Transcription is a complex process that involves the synthesis of RNA molecules from a DNA template. It is a fundamental step in gene expression, and various factors, such as transcription factors, play a role in regulating this process. The correct sequence of nucleotides is crucial, as is the direction of synthesis, which occurs from 5' to 3' for both DNA and RNA. The termination of transcription is equally important and can be influenced by factors like Rho in prokaryotes and Rat1 in yeast. In this response, we will explore the truths behind the following statements related to transcription.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Transcription factors | They regulate the synthesis of DNA in response to a signal |

| They initiate the epinephrine response in animal cells | |

| They control which genes are expressed | |

| They are needed to regulate the synthesis of lipids in the cytoplasm | |

| Some transcribe ATP into cAMP | |

| They control which genes are expressed | |

| Transcription in prokaryotes | The production of a single RNA transcript for a group of related genes is under the control of the repressible operon |

| Transcription terminates as soon as rho has bound to the RNA | |

| Transcription in yeast | Transcription terminates as soon as Rat1 has bound to the RNA |

| Transcription in eukaryotes | There is no one generic promoter |

| A group of genes is transcribed into a polycistronic RNA | |

| Chromatin remodeling is necessary before certain genes are transcribed | |

| There are several different types of RNA polymerase | |

| The TATA-binding protein (TBP) binds to the TATA box sequence in eukaryotic promoters |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Transcription factors regulate DNA synthesis

Transcription factors (TFs) are proteins that play a crucial role in regulating DNA synthesis by controlling the rate of transcription of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA. TFs achieve this regulation by binding to specific DNA sequences, turning genes on or off, and adjusting their level of activity. TFs can act as activators or repressors, influencing the recruitment of RNA polymerase, which is essential for transcription.

TFs contain at least one DNA-binding domain (DBD) that attaches to the DNA sequence adjacent to the genes they regulate. The presence of the DBD is a defining feature of TFs, distinguishing them from other proteins involved in gene regulation. The binding of TFs to DNA is not sufficient for gene expression; they also need to interact with partner proteins. TFs work in a coordinated manner with other proteins to ensure the precise control of gene expression.

The regulation of gene expression by TFs is a dynamic process. TFs can up-regulate or down-regulate transcription through various mechanisms. One mechanism involves stabilizing or blocking the binding of RNA polymerase to DNA, influencing the accessibility of DNA for transcription. Another mechanism entails catalyzing the acetylation or deacetylation of histone proteins, which can either weaken or strengthen the association between DNA and histones, respectively.

In eukaryotes, general transcription factors (GTFs) are essential for transcription. Interestingly, some GTFs do not bind directly to DNA but are part of a larger transcription preinitiation complex that interacts with RNA polymerase. This complex binds to promoter regions of DNA upstream of the regulated gene. The presence of enhancer regions in DNA also plays a role in gene regulation, as they provide binding sites for TFs, allowing them to modulate gene expression in response to the changing requirements of the organism.

TFs are of significant interest in medicine due to their potential therapeutic applications. Mutations in TFs can lead to specific diseases, and medications can be targeted toward these mutations. Furthermore, the discovery that TFs can bind to RNA molecules opens up possibilities for RNA-based therapeutics, as it provides a way to fine-tune gene expression by increasing or decreasing the expression of specific genes.

Identifying Non-Spill Factors: What Doesn't Count as Spillage?

