The citric acid cycle, also known as the Krebs cycle, involves several key metabolites, including citrate, isocitrate, alpha-ketoglutarate, and succinyl CoA. During the cycle, citrate is converted into its isomer, isocitrate, through a reaction that involves the shift of the hydroxyl group. This transformation is significant as it changes the type of alcohol in the molecule, with secondary alcohols being able to undergo oxidation, unlike tertiary alcohols. As such, the distinction between citrate and isocitrate as constitutional isomers is crucial in understanding the metabolic transformations within the citric acid cycle.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Intermediates in the Citric Acid Cycle that are constitutional isomers | Citrate and isocitrate |

| How they differ | Position of the hydroxyl group |

| How isocitrate differs from citrate | Isocitrate is a secondary alcohol, citrate is a tertiary alcohol |

| How isocitrate is formed | Through a reaction that loses and gains a water molecule |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Citrate and isocitrate are isomers

The citric acid cycle, also known as the Krebs Cycle, involves several key metabolites, including citrate and isocitrate. Citrate and isocitrate are isomers, with a difference in the position of their hydroxyl group. Citrate is a tricarboxylic acid formed by the condensation of oxaloacetate and acetyl-CoA. Oxaloacetate, a 4-carbon molecule, initiates the cycle. The addition of an acetyl group to oxaloacetate forms citrate.

Isocitrate, an isomer of citrate, differs in the placement of its hydroxyl group. Isocitrate is formed through a reaction that transforms the structure from a tertiary alcohol in citrate to a secondary alcohol in isocitrate. This distinction is important because secondary alcohols can undergo oxidation, while tertiary alcohols cannot. Isocitrate is then converted to alpha-ketoglutarate, a 5-carbon compound, through oxidative decarboxylation.

The citric acid cycle is a crucial metabolic pathway that plays a significant role in the final steps of carbon skeleton oxidative catabolism for carbohydrates, amino acids, and fatty acids. Each metabolite in the cycle typically features carboxylate groups, except for succinyl CoA, which lacks these groups on both ends of its molecule. This distinction sets succinyl CoA apart from other intermediates in the cycle.

Understanding the structures and transformations of metabolites in the citric acid cycle is essential for comprehending the metabolic transformations and energy dynamics within the cycle. The cycle involves a series of reactions that lead to the regeneration of oxaloacetate, completing the cycle.

Understanding Fictitious Business Names and Their Legal Requirements

You may want to see also

Isocitrate and alpha-ketoglutarate conversion

The Citric Acid Cycle, also known as the Krebs Cycle, involves several key metabolites, including isocitrate and alpha-ketoglutarate. These two metabolites are of particular interest as they are isomers, differing in the position of their hydroxyl group. Understanding the conversion between these two intermediates is crucial for comprehending the metabolic transformations within the cycle.

The transition from isocitrate to alpha-ketoglutarate is a key step in the Citric Acid Cycle. This conversion is catalysed by the enzyme isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH), which facilitates the oxidative decarboxylation of isocitrate. The reaction is often irreversible due to its large negative change in free energy, and it must be carefully regulated to avoid depletion of isocitrate and a subsequent accumulation of alpha-ketoglutarate.

The necessary reactants for this enzyme-catalysed process are isocitrate, NAD+ or NADP+, and Mg2+ or Mn2+. During the reaction, isocitrate undergoes oxidative decarboxylation, resulting in the formation of alpha-ketoglutarate, carbon dioxide, and NADH + H+ or NADPH + H+. This reaction involves the oxidation of the alpha-carbon of isocitrate, where the alcohol group is deprotonated, forming a ketone group. NAD+ or NADP+ acts as an electron-accepting cofactor, collecting the resulting hydride.

The oxidation of the alpha-carbon initiates a molecular rearrangement where electrons flow from the nearby carboxyl group, pushing electrons from the double-bonded oxygen up onto the oxygen atom itself. This oxygen atom then collects a proton from a nearby tyrosine group. The carboxyl group oxygen is deprotonated, and electrons flow to the ketone oxygen attached to the alpha-carbon, forming an alpha-beta unsaturated double bond between carbons 2 and 3.

In summary, the conversion of isocitrate to alpha-ketoglutarate is a pivotal step in the Citric Acid Cycle, facilitated by the enzyme isocitrate dehydrogenase. This reaction involves the oxidation and decarboxylation of isocitrate, resulting in the formation of alpha-ketoglutarate and other products. Careful regulation of this process is essential to maintain the balance of intermediates within the cycle.

Critiquing the Constitution: Three Key Flaws

You may want to see also

Alpha-ketoglutarate's role in amino acid synthesis

The citric acid cycle, also known as the Krebs cycle, involves several key metabolites, including alpha-ketoglutarate. Alpha-ketoglutarate is an intermediate in the citric acid cycle and plays a crucial role in amino acid synthesis.

