The topic of corporate political donations has become increasingly scrutinized as businesses wield significant influence over political landscapes. Many companies across various industries contribute financially to political parties, often through Political Action Committees (PACs) or direct donations, aiming to shape policies that align with their interests. These contributions can range from small local businesses to multinational corporations, with sectors like finance, energy, and technology being among the most prominent donors. Understanding which companies donate to political parties is crucial for transparency, as it sheds light on potential conflicts of interest and the broader implications of corporate money in politics. Public records, such as those maintained by the Federal Election Commission (FEC) in the United States, provide valuable insights into these donations, allowing citizens and watchdog groups to hold both corporations and politicians accountable.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Corporate Political Action Committees (PACs)

Analyzing the mechanics of PACs reveals their strategic design. Contributions to PACs are voluntary and typically sourced from employees, executives, and shareholders, with individual donations capped by federal limits (currently $5,000 per person per year). The PAC then consolidates these funds and disburses them to candidates or political organizations, often based on alignment with the company’s policy priorities. For example, energy companies like ExxonMobil use their PACs to support lawmakers who advocate for deregulation or fossil fuel subsidies, while tech giants like Microsoft focus on candidates pushing for favorable immigration or trade policies. This targeted approach ensures that corporate interests are amplified in political arenas.

However, the rise of PACs has sparked ethical debates and regulatory scrutiny. Critics argue that they enable corporations to wield disproportionate influence over lawmakers, creating a pay-to-play system that undermines democratic principles. The Citizens United v. FEC Supreme Court decision in 2010 further exacerbated this issue by allowing unlimited corporate spending on political advertising through Super PACs, which, while legally distinct from traditional PACs, blur the lines of corporate political involvement. Transparency efforts, such as mandatory disclosure of PAC contributions, aim to mitigate these concerns, but loopholes and lax enforcement often leave the public in the dark about the full extent of corporate political spending.

For businesses considering forming a PAC, several practical steps and cautions are essential. First, establish clear objectives aligned with the company’s long-term interests, such as tax policy, regulatory reform, or industry-specific legislation. Second, ensure compliance with Federal Election Commission (FEC) rules, including registration, reporting, and contribution limits. Third, communicate transparently with employees and stakeholders about the PAC’s activities to avoid backlash or perceptions of coercion. Finally, monitor public sentiment and adjust strategies accordingly, as high-profile PAC donations can attract media scrutiny and damage a company’s reputation if misaligned with public values.

In conclusion, Corporate PACs are a double-edged sword in the realm of political donations. While they provide a structured avenue for businesses to advocate for their interests, they also raise questions about fairness, transparency, and the integrity of the political process. Companies must navigate this landscape carefully, balancing strategic influence with ethical responsibility to maintain trust with consumers, employees, and the public at large.

Is Centrism a Political Party? Debunking Misconceptions and Understanding Its Role

You may want to see also

Industry-specific donations (e.g., tech, energy, finance)

Corporate political donations often align with industry priorities, creating a symbiotic relationship between business interests and legislative outcomes. In the tech sector, for instance, companies like Google, Microsoft, and Amazon consistently rank among the top corporate donors. Their contributions frequently target issues such as data privacy regulations, immigration policies for skilled workers, and antitrust legislation. By investing in political campaigns, these tech giants aim to shape policies that foster innovation while mitigating regulatory hurdles that could stifle growth. For example, Google’s political action committee (PAC) has donated millions to both Democratic and Republican candidates, reflecting a strategy to maintain influence across the political spectrum.

In contrast, the energy industry’s donations often reflect its dual focus on traditional fossil fuels and emerging renewable technologies. ExxonMobil, Chevron, and other oil and gas companies have historically supported candidates who advocate for deregulation and expanded drilling rights. Meanwhile, renewable energy firms like NextEra Energy and Tesla increasingly contribute to politicians pushing for green energy subsidies and climate legislation. This industry’s donations highlight a divide: traditional players seek to protect existing revenue streams, while newer entrants aim to accelerate the transition to sustainable energy. Notably, energy companies often donate to both parties, strategically hedging their bets in a politically polarized environment.

The finance industry’s political contributions are equally strategic, with Wall Street firms like Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, and Citigroup consistently ranking as top donors. These companies focus on issues such as tax policy, financial regulation, and trade agreements. For example, during debates over the Dodd-Frank Act, financial institutions lobbied heavily against stringent regulations that could impact profitability. Their donations often skew toward candidates who support lower corporate taxes and deregulation, though there’s a growing trend of contributions to politicians advocating for consumer protection measures to improve public perception.

