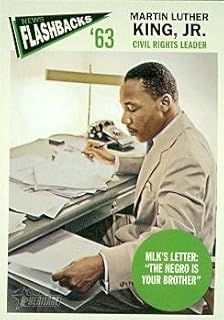

Martin Luther King Jr. was born in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1929. During his sophomore year at Morehouse, he wrote a letter to the editor of the Atlanta Constitution, the city's largest newspaper. The letter, titled Kick Up Dust, was published on August 6, 1946, and responded to the paper's reporting on the killing of Macio Snipes, the only Black person to vote in his district in Taylor County, Georgia. The Atlanta Constitution was first published in 1868 and has played a significant role in the history of Atlanta and Georgia. It has also been a platform for notable figures like Margaret Mitchell and Ralph McGill, who was a supporter of the American Civil Rights Movement. The paper has won several Pulitzer Prizes and, in 2001, merged with The Atlanta Journal to become The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name of the letter | "Kick Up Dust" |

| Date of publication | 6 August 1946 |

| Publication | Atlanta Constitution |

| Location | Atlanta, Georgia |

| Type of publication | Newspaper |

| Frequency | Daily |

| Year of first publication | 1868 |

| Month and day of first publication | June 16 |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Martin Luther King Jr.'s 'Kick Up Dust' letter

On 26 July 1946, the Atlanta Constitution reported the racially-motivated killing of Macio Snipes, a Black World War II veteran and the only Black person to vote in his district in Taylor County, Georgia. The day after he voted, Snipes was shot and killed by four white men. The following day, on 27 July, the same newspaper reported that twenty white men shot two Black couples driving near Monroe, Georgia. The Atlanta Constitution expressed "a heartfelt sense of shame and embarrassment" over these incidents. However, the newspaper reiterated its opposition to federal intervention in such cases of mob violence.

Martin Luther King Jr., then a sophomore at Morehouse College, was moved to write a letter to the editor of Atlanta's largest newspaper, the Atlanta Constitution, in response to these killings. In his letter, titled "Kick Up Dust," King criticised those who attempted to "obscure the real question of rights and opportunities" by raising "the scarecrow of social mingling and intermarriage." King's letter was likely a response to the racially motivated murders reported by the Atlanta Constitution, as well as the newspaper's stance on federal legislation regarding mob violence.

The Atlanta Constitution, first published in 1868 as the Atlanta Daily Opinion, was a prominent newspaper in Atlanta, Georgia. Over the years, it underwent several name changes and ownership transfers. The paper was known for its coverage of Georgia and the neighbouring states, and it played a role in the American Civil Rights Movement. One of its editors in the 1940s, Ralph McGill, was a supporter of the movement.

Martin Luther King Jr.'s "Kick Up Dust" letter is a significant piece of history, offering insight into the early development of his civil rights activism. King, who grew up in Georgia, would go on to become a world-famous Baptist minister and civil rights leader. He played a pivotal role in the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott and the 1963 Birmingham Campaign, and his "I Have a Dream" speech delivered in Washington, D.C., in August 1963, is considered a landmark moment in the Civil Rights Movement.

Constitutional Crisis: Technical Error's Impact

You may want to see also

The Atlanta Constitution's history

The Atlanta Constitution, formerly known as The Constitution, was first published on June 16, 1868. Carey Wentworth Styles, James Anderson, and William Hemphill purchased a small newspaper called the Atlanta Daily Opinion and renamed it The Constitution. The name was chosen because Atlanta was under martial law during the Reconstruction era, and the founders advocated for a return to the constitutional government that existed before the Civil War. The paper's name changed to The Atlanta Constitution in October 1869.

The Atlanta Constitution was one of the leading journalistic voices in the country. Ralph McGill, editor of the paper in the 1940s, was one of the few southern newspaper editors to support the American Civil Rights Movement. McGill received threatening letters as he established himself as "The Conscience of the South." He went on to become the publisher of the newspaper, and Eugene Patterson succeeded him as editor. In 1950, the Constitution established a radio station, WCON (AM 550), and later received approval to operate an FM station and a TV station.

The Atlanta Constitution was Atlanta's largest newspaper. In 1946, Martin Luther King Jr. wrote a letter to the editor of the paper, titled "Kick Up Dust." In this letter, King expressed his political and social views, including his support for civil rights and opposition to racial violence. The Atlanta Constitution reported on several incidents of racial violence during this time, expressing shame and embarrassment while maintaining its opposition to federal involvement in addressing mob violence.

In 1950, Cox Enterprises bought the Constitution, and in 1982, the newsrooms of the Constitution and the Atlanta Journal were combined, although they continued to publish separate editions. In 2001, the two papers merged to produce one daily morning paper, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution has won several Pulitzer Prizes over the years, including for editorial cartooning and commentary.

American Constitution: Religious Roots and Influence

You may want to see also

The Atlanta Constitution's stance on racial equality

The Atlanta Constitution, originally named The Constitution, was first published in 1868. The newspaper was founded by Carey Wentworth Styles, James Anderson, and William Hemphill. While The Atlanta Constitution was Atlanta's largest newspaper, its stance on racial equality was complex and evolved over time.

