The origins of political parties in South Africa can be traced back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, coinciding with the country's evolving political landscape under colonial and later apartheid rule. The first notable political organizations emerged in response to the increasing disenfranchisement of Black Africans and the consolidation of power by the white minority. One of the earliest formations was the African National Congress (ANC), founded in 1912 as the South African Native National Congress, which aimed to advocate for the rights of Black South Africans. Concurrently, the National Party, established in 1914, represented the interests of Afrikaners and later became the architect of apartheid in 1948. These early political entities laid the groundwork for the polarized and racially defined party system that would dominate South African politics for much of the 20th century, culminating in the democratic transition in 1994.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Early Political Movements

The roots of South Africa's political parties trace back to the late 19th century, a period marked by colonial expansion, economic shifts, and growing resistance to racial oppression. One of the earliest organized movements was the South African Native National Congress (SANNC), founded in 1912, which later became the African National Congress (ANC). This movement emerged as a response to the 1913 Natives Land Act, which restricted Black land ownership to just 7% of South Africa. The SANNC's formation was a pivotal moment, as it sought to unite African communities across tribal lines and advocate for political and economic rights. Its leaders, such as John Dube and Sol Plaatje, emphasized non-violent protest and petitioning, reflecting a strategy of engagement with colonial authorities rather than confrontation.

Parallel to the SANNC, the Cape Coloured community also began organizing in the early 20th century. The African Political Organization (APO), established in 1902, was one of the first political movements representing this group. The APO focused on protecting the limited political rights of Coloureds in the Cape Colony, which were under threat as the Union of South Africa was formed in 1910. Their efforts highlighted the fragmented nature of early political movements, as different racial groups mobilized separately to address their unique grievances. This period underscores the importance of understanding the diverse origins of South Africa's political landscape, where movements were often shaped by the specific challenges faced by their constituents.

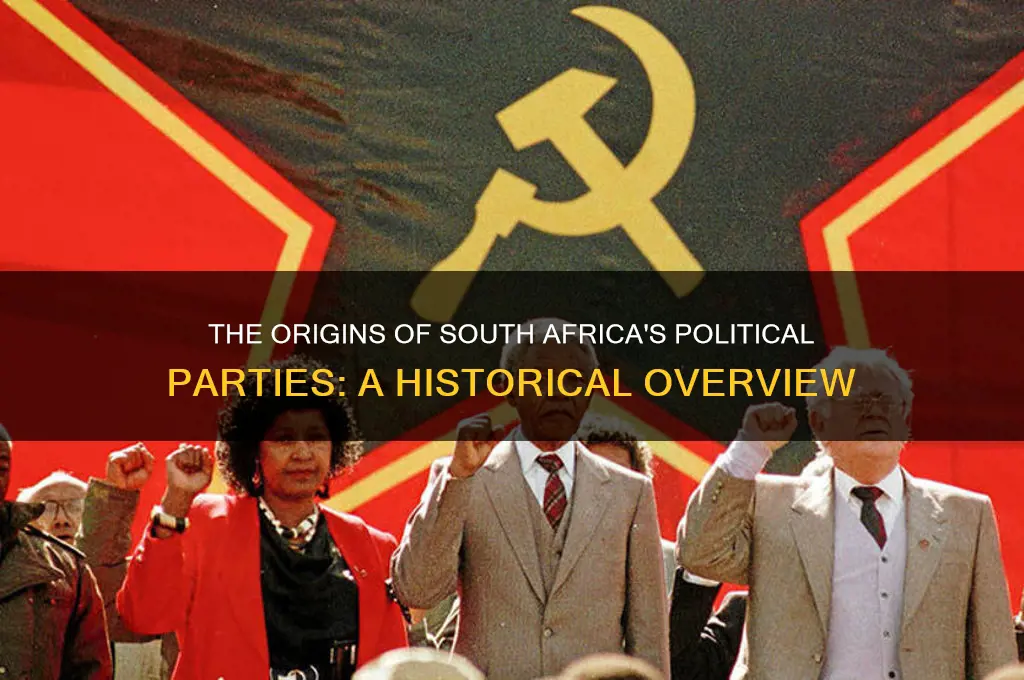

Another critical early movement was the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA), founded in 1921. Unlike the SANNC or APO, the CPSA was multiracial and focused on class struggle rather than racial identity. It played a significant role in organizing workers and advocating for labor rights, particularly during the 1922 Rand Rebellion. The CPSA's alliance with the ANC in the 1920s marked one of the first attempts at cross-racial political cooperation, though it was short-lived due to ideological differences. This movement illustrates how early political parties in South Africa were not only defined by race but also by economic and ideological divides, adding complexity to the nation's political evolution.

