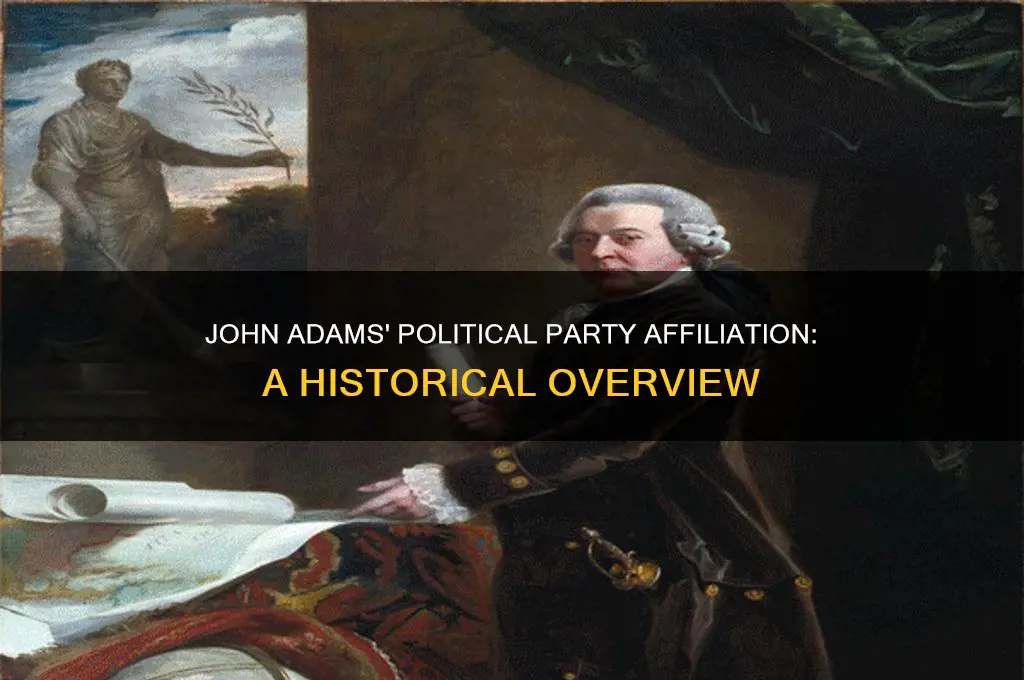

John Adams, the second President of the United States, was indeed associated with a political party, though the party system was still in its early stages during his time. Adams was a prominent member of the Federalist Party, which he co-founded alongside figures like Alexander Hamilton. The Federalists advocated for a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain, contrasting with the Democratic-Republican Party led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Adams’s presidency (1797–1801) was marked by his alignment with Federalist principles, though internal divisions within the party and his disagreements with Hamilton eventually weakened his political standing. His association with the Federalists played a significant role in shaping early American politics and the emergence of the two-party system.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Party Affiliation | John Adams was associated with the Federalist Party. |

| Role in Party Formation | He was one of the founding figures of the Federalist Party. |

| Presidency | Served as the 2nd President of the United States (1797–1801) as a Federalist. |

| Political Ideology | Supported strong central government, industrialization, and commerce. |

| Key Policies | Promoted the Alien and Sedition Acts during his presidency. |

| Opposition | Opposed the Democratic-Republican Party led by Thomas Jefferson. |

| Post-Presidency | Remained a vocal Federalist until the party declined in the early 1800s. |

| Legacy | Considered a key figure in early American political party development. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Adams and the Federalist Party

John Adams, the second President of the United States, is often associated with the Federalist Party, though his relationship with the party was complex and evolved over time. Initially, Adams was not formally aligned with any political party, as the American political landscape was still taking shape during his early career. However, his policies and beliefs aligned closely with Federalist principles, particularly during his presidency from 1797 to 1801. The Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, advocated for a strong central government, a national bank, and close ties with Britain, all of which resonated with Adams’ vision for the young nation.

Adams’ association with the Federalists became more pronounced during his presidency, as he faced the challenge of navigating the Quasi-War with France and domestic political divisions. His signing of the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798, which restricted civil liberties and targeted opposition, was a hallmark of Federalist policy aimed at suppressing dissent. While these measures were intended to protect national security, they alienated many Americans and contributed to the rise of the Democratic-Republican Party led by Thomas Jefferson. Adams’ reliance on Federalist ideals during this period cemented his public perception as a Federalist president, despite his earlier reluctance to formally join any party.

