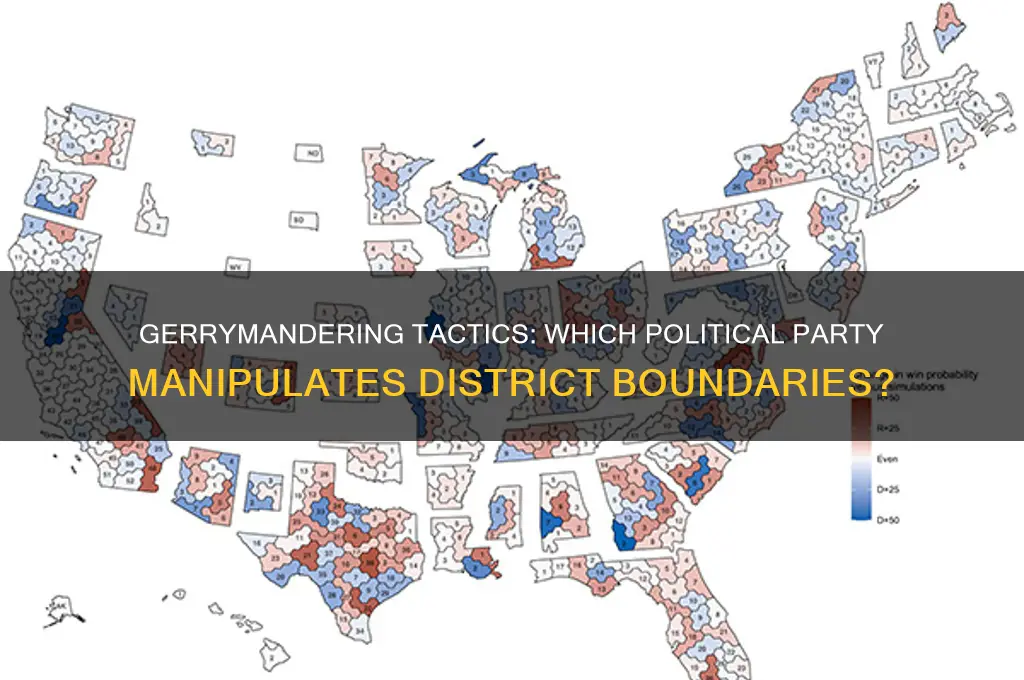

Gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating electoral district boundaries to favor one political party over another, has long been a contentious issue in American politics. While both major parties, Democrats and Republicans, have historically engaged in gerrymandering, the extent and impact of this practice vary significantly depending on which party holds power in state legislatures during the redistricting process. In recent years, Republicans have been particularly effective in leveraging gerrymandering to secure disproportionate representation in Congress and state legislatures, often through strategic redistricting after the 2010 and 2020 censuses. However, Democrats have also employed similar tactics in states where they control the redistricting process, such as Illinois and Maryland. The debate over which party gerrymanders more frequently or effectively often hinges on the specific state, the timing of redistricting, and the legal and political constraints in place. Ultimately, the practice remains a bipartisan issue, though its consequences are deeply felt across the political spectrum.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Party Most Associated | Republican Party (historically more recent and widespread) |

| Primary Method | Packing and cracking Democratic voters into districts |

| Key States Affected | North Carolina, Texas, Wisconsin, Ohio, Florida, Georgia |

| Legal Challenges | Numerous court cases (e.g., Rucho v. Common Cause, state-level rulings) |

| Impact on Elections | Disproportionate Republican representation in state legislatures and Congress |

| Recent Trends | Increased use of sophisticated data and software for precise redistricting |

| Public Perception | Widely criticized as undemocratic and partisan manipulation |

| Countermeasures | Democratic-led lawsuits, independent redistricting commissions in some states |

| Historical Context | Both parties have gerrymandered, but Republicans have dominated since 2010 |

| Federal Response | Limited due to Supreme Court rulings (e.g., 2019 decision deferring to states) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Historical Examples of Gerrymandering

Gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating electoral boundaries for political advantage, has a long and contentious history in the United States. One of the earliest and most infamous examples dates back to 1812 in Massachusetts, where Governor Elbridge Gerry signed a redistricting bill that created a district resembling a salamander. This bizarrely shaped district was designed to favor his Democratic-Republican Party, giving rise to the term "gerrymander." The Federalist-controlled newspaper *The Boston Gazette* coined the term, combining "Gerry" with "salamander," and the practice has since become a staple of American political strategy.

