The question of which political party engages in gerrymandering more frequently is a contentious and complex issue in American politics. Gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating electoral district boundaries to favor one party over another, has been employed by both Democrats and Republicans throughout history, though the extent and impact of these efforts often depend on which party holds power in state legislatures during redistricting cycles. While Republicans have been accused of more widespread and aggressive gerrymandering in recent years, particularly following the 2010 census, Democrats have also utilized the tactic in states where they control the redistricting process. Analyzing which party gerrymanders more requires examining specific state-level actions, legal challenges, and the resulting electoral outcomes, making it a nuanced debate rather than a straightforward answer.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Historical gerrymandering trends by party

Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party over another, has a long and contentious history in the United States. While both major parties have engaged in this tactic, historical trends reveal a nuanced pattern of usage and impact. In the early 19th century, when the term "gerrymander" was coined, both the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties manipulated districts to secure political advantage. However, as the two-party system evolved, the frequency and scale of gerrymandering shifted with the political landscape.

Analyzing the 20th century, it becomes evident that the Democratic Party dominated gerrymandering efforts in the early decades, particularly in the South. During the Jim Crow era, Democrats used redistricting to dilute the voting power of African Americans and maintain control in Southern states. This practice was not only about partisan gain but also about preserving racial segregation and white supremacy. For instance, in states like Alabama and Mississippi, Democrats drew districts that packed Black voters into as few districts as possible, minimizing their influence in state legislatures and Congress. This era underscores how gerrymandering intersected with broader systemic racism, making it a tool of oppression as much as political strategy.

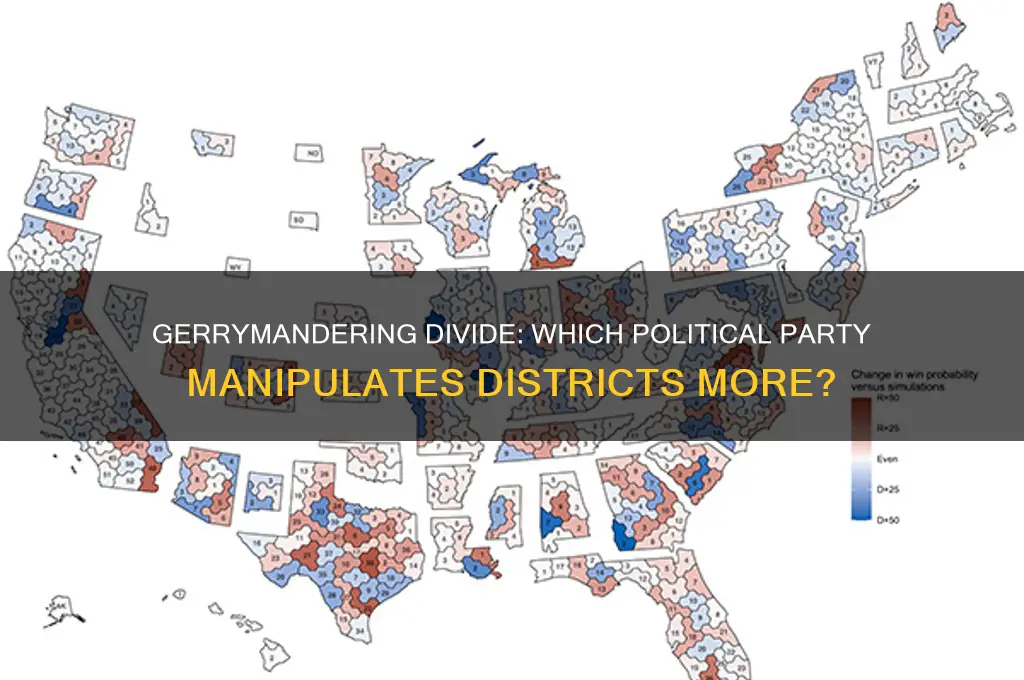

By contrast, the late 20th and early 21st centuries saw the Republican Party increasingly leveraging gerrymandering to solidify its power. Following the 2010 census, Republicans controlled redistricting in key states like Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Ohio, where they drew maps that maximized their congressional seats relative to their vote share. For example, in Pennsylvania, Republicans won 13 out of 18 congressional seats in 2012 despite receiving only 49% of the statewide vote. This strategic advantage was achieved through sophisticated mapping technologies and data analytics, allowing Republicans to create highly efficient gerrymanders that locked in their majority for years.

