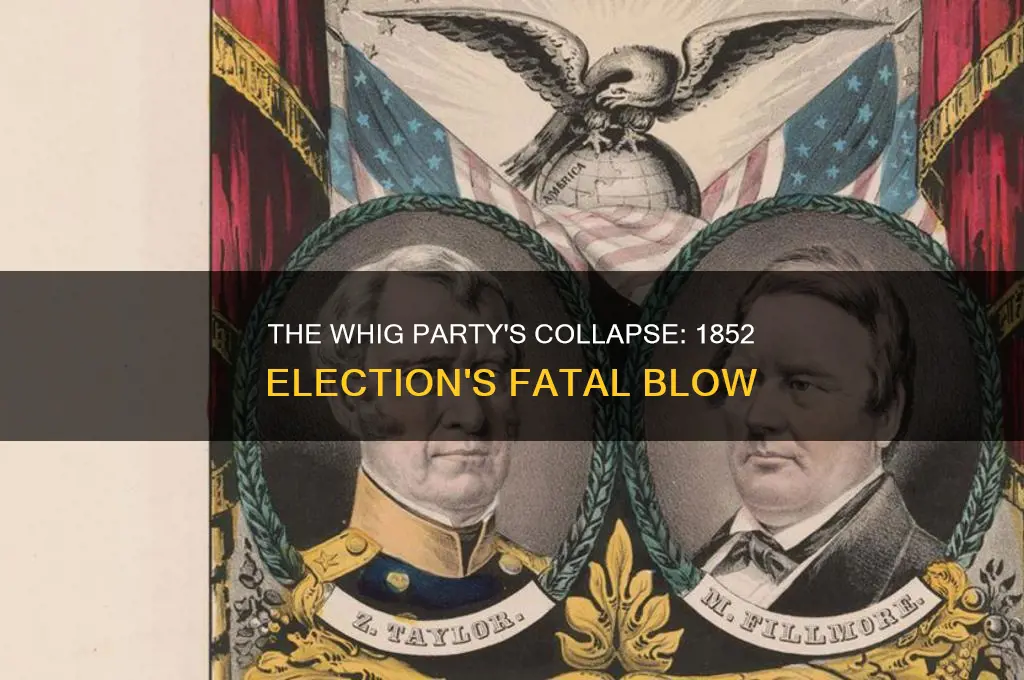

The 1852 U.S. presidential election marked a significant turning point in American political history, as it effectively signaled the demise of the Whig Party, one of the two major political parties at the time. Despite nominating General Winfield Scott, a highly respected military figure, the Whigs were unable to overcome deep internal divisions over slavery and other contentious issues. The party's inability to present a unified front, coupled with the Democratic Party's successful nomination of Franklin Pierce, led to a decisive Democratic victory. The Whigs' defeat in 1852 exposed their fragility and inability to adapt to the changing political landscape, ultimately leading to the party's dissolution and the rise of the Republican Party as the primary opposition to the Democrats.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Party Name | Whig Party |

| Year Ended | 1856 (effectively dissolved after the 1852 election) |

| Reason for Dissolution | Internal divisions over slavery and inability to unite on a single platform |

| Key Figures | Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, John Quincy Adams |

| Ideology | National conservatism, modernization, protective tariffs, internal improvements |

| Major Achievements | Established the Second Bank of the United States, promoted infrastructure projects |

| Last Presidential Candidate | Winfield Scott (1852) |

| Successor Parties | Republican Party, American Party (Know-Nothings), Constitutional Union Party |

| Historical Significance | Played a major role in U.S. politics during the Second Party System (1828–1854) |

Explore related products

$48.89 $55

What You'll Learn

- Whig Party's Decline: Internal divisions over slavery weakened the Whigs, leading to their downfall

- Election Results: Franklin Pierce's victory marked the Whigs' inability to win the presidency

- Rise of Republicans: The Republican Party emerged, absorbing anti-slavery Whigs and ending Whig dominance

- Sectional Tensions: Slavery debates fractured the Whigs, making them irrelevant in national politics

- Legacy of Whigs: Whig policies influenced later parties, but their structure collapsed post-1852

Whig Party's Decline: Internal divisions over slavery weakened the Whigs, leading to their downfall

The 1852 election marked a turning point in American political history, as it signaled the beginning of the end for the Whig Party. Founded in the 1830s, the Whigs had been a major force in American politics, advocating for modernization, economic growth, and internal improvements. However, by the early 1850s, the party was plagued by internal divisions, particularly over the issue of slavery. These fractures would ultimately prove fatal, as the Whigs failed to nominate a compelling presidential candidate in 1852, leading to a landslide victory for Democrat Franklin Pierce. This defeat exposed the party's inability to unite around a common platform, setting the stage for its eventual dissolution.

