The 1796 United States presidential election marked a pivotal moment in American political history as it was the first contested presidential election and the first to feature the emergence of distinct political parties. The two dominant parties at the time were the Federalist Party, led by figures such as Alexander Hamilton, and the Democratic-Republican Party, spearheaded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. The Federalists, who had largely shaped the early federal government under George Washington, advocated for a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain. In contrast, the Democratic-Republicans championed states' rights, agrarian interests, and a more limited federal government, while favoring closer relations with France. This election not only solidified the two-party system but also highlighted the ideological divisions that would define early American politics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Names | Federalist Party and Democratic-Republican Party |

| Founding Years | Federalist Party (1791), Democratic-Republican Party (1792) |

| Key Leaders | Federalist: Alexander Hamilton, John Adams; Democratic-Republican: Thomas Jefferson, James Madison |

| Ideology | Federalist: Strong central government, pro-commerce; Democratic-Republican: States' rights, agrarian focus |

| Base of Support | Federalist: Urban merchants, New England; Democratic-Republican: Southern and Western farmers |

| Views on Constitution | Federalist: Loose interpretation (implied powers); Democratic-Republican: Strict interpretation |

| Foreign Policy | Federalist: Pro-British; Democratic-Republican: Pro-French |

| Economic Policies | Federalist: Supported national bank, tariffs; Democratic-Republican: Opposed national bank, favored states' control |

| First Presidential Election | 1796: Federalist John Adams won presidency; Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson became Vice President |

| Legacy | Shaped early American political system; laid groundwork for two-party politics |

Explore related products

$32 $31.99

$21.29 $26.5

What You'll Learn

- Federalist Party: Supported strong central government, led by Alexander Hamilton, favored urban and commercial interests

- Democratic-Republican Party: Advocated states' rights, led by Thomas Jefferson, favored agrarian and rural interests

- Key Issues: Economic policies, foreign relations, and the role of the federal government divided the parties

- Election: First contested presidential election, John Adams (Federalist) vs. Thomas Jefferson (Democratic-Republican)

- Party Origins: Emerged from debates over the Constitution, Bill of Rights, and Hamilton’s financial plans

Federalist Party: Supported strong central government, led by Alexander Hamilton, favored urban and commercial interests

The Federalist Party, emerging in the late 18th century, was a cornerstone of early American politics, advocating for a robust central government as the backbone of a stable and prosperous nation. Led by Alexander Hamilton, the party’s vision was shaped by the belief that a strong federal authority was essential to address the economic and security challenges of the post-Revolutionary era. Hamilton, as the first Secretary of the Treasury, championed policies that centralized financial power, such as the establishment of a national bank and the assumption of state debts by the federal government. These measures were not merely administrative; they were ideological, reflecting the Federalists’ commitment to creating a cohesive and economically vibrant union.

To understand the Federalist Party’s appeal, consider its focus on urban and commercial interests. Unlike their opponents, the Democratic-Republicans, who favored agrarian ideals, the Federalists prioritized the growth of cities and trade. They believed that a strong central government could foster economic development by protecting industries, regulating commerce, and promoting infrastructure projects like roads and canals. For instance, Hamilton’s Report on Manufactures (1791) outlined a blueprint for industrial expansion, advocating tariffs and subsidies to shield American businesses from foreign competition. This urban and commercial focus resonated with merchants, bankers, and industrialists, who saw the Federalists as their political allies in a rapidly changing economy.

However, the Federalist Party’s emphasis on centralization was not without controversy. Critics argued that their policies favored the elite at the expense of the common man, particularly farmers and rural populations. The party’s support for the Alien and Sedition Acts (1798), which restricted civil liberties in the name of national security, further alienated many Americans. These measures, though intended to protect the young nation from internal and external threats, were seen as authoritarian and contrary to the principles of individual freedom. The backlash against these policies contributed to the Federalists’ decline, yet their legacy in shaping the role of the federal government remains undeniable.

Practical takeaways from the Federalist Party’s ideology can still be applied today. For those in leadership roles, the Federalists’ focus on long-term economic planning and infrastructure investment offers a model for fostering national growth. Policymakers can learn from Hamilton’s approach to financial stability, such as the importance of a centralized banking system and debt management. However, caution must be exercised to balance central authority with individual rights, a lesson learned from the party’s missteps. By studying the Federalists, modern leaders can navigate the tension between government power and personal liberty, ensuring policies serve both the nation’s interests and its people.