A comparative analysis reveals that while both parties have historically gerrymandered, the scale and impact have varied by era and region. Democrats' early 20th-century gerrymandering was deeply tied to racial disenfranchisement, whereas Republicans' modern efforts have focused on maximizing partisan advantage in a highly polarized political environment. This shift reflects broader changes in the parties' bases and strategies, with Republicans increasingly relying on rural and suburban voters, while Democrats have become more dependent on urban and minority voters.

To address these trends, reformers have proposed solutions like independent redistricting commissions, which have been implemented in states such as California and Arizona. These commissions aim to remove partisan bias from the redistricting process, though their effectiveness varies. For instance, California's commission has been praised for creating more competitive districts, while Arizona's has faced legal challenges over alleged bias. Practical tips for voters include staying informed about redistricting processes in their state, participating in public hearings, and supporting nonpartisan reform efforts. Understanding historical gerrymandering trends by party not only sheds light on past injustices but also informs strategies to create fairer electoral maps in the future.

Understanding International Politics: Global Relations, Power Dynamics, and Diplomacy Explained

You may want to see also

State-level gerrymandering comparisons

Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party over another, varies significantly at the state level. While both major U.S. parties engage in this tactic, evidence suggests that the Republican Party has been more aggressive in recent years, particularly following the 2010 census. This is partly due to their strategic focus on state legislatures, which control redistricting in most states. For instance, in North Carolina, Republican-drawn maps have consistently been challenged in court for diluting Democratic voting power, with the 2016 map deemed an unconstitutional racial gerrymander and the 2021 map facing similar scrutiny for partisan bias.

To understand the extent of this disparity, consider the efficiency gap, a metric used to measure gerrymandering by comparing the number of "wasted votes" for each party. In states like Ohio and Michigan, Republican-controlled redistricting has resulted in efficiency gaps that heavily favor GOP candidates, even when Democratic candidates win a majority of the statewide vote. For example, in 2018, Democrats in Wisconsin received 54% of the statewide vote but secured only 36% of the congressional seats, a clear indicator of partisan gerrymandering. These cases highlight how state-level control can be weaponized to entrench political power.

However, Democrats are not entirely absent from this practice. In states like Maryland and Illinois, Democratic-controlled legislatures have drawn maps that favor their candidates. Maryland’s 6th congressional district, for instance, was redrawn in 2011 to include heavily Democratic areas, flipping the seat from Republican to Democratic control. While these examples exist, the scale and impact of Democratic gerrymandering pale in comparison to Republican efforts, particularly in the post-2010 era. This imbalance is partly due to the GOP’s coordinated strategy through initiatives like REDMAP (Redistricting Majority Project), which targeted state legislative races to gain control of redistricting processes.

Practical efforts to combat gerrymandering have gained traction in some states. Independent redistricting commissions, as seen in California and Arizona, have successfully reduced partisan bias by removing map-drawing authority from state legislatures. Voters in states like Michigan and Colorado have also approved ballot measures to establish fairer redistricting processes. These reforms demonstrate that while gerrymandering remains a pervasive issue, state-level solutions can mitigate its effects. For activists and voters, advocating for independent commissions and supporting transparency in redistricting processes are actionable steps to address this problem.

In conclusion, state-level gerrymandering comparisons reveal a clear trend: Republicans have been more prolific and effective in leveraging redistricting to their advantage, particularly in the last decade. While Democrats have engaged in gerrymandering in certain states, the scope and impact of their efforts are significantly smaller. Understanding these disparities underscores the importance of state-level reforms, such as independent commissions and voter-led initiatives, to ensure fairer electoral maps. As redistricting cycles continue, the battle against gerrymandering will remain a critical focus for preserving democratic integrity.

Legally Launching Your Political Party: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Court cases involving partisan redistricting

The Supreme Court's 2019 ruling in *Rucho v. Common Cause* marked a significant turning point in the legal battle over partisan gerrymandering. By a 5-4 vote, the Court held that claims of partisan gerrymandering present nonjusticiable political questions, effectively removing federal courts from the process of policing redistricting maps drawn for partisan advantage. This decision left state courts and legislatures as the primary arbiters of redistricting fairness, but it also sparked a wave of state-level litigation and reform efforts. For instance, in *Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania (2018)*, the state’s Supreme Court struck down a Republican-drawn map as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander, redrawing it to create a more balanced representation. This case exemplifies how state courts can step in where federal oversight falls short, though the lack of uniform standards across states creates inconsistencies in how gerrymandering is addressed.