To understand the Whigs' decline, consider the party's structural weaknesses. Unlike the Democrats, who had a clear regional base in the South, the Whigs were a coalition of diverse interests, including Northern industrialists, Southern planters, and Western farmers. This diversity, while initially a strength, became a liability as the slavery debate intensified. Northern Whigs increasingly opposed the expansion of slavery, while their Southern counterparts defended it as essential to their way of life. The Compromise of 1850, which temporarily eased tensions, only papered over these divisions. By 1852, the party's inability to reconcile these opposing views left it vulnerable to collapse.

A persuasive argument can be made that the Whigs' failure to address slavery head-on was their fatal flaw. While the party focused on economic issues like tariffs and infrastructure, the moral and political implications of slavery could no longer be ignored. The emergence of the Republican Party in the mid-1850s, which explicitly opposed the expansion of slavery, further marginalized the Whigs. Northern voters, disillusioned with their party's equivocation, began to defect to the Republicans, while Southern Whigs either joined the Democrats or formed short-lived splinter groups. This exodus of support left the Whigs without a viable constituency, rendering them politically irrelevant.

Comparatively, the Democrats managed to survive the tumultuous 1850s by adopting a strategy of sectional balance, even if it meant compromising their principles. The Whigs, however, lacked such flexibility. Their internal divisions were not merely ideological but deeply personal, with prominent leaders like Henry Clay and Daniel Webster unable to bridge the gap between North and South. The party's final presidential candidate, Winfield Scott, a war hero with limited political experience, was unable to inspire confidence or unity. His overwhelming defeat in 1852 was less a reflection of his abilities and more a symptom of the Whigs' terminal decline.

In practical terms, the Whigs' downfall offers a cautionary tale for modern political parties. Internal cohesion is as critical as external appeal. Parties must navigate contentious issues with clarity and unity, or risk alienating their base. For historians and political analysts, the Whigs' collapse underscores the importance of studying not just a party's policies, but its internal dynamics. By examining how slavery fractured the Whigs, we gain insight into the fragility of political coalitions and the enduring impact of moral dilemmas on party survival. The Whigs' story is not just a footnote in history but a lesson in the consequences of division.

Maximilien Robespierre's Political Rise: A Revolutionary Journey Begins

You may want to see also

1852 Election Results: Franklin Pierce's victory marked the Whigs' inability to win the presidency

The 1852 presidential election stands as a pivotal moment in American political history, signaling the decline of the Whig Party and the rise of the Democratic Party under Franklin Pierce. Pierce’s decisive victory, securing 27 of the 31 states and 254 electoral votes, exposed the Whigs’ fatal inability to adapt to the nation’s shifting political landscape. While Whig candidate Winfield Scott, a respected military figure, seemed a strong contender on paper, his campaign was marred by internal party divisions and a lack of clear policy direction. This election was not merely a contest between candidates but a referendum on the Whigs’ viability as a national party.

To understand the Whigs’ downfall, consider their structural weaknesses. The party, founded in opposition to Andrew Jackson’s Democratic Party, had long relied on a coalition of economic modernizers, anti-Jacksonians, and regional interests. By 1852, however, the issue of slavery had fractured this coalition. While Northern Whigs leaned toward abolitionism, their Southern counterparts resisted any threat to the institution. This ideological split rendered the party incapable of presenting a unified platform, leaving Scott to navigate an impossible divide. Pierce, in contrast, benefited from the Democrats’ disciplined focus on national unity and the preservation of the Union, even if it meant sidestepping the slavery question.

A comparative analysis of the candidates’ strategies further highlights the Whigs’ failure. Pierce’s campaign emphasized his military service in the Mexican-American War and his appeal as a “northern man with southern principles,” a stance that reassured Southern voters. Scott, meanwhile, alienated Southern Whigs by failing to endorse the Compromise of 1850, a critical piece of legislation that temporarily defused sectional tensions. His association with the nativist “Know-Nothing” movement also alienated immigrant voters, a growing demographic. These missteps underscored the Whigs’ inability to craft a message that resonated across regions or demographics.

The takeaway from the 1852 election is clear: the Whigs’ collapse was not merely a consequence of Pierce’s victory but a symptom of their own ideological incoherence and organizational dysfunction. The party’s inability to win the presidency was the final blow, as it had long defined its legitimacy through executive power. By 1856, the Whigs had dissolved, replaced by the emerging Republican Party, which capitalized on the Whigs’ failure by offering a clear stance against the expansion of slavery. Pierce’s triumph, therefore, was not just a personal victory but a harbinger of the two-party realignment that would define the Civil War era.

Practically speaking, this election offers a cautionary tale for modern political parties: adaptability and unity are essential for survival. Parties must address the dominant issues of their time with clarity and coherence, or risk obsolescence. The Whigs’ inability to do so in 1852 serves as a timeless reminder of the consequences of internal division and ideological ambiguity in the face of national crises.

