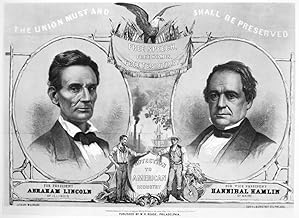

The 1860 United States presidential election was a pivotal moment in American history, marked by deep political and ideological divisions over slavery and states' rights. During this election, four major political parties vied for power, each representing distinct regional and ideological interests. The Democratic Party, split into Northern and Southern factions, nominated Stephen A. Douglas and John C. Breckinridge, respectively. The Republican Party, a relatively new force, nominated Abraham Lincoln on a platform opposing the expansion of slavery. The Constitutional Union Party, formed by former Whigs and Know-Nothings, nominated John Bell, advocating for preserving the Union without addressing slavery. Lastly, the Libertarian Party of the time, though not a formal party, represented abolitionist sentiments, though its influence was limited. These parties reflected the nation's fragmentation, setting the stage for the Civil War.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of Parties | 4 |

| Party Names | 1. Democratic Party 2. Republican Party 3. Constitutional Union Party 4. Southern Democratic Party |

| Key Issues | - Democratic Party: States' rights, slavery expansion - Republican Party: Opposition to slavery expansion - Constitutional Union Party: Preservation of the Union, avoiding secession - Southern Democratic Party: Secession, states' rights, slavery protection |

| Prominent Figures | - Democratic Party: Stephen A. Douglas - Republican Party: Abraham Lincoln - Constitutional Union Party: John Bell - Southern Democratic Party: John C. Breckinridge |

| Geographic Support | - Democratic Party: Northern and Southern Democrats - Republican Party: Primarily Northern states - Constitutional Union Party: Border states - Southern Democratic Party: Deep Southern states |

| Election Outcome (1860) | - Abraham Lincoln (Republican): Won the presidency - Stephen A. Douglas (Democratic): Second place - John C. Breckinridge (Southern Democratic): Third place - John Bell (Constitutional Union): Fourth place |

| Impact on Civil War | The election of Lincoln and the divide among these parties contributed to the secession of Southern states and the outbreak of the Civil War. |

Explore related products

$36.47 $49.99

What You'll Learn

- Democratic Party Split: Northern and Southern Democrats divided over slavery, nominating separate candidates

- Republican Party Rise: Abraham Lincoln’s party emerged opposing slavery expansion in territories

- Constitutional Union Party: Formed to avoid secession, focusing on preserving the Union

- Southern Democratic Party: Supported slavery, nominated John C. Breckinridge as candidate

- Key Issues of 1860: Slavery, states’ rights, and territorial expansion dominated political debates

Democratic Party Split: Northern and Southern Democrats divided over slavery, nominating separate candidates

The 1860 presidential election was a pivotal moment in American history, marked by deep divisions over slavery that fractured the political landscape. One of the most significant rifts occurred within the Democratic Party, where Northern and Southern Democrats could no longer reconcile their opposing views on slavery. This split led to the nomination of two separate candidates, Stephen A. Douglas in the North and John C. Breckinridge in the South, effectively dismantling the party’s unity and reshaping the election’s outcome.

To understand this division, consider the ideological chasm between the two factions. Northern Democrats, led by Douglas, embraced popular sovereignty—the idea that each territory should decide for itself whether to allow slavery. This stance, while pragmatic, failed to appease Southern Democrats, who demanded federal protection for slavery in all territories. Breckinridge and his supporters viewed Douglas’s position as a threat to the Southern way of life, insisting that slavery was a constitutional right that must be upheld nationally. This irreconcilable difference transformed a political disagreement into a full-blown party schism.

The practical consequences of this split were profound. By fielding two candidates, the Democrats fractured their voter base, allowing Abraham Lincoln, the Republican nominee, to win the presidency with only 39.8% of the popular vote. This outcome was a direct result of the Democrats’ inability to unite behind a single candidate, illustrating how internal divisions can lead to electoral defeat. For modern political parties, this serves as a cautionary tale: ideological purity can come at the cost of electoral viability.

