The First Amendment to the US Constitution, adopted on December 15, 1791, protects freedom of speech and freedom of the press. While the media plays a crucial role in democracies, its independence and impartiality are often challenged. The US Constitution, for instance, does not explicitly mention the media, but it grants Congress the power to regulate it. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) oversees broadcast media, while print media is generally exempt from direct regulation due to its nature as a purchased commodity. The First Amendment protects against government interference, but private interests can still restrict press freedom. The Supreme Court has ruled on several occasions that the Free Speech and Free Press Clauses protect both institutional and non-institutional media.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Freedom of the press | The First Amendment protects freedom of the press and freedom of speech |

| Freedom of speech | The First Amendment protects freedom of the press and freedom of speech |

| Regulation of the media | The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) oversees radio and television communication, and enforces ownership limits to avoid monopolies |

| Media shield laws | The Free Speech and Free Press Clauses protect bloggers and social media users |

| Media cooperation and consolidation | The Sherman Antitrust Act applies to the media |

| Media independence | The media are independent participants in the U.S. political system, but their liberties are not absolute |

| Media impartiality | Broadcasters must provide equal time to persons attacked and to points of view different from those expressed on air |

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

What You'll Learn

Freedom of the press

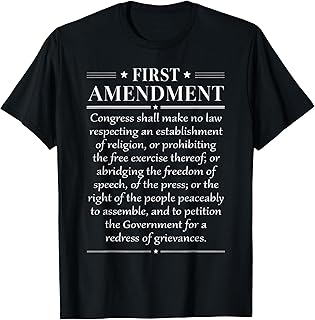

The First Amendment to the US Constitution, adopted on December 15, 1791, explicitly guarantees freedom of the press:

> Congress shall make no law [...] abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press [...]

The First Amendment permits information, ideas and opinions without interference, constraint or prosecution by the government. However, the media's freedom to publish and broadcast is not absolute and does not sanction repression of that freedom by private interests. For example, the First Amendment does not prevent newspapers and other communications businesses from being subject to nondiscriminatory taxation or antitrust laws.

The US Supreme Court has upheld the freedom of the press in several cases. In Near v. Minnesota (1931), the Court rejected prior restraints on publication, a principle that was subsequently applied to free speech more generally. In Associated Press v. United States (1945), the Court held that the Associated Press had violated the Sherman Antitrust Act by prohibiting the sale or proliferation of news to non-member organisations. In Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo (1974), the Court ruled that a state may not require a privately owned company to include views with which it disagrees in its materials. In Cohen v. Cowles Media Co. (1991), the Court found a newspaper in breach of a promise of confidentiality.

Despite these protections, concerns have been raised about the health of the media sector in the US. A 2022 Pew Research survey found that 57% of US journalists were extremely or very concerned about the prospect of press restrictions being imposed in the country.

The Earliest Paleolithic Art: Ancient Creative Expressions

You may want to see also

Media shield laws

The First Amendment, adopted on December 15, 1791, permits information, ideas, and opinions without interference, constraint, or prosecution by the government. The First Amendment also protects the professional activities of journalists. However, it does not grant them immunity from grand jury subpoenas seeking information relevant to a criminal or civil investigation.

Shield laws in the United States are designed to protect reporters' privilege or to prevent prosecution when states' laws differ. A shield law is a law that gives reporters protection against being forced to disclose confidential information or sources in state court. There is no federal shield law, and state shield laws vary in scope. In general, a shield law aims to protect a reporter from being forced to reveal their sources.

As of 2018, 49 states and the District of Columbia offer some form of protection, with 40 states (plus D.C.) having passed shield laws. Some protections apply to civil but not criminal proceedings, while others protect journalists from revealing confidential sources but not other information. Many states have also established court precedents that provide protection to journalists, usually based on constitutional arguments. Only Wyoming lacks both legislation and judicial precedent to protect reporter's privilege.

In recent years, there have been bills for federal shield laws in the United States Congress, including the Free Flow of Information Act, authored by U.S. Senators Charles Schumer and Lindsey Graham. However, none of these bills have passed the Senate due to concerns about leaks of classified information, especially in the modern era of the Internet and non-traditional media outlets.

The courts are currently struggling to define the standards for when shield laws should apply to non-traditional media outlets, such as blogs and Internet publishing.

The Supreme Court: Is It in the Constitution?

You may want to see also

Regulation of media outlets

The First Amendment to the US Constitution, adopted on December 15, 1791, protects freedom of speech and freedom of the press. This amendment permits information, ideas and opinions to be expressed without interference, constraint or prosecution by the government. However, the media's freedom to publish and broadcast is not absolute, and there are rules and regulations that media outlets must follow.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) was created by the Communications Act of 1934 and is responsible for licensing and monitoring radio and television stations. The FCC enforces rules about limiting advertising, providing a public forum for discussion, and serving local and minority communities. It also enforces ownership limits to avoid monopolies and can censor materials deemed inappropriate. The FCC has the power to revoke licenses from broadcast stations and has done so in cases involving indecency and equal time violations.