John Adams' Political Party Affiliation: A Historical Overview

You may want to see also

Rise of Republicans: The Republican Party emerged, absorbing anti-slavery Whigs and ending Whig dominance

The 1852 election marked a turning point in American political history, as the Whig Party, once a dominant force, began its irreversible decline. This collapse wasn’t merely a loss at the polls; it was the culmination of internal fractures over slavery and the rise of a new political force: the Republican Party. Founded in 1854, the Republicans emerged as a coalition of anti-slavery Whigs, Free Soilers, and disaffected Democrats, united by their opposition to the expansion of slavery into western territories. This realignment reshaped the political landscape, leaving the Whigs, unable to reconcile their pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions, to dissolve by the late 1850s.

To understand this shift, consider the Whigs’ fatal inability to address the slavery question. While the party had historically focused on economic modernization and internal improvements, the issue of slavery increasingly polarized the nation. Anti-slavery Whigs, disillusioned by their party’s unwillingness to take a firm stand, found a new home in the Republican Party. The 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, which effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise and allowed slavery in new territories, accelerated this exodus. The Republicans capitalized on this outrage, framing themselves as the party of freedom and progress, while the Whigs were left stranded, their ideological ambiguity proving fatal.

The Republican Party’s rise wasn’t just about absorbing anti-slavery Whigs; it was a strategic consolidation of disparate anti-slavery forces. By uniting former Whigs, Free Soilers, and anti-slavery Democrats, the Republicans created a powerful coalition that could challenge the Democratic Party’s dominance. Their platform, centered on halting the spread of slavery, resonated with Northern voters, who increasingly viewed slavery as a moral and economic threat. This clarity of purpose contrasted sharply with the Whigs’ equivocation, making the Republicans the natural successor to the anti-slavery cause.

Practically, the Republicans’ success hinged on their ability to mobilize grassroots support. They organized rallies, published newspapers, and leveraged local networks to spread their message. For instance, in states like Ohio and Pennsylvania, former Whig leaders like Salmon P. Chase and Thaddeus Stevens played pivotal roles in building the Republican Party’s infrastructure. Their efforts paid off in the 1856 election, when the Republicans secured a strong showing despite losing the presidency. By 1860, they had become a national force, electing Abraham Lincoln and setting the stage for the Civil War.

In retrospect, the Whigs’ demise was less a sudden collapse than a slow unraveling, hastened by their failure to adapt to the moral and political imperatives of their time. The Republican Party, by contrast, seized the moment, offering a clear alternative to a divided nation. Their rise wasn’t just the end of Whig dominance; it was the beginning of a new era in American politics, one defined by the struggle over slavery and the eventual triumph of the Union. For historians and political observers, this period offers a stark reminder of how parties rise and fall not just on policy, but on their ability to align with the moral currents of their age.

Understanding the Core Principles of the Conservative Party's Political Ideology

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Sectional Tensions: Slavery debates fractured the Whigs, making them irrelevant in national politics

The 1852 election marked the final nail in the coffin for the Whig Party, a once-dominant force in American politics. At the heart of their demise lay the irreconcilable divide over slavery, an issue that splintered the party into factions incapable of unity. The Whigs, initially a coalition of diverse interests, found themselves paralyzed by the growing sectional tensions between the North and South. While Northern Whigs increasingly aligned with anti-slavery sentiments, their Southern counterparts clung to the institution as vital to their economic and social order. This ideological rift rendered the party unable to present a cohesive platform, leaving them irrelevant in a nation hurtling toward crisis.

Consider the Whig Party’s inability to nominate a presidential candidate in 1852 without alienating a significant portion of its base. Their eventual nominee, General Winfield Scott, a war hero with moderate views on slavery, failed to inspire enthusiasm. Southern Whigs viewed him as too sympathetic to Northern anti-slavery interests, while Northern Whigs saw him as insufficiently committed to their cause. This internal discord contrasted sharply with the Democratic Party’s ability to unite behind Franklin Pierce, a candidate who appealed to both Northern and Southern Democrats by avoiding a clear stance on slavery. The Whigs’ failure to navigate this issue exposed their fatal weakness: they could neither embrace abolition nor defend slavery without fracturing further.

The Compromise of 1850, intended to ease sectional tensions, instead deepened the Whigs’ divisions. Northern Whigs, like Senator William Seward, opposed the Fugitive Slave Act, which required Northerners to assist in the return of escaped slaves. Southern Whigs, however, supported the compromise as a means of preserving the Union and their way of life. This legislative battle laid bare the party’s inability to reconcile its Northern and Southern wings. By 1852, the Whigs had become a party of contradictions, unable to articulate a coherent vision for the nation’s future. Their inability to adapt to the shifting political landscape made them obsolete in the eyes of voters.

