratic Party division helped Lincoln win the election

Republican Party's Rise: Lincoln's nomination marked the Republican Party's first presidential victory

Abraham Lincoln’s nomination as the Republican Party’s candidate in the 1860 presidential election was a watershed moment in American political history. It marked the first time the fledgling Republican Party, founded just six years earlier in 1854, secured the nation’s highest office. This victory was not merely a triumph for Lincoln but a validation of the party’s platform, which staunchly opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories. The nomination process itself was strategic, with Lincoln emerging as a consensus candidate during the Republican National Convention in Chicago, where he outmaneuvered more prominent figures like William H. Seward and Salmon P. Chase. This tactical selection underscored the party’s ability to unite around a candidate who could appeal to both moderate and radical factions within its ranks.

The Republican Party’s rise was fueled by its ability to capitalize on the fracturing of the Democratic Party and the decline of the Whig Party. By the late 1850s, the Democrats were deeply divided over the issue of slavery, particularly its extension into western territories. The Whigs, meanwhile, had collapsed under the weight of internal disagreements. The Republicans filled this political vacuum by offering a clear, cohesive stance against the spread of slavery, which resonated with voters in the North. Lincoln’s nomination was the culmination of this strategic positioning, as the party harnessed growing Northern discontent with Southern political dominance and the institution of slavery.

Lincoln’s victory in 1860 was not just a personal achievement but a testament to the Republican Party’s organizational prowess and ideological clarity. The party’s platform, which included support for internal improvements, a protective tariff, and homesteading, attracted a broad coalition of voters, from urban workers to rural farmers. However, it was the party’s unwavering opposition to slavery that became its defining characteristic. Lincoln’s nomination signaled that the Republicans were not merely a regional party but a national force capable of challenging the established order. This shift in political power set the stage for the Civil War and the eventual abolition of slavery, cementing the Republican Party’s role as a transformative force in American history.

To understand the significance of Lincoln’s nomination, consider the practical implications of the Republican Party’s rise. For instance, the party’s success hinged on its ability to mobilize voters through grassroots campaigns, innovative use of newspapers, and a network of local organizations. Modern political campaigns can draw lessons from this approach by focusing on clear messaging, coalition-building, and leveraging media to reach diverse audiences. Additionally, the Republicans’ emphasis on moral and economic issues offers a blueprint for parties seeking to align their platforms with the values and needs of their constituents. By studying the strategies that propelled Lincoln and the Republicans to victory, contemporary political organizations can navigate today’s complex electoral landscape more effectively.

Finally, Lincoln’s nomination and the Republican Party’s first presidential victory serve as a reminder of the power of principled leadership and strategic vision. In an era marked by deep divisions, the Republicans demonstrated that a party could rise to prominence by championing a cause greater than itself. This historical example encourages modern political movements to prioritize unity, clarity of purpose, and a commitment to addressing the pressing issues of their time. As the Republican Party’s ascent shows, success in politics often requires not just winning elections but fundamentally reshaping the national conversation.

Christian Liberty Party: Gauging Political Support and Beliefs Among Leaders

You may want to see also

1860 Convention: Lincoln secured the nomination at the Republican National Convention in Chicago

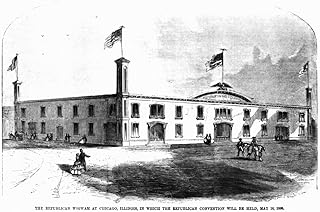

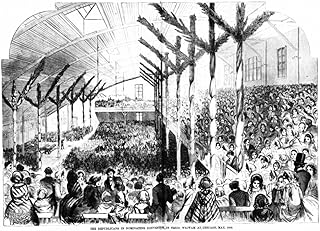

The 1860 Republican National Convention in Chicago was a pivotal moment in American political history, marking the rise of Abraham Lincoln from a relatively unknown Illinois politician to the party’s presidential nominee. Held in the Wigwam, a temporary wooden structure built specifically for the event, the convention drew delegates from across the North, all grappling with the divisive issue of slavery. Lincoln’s nomination was not a foregone conclusion; he faced stiff competition from more prominent figures like William H. Seward, Salmon P. Chase, and Simon Cameron. Yet, through a combination of strategic maneuvering, grassroots support, and a carefully crafted image as a moderate on slavery, Lincoln emerged victorious on the third ballot.

Lincoln’s success at the convention can be attributed to his campaign’s meticulous organization. His managers, led by David Davis, worked behind the scenes to secure delegates’ loyalty, often leveraging Lincoln’s humble origins and reputation as a skilled orator. Unlike Seward, whose outspoken antislavery views alienated some moderate Republicans, Lincoln’s nuanced stance—opposing the expansion of slavery without demanding its immediate abolition—appealed to a broader coalition. This positioning was critical in a party still defining its identity and seeking to unite Northern voters against the fractured Democratic Party.

