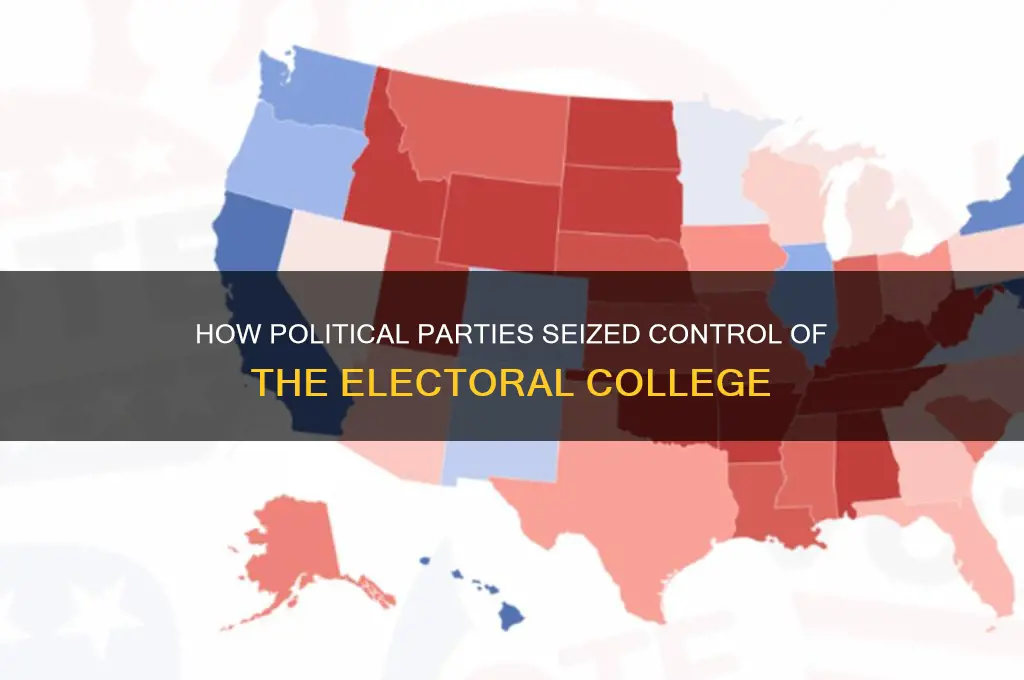

The question of when political parties gained control of the Electoral College is rooted in the early development of the United States' political system. Initially, the Electoral College, established by the Constitution in 1787, was designed to operate independently of political factions, with electors expected to act as impartial representatives of the people. However, the emergence of political parties in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, particularly the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties, fundamentally altered this dynamic. By the 1820s and 1830s, political parties had firmly established mechanisms to influence and control the selection of electors, effectively transforming the Electoral College into an extension of partisan politics. This shift was solidified through party-controlled state legislatures and later through popular elections for electors, ensuring that the Electoral College became a tool for party dominance in presidential elections.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Emergence of Political Parties | Early 1790s, with the formation of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties. |

| First Party Control of Electoral College | 1796, when John Adams (Federalist) won the presidency through the Electoral College. |

| Solidification of Party Influence | Early 19th century, as parties began to organize electors and control state legislatures. |

| Modern Party Dominance | Post-Civil War era, with the Republican and Democratic parties becoming the dominant forces. |

| Current Party Control Dynamics | Since the late 19th century, the Electoral College has been primarily controlled by the two major parties, with occasional third-party challenges. |

| Key Turning Points | 1824 (Corrupt Bargain), 1860 (Republican rise), and 1968 (modern two-party system reinforcement). |

| State-Level Party Influence | Parties control the selection of electors in most states, ensuring party loyalty. |

| Role of Party Conventions | Parties nominate candidates who then compete in the Electoral College system. |

| Impact of Party Polarization | Increased polarization has strengthened party control over electors and state-level politics. |

| Recent Trends | Continued dominance of Democrats and Republicans, with no third party gaining significant Electoral College influence since the 1960s. |

Explore related products

$13.55 $21.95

$18.99 $18.99

What You'll Learn

Early Republic Era: Emergence of Parties

The Electoral College, designed to be a deliberative body of independent electors, quickly became a tool for emerging political parties in the Early Republic Era. By the 1790s, the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties began strategizing to influence electors, marking the beginning of party control over the system. This shift was not immediate but evolved through elections, as parties realized the importance of coordinating electors to secure presidential victories.