You may want to see also

RNA polymerase synthesises RNA

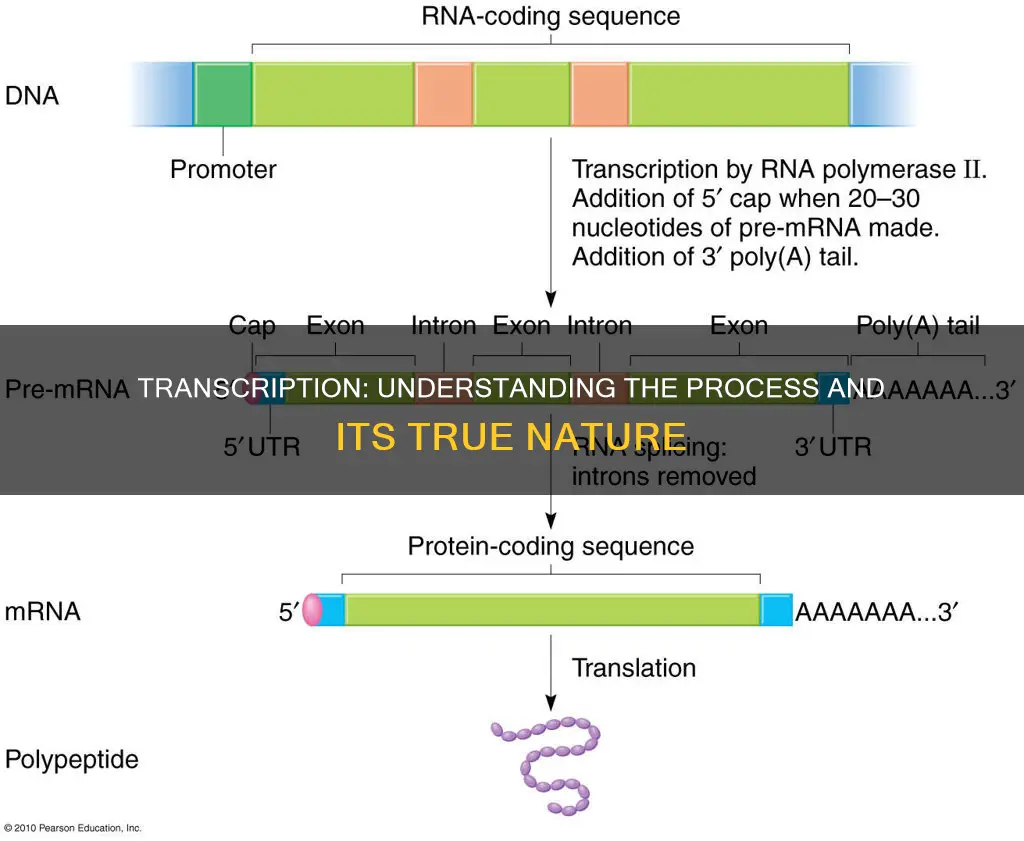

RNA polymerase is an enzyme that plays a crucial role in the process of transcription by synthesising RNA from a DNA template. This enzyme is present in all living organisms and many viruses, making it essential to life. The process of RNA synthesis by RNA polymerase involves several intricate steps, which ensure the accurate transfer of genetic information from DNA to RNA.

The first step in RNA synthesis is initiation. During this stage, RNA polymerase attaches to a specific region on the DNA molecule known as the promoter region. The promoter region acts as a guide, directing RNA polymerase to the correct location for binding, which is usually upstream of a gene. The binding of RNA polymerase to the promoter region is facilitated by transcription factors, which are specialised proteins that regulate gene expression. Once the enzyme successfully binds to the promoter region, it can initiate the unwinding of the double-stranded DNA, exposing a single strand that will serve as a template for RNA synthesis.

The next stage of transcription is elongation. In this phase, RNA polymerase continues its crucial work by using the exposed DNA template strand to build a complementary RNA strand. This process involves the addition of new nucleotides to the growing RNA molecule, following the rules of base pairing dictated by the Watson-Crick model. As RNA polymerase moves along the DNA template, it synthesises an RNA molecule that is an exact copy of the DNA sequence, with the exception that RNA incorporates uracil instead of thymine.

The final stage of transcription is termination. During this stage, RNA polymerase reaches the end of the gene and detaches from the DNA template, releasing the newly synthesised RNA molecule. The termination of transcription can occur in different ways, depending on the organism. In prokaryotes, for example, transcription typically terminates as soon as a specific protein, such as rho, binds to the RNA molecule. In contrast, eukaryotic transcription often involves the presence of a hairpin loop terminator sequence that signals the end of the process.

RNA polymerase exhibits remarkable versatility, with different types of RNA polymerases identified in various organisms. For instance, prokaryotes like bacteria possess a single type of RNA polymerase that transcribes all types of RNA. On the other hand, eukaryotes, including plants and mammals, possess multiple forms of RNA polymerase, each responsible for synthesising a distinct subset of RNA molecules. This diversity in RNA polymerases allows for the synthesis of different types of RNA, such as ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and messenger RNA (mRNA), which play essential roles in gene expression and protein synthesis.

Who Confirms Presidential Cabinet Picks?

You may want to see also

Transcription can terminate past the coding sequence

Transcription is a process fundamental to gene expression and the synthesis of proteins in all living organisms. It involves the creation of RNA molecules from a DNA template, facilitated by RNA polymerase enzymes. The termination of transcription is a critical aspect of this process, ensuring the accurate production of RNA transcripts.

While transcription typically terminates at specific sequences, it is important to note that, in some cases, transcription can extend beyond the coding sequence. This phenomenon, where transcription terminates past the coding sequence, is observed in certain organisms and underscores the dynamic nature of gene expression.

