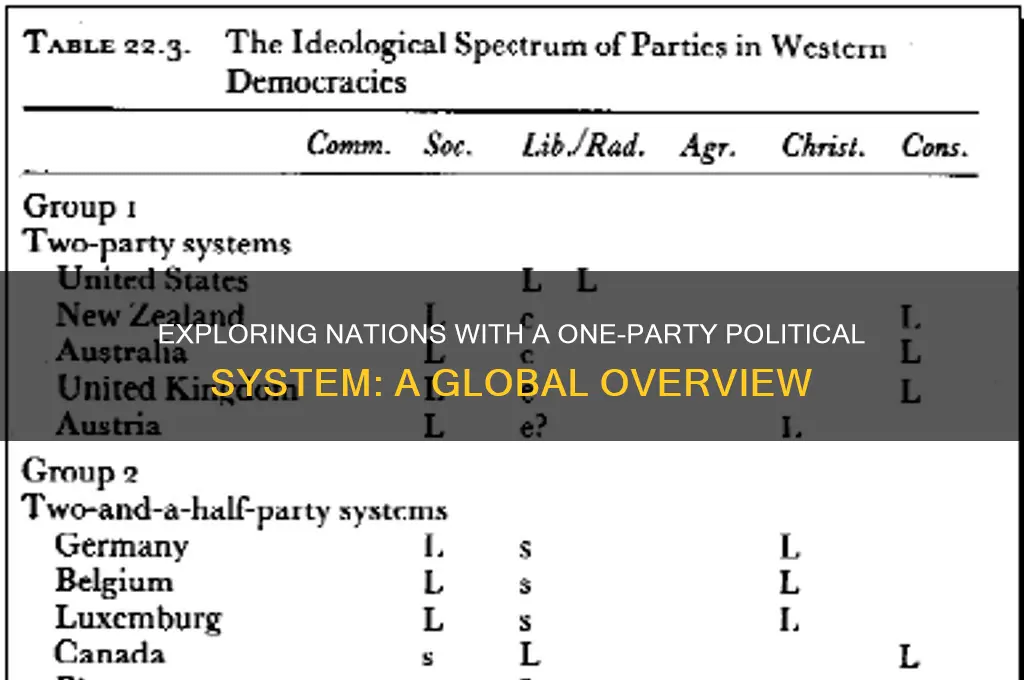

A one-party political system is characterized by the dominance of a single political party, often enshrined in the country's constitution or maintained through various mechanisms to ensure its continued rule. Among the nations that operate under such a system, China stands out as a prominent example, with the Communist Party of China (CPC) holding exclusive political power since 1949. Other countries with one-party systems include Cuba, where the Communist Party of Cuba has been in control since 1959, and North Korea, governed by the Workers' Party of Korea since its founding in 1948. These systems typically limit political opposition, prioritize ideological conformity, and often emphasize stability and centralized decision-making over multiparty competition. Understanding these systems provides insight into the diverse ways in which political power is structured and maintained globally.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- China's Communist Party Dominance: Single-party rule since 1949, controlling all governance levels

- North Korea's Juche Ideology: Workers' Party maintains absolute power under Juche principles

- Vietnam's Communist Leadership: Vietnamese Communist Party governs with no opposition allowed

- Cuba's Revolutionary System: Communist Party of Cuba holds sole political authority

- Laos' One-Party Structure: Lao People's Revolutionary Party controls all political processes

China's Communist Party Dominance: Single-party rule since 1949, controlling all governance levels

China's Communist Party (CCP) has maintained an unbroken grip on power since 1949, establishing a single-party system that permeates every level of governance. This dominance is not merely a formality; it is a meticulously structured and deeply entrenched system. The CCP's control extends from the highest echelons of the central government to the grassroots level, with party committees embedded in all state institutions, including the military, judiciary, and local administrations. This comprehensive control ensures that the party's ideology and policies are uniformly implemented across the country, leaving no room for political opposition or alternative power centers.

To understand the mechanics of this dominance, consider the hierarchical structure of the CCP. At the apex is the Politburo Standing Committee, a small group of individuals who hold the most significant decision-making power. Below this, the party is organized into layers of committees and cells, each responsible for enforcing party directives in their respective domains. This pyramidal structure ensures that the party's influence is both vertical and horizontal, covering all sectors of society. For instance, state-owned enterprises, universities, and even neighborhood communities have party branches that oversee operations and ensure alignment with CCP objectives.