Consider the 1796 election, the first true partisan contest. Federalists and Democratic-Republicans campaigned vigorously, each aiming to win a majority of electors for their candidate. While the Electoral College still nominally consisted of independent electors, party loyalty increasingly dictated their votes. John Adams’ narrow victory over Thomas Jefferson highlighted how parties were already manipulating the system, even if electors retained theoretical independence. This election demonstrated the growing tension between the Electoral College’s original design and the practical realities of party politics.

To understand this transformation, examine the mechanics of early party strategy. Parties began nominating slates of electors loyal to their cause, effectively bypassing the College’s intended role as a nonpartisan body. By 1800, this trend culminated in the infamous tie between Jefferson and Aaron Burr, exposing the flaws of a system now dominated by parties. The 12th Amendment, ratified in 1804, was a direct response to this crisis, formalizing the role of parties by separating votes for president and vice president. This amendment underscored the irreversible shift toward party control of the Electoral College.

Practical takeaways from this era are clear: parties adapted quickly to exploit the Electoral College’s weaknesses, turning it into a mechanism for partisan competition. For modern observers, this history serves as a cautionary tale about unintended consequences. The founders’ vision of independent electors was no match for the organizing power of political parties. By the early 1800s, the Electoral College had become a partisan battleground, a transformation that continues to shape American elections today.

Exploring Power, Culture, and Society: The Importance of Political Anthropology

You may want to see also

1824 Election: Decisive Party Influence

The 1824 presidential election marked a turning point in American political history, as it showcased the growing power of political parties in shaping the outcome of the Electoral College. This election, often referred to as the "Election of the People's Choice," was the first in which no candidate secured a majority of electoral votes, throwing the decision to the House of Representatives. The contest between John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, William Crawford, and Henry Clay revealed the intricate dynamics of party influence and the emergence of a new era in American politics.

The Rise of Factions and Party Loyalty

By 1824, the Democratic-Republican Party, which had dominated American politics since the early 1800s, had fractured into competing factions. These factions, though not yet fully formed into modern political parties, were aligned behind regional interests and personal loyalties. Andrew Jackson, a war hero and populist figure, garnered widespread support from the West and South, while John Quincy Adams drew strength from the Northeast. William Crawford, the party’s initial favorite, represented the old guard, and Henry Clay appealed to Western interests. This fragmentation highlighted the growing importance of organized support networks, as candidates relied on regional and ideological alliances to secure votes.

The Role of the Electoral College in Party Politics

The 1824 election demonstrated how political parties began to manipulate the Electoral College to their advantage. Each candidate’s supporters strategically campaigned in states where they had the strongest base, aiming to maximize their electoral vote count. For instance, Jackson’s supporters focused on states with populist sentiment, while Adams’ backers targeted New England. This election was the first in which the Electoral College became a battleground for party influence rather than a mere reflection of individual state preferences. The lack of a majority winner underscored the need for parties to coordinate their efforts more effectively in future elections.

The Corrupt Bargain and Its Aftermath

The election’s outcome was decided in the House of Representatives, where Henry Clay, as Speaker of the House and a candidate himself, threw his support behind John Quincy Adams. This decision, known as the "Corrupt Bargain," was widely seen as a backroom deal, as Adams subsequently appointed Clay as Secretary of State. The controversy fueled Andrew Jackson’s supporters, who felt their candidate had been robbed despite winning the popular and electoral vote pluralities. This event solidified the importance of party unity and strategic alliances, as Jackson’s backers regrouped to form the Democratic Party, while Adams’ supporters became the nucleus of the Whig Party.

Takeaway: A Watershed Moment for Party Control

The 1824 election was a decisive moment in the evolution of political parties’ control over the Electoral College. It revealed the limitations of a system designed for independent-minded electors and the growing necessity of party organization to navigate its complexities. The election’s aftermath accelerated the transformation of American politics from a system of personal rivalries to one dominated by disciplined, ideologically driven parties. By demonstrating the power of party influence, the 1824 election set the stage for the modern two-party system and the strategic use of the Electoral College as a tool for political dominance.