A closer examination of the candidates themselves reveals the depth of the divide. Douglas, a skilled politician known for his debates with Lincoln, represented the moderate wing of the party, appealing to Northern voters who prioritized Union preservation over slavery expansion. Breckinridge, on the other hand, was a staunch defender of Southern interests, earning him the support of secessionists. Their competing nominations highlighted the party’s inability to bridge the gap between these two visions of America’s future.

In retrospect, the Democratic Party’s split in 1860 was not merely a political failure but a symptom of the nation’s broader moral and economic crisis. It underscored the incompatibility of Northern and Southern interests, setting the stage for the Civil War. For historians and political analysts, this event remains a critical case study in how single-issue disputes can dismantle even the most established institutions. The lesson is clear: in politics, unity is fragile, and its loss can have far-reaching consequences.

Ken Paxton's Political Affiliation: Unraveling His Party Ties

You may want to see also

Republican Party Rise: Abraham Lincoln’s party emerged opposing slavery expansion in territories

The 1860 presidential election was a pivotal moment in American history, marked by deep divisions over slavery and states' rights. Amid this turmoil, the Republican Party emerged as a formidable force, championing a platform that explicitly opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories. Led by Abraham Lincoln, the party’s rise was both strategic and ideological, leveraging growing Northern discontent with Southern dominance in national politics. While the Democratic Party fractured over the issue of slavery, the Republicans presented a unified front, appealing to a broad coalition of antislavery voters, economic modernizers, and those seeking a stronger federal government.

To understand the Republican Party’s ascent, consider its foundational principle: preventing the spread of slavery into the western territories. This stance was not abolitionist—the party did not seek to end slavery where it already existed—but it directly challenged the Southern economic system’s expansionist ambitions. Lincoln’s 1860 campaign framed this as a moral and economic imperative, arguing that free labor was superior to slave labor and that limiting slavery’s growth would preserve the Union. This message resonated in the North, where industrialization and wage labor were on the rise, and where many viewed slavery as a relic of the past.

The party’s organizational prowess played a critical role in its success. Republicans built a grassroots network that mobilized voters through newspapers, rallies, and local clubs. They also capitalized on the Democrats’ internal divisions, particularly after the collapse of the Whig Party and the emergence of the Constitutional Union Party, which further splintered the opposition. By contrast, the Republicans maintained discipline, rallying behind Lincoln despite his relative lack of national experience. This unity allowed them to win the presidency with just 39.8% of the popular vote, a testament to the electoral college’s role in amplifying regional majorities.

A key takeaway from the Republican Party’s rise is the power of a clear, focused message in a politically fragmented landscape. By centering their platform on a single, contentious issue—slavery expansion—they differentiated themselves from their opponents and galvanized a diverse base. This strategy not only secured Lincoln’s victory but also set the stage for the Civil War, as Southern states viewed the Republican agenda as an existential threat. For modern political movements, the lesson is clear: in times of polarization, a well-defined stance on a polarizing issue can be more effective than broad appeals to unity.

Practically, the Republican Party’s success offers a blueprint for building a political coalition. Start by identifying a core principle that resonates with your target audience, then develop a narrative that ties this principle to broader economic or social concerns. Invest in grassroots organizing to amplify your message and maintain party discipline to avoid internal fractures. Finally, recognize the importance of timing: the Republicans capitalized on a moment when their opponents were weak and divided, a tactic that remains relevant in today’s political arena. By studying their rise, we gain insights into how ideological clarity and strategic organization can shape the course of history.

Gerald Ford's Political Affiliation: Uncovering His Party Membership

You may want to see also

Constitutional Union Party: Formed to avoid secession, focusing on preserving the Union

In the tumultuous political landscape of 1860, the Constitutional Union Party emerged as a unique force, dedicated to a singular goal: preventing the secession of Southern states and preserving the Union. Unlike the other major parties of the time—the Republicans, Democrats, and Southern Democrats—the Constitutional Union Party did not advocate for specific policies on slavery or states' rights. Instead, its platform was deliberately vague, emphasizing adherence to the Constitution and the preservation of the Union above all else. This approach was both its strength and its weakness, as it sought to appeal to moderates in both the North and South but lacked the ideological clarity of its competitors.