The CCP's ability to maintain this dominance lies in its adaptive strategies. Unlike rigid authoritarian regimes, the CCP has shown a willingness to evolve, incorporating economic reforms while retaining political control. The introduction of market-oriented policies in the late 1970s, for example, allowed China to achieve unprecedented economic growth without loosening the party's grip on power. This pragmatic approach has enabled the CCP to address societal demands for prosperity while neutralizing potential sources of dissent. Additionally, the party employs a sophisticated propaganda apparatus to shape public opinion, promoting the narrative that its leadership is essential for China's stability and progress.

A critical aspect of the CCP's dominance is its control over the state apparatus. The principle of "party leadership" is enshrined in China's constitution, ensuring that the CCP's authority supersedes that of the state. This is evident in the dual leadership system, where party secretaries hold more power than government officials at the same administrative level. For example, a provincial party secretary wields greater influence than the provincial governor, illustrating the party's primacy. This system ensures that the CCP's interests are always prioritized, even in the face of bureaucratic or administrative challenges.

Despite its enduring dominance, the CCP faces challenges that test its single-party rule. Economic disparities, corruption, and growing demands for greater political participation pose risks to its legitimacy. However, the party has demonstrated resilience through anti-corruption campaigns, targeted economic policies, and the suppression of dissent. These measures, while often criticized internationally, have been effective in maintaining internal stability and public support. The CCP's ability to balance control with adaptability remains its most significant strength, ensuring its continued dominance in China's political landscape.

In conclusion, the CCP's single-party rule in China is a complex and multifaceted system that has endured for over seven decades. Its dominance is not merely a result of political suppression but a combination of structural control, adaptive strategies, and ideological cohesion. Understanding this system provides valuable insights into how a single-party regime can sustain itself in a rapidly changing world, offering both lessons and warnings for other political systems globally.

T. Massey's Political Impact: Shaping Policies and Public Opinion

You may want to see also

North Korea's Juche Ideology: Workers' Party maintains absolute power under Juche principles

North Korea stands as a prime example of a one-party political system, where the Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK) wields absolute power under the guiding principles of Juche ideology. This unique framework, developed by Kim Il-sung, emphasizes self-reliance, independence, and national sovereignty. Juche is not merely a political doctrine but a comprehensive worldview that permeates every aspect of North Korean society, from education to foreign policy. It serves as the ideological backbone that justifies the WPK’s unchallenged authority, positioning the party as the sole legitimate representative of the people’s will.

To understand how the WPK maintains its grip on power, consider the practical implementation of Juche principles. The ideology promotes economic self-sufficiency, which translates into policies like Songun (military-first) and a rejection of foreign aid or influence. This isolationist approach ensures that external ideas or political alternatives cannot take root, solidifying the party’s monopoly on power. For instance, state-controlled media exclusively propagates Juche ideals, while dissent is systematically suppressed, often through a pervasive surveillance apparatus. Citizens are taught from a young age that loyalty to the party and its leadership is synonymous with patriotism, creating a culture of conformity that reinforces the one-party system.

A comparative analysis highlights the distinctiveness of North Korea’s model. Unlike other one-party states, such as China or Vietnam, which have introduced market reforms and limited external engagement, North Korea’s Juche ideology demands near-total isolation. This rigidity has led to economic stagnation but has also preserved the WPK’s absolute control. The leadership’s ability to frame external threats—real or perceived—as validation of Juche’s necessity further cements its legitimacy. For example, the ongoing tensions with the United States and South Korea are portrayed as evidence of the need for self-reliance and a strong, unified party.

For those seeking to understand or engage with North Korea, recognizing the centrality of Juche is essential. The ideology is not a mere propaganda tool but a deeply ingrained belief system that shapes policy and public behavior. Any attempt to influence North Korea must navigate this ideological framework, acknowledging its role in sustaining the WPK’s power. Practical tips include focusing on areas where Juche’s emphasis on self-reliance aligns with potential cooperation, such as agricultural technology or healthcare, while avoiding direct challenges to the party’s authority.