In conclusion, the Federalist Party’s advocacy for a strong central government, led by Alexander Hamilton’s visionary policies, laid the groundwork for America’s economic and political development. Their focus on urban and commercial interests reflected a forward-thinking approach to nation-building, though it was not without flaws. By examining their successes and failures, we gain insights into the enduring challenges of governance, offering lessons that remain relevant in contemporary political discourse.

Pepsi's Political Leanings: Uncovering the Brand's Party Affiliation

You may want to see also

Democratic-Republican Party: Advocated states' rights, led by Thomas Jefferson, favored agrarian and rural interests

The Democratic-Republican Party, emerging in the late 18th century, was a pivotal force in shaping early American politics. Led by Thomas Jefferson, this party championed states' rights as a cornerstone of its ideology, directly opposing the Federalist Party's emphasis on a strong central government. This stance was not merely theoretical; it reflected a deep-seated belief in the sovereignty of individual states and their ability to govern themselves effectively. By advocating for states' rights, the Democratic-Republicans sought to limit federal power, ensuring that local communities retained control over their affairs. This principle resonated particularly with those who feared the concentration of authority in distant, centralized institutions.

Jefferson's leadership was instrumental in defining the party's identity. As a staunch advocate for agrarian and rural interests, he positioned the Democratic-Republicans as the voice of farmers, planters, and rural communities. Unlike the Federalists, who favored urban commercial and industrial growth, Jefferson believed that the nation's strength lay in its agricultural base. This focus on agrarianism was not just economic but also philosophical, rooted in the idea that self-sufficient farmers were the backbone of a virtuous republic. Policies such as reducing federal taxes and promoting land ownership for small farmers underscored this commitment, appealing to those who felt marginalized by Federalist policies favoring bankers and merchants.

The party's emphasis on rural interests extended beyond economics to a broader vision of American society. Democratic-Republicans idealized a nation of independent, land-owning citizens, free from the corruption and dependencies they associated with urban life. This vision was encapsulated in Jefferson's concept of the "yeoman farmer," a figure who embodied self-reliance, civic virtue, and democratic participation. By prioritizing rural over urban development, the party sought to create a society where political power was decentralized and accessible to the common man, rather than concentrated in the hands of a wealthy elite.

Practically, the Democratic-Republicans' advocacy for states' rights and agrarian interests had tangible implications for governance. They opposed measures like the national bank and federal infrastructure projects, arguing that such initiatives encroached on state authority and benefited urban commercial interests at the expense of rural communities. Instead, they favored policies that strengthened local economies, such as land ordinances and the reduction of tariffs that burdened farmers. This approach not only reflected their ideological commitments but also served as a strategic tool to build a broad coalition of supporters across the South and West, regions dominated by agrarian economies.

In conclusion, the Democratic-Republican Party's advocacy for states' rights and agrarian interests was more than a political platform; it was a vision for the future of the United States. Under Jefferson's leadership, the party articulated a compelling alternative to Federalist centralization, one that resonated deeply with rural Americans. Their legacy endures in the ongoing American debate over the balance between federal and state power, as well as in the enduring idealization of rural life as a cornerstone of national identity. Understanding their principles offers valuable insights into the foundational tensions that continue to shape American politics.

Polarization and Gridlock: A Key Criticism of Political Parties

You may want to see also

Key Issues: Economic policies, foreign relations, and the role of the federal government divided the parties

The 1796 presidential election marked the first contested race in American history, pitting the Federalist Party against the Democratic-Republican Party. These two parties, though nascent, were deeply divided over the nation's economic trajectory, its place in the world, and the appropriate scope of federal power. These divisions were not merely philosophical but had tangible implications for the young republic's future.

Economic Policies: The Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, championed a strong central government and a market-driven economy. They advocated for a national bank, protective tariffs, and federal assumption of state debts, believing these measures would foster economic growth and stability. In contrast, Thomas Jefferson's Democratic-Republicans favored an agrarian economy, states' rights, and limited federal intervention. They viewed Hamilton's financial policies as favoring the wealthy elite and feared they would lead to corruption and tyranny. This economic divide reflected differing visions of America's future: one urban, industrial, and commercially oriented, the other rural, agricultural, and decentralized.