In yeast, for example, transcription termination occurs promptly after the polyadenylation signal (PAS) has been transcribed. This mechanism serves to prevent transcriptional interference on downstream genes, which are often located in close proximity. The yeast's CPF complex, which includes protein phosphatases Ssu72 and Glc7, plays a crucial role in this process.

However, in humans, the behavior of RNAPII differs. Transcription by RNAPII can continue for hundreds or even thousands of nucleotides beyond the PAS before termination occurs. This extension of transcription past the coding sequence is a notable deviation from the typical termination observed in yeast.

The process of transcription termination is highly regulated and involves multiple factors. These factors include initiation, elongation, and termination factors, which are exchanged throughout the transcription cycle. Additionally, the C-terminal domain (CTD) of the largest subunit of RNAPII undergoes differential phosphorylation to facilitate the recruitment and exchange of stage-specific factors.

Workplace Harassment: Abusive Conduct and the Law

You may want to see also

Explore related products

DNA is used as a template for RNA synthesis

Transcription is the process by which cells read out or express the genetic instructions in their genes. DNA is used as a template for RNA synthesis, with one of the two strands of the DNA double helix acting as a template for the synthesis of an RNA molecule. This process is similar to DNA replication, as the nucleotide sequence of the RNA chain is determined by the complementary base pairing between incoming nucleotides and the DNA template. The RNA polymerase enzyme moves stepwise along the DNA, unwinding the helix just ahead of the active site for polymerization to expose a new region of the template strand for complementary base-pairing.

The RNA chain is then extended by one nucleotide at a time in the 5'-to-3' direction. The substrates are nucleoside triphosphates (ATP, CTP, UTP, and GTP), and the energy required to drive the reaction forward is provided by the hydrolysis of high-energy bonds. The RNA strand is almost immediately released from the DNA as it is synthesized, allowing many RNA copies to be made from the same gene in a short time. This process is also known as transcription.

The final product of a minority of genes is the RNA itself, with the majority of genes specifying the amino acid sequence of proteins. The RNA molecules copied from these genes are called messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules, which ultimately direct the synthesis of proteins. RNA can also serve as a template for creating new DNA, RNA, or protein polymers during replication, transcription, and translation, respectively.

In summary, DNA is used as a template for RNA synthesis through the process of transcription, which involves unwinding the DNA double helix, complementary base pairing, and the addition of nucleotides to form an RNA molecule. This process allows for the expression of genetic instructions and the synthesis of proteins.

Epilepsy Misconceptions: What's the Real Truth?

You may want to see also

Transcription factors have DNA-binding domains

Transcription factors are a family of versatile proteins that contain multiple specialized regions. They have a region that can bind to DNA, and another that can bind to proteins. Transcription factors help regulate gene expression by turning genes on or off, and increasing or decreasing their level of activity. They do this in partnership with the proteins that they bind to. Transcription factors anchor themselves and their partner proteins to DNA at binding sites in genetic regulatory sequences, bringing together the components that are needed to make gene expression happen.

Transcription factors are modular in nature in all organisms. They have a DNA-binding domain, one or more transcription activation and/or repressor domains, and often a dimerization domain. In many cases, they also have other protein-protein interaction domains. Mapping these functional domains in transcription factors is critical to understanding their molecular function.

The DNA-binding domain (DBD) interacts with the nucleotides of DNA in a DNA sequence-specific or non-sequence-specific manner. Even non-sequence-specific recognition involves some sort of molecular complementarity between protein and DNA. DNA recognition by the DBD can occur at the major or minor groove of DNA, or at the sugar-phosphate DNA backbone. Each specific type of DNA recognition is tailored to the protein's function. For example, the DNA-cutting enzyme DNAse I cuts DNA almost randomly and so must bind to DNA in a non-sequence-specific manner.

The basic leucine zipper (bZIP) domain is found mainly in eukaryotes and to a limited extent in bacteria. The bZIP domain contains an alpha helix with a leucine at every 7th amino acid. If two such helices find one another, the leucines can interact as the teeth in a zipper, allowing dimerization of two proteins. When binding to the DNA, basic amino acid residues bind to the sugar-phosphate backbone while the helices sit in the major grooves. It regulates gene expression.

The evolutionary rewiring of the ribosomal protein transcription pathway modifies the interaction of transcription factor heteromer Ifh1-Fhl1 (interacts with forkhead 1-forkhead-like 1) with the DNA-binding specificity element.

Executive Power: Why the Unmatched Authority?

You may want to see also