A comparative analysis reveals that while all three industries—tech, energy, and finance—donate heavily, their motivations differ. Tech companies prioritize innovation and regulatory flexibility, energy firms navigate the tension between fossil fuels and renewables, and financial institutions focus on tax and regulatory environments. Each industry tailors its donations to secure favorable policies, demonstrating how corporate giving is a calculated investment in future legislative landscapes.

Practical takeaways for understanding industry-specific donations include tracking PAC filings, analyzing lobbying efforts alongside contributions, and examining how policy changes correlate with donation patterns. For instance, a spike in tech donations during debates over Section 230 reforms can signal industry concern. Similarly, energy donations often surge during discussions of carbon taxes or drilling permits. By scrutinizing these trends, stakeholders can better grasp the interplay between corporate money and political outcomes, fostering greater transparency in the democratic process.

Exploring Socialism's Political Landscape: Do Parties Play a Role?

You may want to see also

Transparency and disclosure laws

Corporate political donations often operate in the shadows, but transparency and disclosure laws aim to pull them into the light. These laws mandate that companies and organizations reveal their political contributions, ensuring the public can see who is influencing the political process. For instance, in the United States, the Federal Election Campaign Act requires corporations to disclose donations to candidates, parties, and Political Action Committees (PACs). Similarly, the UK’s Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 mandates reporting donations above £7,500. Such laws serve as a critical check on corporate influence, allowing voters to hold both businesses and politicians accountable.

However, the effectiveness of these laws hinges on their enforcement and the granularity of the required disclosures. In some jurisdictions, loopholes allow companies to funnel money through intermediary organizations, obscuring the true source of funds. For example, "dark money" groups in the U.S., often registered as social welfare organizations, can accept unlimited corporate donations without disclosing donors. This undermines transparency, as the public cannot trace the money back to its corporate origins. Strengthening enforcement mechanisms and closing such loopholes are essential to ensure these laws fulfill their intended purpose.

Another challenge lies in the accessibility and usability of disclosed information. While data on political donations may be publicly available, it is often buried in complex databases or filed in formats difficult for the average citizen to interpret. Governments and watchdog organizations can improve this by creating user-friendly platforms that aggregate and visualize donation data. For instance, the U.S. Federal Election Commission’s database could be enhanced with searchable filters, interactive charts, and real-time updates, making it easier for journalists, researchers, and voters to analyze corporate influence.

Ultimately, transparency and disclosure laws are only as strong as the public’s ability to engage with the information they provide. Education campaigns can play a vital role in empowering citizens to use this data effectively. Workshops, online tutorials, and media coverage can teach people how to track corporate donations, identify patterns of influence, and advocate for policy changes. By combining robust laws with accessible tools and public awareness, societies can mitigate the risks of corporate money in politics and foster a more democratic political landscape.

The Party of Slaveholders: Representing the Interests of Southern Planters

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$2.99 $17.99

Influence on policy and legislation

Corporate donations to political parties often come with strings attached, shaping policy and legislation in ways that favor the donor’s interests. For instance, pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer and Merck have historically contributed millions to both Democratic and Republican campaigns, coinciding with favorable drug pricing policies and reduced regulatory scrutiny. This quid pro quo dynamic raises ethical questions but also highlights a practical reality: financial contributions grant companies access to lawmakers, enabling them to advocate for policies that protect or expand their profit margins.

To understand the mechanics of this influence, consider the energy sector. Companies like ExxonMobil and Chevron have donated extensively to political parties, particularly those advocating for fossil fuel interests. These contributions often align with legislative outcomes, such as tax breaks for oil exploration or weakened environmental regulations. While not always direct, the correlation between donations and policy shifts suggests a strategic investment in shaping laws that benefit the industry. For businesses, this is a calculated move; for the public, it’s a reminder of the need for transparency and accountability.

A persuasive argument can be made that such influence undermines democratic principles, but it’s also a call to action for citizens and policymakers. Voters can pressure representatives to disclose donor ties and reject contributions from industries with clear conflicts of interest. Policymakers, in turn, can implement stricter campaign finance laws, such as caps on corporate donations or mandatory waiting periods between lobbying activities and legislative votes. These steps could reduce the outsized role of money in politics and restore balance to the policymaking process.

