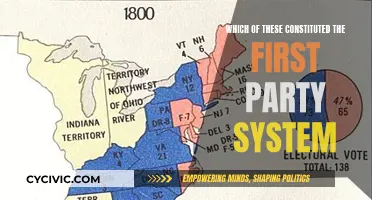

Athenian democracy was a direct democracy made up of three institutions: the ekklesia, a governing body that wrote laws and dictated foreign policy; the boule, a council of representatives from the ten Athenian tribes; and the dikasteria, popular courts where citizens argued cases. In 507 BC, the Athenian leader Cleisthenes introduced a system of political reforms that he called demokratia, or rule by the people. However, the Athenian version of democracy, which started around 460 BC and ended around 320 BC, was considered the most developed. Before the first attempt at democratic government, Athens was ruled by a series of archons or magistrates, and the council of the Areopagus, made up of ex-archons. In 621 BC, Draco replaced the oral law system with a written code to be enforced by a court of law, now known as the Draconian Constitution. In 594 BC, Solon was appointed premier archon and began issuing economic and constitutional reforms to alleviate conflict arising from inequities in Athenian society.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Cleisthenes |

| Known as | "The Father of Democracy" |

| Year of Reforms | 507 B.C. |

| Citizenship | Gave each free resident of Attica a political function |

| Citizenship | Abolished political distinctions between Athenian aristocrats and middle- and working-class people |

| Citizenship | Redefined what it was to be a citizen and removed the influence of traditional clan groups |

| Citizenship | Broadened the government's structure to include a wider range of property classes rather than just the aristocracy |

| Citizenship | Established four property classes: the pentakosiomedimnoi, the hippeis, the zeugitai, and the thetes |

| Political Reforms | Called his system "demokratia" or "rule by the people" |

| Political Reforms | Comprised of three separate institutions: the ekklesia, the boule, and the dikasteria |

| Political Reforms | Redefined citizenship in a way that gave each free resident of Attica a political function |

| Political Reforms | Broke up the unlimited power of the nobility by organizing citizens into ten groups based on where they lived, rather than on their wealth |

| Political Reforms | Granted the formerly aristocratic role to every free citizen of Athens who owned property |

| Political Reforms | Changed Athenian democracy by removing the influence of traditional clan groups |

| Political Reforms | Allowed all citizens to participate in government, not just aristocrats |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Solon's constitutional reforms

Solon, an Athenian statesman, lawmaker, political philosopher, and poet, is credited with writing Athens' first constitution. Serving as archon, or annual chief ruler, in 594 BC, Solon implemented constitutional reforms to address the conflict arising from the inequities in Athenian society.

Solon's constitution was based on four classes: the pentakosiomedimnoi, the hippeis, the zeugitai, and the thetes. These classes were determined by a citizen's census and wealth, specifically, how many medimnoi a man's estate made per year. The pentakosiomedimnoi produced at least 500 medimnoi, the hippeis 300-500, the zeugitai 200-300, and the thetes less than 200. The thetes were the lowest social class of citizens, including wage workers and those with a low yearly income.

Solon's constitution redefined citizenship, granting each free resident of Attica a political function and the right to participate in assembly meetings. By broadening the government's structure beyond the aristocracy, Solon sought to weaken the strong influence of noble families. While Solon retained a hierarchical distribution of political responsibility, he eliminated privilege by birth.

Solon's reforms also impacted the judicial system. He introduced the right for any Athenian to initiate a lawsuit and provided a measure of control over the verdict of magistrates by allowing an appeal to a court of citizens at large. Additionally, Solon's economic reforms, known as the ""shaking off of burdens," addressed debt issues by cancelling all debts, freeing enslaved debtors, and forbidding borrowing on the security of a person.

Overall, Solon's constitutional reforms laid the foundations for Athenian democracy, and their intentions continue to be a subject of historical debate.

French Republic's First Constitution: Revolutionary Ideals and Framework

You may want to see also

The Draconian Constitution

Draco replaced the prevailing system of oral law, which was open to interpretation and modification by Athenian aristocrats, with a written code to be enforced only by a court of law. The laws were inscribed on wooden tablets and displayed on steles shaped like four-sided pyramids, making them accessible to all literate citizens. This was significant as it addressed the unequal access to legal knowledge between the aristocracy and the general populace.

