Drugs interact with the body in a variety of ways, and one of the most common mechanisms is through receptors. Agonists and antagonists are two terms used to describe how a drug interacts with receptors in the body. An agonist drug binds to a receptor and activates it, mimicking the effects of the body's natural ligands or neurotransmitters. On the other hand, an antagonist drug binds to a receptor but does not activate it. Instead, it blocks or opposes the action of other ligands, agonists, or neurotransmitters by rendering the receptors ineffective. Antagonist drugs are often used to treat drug addiction by blocking the euphoric effects of addictive drugs. For example, Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist that blocks the receptors activated by opioids, preventing the euphoric effects and reducing cravings. Therefore, a drug that does not act as an antagonist would be one that does not bind to a receptor without activating it or inhibiting its activity.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A drug that binds to a receptor and activates it, mimicking the effects of the body's natural ligands |

| Action | Agonists turn the receptors on |

| Types | Direct binding agonists, indirect agonists |

| Examples | Opioid drugs like heroin and methadone, apomorphine, cocaine |

| Antagonists | Antagonists oppose the action of agonists by binding to the receptor and blocking it |

| Antagonist Examples | Naltrexone, naloxone, atropine |

Explore related products

$21.06 $26.99

$99 $109.99

What You'll Learn

Agonists and antagonists

Receptors are protein molecules present on the cell surface in the human body. They receive signals (chemical information) from outside the cell. This information comes from other molecules such as hormones, neurotransmitters, and drugs. An agonist is a drug that binds to a receptor and activates it, mimicking the effects of the body's natural ligands. It can have a full or high efficacy on the receptor. A partial agonist also binds to a receptor but only partially activates it. It has lower efficacy than a full agonist. An agonist can be natural or artificial. Natural agonists are hormones or neurotransmitters, while artificial agonists are drugs that are designed to resemble natural agonists. These drugs contain molecules that bind to specific receptors on cells and cause them to become active. Examples of agonists include morphine, methadone, oxycodone, heroin, fentanyl, and endorphins. The physiological responses caused by agonist drugs may include pain relief, changes in mood or cognition, alterations in heart rate or blood pressure, relaxation of smooth muscles, or modulation of hormone release.

An antagonist, on the other hand, binds to a receptor but does not activate it. Instead, it blocks or interferes with the action of other ligands and drugs. In other words, an antagonist works by blocking the activity of an agonist. Antagonists inhibit or oppose the action of an agonist by binding to a cell and making it difficult for the agonists to bind to the cell receptor appropriately. Antagonist drugs block or oppose the natural action or response of a receptor. Examples of antagonists include naltrexone and naloxone, which is used to treat opioid overdoses.

It is important to note that some agonists can act as partial antagonists, but an antagonist drug cannot act as an agonist. Additionally, the intensity and duration of the effects of agonist drugs depend on various factors, such as the drug's potency and dosage.

PO Box vs Branch Office: What's the Legal Difference?

You may want to see also

How agonists work

Agonists are drugs or chemical agents that work by binding to receptors on cells and activating them, thus mimicking the effects of the body's natural ligands. They can be natural or artificial. Endorphins, for example, are natural agonists of opioid receptors, while morphine is an artificial agonist.

Agonists can be further classified as full agonists or partial agonists. Full agonists are capable of producing a maximal response of 100% Emax, representing the point where all available receptors are bound to an agonist. On the other hand, partial agonists, even at very high doses, result in a smaller response, so their Emax will be lower. For example, a 70% response would shift the curve downwards.

The potency of an agonist is inversely related to its half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) value. The EC50 value is useful for comparing the potency of drugs with similar efficacies producing physiologically similar effects. The smaller the EC50 value, the greater the potency of the agonist, and the lower the concentration of the drug required to elicit the maximum biological response.

The process of binding is unique to the receptor-agonist relationship, and binding induces a conformational change and activates the receptor. This conformational change is often the result of small changes in charge or changes in protein folding when the agonist is bound. For example, the binding of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine to the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor causes conformational changes that propagate a signal into the cell.

