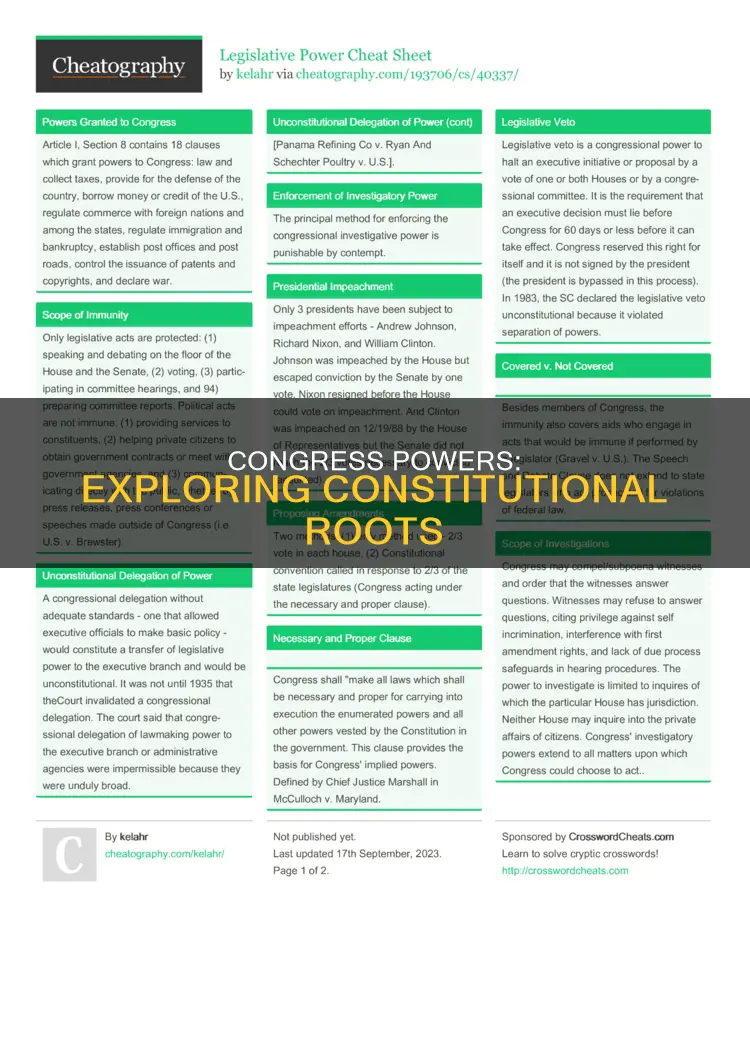

The United States Congress derives its powers from the United States Constitution, particularly Article I, which outlines the legislative branch's powers, and Article V, which grants Congress the ability to propose and send Constitutional amendments to the states for ratification. Congress has exclusive authority over financial and budgetary matters, and its powers include the ability to lay and collect taxes, borrow money, regulate commerce, coin money, establish post offices, protect patents and copyrights, establish lower courts, declare war, and raise and support an Army and Navy. Congress also has implied powers derived from clauses such as the General Welfare Clause, the Necessary and Proper Clause, and the Commerce Clause.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The power to lay and collect taxes

The Taxing Clause was established to address the shortcomings of the Articles of Confederation, which did not grant the national government the power to tax individuals directly, leaving it unable to raise funds effectively. The Framers of the Constitution decided that Congress must have the power to "lay and collect taxes", and this power was not limited to repaying Revolutionary War debts but was also intended to be prospective.

The specific wording of the Taxing Clause is fairly general, leaving it open to interpretation by the Supreme Court. While Congress has broad authority to decide what will be taxed and how much, there are some limitations to its taxing power. For example, the Free Speech Clause prevents Congress from taxing individuals for criticising the federal government. Additionally, the Supreme Court has ruled that Congress may not lay a tax that impairs the sovereignty of the states.