A critical analysis of Adams’ relationship with the Federalists reveals both strategic alignment and personal reservations. Adams admired Hamilton’s economic policies but often clashed with him over foreign policy and the extent of federal power. Unlike the more dogmatic Federalists, Adams was wary of entangling the U.S. in European conflicts, as evidenced by his decision to pursue peace with France rather than war. This pragmatism sometimes placed him at odds with the party’s hardliners, suggesting that his association with the Federalists was more circumstantial than ideological.

To understand Adams’ role within the Federalist Party, consider the following practical takeaway: his presidency marked a transitional phase in American politics, where party affiliations were still fluid. Adams’ alignment with Federalist policies was driven by the exigencies of his time, not a rigid commitment to party doctrine. For historians or students studying this era, examining Adams’ actions through the lens of both Federalist ideology and his personal convictions provides a richer understanding of early American political dynamics.

In conclusion, while John Adams is often linked to the Federalist Party, his relationship with it was nuanced. His presidency reflected Federalist priorities, but his independent streak and pragmatic approach distinguished him from the party’s more doctrinaire members. This unique position highlights the complexities of early American politics and underscores Adams’ role as a bridge between the founding era and the emerging two-party system.

Munich Massacre's Political Aftermath: Birth of a New Party?

You may want to see also

Founding of the Federalist Party

John Adams, the second President of the United States, is often associated with the Federalist Party, but his relationship with the party was complex and evolved over time. While Adams was not a founding member of the Federalist Party, his presidency (1797–1801) coincided with the party’s rise to prominence, and his policies aligned closely with Federalist principles. The Federalist Party, formally organized in the early 1790s, emerged as a response to the political divisions surrounding the ratification of the U.S. Constitution and the formation of the new federal government. Its founding was driven by figures like Alexander Hamilton, who championed a strong central government, a national bank, and close ties with Britain—policies that Adams largely supported during his tenure.

The Federalist Party’s origins can be traced to the debates over the Constitution, where Federalists (initially known as "Federalists" in a broader sense) advocated for its ratification against Anti-Federalist opposition. The party formalized its structure during George Washington’s presidency, particularly after the emergence of the Democratic-Republican Party led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Adams, though not a formal member, was sympathetic to Federalist ideals, such as the need for a robust federal government to ensure stability and economic growth. His appointment of Federalist allies to key positions and his support for measures like the Alien and Sedition Acts further aligned him with the party, even if he never officially joined its ranks.

A critical aspect of the Federalist Party’s founding was its emphasis on economic nationalism, a vision championed by Hamilton and echoed in Adams’s policies. The party’s platform included the establishment of a national bank, tariffs to protect American industries, and a strong military to defend national interests. Adams’s administration continued these initiatives, such as expanding the Navy to combat French aggression during the Quasi-War. However, his independence and occasional disagreements with Federalist leaders, particularly over foreign policy, highlight the nuanced nature of his association with the party. For instance, Adams’s decision to pursue peace with France in 1799, rather than escalate the conflict, alienated some hardline Federalists.

The founding of the Federalist Party also reflected the growing partisan divide in early American politics. While Adams was not a party founder, his presidency became a focal point for Federalist ideals, making him a de facto leader of the party during his term. This alignment, however, came at a cost: Adams’s association with the Federalists contributed to his defeat in the 1800 election, as the Democratic-Republicans capitalized on public discontent with Federalist policies, such as the Alien and Sedition Acts. Despite this, the Federalist Party’s legacy, shaped in part by Adams’s presidency, remains a defining chapter in the development of American political parties.

In practical terms, understanding Adams’s relationship with the Federalist Party offers insight into the early dynamics of American politics. It underscores how presidents, even in the absence of formal party membership, can become central figures in partisan movements. For historians and political analysts, this period serves as a case study in the interplay between personal leadership and party ideology. For educators, it provides a rich example of how political parties evolve in response to national challenges and ideological debates. By examining Adams’s role, we gain a clearer picture of the Federalist Party’s founding and its impact on the nation’s political landscape.

