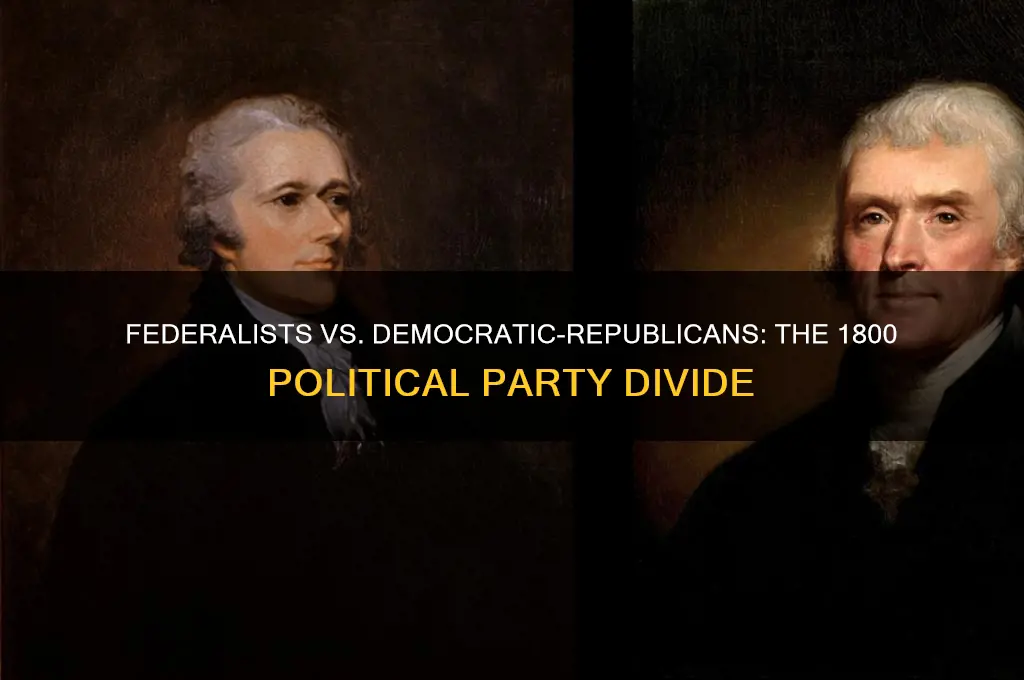

In 1800, the United States was dominated by two major political parties: the Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican Party. The Federalists, led by figures such as Alexander Hamilton and John Adams, advocated for a strong central government, a national bank, and close ties with Britain. In contrast, the Democratic-Republicans, spearheaded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, championed states' rights, agrarian interests, and a more limited federal government, while favoring closer relations with France. The election of 1800, a pivotal moment in American history, marked the first peaceful transfer of power between these opposing parties, with Jefferson’s victory signaling a shift toward Democratic-Republican ideals and the decline of Federalist influence.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Names | Federalist Party, Democratic-Republican Party |

| Founding Years | Federalist: 1789-1791, Democratic-Republican: 1792 |

| Key Leaders | Federalist: Alexander Hamilton, John Adams; Democratic-Republican: Thomas Jefferson, James Madison |

| Ideology | Federalist: Strong central government, pro-commerce; Democratic-Republican: States' rights, agrarian focus |

| Base of Support | Federalist: Urban merchants, New England; Democratic-Republican: Southern planters, Western farmers |

| Views on Constitution | Federalist: Loose interpretation (implied powers); Democratic-Republican: Strict interpretation |

| Foreign Policy | Federalist: Pro-British; Democratic-Republican: Pro-French |

| Banking and Economy | Federalist: Supported national bank; Democratic-Republican: Opposed national bank |

| Notable Achievements | Federalist: Established financial system; Democratic-Republican: Louisiana Purchase |

| Decline | Federalist: Early 1800s after War of 1812; Democratic-Republican: Evolved into Democratic Party |

Explore related products

$32 $31.99

$21.29 $26.5

What You'll Learn

- Federalist Party: Supported strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain

- Democratic-Republican Party: Advocated states' rights, agrarian economy, and republican ideals

- Key Leaders: Federalists led by Alexander Hamilton; Jefferson and Madison led Democratic-Republicans

- Election of 1800: A tie between Jefferson and Burr resolved by the House of Representatives

- Ideological Divide: Federalists favored elites; Democratic-Republicans championed common farmers and rural interests

Federalist Party: Supported strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain

The Federalist Party, one of the two dominant political parties in the United States during the early 1800s, championed a vision of governance that prioritized unity, progress, and strategic international alliances. At its core, the party advocated for a strong central government, believing it essential for maintaining order, fostering economic growth, and ensuring national security. This stance contrasted sharply with the Democratic-Republican Party, which favored states’ rights and agrarian interests. By examining the Federalists’ support for industrialization and their close ties with Britain, we can better understand their role in shaping early American politics and policy.