The Supreme Court has ruled that generally applicable laws do not violate the First Amendment, even if they incidentally affect the press. However, laws that specifically target the press or treat different media outlets differently may violate the First Amendment. For example, in Grosjean v. Am. Press Co. (1936), the Supreme Court held that a tax exclusively on newspapers violated the freedom of the press. In another case, Miami Herald Pub. Co. v. Tornillo (1974), the Court held that a state could not require a privately owned utility company to include views it disagreed with in its billing envelopes.

In addition to legal regulations, media outlets are also subject to market forces that can influence their content and operations. The growth of social media and the advertising model have incentivized "clickbait" headlines, while falling circulations have led to cuts in newspaper staffing and local news outlets. These changes in the media market have weakened some forms of reporting, particularly investigative journalism.

While the First Amendment protects freedom of speech and the press, it does not grant media outlets special immunity from general laws. For example, in Associated Press v. NLRB (1937), the Supreme Court held that the National Labor Relations Act could be applied to a newsgathering agency without raising constitutional problems. Media outlets are also subject to taxation and employment laws, such as wage and hour standards.

US-Mexico Treaty: A Constitutional Alliance

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

Media cooperation and consolidation

The First Amendment of the US Constitution, adopted on December 15, 1791, permits information, ideas, and opinions without interference, constraint, or prosecution by the government. This includes freedom of the press, which is further supported by the Free Speech and Free Press Clauses. These clauses do not differentiate between media businesses and non-professional speakers, protecting bloggers and social media users.

The US Supreme Court has historically supported these freedoms, refusing to grant increased First Amendment protection to institutional media over other speakers. For example, in a case involving campaign finance laws, the court rejected the notion that communication by the institutional press is entitled to greater constitutional protection than the same communication by non-institutional-press businesses.

Despite these protections, critics argue that media deregulation and the resulting consolidation of ownership threaten the diversity and quality of information provided to the public. This concentration of ownership refers to the control of news sources by fewer and fewer corporations, reducing the number of media options available and potentially leading to corporate censorship.

Historically, the US government has made efforts to preserve media diversity and prevent consolidation. For instance, in 1945, Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black blocked a merger between the Associated Press and other newspaper publishing companies, stating that:

> The First Amendment ... rests on the assumption that the widest possible dissemination of information from diverse and antagonistic sources is essential to the welfare of the public ...

However, in the 1980s, a shift towards deregulation occurred, and efforts to prevent media consolidation began to unravel. This trend has continued, with Trump's FCC, for example, relaxing rules and allowing for further media consolidation.

While critics worry about the negative impacts of consolidation, such as reduced diversity and quality of information, others argue that higher levels of consolidation can lead to more efficient allocation of resources and economies of scale, potentially benefiting news quality.

Who Were the Key Authors of the Constitution?

You may want to see also

Media independence

The First Amendment to the US Constitution, adopted on December 15, 1791, permits the free flow of information, ideas, and opinions without interference, constraint, or prosecution by the government. It states that "Congress shall make no law [...] abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press". The First Amendment does not, however, grant media the privilege of special access to information or locations, such as prisons.

The interpretation of media independence varies depending on the context. For example, in discussions about the role of media within authoritarian societies, the relevance of European public service broadcasters, or the "alternative press", the concept of independence takes on different nuances.

In practice, media independence can be impacted by political and economic influences, as well as regulatory authorities. To ensure media independence, regulatory authorities should ideally be placed outside of governments' directives, with transparent and fair procedures for issuing licenses to broadcasters.

Research has shown that independent media plays a crucial role in improving government accountability and reducing corruption. However, it is important to note that private media, while functioning outside of direct government control, can still be influenced by advertising support, which may be used as a political tool by larger advertisers, including governments.

Carolina's Constitution: Laying the Foundation for a Colony

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The First Amendment protects the freedom of the press, allowing for the dissemination of information, ideas and opinions without interference, constraint or prosecution by the government.

Yes, the media does not have the right to commit slander, speak or print false information with the intent to harm a person or entity.

The FCC is a government entity that oversees radio, television and telephone communication. It requires radio and television stations to apply for licenses, which are granted if stations follow rules about limiting advertising, providing a public forum for discussion, and serving local and minority communities.

Yes, under the First Amendment, it is unclear whether civil or criminal actions for "invasion of privacy" are allowed. However, the Supreme Court has upheld the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, which impose restrictions and penalties on the press for publishing certain types of statements or information.

Yes, bloggers and social media users are protected by the Free Speech and Free Press Clauses, which do not differentiate between media businesses and nonprofessional speakers.

![The First Amendment: [Connected Ebook] (Aspen Casebook) (Aspen Casebook Series)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61p49hyM5WL._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![First Amendment: [Connected eBook] (Aspen Casebook Series)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61-dx1w7X0L._AC_UL320_.jpg)