The Supreme Court has also weighed in on the scope of the federal taxing and spending powers, siding with Hamilton's view that Congress possesses a robust power to tax and spend, regardless of whether it can be tied to another enumerated power of Congress. This decision in United States v. Butler (1936) established that the Taxing Clause gives Congress independent power.

The Court has also clarified that Congress can use its taxing power to carry out regulatory measures that might be impermissible under its other powers. For example, in NFIB v. Sebelius (2012), the Court upheld the constitutionality of a provision in the Affordable Care Act requiring individuals to purchase minimum health insurance or pay a penalty. The Court ruled that this was a valid use of Congress's taxing authority, even if the primary purpose was to regulate behaviour rather than raise revenue.

Compromises in the Constitution: Political Deals and Their Legacy

You may want to see also

The power to regulate commerce

The Commerce Clause, outlined in Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3 of the US Constitution, grants Congress the power to "regulate commerce with foreign nations, among states, and with the Indian tribes". This clause has been used by Congress to justify exercising legislative power over the activities of states and their citizens, often leading to controversy regarding the balance of power between federal and state governments.

The interpretation of the Commerce Clause has been a subject of debate, with the Constitution not explicitly defining the word "commerce". Some argue that it refers simply to trade or exchange, while others claim that it describes broader commercial and social intercourse between citizens of different states. The Supreme Court has also provided interpretations, with early cases primarily viewing the clause as limiting state power rather than a source of federal power.

During the 1930s, the Supreme Court increasingly heard cases on Congress's power to regulate commerce, resulting in an evolution of its jurisprudence on the interstate Commerce Clause during the twentieth century. In NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp (1937), the Court recognized broader grounds for using the Commerce Clause to regulate state activity, stating that an activity was considered commerce if it had a "substantial economic effect" on interstate commerce or if the "cumulative effect" of one act could impact such commerce.

In United States v. Lopez (1995), the Supreme Court attempted to curtail Congress's broad legislative mandate under the Commerce Clause by adopting a more conservative interpretation. The Court held that Congress only has the power to regulate the channels of commerce, the instrumentalities of commerce, and actions that substantially affect interstate commerce.

Despite this, subsequent cases such as Gonzales v. Raich and NFIB v. Sebelius (2012) demonstrated a continued willingness by the Court to interpret the Commerce Clause liberally in certain contexts. The Commerce Clause has been a significant factor in shaping the balance of power between the federal government and the states, influencing policies related to trade, economic activities, and social issues.

Key Constitutional Agreements: What Made the Cut

You may want to see also

The power to declare war

The Declare War Clause is a central element of Congress's war powers and gives Congress broad authority to pursue the war effort. According to the Supreme Court, the power to declare war includes the power to prosecute it by all means and in any manner in which war may be legitimately prosecuted. Congress has enacted statutes that trigger special wartime authorities concerning the military, foreign trade, energy, communications, and alien enemies when it declares war.

The Framers of the Constitution intended to improve the United States' ability to ensure its peace and security through military protection. The Declare War Clause was also included to limit the president's power to initiate wars. In the early years of the US, Congress's approval was thought to be necessary for any significant use of force. For example, Congress issued a formal declaration of war for the War of 1812 and approved lesser uses of force, such as conflicts with Native American tribes.

However, in modern times, presidents have increasingly used military force without formal declarations or express consent from Congress. For example, President Truman ordered troops into the Korean War, which he called a "police action", and the Vietnam War lasted over a decade without a declaration of war. By 1970, it was calculated that US presidents had ordered troops into action without congressional approval 149 times. This has led to criticism that Congress has failed to adequately oversee the executive branch and that the executive branch has usurped Congress's power to declare war.

British Constitution: Exploring Its Sources and Nature

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The power to raise and support an army

The Constitution grants Congress the power to raise and support an army. This power is derived from Article I, which focuses on Congress and its role in government. It is further supported by the Necessary and Proper Clause, which empowers Congress to pass laws necessary for executing the federal government's powers.