Industrialization was a cornerstone of Federalist ideology, as they recognized its potential to transform the young nation into an economic powerhouse. While the Democratic-Republicans idealized a rural, agrarian society, the Federalists embraced manufacturing, infrastructure development, and technological innovation. They championed initiatives like the establishment of a national bank, protective tariffs, and internal improvements such as roads and canals. For instance, Alexander Hamilton’s Report on Manufactures (1791) outlined a blueprint for industrial growth, emphasizing the need for government intervention to nurture domestic industries. This forward-thinking approach aimed to reduce American dependence on foreign goods and position the nation as a global economic competitor.

The Federalists’ advocacy for close ties with Britain was both pragmatic and controversial. In the aftermath of the Revolutionary War, they argued that maintaining a strong relationship with Britain was crucial for economic stability and national security. Britain was America’s largest trading partner, and Federalists believed that fostering commercial ties would benefit both nations. This stance was evident in the Jay Treaty of 1794, which resolved lingering issues from the war and expanded trade opportunities. However, this alignment with Britain alienated many Americans, particularly those who viewed Britain as an oppressive former colonizer. Critics accused the Federalists of prioritizing elite interests over the will of the people, a charge that would contribute to the party’s eventual decline.

A comparative analysis reveals the Federalists’ unique position in the political landscape of 1800. While their emphasis on central authority and industrialization laid the groundwork for modern American governance, their pro-British stance limited their appeal in a nation still defining its identity. The party’s policies were often perceived as elitist, catering to merchants, bankers, and industrialists rather than the common farmer or laborer. This disconnect ultimately paved the way for the rise of the Democratic-Republicans, who capitalized on populist sentiments and a distrust of centralized power.

In practical terms, the Federalist Party’s legacy is evident in the enduring structures of American government and economy. Their push for a strong central authority influenced the development of federal institutions, while their support for industrialization set the stage for the nation’s economic ascendancy. For modern policymakers, the Federalists offer a cautionary tale about balancing national interests with public sentiment. While their vision was ambitious and forward-looking, their inability to connect with the broader population underscores the importance of inclusivity in political strategy. By studying the Federalists, we gain insights into the complexities of early American politics and the enduring tension between progress and populism.

Labour Party: The Main Political Opponent to the UK Tories

You may want to see also

Democratic-Republican Party: Advocated states' rights, agrarian economy, and republican ideals

The Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson, emerged in the late 18th century as a counter to the Federalist Party, shaping early American politics with its distinct principles. At its core, the party championed states’ rights, arguing that the federal government should have limited power, allowing individual states to govern themselves with greater autonomy. This stance was a direct response to Federalists’ centralizing tendencies, which Democratic-Republicans viewed as a threat to liberty. By prioritizing states’ rights, the party sought to preserve local control and prevent the concentration of power in Washington, D.C.

Another cornerstone of the Democratic-Republican platform was its advocacy for an agrarian economy. The party idealized the independent farmer as the backbone of American society, believing that agriculture fostered self-reliance, virtue, and stability. This vision stood in stark contrast to the Federalists’ emphasis on commerce, banking, and industrialization. Democratic-Republicans opposed policies like Alexander Hamilton’s national bank, arguing that such institutions favored urban elites at the expense of rural communities. Their agrarian focus reflected a broader belief in a decentralized, rural-based economy as the foundation of a healthy republic.

Beyond states’ rights and agrarianism, the party was deeply committed to republican ideals, which emphasized civic virtue, public participation, and resistance to corruption. Democratic-Republicans feared the rise of aristocracy and sought to protect the common man from the influence of wealthy elites. They promoted a simple, frugal government, rejecting lavish displays of power and advocating for leaders who embodied the values of the people. This commitment to republicanism was not merely theoretical; it influenced practical policies, such as reducing the national debt and limiting the size of the military, to ensure that government remained accessible and accountable to citizens.