One of the most instructive cases in this arena is *Gill v. Whitford* (2018), which reached the Supreme Court but was ultimately dismissed on standing grounds. The plaintiffs argued that Wisconsin’s Republican-drawn map violated the First Amendment and the Equal Protection Clause by diluting Democratic votes through "packing and cracking" techniques. While the Court avoided ruling on the merits, the case highlighted the complexity of measuring partisan gerrymandering. The plaintiffs’ use of the "efficiency gap" metric—a statistical tool to quantify wasted votes—was both innovative and controversial. Critics argued it favored Democrats, while proponents saw it as a necessary tool for objectivity. This case underscores the challenge of developing a judicially manageable standard for partisan gerrymandering, a problem that remains unresolved.

A comparative analysis of *Vieth v. Jubelirer* (2004) and *League of United Latin American Citizens v. Perry* (2006) reveals the Supreme Court’s struggle to address partisan gerrymandering claims. In *Vieth*, the Court deadlocked 4-1-4, with Justice Kennedy arguing that a manageable standard for identifying unconstitutional gerrymanders might exist but was not yet presented. Two years later, in *LULAC*, the Court struck down a portion of Texas’s Republican-drawn map as a racial gerrymander but upheld the rest, even though partisan motives were evident. These cases illustrate the Court’s reluctance to intervene in partisan redistricting, often prioritizing procedural hurdles over substantive fairness. They also highlight the interplay between racial and partisan gerrymandering, as both often serve similar goals of entrenching political power.

Persuasive arguments for judicial intervention in partisan gerrymandering cases often center on the erosion of democratic principles. In *Benisek v. Lamone* (2018), Maryland Republicans challenged a Democratic-drawn map that flipped a historically Republican district. While the Supreme Court remanded the case on procedural grounds, the district court’s initial ruling found the map unconstitutional, citing the First Amendment’s protection against retaliatory vote dilution. This case demonstrates how partisan gerrymandering can suppress political speech and association, core tenets of democracy. Advocates argue that courts must act to prevent such abuses, as unchecked gerrymandering undermines the principle of "one person, one vote" and distorts electoral outcomes.

Finally, a descriptive look at *North Carolina v. Covington* (2022) reveals the ongoing tension between state and federal authority in redistricting disputes. After the state’s Republican-controlled legislature passed a map that heavily favored their party, the state Supreme Court struck it down as unconstitutional. However, the U.S. Supreme Court intervened, staying the decision and allowing the map to be used in the 2022 midterms. This case exemplifies the political and legal whiplash that can occur when state and federal courts clash over redistricting. It also highlights the role of timing and procedural tactics in these disputes, as delays in court rulings can effectively moot challenges until the next redistricting cycle.

In conclusion, court cases involving partisan redistricting reflect a complex interplay of legal, political, and constitutional principles. While federal courts have largely stepped back from adjudicating these claims, state courts and legislative reforms have emerged as critical battlegrounds. The lack of a clear, judicially manageable standard for partisan gerrymandering leaves the issue ripe for continued litigation and innovation. For those seeking to challenge or reform redistricting practices, understanding these cases provides a roadmap for navigating the legal and political landscape.

Exploring Alberta's Political Landscape: A Comprehensive Guide to All Parties

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact of voter suppression tactics

Voter suppression tactics, often intertwined with gerrymandering, systematically disenfranchise specific demographics, tilting electoral outcomes in favor of the party employing them. While both major U.S. parties have historically engaged in such tactics, recent data and legal challenges highlight a disproportionate use by the Republican Party. For instance, a 2020 Brennan Center analysis found that 25% of voting-age Black citizens and 23% of Hispanic citizens were purged from voter rolls in states with a history of racial discrimination, compared to 15% of white citizens. These purges, strict voter ID laws, and reduced polling places disproportionately affect Democratic-leaning voters, amplifying the impact of gerrymandering in these regions.

Consider the mechanics of suppression: in states like Georgia and Texas, Republican-led legislatures have enacted laws limiting mail-in voting and early voting hours, tactics that disproportionately affect urban, minority-heavy areas. These measures, coupled with gerrymandered districts, create a two-pronged attack on Democratic voting power. For example, in Georgia’s 2020 election, counties with high Black populations faced wait times averaging 51 minutes, compared to 6 minutes in predominantly white counties. Such barriers not only suppress individual votes but also discourage participation, diluting the collective power of targeted groups.