In conclusion, North Korea’s Juche ideology is the linchpin of its one-party system, providing both the rationale and the mechanisms for the WPK’s absolute power. Its unique blend of isolationism, militarism, and nationalism ensures that the party remains unchallenged, despite the country’s economic and diplomatic challenges. Understanding Juche is not just an academic exercise but a practical necessity for anyone seeking to comprehend or interact with North Korea’s political landscape.

Scientology's Political Affiliations: Unraveling the Party Connections and Influences

You may want to see also

Vietnam's Communist Leadership: Vietnamese Communist Party governs with no opposition allowed

Vietnam stands as a prominent example of a one-party political system, where the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) holds absolute power, and no opposition parties are permitted. This system, rooted in Marxist-Leninist ideology, has been in place since the country’s reunification in 1976. The CPV’s dominance is enshrined in Article 4 of Vietnam’s Constitution, which explicitly states that the Party is the “leading force of the state and society.” This legal framework ensures that all political activities, policies, and governance structures are directed and controlled by the CPV, leaving no room for alternative political voices.

The CPV’s monopoly on power is maintained through a tightly controlled political apparatus. All candidates for elected positions, from local councils to the National Assembly, must be approved by the Party. While elections do occur, they are largely ceremonial, as the CPV vets and selects candidates who align with its agenda. This process effectively eliminates any possibility of genuine political competition. Additionally, the state exercises strict control over media and civil society, suppressing dissent and ensuring that the Party’s narrative remains unchallenged. Critics argue that this system stifles pluralism and limits the representation of diverse viewpoints, but proponents claim it fosters stability and unity in a country with a history of conflict.

A closer examination of Vietnam’s one-party system reveals both its strengths and limitations. On one hand, the CPV’s centralized control has enabled rapid economic growth and development, particularly since the introduction of market-oriented reforms in the 1980s (known as Đổi Mới). Vietnam has transformed from one of the poorest nations to a middle-income economy, with significant reductions in poverty rates. On the other hand, the lack of political competition has led to issues such as corruption, inequality, and limited accountability. Without opposition parties or independent media to scrutinize the government, addressing these challenges becomes more difficult.

For those studying or engaging with Vietnam’s political system, understanding the CPV’s role is crucial. The Party’s influence extends beyond politics into all aspects of society, including education, culture, and the economy. To navigate this environment effectively, individuals and organizations must recognize the boundaries set by the Party while identifying areas where constructive engagement is possible. For instance, while direct political opposition is not tolerated, advocacy for specific policy reforms or social initiatives may find traction if aligned with the Party’s broader goals of development and stability.

In conclusion, Vietnam’s one-party system under the CPV is a unique political model that prioritizes unity and control over pluralism. While it has facilitated economic progress, its suppression of opposition raises questions about long-term sustainability and governance quality. For observers and participants alike, understanding the intricacies of this system is essential to appreciating Vietnam’s trajectory and engaging meaningfully with its political landscape.

Why Political Parties Rely on Massive Funding: Uncovering the Financial Needs

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Cuba's Revolutionary System: Communist Party of Cuba holds sole political authority

Cuba's political landscape is a unique case study in one-party systems, where the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC) has held sole political authority since the 1959 Revolution. This system, rooted in Marxist-Leninist ideology, is characterized by a centralized structure that permeates all levels of governance. The PCC’s dominance is enshrined in Article 5 of the Cuban Constitution, which declares it the "superior leading force of society and of the state." Unlike multi-party democracies, where power shifts through elections, Cuba’s system ensures continuity of revolutionary ideals through a single, unified party. This framework eliminates political opposition, positioning the PCC as both the architect and enforcer of national policies.

To understand how this system operates, consider its hierarchical design. The PCC’s highest authority is the Party Congress, held every five years, which sets long-term goals and elects the Central Committee. This committee, in turn, appoints the Politburo, a smaller group that makes day-to-day decisions. At the local level, party cells ensure alignment with central directives, creating a vertical chain of command. This structure minimizes dissent and maximizes control, but it also limits avenues for public input outside the party’s framework. For instance, while Cubans participate in municipal elections, candidates are pre-screened by PCC-affiliated committees, ensuring loyalty to the party line.