Foreign Relations: The French Revolution further polarized the parties. Federalists, wary of revolutionary fervor and committed to stability, aligned with Britain, America's largest trading partner. They supported the Jay Treaty, which resolved lingering issues from the Revolutionary War but alienated France. Democratic-Republicans, sympathetic to the French cause and distrustful of British influence, opposed the treaty and advocated for closer ties with France. This foreign policy rift was exacerbated by the Quasi-War with France, which erupted in 1798, highlighting the parties' divergent views on America's role in the world.

The Role of the Federal Government: At the heart of these disputes was a fundamental disagreement over the role of the federal government. Federalists believed in a strong, active central government necessary to ensure national unity and economic prosperity. They supported broad interpretations of the Constitution, such as Hamilton's implied powers doctrine. Democratic-Republicans, however, feared centralized power and championed states' rights and strict constructionism. They saw the Federalists' expansive view of government as a threat to individual liberty and state sovereignty. This ideological clash set the stage for decades of political conflict and shaped the American political landscape.

Practical Implications: Understanding these divisions offers insights into modern political debates. The Federalist-Democratic-Republican split foreshadowed contemporary arguments over federalism, economic policy, and foreign intervention. For instance, debates over healthcare, taxation, and international alliances often echo the 1796 parties' concerns. By studying this era, we can better navigate today's political challenges, recognizing that many current issues have deep historical roots. This historical perspective encourages a more nuanced approach to policy-making, balancing central authority with local autonomy and economic growth with social equity.

Can Military Leaders Transition to Political Party Leadership Effectively?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$39.7 $65

1796 Election: First contested presidential election, John Adams (Federalist) vs. Thomas Jefferson (Democratic-Republican)

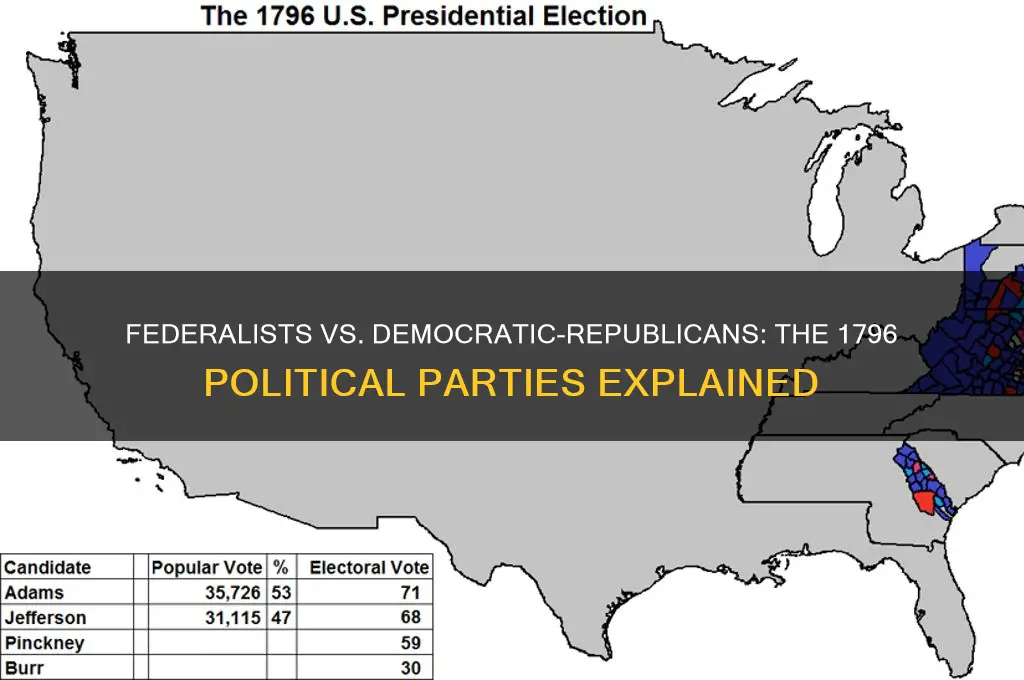

The 1796 U.S. presidential election marked a pivotal moment in American political history as the first truly contested race between two distinct parties: the Federalists, led by John Adams, and the Democratic-Republicans, fronted by Thomas Jefferson. This election not only solidified the two-party system but also highlighted the ideological divides that would shape the nation’s future. Adams, a staunch Federalist, advocated for a strong central government, a national bank, and close ties with Britain, while Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans championed states’ rights, agrarian interests, and alignment with France. Their clash set the stage for a campaign that would define American politics for decades.