Fast forward to the post-Civil War era, and gerrymandering became a tool to suppress African American voting rights. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Southern states redrew districts to dilute the voting power of newly enfranchised Black citizens. For instance, in North Carolina, districts were crafted to pack Black voters into as few districts as possible, minimizing their influence in state and federal elections. This tactic, known as "packing and cracking," remains a common method of gerrymandering today, though its origins in racial disenfranchisement are often overlooked.

The 20th century saw both major political parties engaging in gerrymandering, often with significant consequences. In the 1960s, Democrats in Texas redrew districts to protect incumbent representatives, a move that sparked legal challenges and set the stage for future battles over redistricting. Conversely, in the 1990s, Republicans in Georgia were accused of gerrymandering to increase their representation in Congress. These examples illustrate how gerrymandering has been a bipartisan issue, with both parties leveraging the practice to secure political power.

One of the most striking modern examples occurred in Pennsylvania in 2011, where Republican lawmakers redrew congressional districts to favor their party. The resulting map was so extreme that it led to a landmark Supreme Court case, *League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania*. In 2018, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court struck down the map as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander, highlighting the ongoing legal battles surrounding this practice. This case underscores the enduring challenge of balancing political interests with fair representation.

While gerrymandering has historically been a tool for both parties, its impact on democracy remains a pressing concern. By distorting electoral maps, politicians undermine the principle of "one person, one vote," eroding public trust in the political process. Understanding these historical examples is crucial for addressing the issue today, as it reveals the long-standing nature of the problem and the need for systemic reforms to ensure fair and equitable elections.

Understanding UK Politics: Key Differences Among British Political Parties

You may want to see also

Impact on Election Outcomes

Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party, has a profound and measurable impact on election outcomes. By strategically clustering or dispersing voters, parties can secure more seats than their overall vote share would otherwise warrant. For instance, in the 2012 U.S. House elections, Democrats won 1.4 million more votes nationwide than Republicans but still secured 33 fewer seats due to Republican-drawn maps in key states like Pennsylvania and Michigan. This disparity illustrates how gerrymandering can distort democratic representation, turning elections into predetermined outcomes rather than genuine contests.

To understand the mechanics, consider a hypothetical state with 100 voters, 55 of whom favor Party A and 45 Party B. If districts are drawn fairly, Party A might win 5 or 6 out of 10 seats. However, through gerrymandering, Party A could pack Party B voters into a few districts, ensuring overwhelming victories there, while spreading their own voters across the remaining districts to secure narrow wins. The result? Party A wins 7 or 8 seats despite having only 55% of the vote. This tactic, known as "cracking and packing," highlights how gerrymandering can amplify a party’s power beyond its actual support base.

The impact isn’t just theoretical; it’s systemic. In North Carolina’s 2018 congressional elections, Republicans won 50.3% of the statewide vote but secured 77% of the seats due to gerrymandered maps. Similarly, in Maryland, Democrats have used gerrymandering to maintain a 7-1 advantage in the House delegation despite Republicans consistently winning around 40% of the statewide vote. These examples demonstrate how gerrymandering can create electoral fortresses, insulating incumbents and stifling competitive races. Over time, this undermines the principle of "one person, one vote" and erodes public trust in the electoral process.

Countering gerrymandering requires both legal and procedural reforms. Independent redistricting commissions, as used in states like California and Arizona, can remove partisan bias from the map-drawing process. Additionally, courts have increasingly struck down egregious gerrymanders, with the Supreme Court ruling in *Rucho v. Common Cause* (2019) that federal courts cannot intervene in partisan gerrymandering cases, leaving the issue to state legislatures and voters. However, state-level initiatives, such as ballot measures in Michigan and Colorado, have successfully transferred redistricting power to nonpartisan bodies, offering a blueprint for other states to follow.

Ultimately, the impact of gerrymandering on election outcomes is a stark reminder of the fragility of democratic institutions. While it may provide short-term gains for the party in power, it comes at the cost of fair representation and voter confidence. Addressing this issue requires vigilance, transparency, and a commitment to equitable electoral practices. Without such measures, gerrymandering will continue to skew election results, perpetuating a system where the map—not the voters—determines the winner.