To understand the Democratic-Republican Party’s impact, consider its legacy in modern American politics. Its emphasis on states’ rights continues to resonate in debates over federal versus state authority, while its agrarian ideals laid the groundwork for later movements advocating for rural interests. Practically, individuals today can draw from these principles by engaging in local governance, supporting small-scale agriculture, and advocating for policies that prioritize community over centralized power. By studying the Democratic-Republican Party, we gain insights into how foundational political philosophies still shape contemporary discourse and action.

Essential Political Reforms to Revitalize Democracy and Governance Today

You may want to see also

Key Leaders: Federalists led by Alexander Hamilton; Jefferson and Madison led Democratic-Republicans

The early 1800s marked a pivotal era in American politics, defined by the rivalry between the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. At the helm of these factions were visionary leaders whose ideologies shaped the nation’s trajectory. Alexander Hamilton, the architect of the Federalist Party, championed a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain. His policies, such as the establishment of a national bank and assumption of state debts, laid the groundwork for America’s economic modernization. Hamilton’s leadership was characterized by pragmatism and a belief in elite governance, which, while forward-thinking, alienated agrarian interests and fueled opposition.

In contrast, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, the intellectual powerhouses of the Democratic-Republican Party, advocated for states’ rights, agrarian democracy, and a limited federal government. Jefferson’s vision, encapsulated in his agrarian ideal, emphasized the virtues of the common farmer and warned against the corrupting influence of centralized power. Madison, often called the Father of the Constitution, complemented Jefferson’s philosophy with his deep understanding of political theory, crafting the Bill of Rights and championing checks and balances. Together, they framed their party as the defender of individual liberties against Federalist elitism.

The leadership styles of these figures mirrored their ideologies. Hamilton’s Federalist Party operated as a tightly organized, top-down entity, reflecting his belief in a strong executive and financial order. Jefferson and Madison, however, fostered a more decentralized, grassroots approach, aligning with their commitment to local control and democratic participation. This divergence in leadership not only defined the parties but also set the stage for the nation’s first peaceful transfer of power in the 1800 election, a testament to the enduring impact of their rivalry.

To understand the legacy of these leaders, consider their practical contributions. Hamilton’s financial system stabilized the post-Revolutionary economy, while Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase doubled the nation’s size. Madison’s role in shaping constitutional governance ensured a balance of power that endures today. For modern readers, studying these leaders offers a blueprint for navigating political divides: Hamilton’s emphasis on infrastructure and Jefferson’s focus on individual rights remain relevant in debates over federal authority versus personal freedoms.

In practice, educators and historians can use this era to illustrate the importance of leadership in shaping policy. For instance, a classroom exercise could compare Hamilton’s economic plans with Jefferson’s agrarian policies, asking students to evaluate which approach better suits contemporary challenges. Similarly, policymakers can draw lessons from Madison’s ability to bridge ideological gaps, a skill critical in today’s polarized political landscape. By examining these leaders, we gain not just historical insight but also tools for addressing modern governance dilemmas.

Understanding the Democratic Party's Political Representation and Core Values

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$39.7 $65

$16.17 $29.95

Election of 1800: A tie between Jefferson and Burr resolved by the House of Representatives

The Election of 1800 stands as a pivotal moment in American political history, not only for the clash between the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties but also for the unprecedented tie between Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr. This constitutional crisis, resolved by the House of Representatives, exposed vulnerabilities in the Electoral College system and set a precedent for future elections. At the heart of this drama were the two dominant political parties of the era: the Federalists, led by figures like John Adams, and the Democratic-Republicans, championed by Jefferson and Burr. Their ideological differences—Federalists favoring a strong central government and Democratic-Republicans advocating for states’ rights and agrarian interests—fueled the election’s intensity.

The tie itself was a product of the Electoral College’s design at the time, which did not distinguish between votes for president and vice president. Both Jefferson and Burr received 73 electoral votes, throwing the election into the House of Representatives, where each state delegation held a single vote. This process, outlined in the Constitution, became a battleground for political maneuvering. Federalists, who controlled the lame-duck Congress, initially sought to block Jefferson, whom they viewed as a radical threat to their vision of a centralized nation. Burr, though a Democratic-Republican, was seen by some as a more palatable alternative, adding layers of intrigue to the deadlock.