A critical aspect of Cuba’s one-party system is its integration with mass organizations, such as the Federation of Cuban Women and the Union of Young Communists. These groups act as extensions of the PCC, mobilizing citizens around revolutionary objectives while also serving as surveillance mechanisms. This dual role highlights the system’s ability to foster unity and participation but also raises questions about individual autonomy. For example, membership in these organizations often correlates with access to educational and professional opportunities, creating implicit pressure to conform.

Comparatively, Cuba’s model differs from other one-party states like China or Vietnam, where economic reforms have introduced market elements while maintaining political control. Cuba, however, has retained a more rigid state-controlled economy, aligning closely with its revolutionary ethos. This has resulted in both achievements, such as high literacy rates and universal healthcare, and challenges, including economic stagnation and resource scarcity. The PCC’s insistence on ideological purity has limited pragmatic reforms, underscoring the tension between revolutionary ideals and practical governance.

For those examining Cuba’s system, a key takeaway is its resilience in the face of external pressures, particularly the U.S. embargo. The PCC has framed its sole authority as a necessary shield against foreign interference, fostering a strong national identity. However, this narrative also masks internal complexities, such as generational divides and growing calls for greater political openness. As Cuba navigates the post-Castro era, the PCC’s ability to adapt its one-party model will determine its longevity in a rapidly changing world.

Essential Resources Political Parties Offer Their Candidates for Success

You may want to see also

Laos' One-Party Structure: Lao People's Revolutionary Party controls all political processes

Laos stands as a prime example of a one-party political system, where the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party (LPRP) holds absolute control over all governmental and political processes. Established in 1955, the LPRP has been the sole ruling party since the country’s transition to a Marxist-Leninist state in 1975. This structure ensures that all legislative, executive, and judicial functions are directed by the party’s ideology and leadership, leaving no room for opposition or alternative political voices. The LPRP’s dominance is enshrined in the Lao Constitution, which explicitly states that the party is the “leading nucleus” of the political system, effectively eliminating any possibility of multi-party competition.

Analyzing the mechanics of this system reveals a tightly controlled hierarchy. The LPRP’s Politburo, composed of 13 members, serves as the highest decision-making body, with the General Secretary acting as the de facto leader of both the party and the state. Local governance is similarly structured, with party committees overseeing provincial and district administrations. This vertical integration ensures that policies are uniformly implemented across the country, but it also limits grassroots representation and diversity in decision-making. Critics argue that this centralized control stifles innovation and accountability, as there are no checks and balances from opposing political forces.

From a comparative perspective, Laos’ one-party system shares similarities with other Marxist-Leninist states like China, Vietnam, and Cuba, but it stands out for its lack of even nominal political pluralism. Unlike China’s United Front or Vietnam’s Fatherland Front, which allow for limited participation of non-party organizations, Laos maintains a rigid monopoly on power. This distinction underscores the LPRP’s commitment to maintaining ideological purity and political stability, often at the expense of democratic freedoms. For instance, while Vietnam has experimented with economic reforms and limited political openness, Laos remains firmly closed to such changes.

Practically, the LPRP’s control extends beyond politics into everyday life, influencing education, media, and civil society. State-controlled media outlets exclusively promote party narratives, and dissent is systematically suppressed. For citizens, this means limited access to alternative viewpoints and restricted avenues for political expression. However, the party justifies its dominance by pointing to achievements in poverty reduction and infrastructure development, particularly in rural areas. For those seeking to understand or engage with Laos, it’s essential to recognize this context: the LPRP’s role is not merely political but deeply intertwined with the nation’s identity and development trajectory.

In conclusion, Laos’ one-party structure under the LPRP offers a unique case study in centralized political control. While it ensures stability and uniformity, it also raises questions about representation, accountability, and individual freedoms. For observers and policymakers, understanding this system requires moving beyond simplistic labels of “authoritarianism” to grasp the nuanced ways in which the LPRP shapes Lao society. Whether viewed as a model of efficient governance or a constraint on democratic potential, Laos’ political system remains a critical example in the global discourse on one-party states.

Why I Despise Politics: Unraveling My Frustration with the System

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

China is a prominent example of a country with a one-party political system, where the Communist Party of China (CPC) holds sole governing power.

In North Korea, the Workers' Party of Korea (WPK) dominates all aspects of governance, and other parties, if they exist, are subordinate and aligned with the WPK's agenda.

Yes, countries like Eritrea operate under a one-party system, with the People's Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) as the sole ruling party.