Alpha-ketoglutarate is a 5-carbon compound formed by the oxidative decarboxylation of isocitrate, another metabolite in the citric acid cycle. This conversion is a key step in the cycle, as it leads to the formation of other important metabolites.

Outside of the citric acid cycle, alpha-ketoglutarate is synthesised through glutaminolysis. In this process, the enzyme glutaminase removes the amino group from glutamine to form glutamate, which is then converted to alpha-ketoglutarate by enzymes such as glutamate dehydrogenase, alanine transaminase, or aspartate transaminase.

Alpha-ketoglutarate is directly involved in the synthesis of amino acids such as glutamine, proline, arginine, and lysine. It contributes to the regulation of cellular levels of carbon, nitrogen, and ammonia. This regulatory function is essential for preventing the accumulation of excessive levels of these elements, which could be toxic to cells and tissues.

Additionally, alpha-ketoglutarate is a precursor to glutamate, which is another important amino acid. The synthesis of glutamate from alpha-ketoglutarate involves the transfer of the −NH2 group from an amino acid to alpha-ketoglutarate, forming glutamate and the amine-containing product of alpha-ketoglutarate. This process is crucial for removing excess ammonia from the body through the urea cycle.

Furthermore, alpha-ketoglutarate is involved in amino acid synthesis in industrial applications. For example, using Y. lipolytica as a producer of alpha-ketoglutarate yields a significant amount when n-paraffins are used as carbon sources. However, the high cost of paraffin hinders the widespread use of this method.

Napoleon's Hand in France's Fifth Constitution

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Succinyl CoA's unique structure

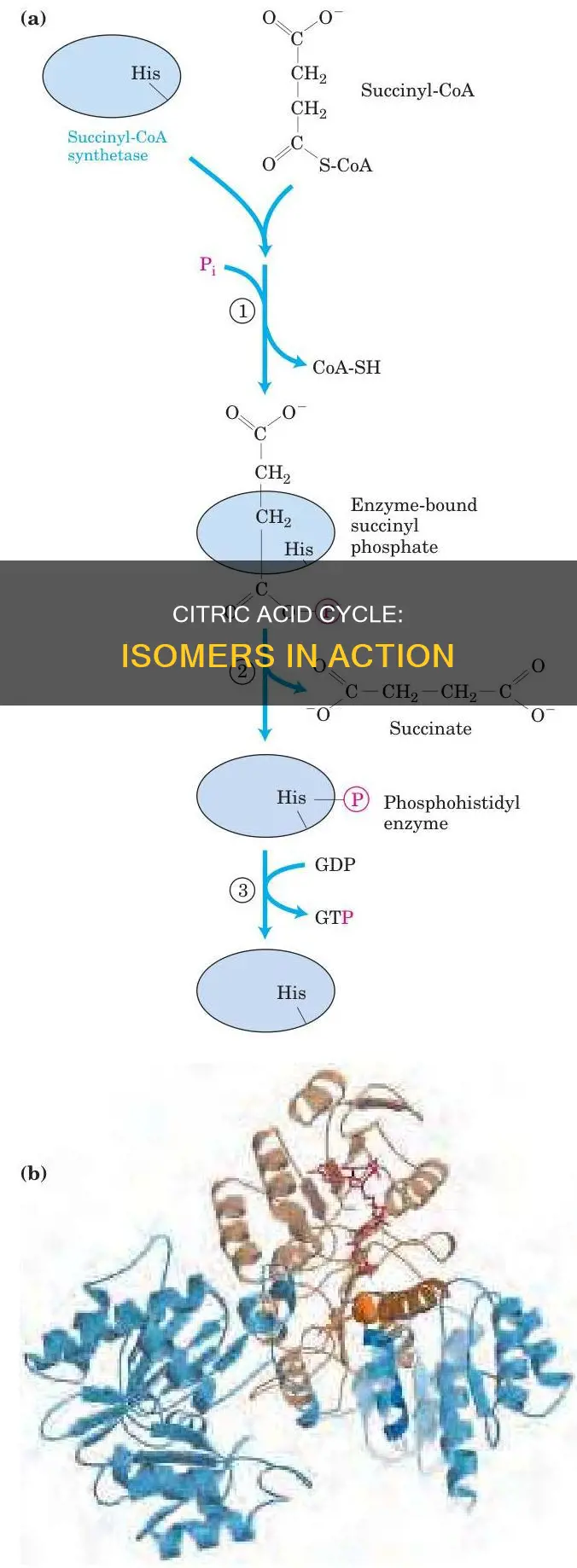

Succinyl CoA is a key metabolite in the Citric Acid Cycle, also known as the Krebs Cycle. It is formed from alpha-ketoglutarate through oxidative decarboxylation, resulting in a 4-carbon compound. Its structure is unique within the cycle as it is the only metabolite that does not have carboxylate groups on both ends of its molecule. This feature distinguishes it from other intermediates, which typically exhibit carboxylate groups.