A lesser-known but influential movement was the Industrial and Commercial Workers' Union (ICU), which emerged in the 1920s. The ICU began as a labor union but quickly evolved into a broader political movement, addressing land rights, economic exploitation, and political representation. At its peak, it had over 100,000 members across South Africa, making it one of the largest mass movements of its time. However, internal conflicts and government repression led to its decline by the 1930s. The ICU's rise and fall serve as a cautionary tale about the challenges of sustaining early political movements in the face of internal divisions and external oppression.

In analyzing these early movements, it becomes clear that South Africa's political parties were born out of necessity, shaped by the harsh realities of colonialism and racial segregation. Each movement, whether focused on racial unity, labor rights, or class struggle, contributed to the foundation of the country's modern political landscape. Their legacies remind us that the fight for justice and equality is often fragmented, requiring diverse strategies and sustained effort. For those studying or engaging with South Africa's history, understanding these early movements provides invaluable insights into the roots of contemporary political struggles.

Understanding the Politico: A Deep Dive into Political Enthusiasts

You may want to see also

Formation of ANC (1912)

The African National Congress (ANC) was founded in 1912 as the South African Native National Congress (SANNC), marking a pivotal moment in the country's political history. This formation was a direct response to the escalating racial discrimination and disenfranchisement of Black Africans under colonial and early Union of South Africa governments. The SANNC, later renamed the ANC in 1923, emerged as a unified voice for African grievances, advocating for political and social rights in a society increasingly dominated by white minority rule. Its establishment reflected a growing awareness among African leaders of the need for organized resistance against systemic oppression.

The ANC's early years were characterized by moderate strategies, such as petitions and delegations to authorities, aimed at securing basic rights and representation. Key figures like John Dube, Sol Plaatje, and Pixley ka Isaka Seme played instrumental roles in shaping its vision. Despite these efforts, the ANC faced significant challenges, including limited resources and a fragmented membership base. The organization's initial approach, though non-confrontational, laid the groundwork for more radical movements in later decades. This period highlights the complexities of political mobilization in a deeply segregated society.

A critical takeaway from the ANC's formation is its role as a unifying force for diverse African communities. By bringing together chiefs, intellectuals, and ordinary citizens, the ANC transcended tribal and regional divides, fostering a collective identity rooted in shared struggles. This unity became a cornerstone of its resilience and longevity, enabling it to adapt to changing political landscapes. For modern political movements, the ANC's early emphasis on inclusivity and grassroots engagement offers valuable lessons in building sustainable coalitions.

Practical tips for understanding the ANC's formation include studying its foundational documents, such as the 1912 manifesto, which articulated its goals and principles. Engaging with primary sources, like Sol Plaatje's writings, provides deeper insights into the motivations and challenges of its leaders. Additionally, comparing the ANC's early strategies with those of contemporary movements can illuminate the evolution of resistance tactics. For educators and activists, incorporating these historical specifics into discussions fosters a more nuanced appreciation of South Africa's political heritage.

In conclusion, the formation of the ANC in 1912 was a transformative event that reshaped South Africa's political trajectory. Its origins underscore the power of organized resistance in confronting systemic injustice. By examining its early years, we gain not only historical insight but also practical guidance for addressing contemporary issues of inequality and oppression. The ANC's legacy serves as a reminder that unity, perseverance, and strategic adaptation are essential for meaningful social change.

Exploring the Rise of the Younger Political Party: A New Era?