The party's formation was a direct response to the deepening divide over slavery and secession. Its leaders, including former Whig politicians like John Bell, who became the party's presidential candidate, believed that focusing on constitutional principles could bridge the growing gap between the regions. The party's slogan, "The Constitution as it is, the Union as it is," encapsulated its mission. By avoiding contentious issues like the expansion of slavery, the Constitutional Union Party aimed to create a coalition of Unionists who prioritized national unity over sectional interests. However, this strategy also meant the party had little to offer in terms of concrete solutions to the nation's most pressing problems.

Analyzing the party's impact reveals its limitations. While it garnered significant support in border states like Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia, its inability to win a single electoral vote in the 1860 presidential election underscored its failure to unite the nation. The party's vague platform, though intended to appeal to a broad audience, ultimately left it without a strong identity. In a time of extreme polarization, its moderate stance was insufficient to counter the radical forces pulling the country apart. The Constitutional Union Party's brief existence highlights the challenges of maintaining unity through compromise in the face of irreconcilable differences.

From a practical standpoint, the Constitutional Union Party's approach offers a cautionary tale for modern political movements. While the desire to avoid divisive issues may seem appealing, it often results in a lack of direction and effectiveness. For those seeking to build consensus today, the lesson is clear: unity must be grounded in shared values and actionable goals, not merely the avoidance of conflict. The party's failure also reminds us that in times of crisis, vague appeals to tradition or stability are rarely enough to address deep-seated divisions. Instead, leaders must confront contentious issues head-on, offering clear and compelling solutions that resonate with a diverse electorate.

In conclusion, the Constitutional Union Party stands as a fascinating example of a political movement driven by the noble goal of preserving national unity. Its focus on the Constitution and the Union reflected a genuine desire to prevent the nation's fracture. However, its reluctance to engage with the underlying causes of secession ultimately rendered it ineffective. The party's story serves as a reminder that while compromise is essential in politics, it must be rooted in a clear vision and a willingness to address the root causes of division. For historians and political strategists alike, the Constitutional Union Party remains a compelling study in the complexities of maintaining a nation amidst crisis.

Discover Your Political Party: A Guide to Finding Your Political Home

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$27.95 $27.95

Southern Democratic Party: Supported slavery, nominated John C. Breckinridge as candidate

The 1860 presidential election was a pivotal moment in American history, marked by deep divisions over slavery and states' rights. Among the four major political parties, the Southern Democratic Party stood out for its unwavering support of slavery and its nomination of John C. Breckinridge as its candidate. This faction, which had split from the national Democratic Party, represented the interests of the Deep South and became a symbol of the growing rift between the North and South.

To understand the Southern Democratic Party’s stance, consider the context of the time. The national Democratic Party had failed to unite behind a single candidate, with Northern Democrats nominating Stephen A. Douglas and Southern Democrats breaking away to support Breckinridge. This split was primarily over the issue of slavery in the territories. While Douglas advocated for popular sovereignty, allowing territories to decide for themselves, Breckinridge and his supporters demanded federal protection of slavery in all territories, a non-negotiable position for Southern extremists.

Breckinridge’s nomination was a strategic move to solidify Southern control over the institution of slavery. A former Vice President under James Buchanan, Breckinridge was a Kentucky native who appealed to both border and Deep South states. His platform explicitly defended slavery as a constitutional right and condemned Northern attempts to restrict its expansion. This hardline stance resonated with Southern voters but alienated moderates, contributing to the party’s limited electoral success outside the South.

Analyzing the Southern Democratic Party’s strategy reveals its role in accelerating secession. By rejecting compromise and embracing a pro-slavery agenda, the party deepened regional polarization. Breckinridge’s campaign effectively served as a rallying cry for Southern secessionists, who viewed the election of Abraham Lincoln as a direct threat to their way of life. While Breckinridge carried most of the South, he finished second in the popular vote and third in the Electoral College, highlighting the party’s inability to win national support.