Throughout history, there have been debates and conflicts regarding the scope of Congress's power to raise and support an army, especially in relation to the president's war powers. The Supreme Court has played a significant role in interpreting and upholding Congress's authority in this area. For example, in the Selective Draft Law Cases of 1918, the Court upheld the constitutionality of compulsory military service, rejecting arguments that it violated the Thirteenth Amendment.

Congress's power to raise and support an army includes the ability to establish the military chain of command, assign duties to officers, and regulate the armed forces. They are responsible for funding the military and approving the military budget, although the president can veto this budget. Additionally, Congress has the power to declare war, which is a critical aspect of their authority over the military.

In summary, the power to raise and support an army is a significant responsibility granted to Congress by the Constitution. It serves as a check on the president's powers and ensures that the decision to go to war is not made by a single person but rather with the approval of Congress, representing the people.

Your Rights: Phone Calls When Arrested

You may want to see also

The power to admit new states into the Union

The powers of the United States Congress are implemented by the United States Constitution, with certain powers explicitly defined and called "enumerated powers". One such enumerated power is the ability to admit new states into the Union. This power is granted by Article IV, Section 3 of the Constitution, also known as the Admissions Clause or the New States Clause.

The Admissions Clause gives Congress the authority to admit new states into the Union, beyond the original thirteen states that existed when the Constitution came into effect on June 21, 1788. Since then, 37 states have been admitted to the Union, all but six of which were established within existing U.S. organized incorporated territories. The Admission Clause also grants Congress the power to "dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States".

The process of admitting new states often involves the use of an enabling act, which authorizes the people of a territory or region to draft a proposed state constitution as a step towards admission to the Union. This has been a common historical practice, although several states have been admitted without an enabling act. The broad outline for the process was established by the Land Ordinance of 1784 and the 1787 Northwest Ordinance, which predates the U.S. constitution.

The Admissions Clause contains two main limitations on congressional power to admit new states. The first is that no new state shall be formed within the jurisdiction of an existing state without the consent of the affected state legislatures and Congress. This caveat was intended to give certain states with western land claims a veto over whether their western counties could become states. The second limitation, known as the equal footing doctrine, requires that all new states be admitted on equal terms with the original states, with all the powers of sovereignty and jurisdiction. This principle was formalized in the acts of admission for subsequent states after Vermont and Kentucky were admitted on equal terms with the existing 13 states in 1791 and 1792, respectively.

Some have proposed admitting new states for the purpose of amending the Constitution to ensure equal representation. For example, admitting Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico as states could make it easier to pass new amendments. Additionally, Congress could delineate the borders of new states and provide for elections for new congressional delegations, as was done when West Virginia became a state in 1861.

Exploring the Relevance of Our Constitution Today

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Congress's powers are implemented by the United States Constitution, rulings of the Supreme Court, and by its own efforts, and other factors such as history and custom.

Article I of the Constitution sets forth most of the powers of Congress, which include numerous explicit powers enumerated in Section 8. These include the power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises, to pay debts, borrow money, regulate commerce, coin money, establish post offices, protect patents and copyrights, establish lower courts, declare war, and raise and support an Army and Navy.

Congress has implied powers derived from clauses such as the General Welfare Clause, the Necessary and Proper Clause, and the Commerce Clause, and from its legislative powers. Congress has exclusive authority over financial and budgetary matters.

In Helvering v. Davis, the Supreme Court affirmed Social Security as an exercise of the power of Congress to spend for the general welfare. In McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), the Supreme Court ruled that under the Necessary and Proper Clause, Congress had the power to establish a national bank to carry out its powers to collect taxes, pay debts, and borrow money.

Some critics have charged that Congress has, in some instances, failed to adequately oversee the other branches of government. Congress has also been criticised for being lax in its oversight duties regarding presidential actions such as warrantless wiretapping. Although the Constitution gives Congress the power to declare war, some critics charge that the executive branch has usurped this task.