Securing Political Party Funding: Strategies for Success in Campaign Finance

You may want to see also

Post-Civil War: Solidified Party Dominance

The post-Civil War era marked a pivotal shift in American politics, as political parties solidified their dominance over the Electoral College. By the late 19th century, the Republican and Democratic parties had established a duopoly, effectively controlling the nomination and election processes. This period saw the rise of party machines, which mobilized voters, managed campaigns, and ensured party loyalty through patronage systems. The 1876 election, often called the "Corrupt Bargain," exemplified this trend, as party leaders negotiated the outcome, cementing their influence over the Electoral College.

Consider the mechanics of this transformation. After the Civil War, state legislatures, increasingly controlled by one of the two major parties, began to dictate how electors were chosen. This shift from a more decentralized system to one dominated by party interests was gradual but profound. For instance, by 1880, nearly all states had adopted the winner-take-all method for allocating electoral votes, a system that favored strong party organization. This change marginalized independent candidates and smaller parties, ensuring that the Electoral College became a tool for party dominance rather than a neutral mechanism for presidential selection.

A persuasive argument can be made that this era laid the groundwork for the modern Electoral College system. The post-Civil War period saw the institutionalization of party control, with conventions, primaries, and caucuses becoming formalized processes. Parties used these structures to vet candidates, raise funds, and coordinate campaigns across states. The 1896 election, where William McKinley’s Republican campaign outspent and outorganized William Jennings Bryan’s Democrats, showcased the power of party machinery. This election demonstrated how parties could leverage resources and organization to secure Electoral College victories, a strategy still employed today.

Comparatively, the post-Civil War era stands in stark contrast to the early years of the republic, when electors often acted independently. By the late 1800s, electors were expected to vote along party lines, their choices predetermined by state-level party organizations. This shift reduced the Electoral College’s role as a deliberative body and transformed it into a rubber stamp for party nominees. The practical takeaway is clear: the post-Civil War period was when political parties gained near-total control over the Electoral College, a dominance that continues to shape American presidential elections.

To understand this era’s impact, examine the long-term consequences. The party-dominated Electoral College system has endured, with only occasional challenges from third-party candidates or faithless electors. This structure has implications for modern elections, as it limits the influence of independent voters and smaller parties. For those seeking to reform the Electoral College, studying this period offers critical insights into how party control was established and maintained. By analyzing the post-Civil War era, we can better navigate contemporary debates about electoral fairness and representation.

The Political Party Behind the Bill of Rights: Uncovering History

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

20th Century: Modern Party Control

The 20th century marked a significant shift in the way political parties exerted control over the Electoral College, transforming it into a system where party loyalty became paramount. By the early 1900s, state legislatures, which had previously selected electors independently, began adopting laws requiring electors to pledge their votes to the party’s presidential nominee. This change was formalized through the widespread adoption of "short ballot" systems, where voters cast a single vote for a party’s presidential candidate rather than individual electors. For instance, by 1932, all states except South Carolina had moved to this system, effectively handing parties direct control over elector selection. This shift streamlined the process but also reduced the autonomy of electors, making the Electoral College a tool for party dominance rather than independent judgment.

Analyzing this trend reveals a strategic move by parties to consolidate power and minimize dissent. The rise of party machines and the need for cohesive national campaigns during this era incentivized parties to ensure electors remained loyal. The 1952 election serves as a case study: when Georgia elector W.F. Turnage attempted to vote against his party’s nominee, he faced legal challenges and public backlash, illustrating the rigid control parties had established. This period also saw the emergence of "faithless elector" laws in many states, further cementing party authority by penalizing electors who deviated from their pledged votes. Such measures underscore how the 20th century became the era of modern party control over the Electoral College.

To understand the practical implications, consider the role of party conventions and primaries in this system. By mid-century, parties had perfected the art of vetting candidates and rallying support through these mechanisms, ensuring that only party-approved nominees reached the general election. This internal party control translated directly into Electoral College dominance, as nominees could rely on a pre-determined bloc of electoral votes. For example, the 1964 election saw Lyndon B. Johnson secure 486 electoral votes, a landslide victory made possible by the Democratic Party’s unified front across states. This example highlights how party control over the Electoral College became a linchpin of modern presidential elections.