The rise of the Republican Party in the North further accelerated the Whigs’ decline. Formed in 1854, the Republicans explicitly opposed the expansion of slavery, attracting disaffected Northern Whigs and anti-slavery Democrats. The Whigs, by contrast, remained trapped in their internal struggles, unable to compete with the Republicans’ clear and compelling message. The 1852 election was not just a defeat for the Whigs; it was a referendum on their failure to address the defining issue of the era. As slavery debates intensified, the Whigs’ inability to take a decisive stand rendered them irrelevant in national politics, paving the way for their eventual dissolution.

In practical terms, the Whigs’ collapse offers a cautionary tale for modern political parties. A party’s survival depends on its ability to adapt to changing societal values and address divisive issues head-on. The Whigs’ failure to bridge the gap between their Northern and Southern factions highlights the dangers of internal fragmentation. For contemporary parties, this means prioritizing unity over ideological purity and recognizing that compromise, when rooted in shared principles, is essential for long-term viability. The Whigs’ demise serves as a reminder that ignoring the fault lines within a party can lead to its extinction, even in the face of external success.

Exploring the Core Theories Behind Political Parties and Their Functions

You may want to see also

Legacy of Whigs: Whig policies influenced later parties, but their structure collapsed post-1852

The Whig Party, a dominant force in American politics during the 1830s and 1840s, met its demise after the 1852 election, but its influence persisted long after its structural collapse. This party, known for its emphasis on economic modernization, internal improvements, and a strong federal government, left a lasting imprint on the nation’s political landscape. While the Whigs disbanded due to irreconcilable internal divisions over slavery, their policies and ideological frameworks became the bedrock for future political movements, particularly the Republican Party.

Consider the Whigs’ economic agenda, which championed infrastructure development, such as roads, canals, and railroads, to foster national growth. These policies were not merely theoretical; they were practical blueprints for progress. For instance, the Whigs’ support for the American System, devised by Henry Clay, included protective tariffs, a national bank, and federal funding for internal improvements. These ideas did not vanish with the party’s dissolution. Instead, they were adopted and adapted by the Republicans, who emerged as a major force in the 1850s. The Republican Party’s early platform, which prioritized economic development and national unity, owed much to Whig precedents. This continuity demonstrates how the Whigs’ policy legacy outlived their organizational structure.

However, the Whigs’ collapse also serves as a cautionary tale about the fragility of political coalitions. The party’s inability to resolve internal conflicts over slavery—particularly the question of its expansion into new territories—led to its fragmentation. Northern Whigs increasingly aligned with anti-slavery sentiments, while Southern Whigs clung to pro-slavery positions. This ideological rift was exacerbated by the Compromise of 1850, which temporarily delayed but did not resolve the issue. By 1852, the party’s presidential candidate, Winfield Scott, suffered a crushing defeat, signaling the end of the Whigs as a viable national party. This structural failure highlights the importance of cohesive leadership and shared principles in sustaining a political organization.

Despite their demise, the Whigs’ influence is evident in the evolution of American political thought. Their emphasis on federal authority and economic intervention laid the groundwork for later progressive policies. For example, the Republican Party’s support for the Homestead Act of 1862 and the transcontinental railroad mirrored Whig priorities. Similarly, the Whigs’ commitment to public education and moral reform resonated in subsequent reform movements. Even today, debates over the role of government in economic development often echo Whig arguments. This enduring impact underscores the Whigs’ role as architects of modern American political ideology.

In practical terms, understanding the Whigs’ legacy offers valuable lessons for contemporary politics. Parties must balance ideological consistency with adaptability to changing circumstances. The Whigs’ failure to address the slavery issue serves as a reminder that unresolved internal divisions can be fatal. Conversely, their policy innovations demonstrate the power of forward-thinking agendas. For political strategists, studying the Whigs provides a roadmap for crafting platforms that resonate across generations. By learning from their successes and failures, modern parties can avoid the pitfalls that led to the Whigs’ collapse while building on their enduring contributions.

Hydro Flask's Political Party: Unveiling the Brand's Allegiance and Values

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Whig Party effectively collapsed after the 1852 election due to internal divisions over slavery and the rise of the Republican Party.

The Whig Party dissolved due to its inability to unite on the issue of slavery, with Northern and Southern factions increasingly at odds, and the emergence of the Republican Party as a viable alternative.

The last Whig Party candidate to run in the 1852 presidential election was General Winfield Scott, who lost decisively to Democratic candidate Franklin Pierce.

![By Michael F. Holt - The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics (1999-07-02) [Hardcover]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51TQpKNRjoL._AC_UY218_.jpg)

![General Election, 1852. Poll Book of the North Lincolnshire Election, with a History of the Election [&C.]. Ed. by T. Fricker 1852 Leather Bound](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)