In summary, agonists work by binding to specific receptors on cells and activating them, either fully or partially, resulting in a biological response. The potency of an agonist depends on its EC50 value, and the process of binding induces conformational changes in the receptor.

Understanding the Formation of India's Upper and Lower Houses

You may want to see also

How antagonists work

Receptors are specialised proteins found inside cells or on their membranes. They receive signals (chemical information) from outside the cell. This information comes from other molecules such as hormones, neurotransmitters, and drugs.

An agonist is a drug that binds to a receptor and activates it, mimicking the effects of the body's natural ligands. In contrast, an antagonist is a medication that typically binds to a receptor without activating it, but instead, decreases the receptor's ability to be activated by another agonist. Antagonists block or oppose the natural action or response of a receptor. They are sometimes called blockers; examples include alpha blockers, beta blockers, and calcium channel blockers.

Competitive antagonists are a type of receptor antagonist that reversibly binds to the same receptor site as an agonist but does not activate it. They typically bind to the receptor in a reversible way, meaning that they bind and dissociate from it pretty fast. So when they unbind, it’s more likely for one of the ligands to bind. This is sometimes referred to as surmountability.

The potency of an antagonist is usually defined by its half maximal inhibitory concentration (i.e., IC50 value). This can be calculated for a given antagonist by determining the concentration of antagonist needed to elicit half inhibition of the maximum biological response of an agonist.

An inverse agonist is a drug that produces an effect similar to that of an antagonist, but causes a distinct set of downstream biological responses. Inverse agonists not only block the effects of binding agonists but also inhibit the basal activity of the receptor.

Washington's Influence on the Constitution

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$180

Types of agonists

Agonists and antagonists are two terms commonly used in pharmacology to refer to drugs or chemical agents that work in opposite ways. An agonist produces a response by binding to a receptor on a cell, whereas an antagonist blocks the receptors and renders them ineffective. An agonist can be natural or artificial.

Natural Agonists

Natural agonists are hormones or neurotransmitters that bind to specific receptors on cells and cause them to become active. Endorphins, for example, are natural agonists for opioid receptors. They bind to opioid receptors and produce the effect of pain relief. Serotonin is another example of a natural agonist. It is a natural neurotransmitter or chemical messenger in the brain and is a natural agonist for the 5-HT2A receptors.

Artificial Agonists

Artificial agonists are drugs that are made to resemble natural agonists. They contain molecules that bind to specific receptors on cells and cause them to become active. Morphine, for instance, is an artificial agonist of opioid receptors. It produces pain relief or a "high" by mimicking the action of the natural agonist. Albuterol is another example of an artificial agonist. It binds to the beta-2 adrenergic receptors in the lungs, causing bronchodilation (widening of airways), which makes it easier to breathe.

Direct Binding Agonists

Direct binding agonists bind directly to the receptor at the same binding site as natural ligands. This results in a faster response. Morphine and methadone are examples of direct binding agonists.

Indirect Binding Agonists

Indirect binding agonists promote the binding of the natural ligand to the receptor site, resulting in a delayed response. Buprenorphine, a medication used to treat drug addiction to opioids, is an example of an indirect binding agonist.

Felon Voting Bans: Unconstitutional?