The Rise of 1790 Political Parties: Key Factors and Catalysts

You may want to see also

Legal Challenges and Reforms

Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party over another, has long been a contentious issue in American politics. Both major parties have engaged in this tactic, but legal challenges and reforms are increasingly shaping the landscape. Here’s how the battle against gerrymandering is unfolding in the courts and legislatures.

One of the most significant legal developments came in the 2019 Supreme Court case *Rucho v. Common Cause*, where the Court ruled that federal courts cannot review claims of partisan gerrymandering, deeming it a non-justiciable political question. This decision shifted the focus to state courts and legislatures, where challenges have since proliferated. For instance, in 2022, the North Carolina Supreme Court struck down the state’s congressional and legislative maps as unconstitutional partisan gerrymanders, forcing the redrawing of districts. This case exemplifies how state-level litigation can serve as a critical check on partisan overreach, even when federal remedies are limited.

Reforms are also gaining traction through ballot initiatives and legislative action. In states like Michigan, Ohio, and Colorado, voters have approved independent redistricting commissions to draw electoral maps, removing the process from the hands of self-interested lawmakers. These commissions, often composed of bipartisan or nonpartisan members, aim to create fairer districts based on objective criteria such as population density and geographic continuity. For advocates, this approach reduces the potential for manipulation and fosters greater public trust in the electoral system. However, implementing such reforms requires careful design to ensure transparency and accountability.

Despite these advances, challenges remain. Partisan actors continue to exploit loopholes, such as using racial gerrymandering claims to mask partisan intent or manipulating voter registration data to skew district boundaries. Additionally, the lack of uniform federal standards leaves room for inconsistency across states. To address these issues, organizations like the Brennan Center for Justice advocate for clearer legal benchmarks and increased public participation in the redistricting process. Practical steps include educating voters about their rights, monitoring legislative hearings, and leveraging technology to analyze proposed maps for fairness.

In conclusion, while gerrymandering persists as a tool for political advantage, legal challenges and reforms are creating pathways to mitigate its impact. State courts, independent commissions, and grassroots efforts are proving instrumental in this fight. As the 2024 redistricting cycle approaches, the lessons from recent battles underscore the importance of vigilance, innovation, and collaboration in safeguarding democratic integrity.

The Harmful Impact of Political Censorship on Democracy and Freedom

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$59.99

Techniques Used in Gerrymandering

Gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating electoral district boundaries for political advantage, relies on a toolkit of sophisticated techniques. One of the most common methods is cracking, which dilutes the voting power of the opposing party by spreading their supporters thinly across multiple districts. For example, in North Carolina’s 2016 redistricting, Democratic voters were dispersed across several districts, ensuring Republican majorities in most. This technique effectively minimizes the impact of concentrated opposition, even if their overall numbers are significant.

Another key technique is packing, where voters from the opposing party are concentrated into a single district, creating a "wasted vote" scenario. By packing these voters into one district, the gerrymandering party ensures overwhelming victory in that district while securing narrow wins in surrounding areas. A notable example is Maryland’s 6th Congressional District, which was redrawn in 2011 to pack Republican voters, making it easier for Democrats to win other districts. This method maximizes the gerrymandering party’s seat count while minimizing the opposition’s representation.

Hijacking is a more subtle technique, where a district’s boundaries are redrawn to include a small but strategically important group of voters. This often involves targeting specific neighborhoods or communities known to lean toward the gerrymandering party. For instance, in Ohio’s 2012 redistricting, urban Democratic voters were carved out of certain districts and placed into heavily Republican ones, flipping the political balance in favor of the GOP. This precision targeting can shift the outcome of elections without drastically altering the overall map.

A less obvious but equally effective technique is kidnapping, where an incumbent legislator is drawn out of their own district, forcing them to run in unfamiliar territory or against a colleague. This disrupts the opposition’s organizational structure and reduces their chances of reelection. In Pennsylvania’s 2011 redistricting, Democratic incumbents were "kidnapped" into Republican-leaning districts, contributing to GOP gains in the state. This tactic not only weakens the opposition but also creates internal divisions within their party.

Finally, tacking involves extending district boundaries to include favorable voters from neighboring areas, often in irregular shapes that defy geographic logic. The infamous Illinois 4th District, dubbed "the earmuffs" for its bizarre shape, is a prime example. By tacking on distant but politically aligned communities, gerrymanders can secure a majority without relying on local demographics. This method often results in districts that bear no resemblance to natural communities, highlighting the artificial nature of gerrymandering.