In retrospect, the Southern Democratic Party’s nomination of Breckinridge was both a symptom and a catalyst of the nation’s impending crisis. It exemplified the South’s commitment to slavery and its willingness to fracture the Union to preserve it. This chapter in political history underscores the dangers of extremism and the consequences of prioritizing regional interests over national unity. For modern readers, it serves as a cautionary tale about the fragility of democracy when fundamental values collide.

Discover Your Ideal Political Party: A Personalized Guide to Alignment

You may want to see also

Key Issues of 1860: Slavery, states’ rights, and territorial expansion dominated political debates

The 1860 presidential election unfolded against a backdrop of deep ideological divisions, with four major political parties vying for power: the Democratic Party, the Republican Party, the Constitutional Union Party, and the Southern Democratic Party. Each party’s platform reflected distinct stances on the era’s defining issues: slavery, states’ rights, and territorial expansion. These issues were not mere policy debates but existential questions that would shape the nation’s future.

Slavery stood as the most incendiary issue, pitting North against South. The Republican Party, led by Abraham Lincoln, advocated for halting slavery’s expansion into new territories, a position that Southern states viewed as a direct threat to their economic and social systems. The Southern Democrats, in contrast, demanded federal protection for slavery in all territories, reflecting their dependence on enslaved labor for agriculture. The Democrats, fractured by regional tensions, struggled to unify around a single candidate, ultimately nominating two: Stephen A. Douglas in the North and John C. Breckinridge in the South. Douglas supported popular sovereignty, allowing territories to decide on slavery, while Breckinridge championed its unrestricted expansion. The Constitutional Union Party, a coalition of former Whigs and moderate Democrats, avoided the issue altogether, prioritizing national unity over ideological purity.

States’ rights emerged as a corollary to the slavery debate, with Southern politicians arguing that the federal government had no authority to regulate slavery within individual states. This principle, rooted in the Tenth Amendment, became a rallying cry for secessionists who saw federal intervention as an assault on their autonomy. The Republicans countered that the Constitution granted Congress the power to regulate territories, setting the stage for a constitutional showdown. The issue was not merely legal but deeply emotional, as Southerners feared that Northern dominance would erode their way of life.

Territorial expansion further complicated the political landscape. The acquisition of new lands, such as those gained in the Mexican-Cession, raised questions about whether these territories would be slave or free. The Compromise of 1850 and the Dred Scott decision had temporarily eased tensions, but the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 reignited conflict by repealing the Missouri Compromise. Pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers clashed in "Bleeding Kansas," a microcosm of the national divide. The Republicans’ opposition to slavery in the territories appealed to Northern voters but alienated the South, where expansion was seen as vital to preserving the institution.

Practical considerations underscored these debates. For Southern planters, slavery was not just a moral issue but an economic necessity, as cotton production relied heavily on enslaved labor. Northern industrialists, meanwhile, viewed slavery as a barrier to wage labor and economic modernization. Voters in 1860 were not just choosing a president but deciding the moral and economic trajectory of the nation. The election’s outcome would determine whether the United States would remain a house divided or forge a new path toward unity and progress. Understanding these dynamics offers a lens into the complexities of American politics and the enduring legacy of the issues that defined 1860.

Councilwoman Lauren McNally's Political Party Affiliation Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The four major political parties in 1860 were the Democratic Party, the Republican Party, the Constitutional Union Party, and the Southern Democratic Party (also known as the National Democracy).

The Democratic Party and Southern Democratic Party supported states' rights and the expansion of slavery, while the Republican Party opposed the expansion of slavery. The Constitutional Union Party focused on preserving the Union and avoided taking a strong stance on slavery.

Abraham Lincoln represented the Republican Party, Stephen A. Douglas the Northern Democratic Party, John C. Breckinridge the Southern Democratic Party, and John Bell the Constitutional Union Party.