The distinct structure of Succinyl CoA, including the absence of carboxylate groups, is essential for its function in the cycle. Succinyl CoA undergoes a conversion to succinate, releasing energy that is utilised for the synthesis of ATP or GTP. This process is facilitated by the enzyme succinyl-CoA synthetase, also known as succinate thiokinase. The enzyme catalyses the reversible conversion of Succinyl CoA to succinate, playing a crucial role in energy production.

Furthermore, the structure of Succinyl CoA includes a thioester bond with coenzyme A. This bond is vital for the subsequent conversion of Succinyl CoA to succinate. The thioester bond with coenzyme A also highlights the role of Succinyl CoA in the synthesis of porphyrin and haem. In the porphyrin synthesis pathway, Succinyl CoA combines with glycine to form δ-aminolevulinic acid (dALA), a crucial step in haemoglobin biosynthesis.

The versatility of Succinyl CoA extends beyond the Citric Acid Cycle, as it is involved in various metabolic processes. Succinyl CoA is a precursor for heme synthesis in animals, contributing to essential biological functions. Additionally, Succinyl CoA plays a role in the degradation of several amino acids, odd-chain fatty acids, and cholesterol through the propionyl-CoA pathway. The 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex catalyses the conversion of 2-oxoglutarate to Succinyl CoA and carbon dioxide, further emphasising the importance of Succinyl CoA in metabolic transformations.

In summary, Succinyl CoA's unique structure, characterised by the absence of carboxylate groups on both ends, is pivotal within the Citric Acid Cycle. This structure enables its conversion to succinate, releasing energy for ATP or GTP synthesis. Additionally, the thioester bond with coenzyme A is crucial for subsequent reactions and highlights Succinyl CoA's role in porphyrin and haem synthesis. Beyond the Citric Acid Cycle, Succinyl CoA is involved in heme synthesis in animals and the degradation of various metabolites, showcasing the significance of its structural characteristics in multiple biological processes.

Why the Constitution Was Created: Leaders' Motivations

You may want to see also

Malate, fumarate, and oxaloacetate regeneration

The Citric Acid Cycle, also known as the Krebs Cycle, is a crucial metabolic pathway that involves several key metabolites, including oxaloacetate, citrate, isocitrate, alpha-ketoglutarate, succinyl CoA, succinate, fumarate, and malate. These intermediates play a significant role in regenerating oxaloacetate, completing the cycle.

The regeneration of oxaloacetate occurs through a series of reactions starting from succinyl CoA, which is formed from alpha-ketoglutarate through oxidative decarboxylation. Succinyl CoA is then converted to succinate, releasing energy that contributes to ATP synthesis. This energy is crucial for understanding the cycle's energy dynamics.

Succinate undergoes further transformation to fumarate, which can be converted back to succinate by the enzyme fumarase. Additionally, fumarate can be synthesized into malate, a tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle metabolite. This conversion is facilitated by malate dehydrogenase, resulting in the concurrent reduction of NAD to NADH. Malate can be transported directly into the mitochondrion, where it plays a role in energy production.

Malate can also undergo oxidative decarboxylation with the malic enzyme, producing pyruvate, CO2, and NADPH. Pyruvate is then transported back into the mitochondrion and converted to oxaloacetate by pyruvate carboxylase. This completes the regeneration process, as oxaloacetate is a crucial starting point for the Citric Acid Cycle.

The regeneration of oxaloacetate, along with the other intermediates, ensures the continuous operation of the Citric Acid Cycle. This cycle is essential for the final steps in carbon skeleton oxidative catabolism for carbohydrates, amino acids, and fatty acids. Additionally, the cycle provides insights into the molecular precursors of life, as evidenced by studies in deep space and metabolic evolution.

The Constitution's Article III: Federal Courts' Power Source

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Citric Acid Cycle, also known as the Krebs Cycle, involves several key metabolites: oxaloacetate, citrate, isocitrate, alpha-ketoglutarate, succinyl CoA, succinate, fumarate, and malate.

Citrate and isocitrate are isomers in the Citric Acid Cycle, differing in the position of their hydroxyl group.

The single pathway is referred to by three names: the Citric Acid Cycle (for the first intermediate formed, citric acid or citrate), the TCA cycle (as citric acid or citrate and isocitrate are tricarboxylic acids), and the Krebs Cycle, named after Hans Krebs, who first identified the steps in the 1930s in pigeon flight muscles.

![Essencea Citric Acid 5LB Pure Bulk Ingredients | Non-GMO | 100% Pure Citric Acid Powder [Packaging May Vary]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51O7Lk96ljL._AC_UL320_.jpg)