Citizens United v. FEC is a landmark case that addressed the constitutionality of restrictions on corporate spending in political campaigns. The case arose during the 2008 political primary season when Citizens United, a nonprofit corporation, sought to promote its political documentary Hillary: The Movie, which was critical of Hillary Clinton. The Federal Election Commission (FEC) found that Citizens United's plan to air television advertisements for the film violated the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA), which prohibited electioneering communications by corporations and labor unions within specific time frames before an election. Citizens United challenged the FEC's determination, arguing that the restrictions on independent political advertising and the disclosure requirements for such communications were unconstitutional under the First Amendment. The case ultimately reached the Supreme Court, which held that corporations have the same First Amendment speech rights as individuals, allowing unlimited corporate spending on campaign advertising as long as it is independent of a campaign or candidate. This ruling had significant implications for campaign finance, contributing to the rise of super PACs and increasing concerns about the influence of money in politics and the lack of transparency in election spending.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Year of ruling | 2010 |

| Case name | Citizens United v. FEC |

| Court | U.S. Supreme Court |

| Case type | Constitutional law |

| Area of law | Campaign finance, free speech |

| Lower court ruling | FEC's motion for summary judgment granted |

| Outcome | First Amendment protects corporate spending on political speech |

| Impact | Unlimited election spending by corporations, super PACs |

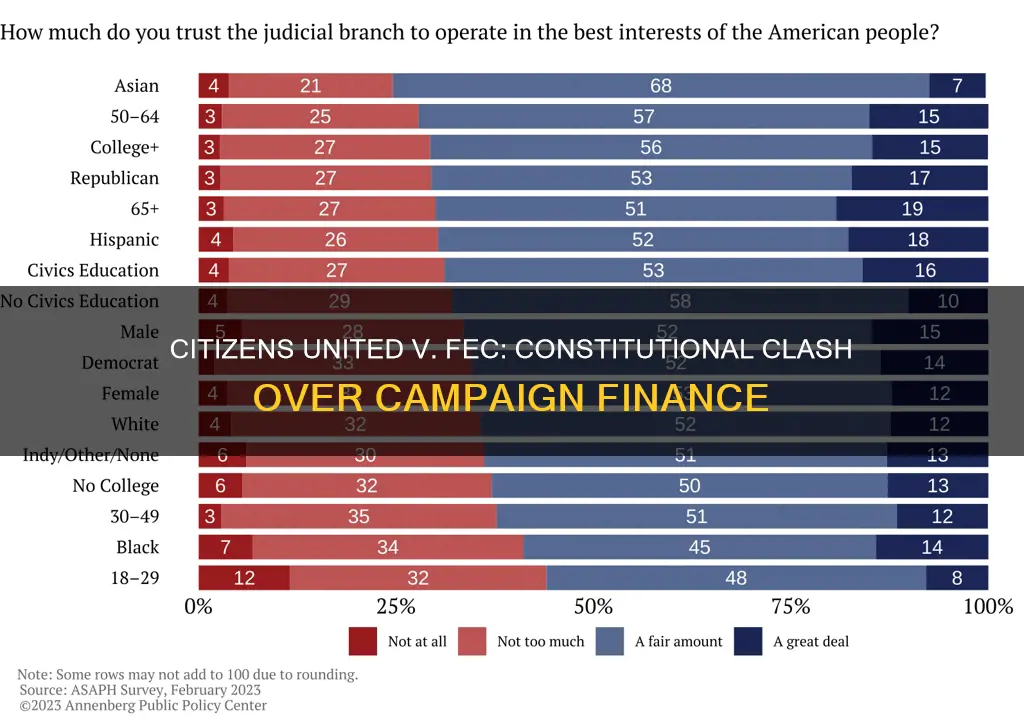

| Public opinion | Overwhelming disapproval |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The First Amendment and corporate personhood

The First Amendment to the US Constitution protects freedom of speech and freedom of the press, among other rights. The concept of "corporate personhood" refers to the ongoing legal debate over whether the rights traditionally associated with natural persons should also be afforded to juridical persons, including corporations.

The Supreme Court has affirmed the assumption of corporate personhood in several cases, including First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti (1978). In this case, the Court held that a Massachusetts law preventing corporations from spending money to promote their political views violated a corporation's First Amendment rights. The Court's ruling in Bellotti set the stage for subsequent cases, including Citizens United v. FEC.

In Citizens United v. FEC, the Supreme Court held that corporate funding of independent broadcasts of films about political subjects when there is an upcoming election cannot be limited under the First Amendment. This ruling allowed unlimited election spending by corporations and labor unions, setting a precedent for future cases involving corporate political spending.