Will Ritter's Political Advertising Strategies: Impact and Future Trends

You may want to see also

Adams' Role in Party Politics

John Adams, the second President of the United States, played a pivotal role in the early development of American party politics, though his relationship with political parties was complex and often fraught with tension. Initially, Adams was not formally associated with any political party, as the party system was still in its infancy during his presidency (1797–1801). However, his policies and actions aligned him with the Federalist Party, which he had helped shape through his earlier political career. The Federalists, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, advocated for a strong central government, a national bank, and close ties with Britain. Adams’ support for these principles, particularly his signing of the controversial Alien and Sedition Acts, cemented his association with the Federalist Party, even if he never formally joined it.

Adams’ role in party politics was marked by his struggle to balance his own principles with the demands of partisan loyalty. Unlike his successor, Thomas Jefferson, who was a founding figure of the Democratic-Republican Party, Adams was more of an independent thinker within the Federalist framework. This independence often put him at odds with other Federalists, particularly Hamilton, who criticized Adams for not being partisan enough. For instance, Adams’ decision to pursue peace with France during the Quasi-War, rather than escalate into full-scale conflict, alienated many hardline Federalists who favored a more aggressive stance. This tension highlights Adams’ reluctance to fully embrace the emerging two-party system, which was becoming increasingly polarized during his presidency.

One of the most significant takeaways from Adams’ role in party politics is his cautionary tale about the dangers of partisanship. His presidency was marred by bitter political divisions, both within his own party and between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. Adams’ failure to secure reelection in 1800, losing to Jefferson, was partly due to these divisions and the lack of unified support from Federalists. His experience underscores the challenges of governing in a partisan environment, particularly when one’s own party is fractured. Adams’ legacy in this regard serves as a reminder of the importance of principled leadership over blind party loyalty, a lesson that remains relevant in modern political discourse.

To understand Adams’ role in party politics, it’s instructive to compare him with his contemporaries. While Jefferson and Hamilton were staunch partisans, Adams occupied a middle ground, often prioritizing national unity over party interests. For example, his appointment of John Marshall as Chief Justice, a move that strengthened the federal judiciary, was a decision made with the long-term stability of the nation in mind, rather than short-term political gain. This approach, though admirable, ultimately left him isolated within his own party. Practical advice for modern politicians might include studying Adams’ emphasis on compromise and national interest, even if it means risking party disapproval.

In conclusion, John Adams’ role in party politics was characterized by his uneasy relationship with the Federalist Party and his resistance to the extremes of partisanship. His presidency offers valuable insights into the challenges of governing in a divided political landscape. By examining Adams’ actions and their consequences, we can glean lessons about the importance of balancing party loyalty with broader national goals. His legacy serves as a guide for navigating the complexities of party politics, emphasizing the need for principled leadership in an increasingly polarized world.

Are Democrats and Republicans Truly Different? Examining Political Party Similarities

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Opposition to Jefferson's Republicans

John Adams, the second President of the United States, was indeed associated with a political party—the Federalist Party. This affiliation positioned him in direct opposition to Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party, a rivalry that defined early American politics. The Federalists, led by figures like Adams and Alexander Hamilton, advocated for a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain. In contrast, Jefferson’s Republicans championed states’ rights, agrarianism, and alignment with France. This ideological divide created a sharp opposition that shaped Adams’ presidency and the political landscape of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

One of the most significant points of contention between Adams’ Federalists and Jefferson’s Republicans was the role of government. Federalists believed in a robust federal authority to ensure stability and economic growth, while Republicans feared this would lead to tyranny and undermine individual liberties. This clash was evident in the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts during Adams’ presidency, which Republicans viewed as an overreach of power and a threat to free speech. The Acts, designed to suppress dissent and strengthen federal control, became a rallying cry for Jefferson’s party, who framed them as an attack on democratic principles.

Opposition to Jefferson’s Republicans also manifested in foreign policy. Adams, though initially neutral, leaned toward Britain due to economic ties and shared strategic interests. Jefferson, however, favored France, seeing it as a natural ally in the fight against monarchy. This divide intensified during the Quasi-War with France, where Adams sought a diplomatic resolution, a move Republicans criticized as weak and pro-British. The Federalists’ emphasis on naval expansion and military preparedness further alienated Republicans, who saw it as unnecessary and costly.