You may want to see also

National Party's Rise (1948)

The National Party's rise to power in South Africa in 1948 marked a pivotal moment in the country's history, cementing the institutionalization of apartheid. This event was not merely a political shift but a deliberate, calculated move to entrench racial segregation through legislative means. The party's victory, secured with a slim majority in the House of Assembly, was fueled by a campaign that exploited fears of racial integration and economic competition, particularly among the Afrikaner population. Their slogan, "Die kaffer op sy plek" (The native in his place), succinctly captured their agenda, which would soon be codified into law.

To understand the National Party's ascent, one must examine the socio-economic context of post-World War II South Africa. The United Party, led by Jan Smuts, had governed since 1934 but faced growing discontent. Smuts’s liberal stance on racial issues, including his support for limited black political rights and his involvement in international affairs, alienated conservative Afrikaners. The National Party, under the leadership of D.F. Malan, capitalized on this discontent by positioning itself as the defender of Afrikaner interests. They promised to protect white jobs, restrict black urbanization, and maintain racial hierarchies, resonating deeply with a population anxious about their economic and cultural survival.

The implementation of apartheid began almost immediately after the National Party took office. Key legislation, such as the Group Areas Act (1950) and the Population Registration Act (1950), systematically segregated South Africans by race, dictating where they could live, work, and socialize. These laws were not just administrative measures but tools of social engineering, designed to reinforce white supremacy. The Pass Laws, tightened under apartheid, further restricted black mobility, making it nearly impossible for black South Africans to move freely without documentation. Each piece of legislation was a step toward the National Party’s vision of a racially stratified society.

Critically, the National Party’s rise was not inevitable. The 1948 election was closely contested, with the National Party winning only 40% of the popular vote but securing a majority of seats due to the electoral system’s biases. This highlights the fragility of their mandate and the role of structural factors in their victory. Had the United Party’s coalition held, or had the electoral system been more representative, South Africa’s history might have unfolded differently. Instead, the National Party’s win became a turning point, locking the country into decades of state-sanctioned racism and international isolation.

In retrospect, the National Party’s rise serves as a cautionary tale about the power of fear-based politics and the dangers of majoritarianism. Their ability to mobilize a constituency around a divisive agenda underscores the importance of inclusive governance and equitable institutions. For modern societies grappling with polarization, the 1948 election offers a stark reminder: political parties that exploit racial or ethnic divisions can reshape nations in profound and often irreversible ways. Understanding this history is not just an academic exercise but a practical guide to safeguarding democracy against authoritarian impulses.

Tom Hanks' Political Views: Uncovering the Actor's Beliefs and Activism

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Apartheid-Era Politics

The apartheid era in South Africa, spanning from 1948 to 1994, was defined by a rigid racial hierarchy enforced through legislation, with political parties playing a central role in both perpetuating and resisting this system. The National Party (NP), a predominantly Afrikaner organization, rose to power in 1948 and institutionalized apartheid, creating a framework that marginalized non-white populations. This period saw the emergence of political parties as tools of both oppression and liberation, with the NP using its majority to pass laws like the Group Areas Act and the Population Registration Act, while opposition parties like the African National Congress (ANC) were forced underground or into exile.

To understand the dynamics of apartheid-era politics, consider the stark contrast between the NP’s state-sanctioned dominance and the ANC’s grassroots resistance. The NP controlled all levers of government, including the media and judiciary, to suppress dissent. For instance, the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre, where police killed 69 anti-pass law protesters, exemplified the state’s brutal response to opposition. Meanwhile, the ANC, led by figures like Nelson Mandela, adopted a dual strategy of non-violent civil disobedience and, later, armed struggle through its military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK). This period underscores how political parties became the primary vehicles for either maintaining or dismantling apartheid.

A critical takeaway from apartheid-era politics is the role of international pressure in shaping domestic political dynamics. While internal resistance was relentless, external sanctions and global condemnation isolated the apartheid regime. Political parties like the ANC leveraged this international solidarity, gaining financial and logistical support from countries like Sweden and the Soviet Union. Conversely, the NP’s attempts to legitimize apartheid through pseudo-reforms, such as the creation of the Tricameral Parliament in 1984, were widely rejected. This interplay between internal struggle and external influence highlights the interconnectedness of political movements during this era.