The convention itself was a spectacle of political theater, with delegates from 17 states participating in heated debates and backroom deals. The Wigwam, capable of holding up to 10,000 people, buzzed with energy as supporters waved banners and chanted slogans. Lincoln’s nomination speech, delivered by his friend Norman Judd, emphasized his commitment to preserving the Union and his opposition to the spread of slavery, themes that resonated deeply with the audience. When his victory was announced, the crowd erupted in cheers, signaling the start of a campaign that would redefine American politics.

A comparative analysis of the 1860 convention reveals its uniqueness in the annals of presidential nominations. Unlike modern conventions, which are often scripted and ceremonial, the Chicago gathering was a genuine contest of ideas and personalities. Lincoln’s triumph was not just a personal achievement but a reflection of the Republican Party’s ability to navigate complex ideological differences. His nomination also foreshadowed the party’s future as a dominant force in national politics, particularly in the post-Civil War era. For historians and political strategists, the 1860 convention offers invaluable lessons in coalition-building, messaging, and the art of securing a nomination in a deeply divided field.

Practical takeaways from Lincoln’s nomination include the importance of grassroots organization and the strategic use of moderation in polarizing times. Modern political campaigns can learn from Lincoln’s team’s focus on delegate management and their ability to position him as a unifying figure. Additionally, the convention underscores the power of venue and spectacle in shaping public perception—the Wigwam, though temporary, became a symbol of democratic participation. For anyone studying political strategy, the 1860 Republican National Convention remains a masterclass in how to secure a nomination against formidable odds.

Rutherford B. Hayes' Political Party Affiliation Explained

You may want to see also

Key Supporters: Allies like Seward and Bates initially led but backed Lincoln

The 1860 Republican National Convention was a pivotal moment in American political history, and the role of key supporters like William H. Seward and Edward Bates cannot be overstated. These two prominent figures initially positioned themselves as frontrunners for the Republican presidential nomination. Seward, a senator from New York, was widely regarded as the leading candidate, having built a strong reputation as an abolitionist and a skilled politician. Bates, a former attorney general and judge from Missouri, also had a significant following, particularly among moderates who appreciated his balanced approach to the slavery issue.

As the convention unfolded, it became clear that while Seward and Bates had substantial support, their candidacies faced challenges. Seward's radical stance on slavery alienated some delegates, particularly those from the border states, who feared his nomination could exacerbate sectional tensions. Bates, on the other hand, struggled to unite the party, as his moderate views were seen as insufficiently committed to the cause of abolition by more fervent Republicans. Recognizing the need for a candidate who could bridge these divides, both men ultimately stepped aside, allowing Abraham Lincoln to emerge as a compromise candidate.

The strategic decision by Seward and Bates to back Lincoln was not merely an act of selflessness but a calculated move to ensure the party's unity and electoral success. Seward, in particular, played a crucial role behind the scenes, using his influence to sway delegates toward Lincoln. His experience and political acumen were instrumental in navigating the complex dynamics of the convention. Bates, though less involved in the maneuvering, lent his support to Lincoln, signaling to moderates that the party could rally around a candidate who balanced principle with pragmatism.

This shift in allegiance highlights the importance of coalition-building in political campaigns. Lincoln's nomination was not just a result of his own merits but also of the strategic decisions made by key supporters. By stepping aside, Seward and Bates demonstrated a rare willingness to prioritize the greater good of the party over personal ambition. Their actions underscore the often-unseen work of political allies in shaping outcomes, a lesson that remains relevant in modern campaigns.

In practical terms, this episode offers valuable insights for contemporary political strategists. First, it emphasizes the need to identify and cultivate key supporters who can influence delegate behavior. Second, it highlights the importance of flexibility and adaptability in the face of shifting political landscapes. Finally, it reminds us that successful nominations often depend on the ability to forge coalitions, even if it means setting aside individual aspirations. For anyone involved in political campaigns, studying the roles of Seward and Bates in Lincoln's nomination provides a masterclass in strategic thinking and collaborative leadership.

Building Political Movements: Can Parties Exist Without Running for Office?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Platform Focus: The party emphasized anti-slavery expansion and preserving the Union

The Republican Party, which nominated Abraham Lincoln for president in 1860, built its platform on two central pillars: preventing the expansion of slavery into new territories and preserving the Union. This dual focus was not merely a political strategy but a moral and constitutional imperative in a nation deeply divided over the issue of slavery. By emphasizing anti-slavery expansion, the party aimed to halt the spread of what many viewed as a morally repugnant institution, while its commitment to preserving the Union reflected a belief in the indivisibility of the American experiment.

Consider the historical context: the 1850s had seen the nation torn apart by debates over slavery in the territories, culminating in the Dred Scott decision and the fracturing of the Whig Party. The Republican Party emerged as a coalition of anti-slavery activists, former Whigs, and Democrats who opposed the expansion of slavery. Their platform was a direct response to the Democratic Party’s support for popular sovereignty, which allowed territories to decide the slavery question for themselves. By taking a firm stand against this expansion, the Republicans offered a clear alternative, appealing to Northern voters who saw slavery as both economically and morally wrong.