The resolution of the tie took 36 ballots over the course of a week, as state delegations grappled with their decisions. Alexander Hamilton, a Federalist with a deep-seated rivalry with Burr, played a surprising role by lobbying Federalists to support Jefferson, whom he considered the lesser of two evils. Hamilton’s influence proved decisive, and on February 17, 1801, Jefferson was elected president, with Burr becoming vice president. This outcome not only highlighted the flaws in the electoral system but also underscored the personal and ideological divisions within the young nation.

The Election of 1800 serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of partisan gridlock and the importance of clear electoral mechanisms. In response, the 12th Amendment was ratified in 1804, separating the votes for president and vice president and preventing similar ties in the future. This amendment remains a cornerstone of the U.S. electoral system, ensuring that such a crisis would not recur. The episode also illustrates the enduring impact of political parties, which continue to shape American elections and governance to this day.

For those studying or engaging with electoral history, the Election of 1800 offers practical lessons in constitutional interpretation and political strategy. It demonstrates how procedural ambiguities can lead to crises and how personal rivalries can influence national outcomes. Educators and students alike can draw parallels between this event and modern elections, analyzing how party dynamics and institutional design still play critical roles. By examining this pivotal moment, we gain insights into the resilience and adaptability of American democracy, even in the face of unprecedented challenges.

The Political Affiliation of the Top 1% Elite: Unveiling Party Ties

You may want to see also

Ideological Divide: Federalists favored elites; Democratic-Republicans championed common farmers and rural interests

The early 19th century in the United States was marked by a profound ideological divide between the two dominant political parties: the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. This rift was not merely a difference in policy but a clash of visions for the nation’s future. At the heart of this divide was the question of who should hold power and influence in the fledgling republic. The Federalists, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, advocated for a strong central government and aligned themselves with the interests of merchants, bankers, and urban elites. In contrast, the Democratic-Republicans, under the leadership of Thomas Jefferson, championed the rights of common farmers, rural communities, and the decentralized power of the states.

Consider the economic policies of these parties as a lens to understand their ideological differences. Federalists pushed for a national bank, tariffs to protect American industries, and a financial system that favored urban commercial interests. These policies were designed to consolidate economic power in the hands of a few, ensuring stability but at the cost of accessibility for the average citizen. Democratic-Republicans, however, viewed such measures as threats to individual liberty and rural livelihoods. They opposed the national bank, favored states’ rights, and promoted an agrarian economy, believing that the backbone of the nation lay in its farmers and rural communities.

To illustrate this divide, examine the contrasting views on the role of government. Federalists saw a strong central authority as essential for national unity and progress, often aligning with the wealthy and educated classes who benefited from such a system. Democratic-Republicans, on the other hand, feared centralized power as a precursor to tyranny and instead emphasized local control and the will of the majority. This ideological split was not just theoretical; it had tangible consequences, such as the Federalist support for the Alien and Sedition Acts, which restricted dissent, versus the Democratic-Republican push for the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, which asserted states’ rights to nullify federal laws.

Practical implications of this divide can be seen in the daily lives of early Americans. For instance, a farmer in rural Virginia would likely support Democratic-Republican policies that reduced federal interference and taxes, allowing him to retain more of his earnings. Conversely, a merchant in New York City might favor Federalist policies that protected his business from foreign competition and provided a stable financial system. These contrasting interests highlight how the ideological divide between the parties directly impacted the economic and social realities of different groups.

In conclusion, the ideological divide between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans in 1800 was a battle over the soul of the nation. Federalists sought to build a strong, centralized republic that favored elites, while Democratic-Republicans fought for a decentralized, agrarian society that prioritized the common man. This conflict was not merely about politics but about the fundamental values and future direction of the United States. Understanding this divide offers insight into the enduring tensions between centralized authority and individual liberty that continue to shape American politics today.

Exploring Las Vegas' Dominant Political Party and Its Local Influence

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The two main political parties in 1800 were the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson, and the Federalist Party, led by John Adams.

The Democratic-Republican Party was led by Thomas Jefferson, while the Federalist Party was led by John Adams.

The Democratic-Republican Party favored states' rights, a limited federal government, and agrarian interests, while the Federalist Party supported a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain.

The Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson, won the presidential election of 1800, defeating the incumbent Federalist President John Adams.