A comparative look at earlier centuries reveals the stark contrast. In the 19th century, electors often acted as independent agents, sometimes even swaying elections against party interests. The 1836 election, where Virginia’s electors refused to vote for Martin Van Buren’s vice-presidential nominee, is a prime example. By contrast, the 20th century’s party-controlled system left little room for such deviations. This evolution reflects broader changes in American politics, including the rise of mass media, nationalized campaigns, and the decline of local political machines. Parties adapted by centralizing control, turning the Electoral College into a mechanism for enforcing party discipline rather than reflecting diverse state interests.

In conclusion, the 20th century’s transformation of the Electoral College into a party-controlled institution was both deliberate and profound. Through legislative changes, legal enforcement, and strategic party organization, the system evolved to prioritize party unity over individual elector autonomy. This shift had lasting implications, shaping the dynamics of presidential elections and reinforcing the two-party system’s dominance. While critics argue this reduces the Electoral College’s original intent, proponents view it as a necessary adaptation to modern political realities. Understanding this history is crucial for anyone seeking to navigate or reform the complexities of the Electoral College today.

Switching Political Parties: Navigating Challenges and Personal Convictions

You may want to see also

Contemporary Era: Party Strategies in Elections

Political parties have long sought to influence the Electoral College, but the contemporary era has seen a marked shift in strategies, with data-driven microtargeting and battleground state focus becoming paramount. This evolution is evident in the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections, where both parties allocated resources disproportionately to a handful of swing states like Florida, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. For instance, in 2020, over $1 billion was spent on advertising in these states alone, reflecting their outsized role in determining Electoral College outcomes. This concentration of effort underscores a strategic recalibration, where parties prioritize states with the highest potential to shift electoral votes rather than pursuing a broader national appeal.

To maximize their impact, parties now employ sophisticated data analytics to identify and mobilize specific voter demographics. Democrats, for example, have focused on turning out young voters and minorities, while Republicans have targeted rural and non-college-educated whites. This microtargeting is facilitated by advanced voter databases and social media platforms, allowing campaigns to tailor messages with surgical precision. A notable example is the 2018 midterms, where Democratic groups like the DSCC used data to increase Latino turnout in Nevada, flipping a Senate seat. Such strategies highlight the importance of understanding voter behavior at a granular level to sway Electoral College results.

However, this hyper-focus on swing states has drawbacks, particularly in terms of resource allocation and voter engagement. Non-battleground states often receive minimal attention, leading to lower turnout and a sense of political alienation among their residents. For instance, California and Texas, despite their large populations, are largely ignored due to their predictable partisan leanings. This imbalance raises questions about the fairness of a system where the majority of campaign efforts—and, by extension, policy promises—are directed at a fraction of the electorate. Critics argue that this approach undermines the principle of equal representation and exacerbates regional divides.

To navigate these challenges, parties must balance their Electoral College strategies with broader national outreach. One practical step is investing in down-ballot races in safe states to build long-term infrastructure and engage voters who feel neglected. Additionally, campaigns should leverage digital tools to reach voters in non-competitive states, fostering a sense of inclusion and encouraging participation. For example, virtual town halls and grassroots organizing can help bridge the gap between swing and non-swing states. By adopting such measures, parties can optimize their Electoral College strategies while maintaining a commitment to democratic ideals.

In conclusion, the contemporary era’s party strategies in elections reflect a calculated focus on the Electoral College, driven by data and battleground state priorities. While effective in securing victories, this approach risks alienating large segments of the electorate. Parties must therefore innovate, combining microtargeting with inclusive outreach to ensure that their strategies strengthen, rather than strain, the democratic process. This dual focus will be critical in shaping the future of American elections.

Comparing Political Giants: Which Party Holds More Power and Influence?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political parties began to significantly influence the Electoral College in the late 1790s, with the emergence of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties during the presidency of George Washington and John Adams.

By the 1830s, political parties had gained near-complete control over the selection of presidential electors, as the process shifted from state legislatures to popular votes influenced by party organizations.

The modern system of political parties dominating the Electoral College solidified in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with the establishment of party primaries and the widespread adoption of winner-take-all systems in most states.