Practical lessons from apartheid-era politics include the importance of unity and adaptability in resistance movements. The ANC’s ability to unite diverse ethnic groups under a common cause was pivotal, as was its willingness to shift strategies—from non-violence to armed struggle and back to negotiations. For modern political movements, this underscores the need for flexibility and inclusivity. Conversely, the NP’s downfall illustrates the dangers of rigid ideology and the inability to respond to changing realities. Both examples offer valuable insights for contemporary political organizing.

Finally, apartheid-era politics serve as a cautionary tale about the consequences of state-sponsored division. The NP’s policies not only entrenched racial inequality but also sowed deep social and economic divisions that persist today. Political parties, whether in power or opposition, must prioritize reconciliation and justice over exclusionary agendas. The transition to democracy in 1994, marked by the ANC’s victory in the first multiracial elections, demonstrates the potential for transformative change when political parties prioritize inclusivity and human rights. This legacy remains a guiding principle for South Africa’s ongoing political evolution.

Why Political Parties Matter: Shaping Policies, Societies, and Our Future

You may want to see also

Post-Apartheid Multiparty System

South Africa's transition to a multiparty system post-apartheid marked a pivotal shift in its political landscape, rooted in the democratic elections of 1994. This watershed moment not only dismantled the apartheid regime but also laid the foundation for a competitive political environment. The African National Congress (ANC), historically a liberation movement, emerged as the dominant party, winning the first democratic elections with 62.65% of the vote. However, the inclusion of other parties like the National Party (NP), Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), and Democratic Party (DP) signaled the birth of a multiparty democracy. This system was enshrined in the 1996 Constitution, which guarantees political pluralism and the right to form and participate in political parties.

The post-apartheid multiparty system is characterized by its diversity, reflecting South Africa's complex social and ethnic makeup. Parties like the IFP, rooted in Zulu nationalism, and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), advocating for Africanist ideals, highlight the system's ability to accommodate diverse ideologies. Over time, new parties such as the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), formed in 2013, have emerged to challenge the ANC's dominance, particularly on issues of economic inequality and corruption. This evolution demonstrates the system's adaptability and responsiveness to shifting public sentiments. However, the ANC's prolonged dominance has also raised concerns about democratic consolidation, as opposition parties struggle to gain significant traction at the national level.

A critical aspect of South Africa's multiparty system is its role in fostering accountability and representation. The proportional representation electoral system ensures that smaller parties have a voice in Parliament, even if they cannot win majority seats. For instance, the Democratic Alliance (DA), initially a minority party, has grown to become the official opposition, holding the ANC accountable on issues like service delivery and governance. Yet, the system is not without challenges. Factionalism within parties, allegations of state capture, and voter apathy threaten its stability. Strengthening institutions like the Electoral Commission and promoting intra-party democracy are essential steps to address these issues.

To navigate South Africa's multiparty system effectively, citizens must engage critically with political parties' manifestos and track records. Practical tips include attending local party meetings, participating in voter education programs, and using social media to hold representatives accountable. For example, platforms like "My Vote Counts" provide tools to analyze party funding and performance. Additionally, younger voters (aged 18–35) should leverage their demographic weight to push for policies addressing unemployment and education. By actively participating in the political process, citizens can ensure the multiparty system fulfills its promise of inclusive democracy.

In conclusion, South Africa's post-apartheid multiparty system is a testament to its commitment to democratic ideals, though it faces challenges that require ongoing vigilance and reform. Its success hinges on the ability of citizens, parties, and institutions to uphold transparency, accountability, and inclusivity. As the system continues to evolve, it remains a critical mechanism for addressing the nation's historical and contemporary inequalities.

Planned Parenthood's Political Impact: Shaping Party Platforms and Voter Loyalties

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political parties in South Africa began to emerge in the late 19th century, with the formation of the South African Party in 1911, which was one of the first major political parties in the country.

The first significant political party in South Africa was the South African Party, established in 1911, which later merged with the Unionist Party to form the United Party in 1934.

The African National Congress (ANC) was founded in 1912 as the South African Native National Congress (SANNC) and later renamed the ANC in 1923, making it one of the oldest political parties in South Africa.

Multi-party democracy in South Africa began with the first non-racial democratic elections in 1994, following the end of apartheid, allowing all political parties to participate freely in the electoral process.