In the late 1940s, Ralph McGill, editor of The Atlanta Constitution, was one of the few southern newspaper editors to support the American Civil Rights Movement. This suggests that the newspaper may have had a progressive stance on racial equality during this period. Indeed, on July 26, 1946, The Atlanta Constitution reported the killing of Macio Snipes, the only Black person to vote in his district in Taylor County, Georgia. The newspaper expressed "a heartfelt sense of shame and embarrassment" over the incident. However, it is important to note that The Atlanta Constitution also repeated its opposition to "legislation that would make instances of mob violence a matter for Federal authorities."

During the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, The Atlanta Constitution played a significant role in covering the struggle for racial equality. Atlanta itself was a major organizing center of the movement, with Martin Luther King Jr. and students from Atlanta's historically Black colleges and universities at the forefront. The newspaper reported on various incidents of racial violence, such as the bombing of a Reform Jewish temple on Peachtree Street in 1958.

The Atlanta Constitution also gave a platform to voices advocating for racial equality. For example, on March 9, 1960, the newspaper published "An Appeal for Human Rights," a declaration of solidarity with the student sit-in movement and Atlanta's African American community. The student-led coalition successfully pressured Atlanta's political and business leaders to end segregation in public facilities, which advanced the goal of social equality and had a significant impact on the region's economy.

However, it is important to acknowledge that Atlanta and the surrounding region had a long history of racial segregation and discrimination. A 2015 study found that Atlanta was the second most segregated city in the United States and the most segregated in the South. This segregation was evident in various aspects of life, including residences, schools, neighborhoods, transportation, and political representation. While The Atlanta Constitution may have played a role in exposing these issues and advocating for change, the newspaper's overall stance on racial equality was likely shaped by the complex and often contradictory social and political landscape of the time.

Income Taxes: Legitimizing the Constitution

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The Atlanta Constitution's radio and TV stations

The Atlanta Constitution established one of the first radio broadcasting stations, WGM, which began operating on March 17, 1922. However, WGM ceased operations after just over a year. The equipment was then donated to what was then known as the Georgia School of Technology, which used it to help launch WBBF (later WGST, now WGKA AM 920) in January 1924.

In late 1947, The Constitution established another radio station, WCON (AM 550). Subsequently, it received approval to operate an FM station, WCON-FM 98.5 mHz, and a TV station, WCON-TV, on channel 2. However, due to the 1950 merger with the Journal, WCON and the original WSB-FM were shut down to comply with contemporary Federal Communications Commission (FCC) "duopoly" regulations that disallowed owning more than one AM, FM, or TV station in a given market. The WCON-TV construction permit was canceled, and WSB-TV was allowed to move from channel 8 to channel 2.

Before the merger, both papers planned to start their own TV stations: WSB-TV on channel 8 for the Journal, and WCON-TV on channel 2 for The Constitution. Only WSB got on the air, beginning in 1948 as the first TV station in the Deep South.

Abolitionists' Constitutional Battle: Freedom's Legal Fight

You may want to see also

The Atlanta Constitution's notable editors

The Atlanta Constitution has had many notable editors over the years, with the newspaper first being published on June 16, 1868, by Carey Wentworth Styles and James H. Anderson, who renamed a small newspaper, the Atlanta Daily Opinion, to The Constitution. Styles was the first editor and used the newspaper's pages to editorialise against Radical Reconstruction and the Rufus Bullock administration. However, after six months, Styles could no longer finance his half of the newspaper, and his shares were transferred to Anderson, who then sold them to William Arnold Hemphill, the paper's business manager and Anderson's son-in-law.

In 1870, Anderson sold his one-half interest in the paper to Col. E. Y. Clarke, who, along with N. P. T. Finch, managed the editorial department. Clarke sold his interest in the paper to Evan P. Howell in 1876, who subsequently became company president. Henry Grady, who joined the newspaper in 1876, brought a new approach to its journalism, providing readers with stories from around the country and writing about the South for northern newspapers. Grady was progressive and the first to position the newspaper as one of national scope and reputation. He was editor-in-chief during the 1880s and was a spokesman for the "New South", encouraging industrial development and the founding of Georgia Tech in Atlanta. Grady was also a member of the "Atlanta Ring" of Democratic political leaders and used his influence to promote the New South.

Clark Howell, Evan P. Howell's brother, became company president in 1902, a position he held until 1912 when Albert Howell, another brother, took over. Clark Howell remained an editor and owner of the newspaper until his death in 1936, at which point Clark Howell Jr took over. Ralph McGill, who joined the newspaper in 1929, was editor in the 1940s and was one of the few southern newspaper editors to support the American Civil Rights Movement. He was a strong supporter of the movement and continued reporting on social injustices despite harsh opposition. He was also the first editor of the newspaper to win a Pulitzer Prize.

Other noteworthy editors of The Atlanta Constitution include J. Reginald Murphy, who gained notoriety after being kidnapped in 1974, Celestine Sibley, an award-winning reporter, editor and beloved columnist, and Lewis Grizzard, a popular humour columnist. Julia Wallace became the first female editor of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2002.

The Constitution: God and Bible Mention

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

MLK Jr. published his letter in The Atlanta Constitution, Atlanta's largest newspaper.

MLK Jr.'s letter was titled "Kick Up Dust".

The letter was published on August 6, 1946.

The letter was a response to the Atlanta Constitution's coverage of the killing of Macio Snipes, the only Black person to vote in his district in Taylor County, Georgia.