To understand the significance of this election, consider the mechanics of the Electoral College at the time. Electors cast two votes, with the candidate receiving the most votes becoming president and the runner-up vice president. This system, though flawed, forced Adams and Jefferson into an uneasy partnership despite their opposing views. The campaign itself was marked by intense partisan rhetoric, with Federalists portraying Jefferson as an atheist radical and Democratic-Republicans labeling Adams a monarchist. Newspapers, the primary medium of the era, became battlegrounds for these attacks, illustrating the growing power of media in shaping public opinion.

Analyzing the outcomes reveals the regional divides of early America. Adams secured victories in New England, where Federalist ideals of industrialization and central authority resonated, while Jefferson dominated the South, where agrarian economies and states’ rights held sway. The Middle Atlantic states became the decisive battleground, with Adams narrowly winning the presidency by a margin of just three electoral votes. This regional split foreshadowed the sectional tensions that would later plague the nation, particularly over issues like slavery and economic policy.

For modern readers, the 1796 election offers a practical lesson in the importance of understanding political ideologies. Adams’ Federalist vision of a strong, unified nation contrasted sharply with Jefferson’s emphasis on individual liberty and local control. These competing philosophies continue to influence American politics today, with debates over federal power versus states’ rights remaining central to policy discussions. By studying this election, one can trace the origins of contemporary political divisions and gain insight into the enduring struggle between centralization and decentralization.

Finally, the 1796 election serves as a cautionary tale about the unintended consequences of political systems. The Electoral College’s structure, designed to foster unity, instead forced ideological opponents into the highest offices. This awkward arrangement led to gridlock and tension during Adams’ presidency, as Jefferson’s presence as vice president undermined Federalist agendas. This historical example underscores the need for thoughtful institutional design in democratic systems, ensuring that mechanisms intended to promote stability do not inadvertently sow discord.

Changing Political Party Affiliation in Michigan: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Party Origins: Emerged from debates over the Constitution, Bill of Rights, and Hamilton’s financial plans

The two dominant political parties in 1796, the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans, were not born out of modern campaign strategies or ideological branding. Instead, their origins trace back to the intense debates surrounding the ratification of the Constitution, the creation of the Bill of Rights, and Alexander Hamilton’s ambitious financial plans. These foundational disputes laid bare the philosophical divides that would define early American politics.

Consider the Constitution itself: Federalists, led by figures like Hamilton and John Adams, championed a strong central government as essential for national stability and economic growth. They viewed the Constitution as a necessary corrective to the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation. In contrast, Anti-Federalists, who later coalesced into the Democratic-Republican Party under Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, feared centralized power and argued for stronger state authority and individual liberties. The compromise that emerged—the addition of the Bill of Rights—was a direct response to Anti-Federalist concerns, yet it did not resolve the underlying tension between federal and state power.

Hamilton’s financial plans further deepened these divisions. As the first Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton proposed a national bank, the assumption of state debts, and a system of tariffs and excise taxes to stabilize the economy. Federalists embraced these measures as vital for establishing American credit and fostering industrial growth. Democratic-Republicans, however, saw them as favoring the wealthy elite and consolidating federal power at the expense of agrarian interests and state autonomy. The Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, sparked by resistance to Hamilton’s excise tax, exemplified the clash between these competing visions.

To understand the practical implications of these debates, imagine a farmer in 1796 deciding which party to support. A Federalist vote would align with policies promoting economic modernization and national unity, while a Democratic-Republican vote would reflect a commitment to local control and agrarian values. This choice was not merely ideological but had tangible consequences for livelihoods and communities.

In essence, the emergence of the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans was not a sudden development but the culmination of years of debate over the role of government, the balance of power, and economic priorities. These early divisions set the stage for the two-party system that continues to shape American politics today, reminding us that the roots of political conflict often lie in fundamental questions about governance and society.

John Adams' Political Party Affiliation: A Historical Overview

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The two main political parties in 1796 were the Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican Party.

The Federalist Party was led by John Adams, while the Democratic-Republican Party was led by Thomas Jefferson.

Federalists favored a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain, while Democratic-Republicans advocated for states' rights, agrarianism, and closer relations with France.

The Federalist Party won the 1796 election, and John Adams became the second President of the United States.