Understanding these techniques is crucial for identifying and combating gerrymandering. While both major political parties in the U.S. have engaged in these practices, the frequency and scale often depend on which party controls the redistricting process. By recognizing the methods used, voters and advocates can push for reforms like independent redistricting commissions to ensure fairer electoral maps.

Mussolini's Political Beliefs: Fascism, Nationalism, and Totalitarian Vision Explained

You may want to see also

Partisan vs. Nonpartisan Redistricting Efforts

Gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating electoral district boundaries for political advantage, has long been a contentious issue in American politics. While both major parties have engaged in this tactic, the question of which party gerrymanders more often or more effectively is complex. Partisan redistricting efforts, driven by state legislatures controlled by either Democrats or Republicans, often prioritize securing or expanding political power. In contrast, nonpartisan efforts aim to create fair and representative districts, typically through independent commissions or algorithmic approaches. Understanding the differences between these approaches is crucial for addressing the broader implications of gerrymandering on democracy.

Partisan redistricting efforts are inherently self-serving, as they allow the party in power to draw district lines that favor their candidates. For example, in states like North Carolina and Ohio, Republican-controlled legislatures have been accused of creating maps that dilute Democratic votes, ensuring GOP dominance in congressional delegations. Similarly, in states like Maryland, Democratic-led redistricting has been criticized for packing Republican voters into fewer districts, minimizing their representation. These tactics often result in uncompetitive elections, reduced voter turnout, and a distorted reflection of the electorate’s will. The Supreme Court’s 2019 ruling in *Rucho v. Common Cause* further complicated matters by declaring federal courts powerless to address partisan gerrymandering, leaving states to self-regulate.

Nonpartisan redistricting efforts, on the other hand, seek to remove political bias from the process. States like California and Arizona have established independent commissions tasked with drawing district lines based on criteria such as population equality, contiguity, and respect for communities of interest. These commissions often include a mix of Democrats, Republicans, and unaffiliated voters to ensure balance. Additionally, technological advancements have introduced algorithmic redistricting, which uses computer models to create maps free from political influence. While not perfect, these methods have shown promise in reducing gerrymandering and fostering more competitive elections. For instance, California’s nonpartisan commission has been credited with creating districts that better reflect the state’s diverse population.

Implementing nonpartisan redistricting requires careful consideration of potential pitfalls. Independent commissions, though effective, can face challenges such as partisan deadlock or legal disputes over their authority. Algorithmic approaches, while objective, may overlook nuanced community interests or demographic considerations. To maximize their effectiveness, states adopting nonpartisan methods should establish clear, transparent criteria for map-drawing, ensure public input, and provide adequate funding for commission operations. Voters can also play a role by supporting ballot initiatives that mandate nonpartisan redistricting, as seen in states like Michigan and Colorado.

Ultimately, the choice between partisan and nonpartisan redistricting efforts reflects broader values about the role of politics in democracy. Partisan gerrymandering prioritizes party power, often at the expense of fair representation. Nonpartisan methods, while not a panacea, offer a pathway toward more equitable and responsive electoral systems. As debates over redistricting continue, the lessons from both approaches underscore the importance of balancing political interests with the principles of democratic governance. By prioritizing fairness over partisanship, states can help restore public trust in the electoral process and ensure that every vote counts.

Unveiling James Polite: A Deep Dive into His Life and Legacy

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Both major political parties in the United States, the Democratic Party and the Republican Party, have historically engaged in gerrymandering when they have controlled the redistricting process. The party in power often redraws district lines to favor their candidates.

Republicans have been more frequently accused of gerrymandering in recent decades, particularly after the 2010 census, when they controlled more state legislatures. However, Democrats have also engaged in gerrymandering in states where they hold power.

While Democrats have gerrymandered in states like Maryland and Illinois, Republicans have been more widespread in their efforts, especially in states like North Carolina, Ohio, and Texas. The extent of gerrymandering depends on which party controls the redistricting process.

No, gerrymandering is not exclusive to one party. Both Democrats and Republicans have used the practice to gain political advantage. The key factor is which party holds the majority in state legislatures during the redistricting process.