The laws of the Draconian Constitution were known for their harshness, with death prescribed as the penalty for most offences. It is said that the laws were written in blood instead of ink, and that the adjective "draconian" itself refers to unusually harsh punishment. While most of the laws were later repealed, the homicide laws were retained by the early-6th-century BC Solonian Constitution.

The Art of First Kiss: Defining the Moment

You may want to see also

The Areopagite Constitution

According to Aristotle, the Areopagites distributed money to the public as the citizen body prepared to abandon Athens due to the advancing Persian army. The dominant political figure during this period was Cimon, the son of the famous Miltiades and a hero of the Greco-Persian Wars. Cimon won popularity by opening his lands to the public and hosting lavish dinners at his home. He also pursued an aggressive policy against Persia while working to secure peace between Sparta and Athens.

The Athenian Constitution consists of two parts. The first part, from Chapter 1 to Chapter 41, deals with the different forms of the constitution, from the trial of the Alcmaeonidae to the restoration of democracy in 403 BC. Based on references to specific events in the text, scholars have concluded that the Athenian Constitution was written no earlier than 328 BC and no later than 322 BC.

The First Constitution: Flaws and All

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Cleisthenes' political reforms

Athenian leader Cleisthenes, born around 570 BC, is credited with implementing Athens' first constitution and is considered the "true founding father of Athenian democracy".

Cleisthenes' new system of political organisation replaced the previous classification based on four Ionian tribes, which were determined by family relations and formed the basis of the upper-class Athenian power network. By reorganising citizens according to their area of residence (deme) rather than family ties, Cleisthenes aimed to prevent the strife between traditional clans that had led to tyranny in the past. This new democratic power structure also served to weaken his political adversaries.

Another important aspect of Cleisthenes' reforms was the establishment of equal rights for all citizens, or "isonomia". While only free men were considered citizens and held political power, women and foreigners were also granted certain rights and protections. For example, women were allowed to practice religion, and foreign residents may have been granted legal privileges. Additionally, Cleisthenes abolished patronymics in favour of demonymics, increasing Athenians' sense of belonging to their local deme.

Through these reforms, Cleisthenes increased the influence of ordinary citizens in everyday politics and laid the foundation for the development of a fully democratic system of government in Athens.

The Birthplace of Democracy: Where Constitutions Began

You may want to see also

Aristotle's treatise on the Athenian Constitution

The treatise consists of two parts. The first part, from Chapter 1 to Chapter 41, traces the different forms of the constitution from the trial of the Alcmaeonidae to the restoration of democracy in 403 BC. Aristotle provides internal evidence of the timeframe of his writing; in Chapter 54, he mentions the Festival of Hephaestus, which took place in 329 BC, and in Chapter 62, he notes that Athens was sending officials to Samos, something that stopped after 322 BC. This leads scholars to conclude that the treatise was written between 328 and 322 BC.

The second part of the treatise describes the democratic reforms that made the constitution more inclusive. Aristotle writes about the law of ostracism, which was enacted as a safeguard against powerful individuals taking advantage of their positions. He also mentions the institution of Demarchs, who had similar duties to the previous Naucrari, and the naming of the demes, or administrative subdivisions, based on localities or founders. These reforms aimed to create a more democratic system by broadening the government's structure beyond the aristocracy.

The Athenian Constitution is one of 158 constitutions of Greek and non-Greek states that Aristotle compiled. It is the only one to survive intact, and modern scholars debate the extent of Aristotle's personal authorship, as he likely had assistance from his students. The treatise is a valuable source of information on the ancient Athenian political system, and its discovery has been hailed as a significant contribution to Greek historical study.

The Constitution's First Phrase: A Nation's Founding Principles

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The first Athenian leader to write Athens' constitution was Draco, who replaced the prevailing system of oral law with a written code to be enforced only by a court of law in 621 BC.

The constitution written by Draco was known as the Draconian Constitution.

No, the Draconian Constitution was largely harsh and restrictive, with nearly all of its laws later being repealed. The world's first democracy was established in Athens by Cleisthenes in 507 BC.