The Citizens United ruling has been controversial and has sparked calls for a constitutional amendment to abolish corporate personhood. Critics argue that the ruling gives corporations too much influence in elections and allows them to pour vast amounts of money into political campaigns. Some also argue that granting legal fictions constitutional rights intended for humans is absurd, as corporations do not have minds or souls to hold beliefs or opinions.

Despite these criticisms, the concept of corporate personhood continues to evolve, with courts contemplating expanding corporate personhood to include First Amendment religious rights in cases like Sebelius v. Hobby Lobby Stores. The debate over corporate personhood highlights the complex nature of constitutional rights for corporations and the ongoing interpretation and application of the First Amendment in US law.

The Constitution's Surprising History: What You Didn't Know

You may want to see also

Disclosure and disclaimer requirements

In the case of Citizens United v. FEC, the constitutional issue centred on the regulation of political speech and spending by corporations and unions, specifically regarding "electioneering communications". Citizens United, a conservative nonprofit organization, challenged the Federal Election Commission's (FEC) interpretation and enforcement of certain statutory provisions governing disclaimers, disclosures, and funding restrictions on electioneering communications.

Citizens United's arguments against disclosure and disclaimer requirements:

- Unconstitutional Restriction: Citizens United argued that the disclosure and disclaimer requirements were unconstitutional when applied to their advertisements and all electioneering communications. They contended that the Supreme Court in WRTL narrowed the definition of "electioneering communication" to only include communications that are explicitly appeals to vote for or against a candidate. As their ads were not susceptible to such an interpretation, Citizens United asserted that they should not be subject to disclosure requirements.

- Commercial Speech Exemption: The organization also argued that the disclaimer requirements were unconstitutional as applied to their ads because commercial advertisements, including those promoting their film, should not be subject to disclaimers. They claimed that the government's interest in providing information to voters did not justify requiring disclaimers for commercial speech.

- Free Speech Concerns: Citizens United maintained that limiting independent expenditures by corporations and unions during political campaigns violated the First Amendment. They believed that such limitations constituted a prior restraint on speech and restricted the quantity and diversity of political expression.

Court rulings on disclosure and disclaimer requirements:

- District Court Rulings: The District Court denied Citizens United's motion for a preliminary injunction, finding that the suit was unlikely to succeed. The court held that the disclosure requirements were constitutional for all electioneering communications, citing the precedent set by McConnell v. FEC. Additionally, the court ruled that Citizens United's advertisements fell under the definition of "electioneering communication" and were subject to the corresponding restrictions.

- Supreme Court Decision: The Supreme Court agreed with Citizens United's broader argument that independent expenditures by corporations and unions were protected by the First Amendment. It held that speech was protected regardless of the speaker's corporate identity and that independent communications were not inherently corrupting. This interpretation allowed corporations and unions to spend unlimited funds on campaign advertising as long as they did not coordinate with a campaign or candidate directly.

The outcome of Citizens United v. FEC had significant implications for campaign finance regulations and transparency in political spending. It contributed to the rise of super PACs, which could accept unlimited contributions and spend substantial amounts on political advertisements without the same level of transparency as traditional campaign committees. The case highlighted the complex balance between free speech rights and the need for transparency and accountability in the electoral process.

Military Officers: Swearing Allegiance to the Constitution

You may want to see also

Corporate funding restrictions

In the case of Citizens United v. FEC, the issue of corporate funding restrictions was a key aspect of the constitutional debate. Citizens United, a nonprofit membership corporation, challenged the Federal Election Commission's (FEC) interpretation of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA), commonly known as the McCain-Feingold Act.

Citizens United's argument centred on the definition of "electioneering communications" and the restrictions on corporate funding for such communications. They contended that certain forms of communication, such as advertisements and films, should not be subject to the same restrictions as direct political advertising. Specifically, they argued that the EC disclosure and disclaimer requirements were unconstitutional and that the film "Hillary: The Movie" was constitutionally exempt from corporate funding restrictions.

The FEC, on the other hand, maintained that Citizens United's planned advertisements for "Hillary: The Movie" during the 2008 political primary season violated the BCRA. According to Section 203 of the BCRA, an "electioneering communication" included mentions of a candidate within 60 days of a general election or 30 days of a primary, and prohibited expenditures by corporations and labour unions. The FEC's interpretation of the law led to a ban on the film's broadcast, which Citizens United challenged in court.

The District Court denied Citizens United's motion for a preliminary injunction, finding that the film constituted express advocacy and was not entitled to exemption from the ban on corporate funding. This decision was based on the precedent set by the Supreme Court in McConnell v. FEC, which upheld the constitutionality of disclosure requirements for all electioneering communications. However, Citizens United continued to pursue the case, arguing for their First Amendment rights to free speech and challenging the restrictions on independent expenditures by corporations.