To understand the practical implications of this platform, examine the 1860 Republican Party convention. Lincoln’s nomination was no accident; his moderate stance on slavery—opposing its expansion but not calling for its immediate abolition—made him a unifying figure. The party’s platform explicitly stated, “the normal condition of all the territory of the United States is that of freedom,” a direct challenge to the pro-slavery forces. This language was not just rhetoric; it signaled a commitment to legislative action, such as passing laws like the Homestead Act and the Morrill Tariff, which indirectly supported the anti-slavery cause by promoting free labor and Northern economic interests.

A comparative analysis reveals the stark contrast between the Republican and Democratic platforms. While the Democrats focused on states’ rights and the protection of slavery, the Republicans framed their agenda as a defense of liberty and national unity. This framing was crucial in winning over undecided voters and solidifying Northern support. For instance, Lincoln’s Cooper Union speech in 1860 masterfully articulated the party’s position, arguing that preventing slavery’s expansion was essential to preserving the Union and fulfilling the Founding Fathers’ vision of equality.

In conclusion, the Republican Party’s emphasis on anti-slavery expansion and preserving the Union was not just a political tactic but a principled stance that shaped the course of American history. By focusing on these issues, the party not only secured Lincoln’s election but also laid the groundwork for the eventual abolition of slavery. This platform serves as a reminder of the power of moral clarity in politics and the enduring importance of unity in a diverse nation. Practical takeaways include the necessity of addressing divisive issues head-on and the role of leadership in bridging ideological divides.

Herbert Hoover's Political Affiliation: Unraveling His Party Association

You may want to see also

Opposition Split: Democratic Party division helped Lincoln win the election

The 1860 presidential election was a pivotal moment in American history, and Abraham Lincoln's victory can be largely attributed to the deep divisions within the Democratic Party. At the time, the Democratic Party was the dominant political force in the United States, but its internal conflicts over the issue of slavery proved to be its downfall. The party's inability to unite behind a single candidate created a power vacuum that allowed Lincoln, the Republican nominee, to emerge victorious.

The Democratic Party's Fracture: A Case Study in Disunity

Imagine a scenario where a major political party, instead of presenting a unified front, splits into multiple factions, each with its own candidate. This is precisely what happened to the Democrats in 1860. The party's national convention in Charleston, South Carolina, descended into chaos as delegates from the North and South clashed over the issue of slavery. The Southern delegates demanded a platform that explicitly protected slavery, while the Northern delegates sought a more moderate approach. This irreconcilable difference led to a walkout by the Southern delegates, who later convened their own convention and nominated John C. Breckinridge as their candidate. Meanwhile, the remaining Democrats nominated Stephen A. Douglas, a moderate who opposed the expansion of slavery but did not seek to abolish it. This division effectively split the Democratic vote, paving the way for Lincoln's victory.

A comparative analysis of the election results reveals the extent of the Democratic Party's self-inflicted damage. In the key states of Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Indiana, the combined Democratic vote (Douglas and Breckinridge) exceeded Lincoln's total, indicating that a unified Democratic Party could have potentially won these states. However, the split allowed Lincoln to secure victories in these critical battlegrounds, ultimately tipping the election in his favor. This example highlights the importance of party unity in electoral politics and serves as a cautionary tale for modern political parties.

Strategic Implications for Political Campaigns

For political strategists, the 1860 election offers valuable insights into the consequences of opposition division. When a dominant party fractures, it creates opportunities for smaller parties or candidates to capitalize on the resulting power vacuum. In Lincoln's case, the Republican Party, though relatively new, was able to present a unified front and capitalize on the Democrats' disarray. This strategy can be replicated in modern campaigns by identifying and exploiting divisions within opposing parties. For instance, targeted messaging that highlights these divisions can further exacerbate them, potentially leading to a split in the opposition vote.

To apply this strategy effectively, campaign managers should:

- Conduct thorough opposition research: Identify existing fault lines within the opposing party, such as ideological differences or personal rivalries.

- Develop targeted messaging: Craft messages that resonate with specific factions within the opposing party, amplifying existing tensions.

- Monitor opposition dynamics: Stay informed about developments within the opposing party, adjusting campaign strategies accordingly to exploit emerging divisions.

By understanding the dynamics of opposition division, political campaigns can develop more nuanced and effective strategies, increasing their chances of success. The 1860 election serves as a powerful reminder that sometimes, the key to victory lies not in one's own strength, but in the weaknesses of one's opponents.

The Rise of the GOP: Why Republicans Formed a New Party

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Republican Party nominated Abraham Lincoln for president in 1860.

No, Abraham Lincoln ran for president under the Republican Party, not the Whig Party, which had dissolved by the 1850s.

No, John C. Frémont was the first presidential nominee of the Republican Party in 1856, but Abraham Lincoln was the party's nominee in 1860.

No, Abraham Lincoln was exclusively nominated for president by the Republican Party in both 1860 and 1864.