Practical implications of this opposition were felt in everyday governance. For instance, the Federalist-dominated Congress often clashed with Jeffersonian appointees, slowing legislative progress. Voters, too, were polarized, with elections becoming bitter contests between the two parties. A key takeaway is that this opposition was not merely ideological but had tangible consequences for policy, diplomacy, and public sentiment. Understanding this dynamic provides insight into the roots of America’s two-party system and the enduring tensions between central authority and states’ rights.

To navigate this historical opposition today, consider studying primary sources like Adams’ and Jefferson’s writings to grasp their perspectives. Analyze how their disagreements influenced landmark policies, such as the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, which challenged Federalist authority. By examining these specifics, one can appreciate how early political rivalries laid the groundwork for modern American politics. This historical lens also underscores the importance of balanced governance, a lesson as relevant now as it was then.

Understanding Ranked Choice Voting: A Comprehensive Guide to RCV in Politics

You may want to see also

Legacy in Early U.S. Parties

John Adams, the second President of the United States, played a pivotal role in the early formation of American political parties, though his direct association with a specific party was nuanced. Initially, Adams aligned with the Federalist Party, which he co-founded alongside figures like Alexander Hamilton. The Federalists advocated for a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain, principles that resonated with Adams’ vision for the young nation. However, his presidency (1797–1801) marked a shift in his political standing. While he remained ideologically aligned with Federalist ideals, his actions, such as signing the controversial Alien and Sedition Acts, alienated both moderates and emerging Democratic-Republicans led by Thomas Jefferson.

Adams’ legacy in early U.S. parties is often analyzed through the lens of his inability to unite the Federalists or effectively counter the rising influence of Jefferson’s faction. Unlike Jefferson, who masterfully built a coalition of agrarian interests and states’ rights advocates, Adams struggled to maintain party cohesion. His vice president, Thomas Jefferson, was a political rival from the opposing Democratic-Republican Party, a structural flaw that underscored the fragility of early party politics. This dynamic highlights Adams’ role as a transitional figure, bridging the era of loose political factions and the emergence of disciplined parties.

A comparative analysis reveals Adams’ limitations as a party leader. While Hamilton’s strategic brilliance and Jefferson’s charisma galvanized their respective bases, Adams’ leadership style was more pragmatic than inspirational. His focus on constitutional governance and foreign policy, such as avoiding war with France through the Convention of 1800, failed to resonate with the partisan fervor of the time. This pragmatic approach, though statesmanlike, left him politically isolated, contributing to his defeat in the 1800 election.

Despite these challenges, Adams’ legacy in early U.S. parties is not one of failure but of foundational contribution. His presidency and political career underscored the importance of party discipline and ideological clarity in a fledgling democracy. The Federalists’ decline after 1800 can be partly attributed to their inability to adapt to changing political landscapes, a lesson Adams implicitly imparted. His correspondence with Jefferson in later years, which became a symbol of reconciliation, also reflects his belief in the necessity of political dialogue over partisan rigidity.

In practical terms, Adams’ experience offers a cautionary tale for modern political leaders. His inability to balance ideological purity with pragmatic governance serves as a reminder of the delicate equilibrium required in party politics. For historians and political analysts, studying Adams’ tenure provides insight into the evolution of American political parties, emphasizing the role of leadership, ideology, and adaptability in shaping their trajectories. His legacy, while complex, remains integral to understanding the roots of U.S. partisan politics.

Unveiling Political Realities: What Lies Beneath the Surface in Politics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, John Adams was associated with the Federalist Party, which he co-founded and led during his presidency.

John Adams was a key figure in the Federalist Party, serving as its leader and the second President of the United States under its banner.

No, the Federalist Party was the first formal political party in the United States, and John Adams was one of its founding members.

John Adams’s Federalist Party favored a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain, while Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party advocated for states’ rights, agrarianism, and closer ties with France.

Yes, his affiliation with the Federalist Party shaped his policies, including the Alien and Sedition Acts, which were controversial and contributed to the party’s decline during his presidency.