You may want to see also

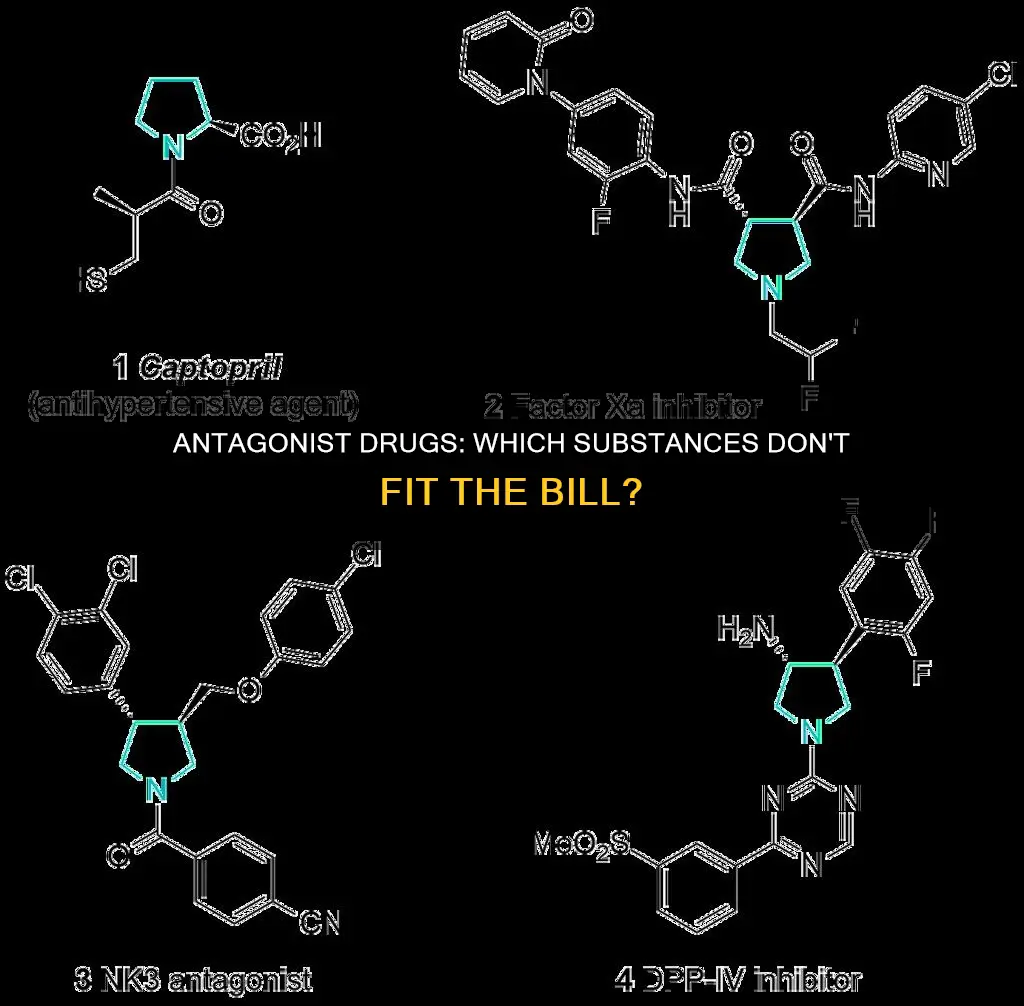

Types of antagonists

Antagonists are drugs or chemical agents that oppose the action of agonist drugs by binding to receptors and blocking their activation. They can be further categorized into two types: direct and indirect acting antagonists.

Direct Acting Antagonists

Direct acting antagonists bind to and block neurotransmitter receptors, preventing neurotransmitters from attaching to the receptors. An example of a direct-acting antagonist is the drug atropine.

Indirect Acting Antagonists

Indirect acting antagonists prevent the production or release of neurotransmitters. An example of an indirect antagonist is reserpine, an anti-psychotic medication used to treat psychotic symptoms and high blood pressure.

Competitive Antagonists

Competitive antagonists are a type of medication that reversibly binds to the same receptor site as an agonist but does not activate it. They typically bind to the receptor in a reversible way, allowing them to bind and dissociate quickly. This increases the likelihood of ligands binding when they unbind. Buprenorphine, a medication used to treat drug addiction to opioids, is an example of a competitive antagonist.

Inverse Agonists

Inverse agonists produce the opposite effect of agonists by binding to a receptor and decreasing its activity below the baseline. Antihistamine medications, for instance, have some inverse agonist activity.

Criminal Behavior: What's Easy to Define?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

An agonist is a drug that binds to a receptor and activates it, mimicking the effects of the body's natural ligands. An antagonist, on the other hand, binds to a receptor but does not activate it. Instead, it blocks or opposes the action of other ligands and drugs.

Some examples of agonist drugs include opioid drugs such as heroin, methadone, oxycodone, morphine, fentanyl, and endorphins.

Some examples of antagonist drugs include naltrexone, naloxone, and atropine.