To combat these tactics, activists and organizations must focus on three actionable steps: first, challenge restrictive laws in court, as seen in the successful overturning of North Carolina’s voter ID law in 2020. Second, educate voters on their rights and provide resources like free ID assistance programs. Third, advocate for federal legislation like the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, which would restore preclearance requirements for states with a history of discrimination. Without such interventions, the combined effects of gerrymandering and suppression will continue to skew representation, undermining democratic integrity.

The psychological impact of voter suppression cannot be overlooked. When voters face repeated barriers, they internalize a sense of powerlessness, reducing turnout in future elections. This "chilling effect" compounds the advantages gained through gerrymandering, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of disenfranchisement. For instance, in Wisconsin, where Republican gerrymandering has locked in legislative majorities, voter turnout in predominantly Democratic districts dropped by 12% between 2012 and 2020, compared to a 4% decline statewide. This erosion of civic engagement is not just a statistical anomaly—it’s a deliberate strategy to maintain political dominance.

Ultimately, the impact of voter suppression tactics extends beyond individual elections, reshaping the political landscape in favor of those who employ them. While gerrymandering redraws the map, suppression ensures that certain voices remain silent within those boundaries. To restore balance, reforms must address both issues simultaneously, ensuring that districts are fairly drawn and that every eligible voter can cast a ballot without undue burden. The question is not just which party gerrymanders more, but how their suppression tactics deepen the inequities created by those maps.

Alexander Hamilton's Political Party: Federalist or Something Else?

You may want to see also

Role of technology in gerrymandering

Technology has revolutionized the practice of gerrymandering, transforming it from an art into a precise science. Advanced mapping software, such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS), allows political operatives to dissect voter data with unprecedented granularity. These tools enable the manipulation of district boundaries to favor specific political outcomes, often by diluting the voting power of opposition supporters. For instance, Republicans in North Carolina used sophisticated algorithms to pack Democratic voters into a few districts, ensuring Republican majorities in the remaining ones. This level of precision was unimaginable before the digital age, highlighting how technology amplifies the effectiveness of gerrymandering.

The role of technology in gerrymandering extends beyond mapping software to include big data analytics. Political parties now leverage voter databases, social media activity, and consumer behavior to predict voting patterns with remarkable accuracy. By combining these datasets, parties can identify which neighborhoods, streets, or even households are most likely to support their opponents. This hyper-targeted approach allows for the surgical carving of districts that maximize partisan advantage. Democrats in Illinois, for example, have used such data-driven strategies to consolidate Republican voters into fewer districts, securing Democratic dominance in the state legislature. The takeaway is clear: technology doesn’t just facilitate gerrymandering—it supercharges it.

While technology empowers gerrymandering, it also offers tools to combat it. Open-source mapping platforms and transparency initiatives have emerged to counterbalance partisan manipulation. Organizations like the Public Mapping Project provide accessible software for citizens to draw fairer district maps, democratizing a process once controlled by political elites. Additionally, courts increasingly rely on algorithmic simulations to evaluate the fairness of proposed maps. In 2019, a federal court struck down Michigan’s gerrymandered districts after experts used computer models to demonstrate their bias. This dual-edged nature of technology underscores its potential to both perpetuate and mitigate gerrymandering, depending on who wields it.

Despite these countermeasures, the arms race between gerrymandering technology and anti-gerrymandering tools continues. Political parties invest heavily in proprietary software and data analytics firms to stay ahead, creating an asymmetry in resources. Wealthier parties or those in power often have greater access to cutting-edge technology, giving them an unfair advantage. For instance, the Republican State Leadership Committee’s REDMAP program has been instrumental in securing GOP control of state legislatures through strategic redistricting. Until campaign finance and technology access are more equitably regulated, technology will remain a double-edged sword in the gerrymandering debate.

Can Citizens Legally Dismantle a Political Party? Exploring the Possibilities

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Both parties engage in gerrymandering when they have the power to do so, but in recent decades, Republicans have been more active and successful in redrawing district lines to their advantage, particularly after the 2010 census.

No, gerrymandering is practiced by both major political parties in the U.S., but the extent and impact vary depending on which party controls state legislatures during redistricting cycles.

While Democrats have engaged in gerrymandering, Republicans have been more aggressive and widespread in their efforts, particularly in states where they hold full control of the redistricting process.

In recent years, Republicans have benefited more from gerrymandering in congressional elections, as they have controlled more state legislatures during key redistricting periods, allowing them to draw maps that favor their candidates.