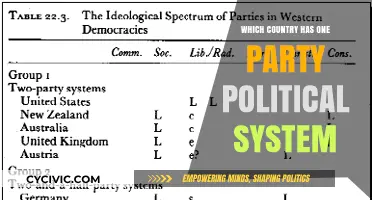

Comparatively, countries with stricter campaign finance regulations, like Canada and the UK, offer models for mitigating corporate influence. In Canada, for example, corporations and unions are prohibited from donating to political parties, limiting their ability to sway policy. While no system is perfect, these examples demonstrate that legislative safeguards can curb the disproportionate power of corporate donors. For the U.S., adopting similar measures could be a first step toward reclaiming policy decisions for the public good rather than private profit.

Understanding Sectarian Rejection of Political Islam: Causes and Implications

You may want to see also

Public perception and brand reputation impact

Corporate political donations often become a double-edged sword, particularly when scrutinized through the lens of public perception. A single contribution can spark viral outrage or earn quiet admiration, depending on the alignment with consumer values. For instance, when a tech giant donates to a party advocating for stricter data privacy laws, its customer base—largely privacy-conscious millennials and Gen Z—may view this as a principled stand. Conversely, a fossil fuel company funding climate change denial campaigns risks alienating eco-aware consumers, even if the donation is legally sound. The key lies in understanding that transparency isn’t enough; the *why* behind the donation matters more than the *what*. Companies must articulate how their political investments reflect their brand’s core values, or risk being labeled as opportunistic.

To navigate this minefield, brands should adopt a three-step strategy. First, conduct a values audit to identify which political issues align with their mission and audience priorities. For example, a skincare company might focus on parties supporting chemical regulation in cosmetics. Second, communicate proactively—not just in press releases, but through employee testimonials, social media campaigns, or even product packaging. Third, measure impact via sentiment analysis tools like Brandwatch or Sprinklr to gauge public reaction in real time. Ignoring this step can lead to missteps, such as a retail brand donating to a party opposing minimum wage increases, only to face boycotts from its own low-wage workforce.

A comparative analysis reveals that industries handle this differently. Financial institutions often donate to both major parties to hedge their bets, a strategy that minimizes backlash but also dilutes brand identity. In contrast, tech startups frequently back progressive causes, leveraging their donations to strengthen their image as disruptors. For instance, Patagonia’s public support for environmental candidates has bolstered its reputation as an activist brand, turning political donations into a competitive advantage. This approach works because it’s authentic—the company’s actions align with its decades-long commitment to sustainability.

However, even well-intentioned donations can backfire without careful execution. Take the case of a beverage company that funded a health-focused campaign but was later exposed for lobbying against sugar taxes. The cognitive dissonance eroded trust, proving that isolated donations cannot offset contradictory corporate behavior. To avoid this, companies should adopt a 360-degree alignment policy, ensuring political contributions, lobbying efforts, and public messaging are consistent. For instance, a pharmaceutical company donating to healthcare access initiatives should also disclose efforts to lower drug prices, bridging the gap between perception and reality.

Ultimately, the impact of political donations on brand reputation hinges on one question: Does the public see the company as a stakeholder or a profiteer? Stakeholder brands—those perceived as investing in societal good—reap long-term loyalty. Profiteers, however, face fleeting gains and lasting skepticism. A practical tip for companies is to cap individual donations at a publicly declared threshold, say 5% of annual profits, to signal restraint. Pairing this with a pledge to match employee political contributions can further humanize the brand. In an era where consumers vote with their wallets, such strategies aren’t just ethical—they’re strategic.

Understanding the Role of a Modern Political Scientist Today

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Some of the largest corporate donors to political parties in the U.S. include AT&T, Comcast, Alphabet (Google's parent company), and Goldman Sachs. These companies often contribute through Political Action Committees (PACs) and other legal channels.

No, companies often donate disproportionately based on their interests and the political climate. For example, some industries may favor one party over the other due to policy alignment, such as fossil fuel companies leaning Republican and tech companies leaning Democratic.

Yes, in the U.S., companies cannot donate directly to federal candidates, but they can contribute to PACs, which have limits on donations. Additionally, some states have their own regulations on corporate political donations.

You can use publicly available databases like the Federal Election Commission (FEC) in the U.S. or OpenSecrets.org to track corporate political donations. These platforms provide detailed information on contributors and recipients.

It varies by country. In some nations, corporate political donations are heavily regulated or banned, while in others, they are allowed but with strict transparency requirements. For example, the U.K. permits donations but requires public disclosure.