The outcome of Citizens United v. FEC had significant implications for campaign finance regulations. The ruling allowed unlimited election spending by corporations and labour unions, setting a precedent for future cases like Speechnow.org v. FEC, which authorized the creation of super PACs. This contributed to a surge in secret spending and increased the influence of wealthy donors and dark money groups in politics, leading to widespread disapproval and calls for constitutional amendments to overturn the decision.

Understanding Constitutional Crises in the United States

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Definition of electioneering communication

The case of Citizens United v. FEC centred on the issue of free speech and the regulation of political advertising by corporations, specifically in the context of "electioneering communications".

An "electioneering communication" is defined by the Federal Election Commission (FEC) as any broadcast, cable, or satellite communication that refers to a clearly identified federal candidate and is publicly distributed within specific time frames: 30 days before a primary election or 60 days before a general election. The communication must also be targeted to the relevant electorate or voters. This definition was outlined in the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA), also known as the McCain-Feingold Act, which was enacted in 2002.

The BCRA prohibits corporations and labour unions from making independent expenditures on electioneering communications. In other words, these entities are not allowed to air political advertisements that mention a candidate within the specified time frames before an election. This restriction was challenged by Citizens United, a nonprofit membership corporation, which argued that the EC disclosure and disclaimer requirements were unconstitutional.

To be considered "publicly distributed", the communication must be aired, broadcast, cablecast, or otherwise disseminated through radio, television, cable television, or satellite systems. A candidate is "clearly identified" if their name, nickname, photograph, or drawing is used, or if their identity is apparent through an unambiguous reference, such as "the President" or "your Representative".

It's important to note that there are exemptions to what constitutes an electioneering communication. For example, bona fide news stories that are part of a general pattern of campaign-related news accounts giving equal coverage to all opposing candidates are not considered electioneering communications. Additionally, communications funded by a candidate for nonfederal office in connection with a nonfederal election are not considered electioneering if they do not promote or oppose any federal candidate.

The Constitution's Core Objectives Explained

You may want to see also

The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act

The law became effective on November 6, 2002, and the new legal limits became effective on January 1, 2003. The Act was designed to address two issues: the increased role of soft money in campaign financing and the proliferation of issue advocacy ads.

Firstly, the BCRA prohibited national political party committees from raising or spending any funds not subject to federal limits, even for state and local races or issue discussion. This included limiting soft money spending for federal election activities by state, district, and local political party committees, as well as associations or similar groups of candidates for state or local office. It also required disclosure by state and local parties of spending on federal election activities, including any soft money used.

Secondly, the BCRA defined "electioneering communications" as broadcast ads that mentioned a federal candidate within 30 days of a primary or caucus or 60 days of a general election. It prohibited any such ad paid for by a corporation (including non-profit issue organizations) or paid for by an unincorporated entity using any corporate or union general treasury funds.

In 2022, the Supreme Court also struck down Section 304 of the BCRA, which limited the monetary amount of post-election contributions a candidate could use to pay back personal campaign loans, finding that it impermissibly limited political speech and violated the First Amendment.

Understanding Good Cause for Quitting in Massachusetts

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Citizens United, a conservative nonprofit organisation, wanted to promote its political documentary 'Hillary: The Movie' during the 2008 political primary season. The Federal Election Commission (FEC) found this to be in violation of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA), which prohibits "electioneering communications" by incorporated entities. Citizens United challenged this in court, arguing that the BCRA's restrictions on independent political advertising were unconstitutional.

The constitutional issue in Citizens United v. FEC centred around the First Amendment, which protects free speech. Citizens United argued that the BCRA's restrictions on independent expenditures and corporate funding of electioneering communications violated their right to free speech. They claimed that speech should be protected regardless of the speaker's corporate identity and that independent communications are not inherently corrupting.

The Supreme Court ruled in favour of Citizens United, holding that the First Amendment provides the same speech rights for corporations as for individuals. This ruling interpreted the First Amendment to allow corporations to spend unlimited funds on campaign advertising, as long as they do not coordinate with a campaign or candidate. The Court found that limiting independent expenditures by corporations and other groups violated the First Amendment as it constituted a prior restraint on speech.

The Citizens United ruling had a significant impact on campaign finance law and contributed to a major increase in political spending. It allowed unlimited election spending by corporations and labour unions, setting the stage for the creation of "super PACs", which can accept unlimited contributions and spend unlimited amounts on elections without having to directly coordinate with candidates. The ruling also contributed to a lack of transparency in political spending, making it difficult to track the original source of donations.