The US Constitution of 1787, which was ratified in 1788, addressed the issue of slavery in several ways, but never mentioned the word itself. The Constitution's provisions regarding slavery were the product of a series of conflicts, accommodations, and compromises. While it did not make the US a slaveholders' republic, it also failed to explicitly define slaves as property or identify slavery as a race-based condition. The Constitution recognised the existence of slavery as a powerful sectional interest and granted slaveholders important privileges, such as the three-fifths clause, the African slave trade clause, and the fugitive slave clause. The question of whether the Constitution was pro-slavery or anti-slavery remains a subject of debate.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date | 17 August 1787 |

| Location | Philadelphia |

| Number of Delegates | 55 |

| Nature of Constitution | Neither wholly anti-slavery nor wholly pro-slavery |

| Mention of "Slave" or "Slavery" | No |

| Three-Fifths Clause | Yes |

| Fugitive Slave Clause | Yes |

| Slave Trade Clause | Yes |

| Compromise | Slave trade would be allowed until 1808, but could be taxed |

| Bill of Rights | No |

| Central Government | Powerful enough to eventually abolish slavery |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- The Constitution of 1787 neither wholly supported nor condemned slavery

- The Constitution's three-fifths clause gave Southern states more power

- The Constitution's fugitive slave clause was pro-slavery

- The Constitution's slave trade clause prohibited banning the slave trade until 1808

- The Constitution's authors avoided using the words 'slave' or 'slavery'

The Constitution of 1787 neither wholly supported nor condemned slavery

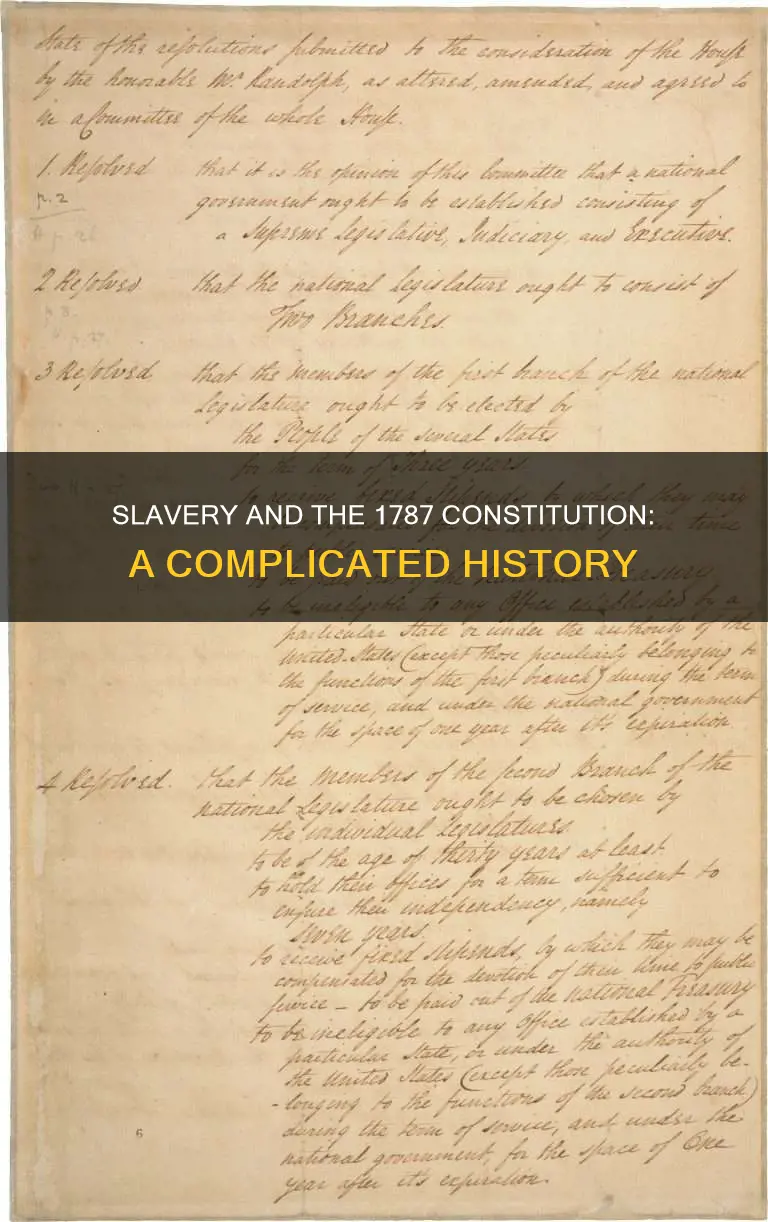

The Constitution of 1787, like nearly every other significant outcome of the American Revolution, was the result of prolonged and contentious conflict, debate, and accommodation. The Constitution neither wholly supported nor condemned slavery.

The Constitution addressed the issue of slavery in several ways but never mentioned the word itself. The three clauses that most directly addressed slavery were the so-called three-fifths clause, the African slave trade clause, and the fugitive slave clause. The three-fifths clause counted three-fifths of each state's slave population towards that state's total population for the purpose of apportioning the House of Representatives, giving the Southern states more power in the House and in the Electoral College. The African slave trade clause prohibited Congress from banning the importation of slaves until 1808. The fugitive slave clause stated that any person held to service or labour in one state who escaped to another state would be returned to their original owner.

The Constitution also failed to explicitly define slaves as property or identify slavery as a race-based condition. It deferred to normal political processes the manner in which the federal government would use its powers regarding slavery. This meant that even if the government wanted to act against slavery, it would have to go through the normal political channels of passing a bill through Congress and having it signed into law by the president.

The framers of the Constitution had conflicting views on slavery, and this is reflected in the final document. Some saw it as an example of systemic racism at the core of America's founding, while others pointed to the efforts of slavery's opponents to limit its sphere of influence to the Southern states, with the hope that all states would eventually abolish it. While the Constitution did not create a slaveholders' republic, it recognised the existence of slavery as a powerful sectional interest and granted slaveholders important privileges.

US and Florida Constitutions: Similarities and Shared Values

You may want to see also

The Constitution's three-fifths clause gave Southern states more power

The US Constitution, which was adopted in 1787, addressed the issue of slavery in several ways, but the word "slavery" was never mentioned. The three-fifths clause, the African slave trade clause, and the fugitive slave clause were the most direct examples of this. The three-fifths clause, also known as the Three-Fifths Compromise, counted three-fifths of each state's slave population toward that state's total population for the purpose of apportioning the House of Representatives. This gave the Southern states more power in the House relative to the Northern states.

The Three-Fifths Compromise was struck to resolve the impasse between slaveholding states and free states. Slaveholding states wanted their entire population to be counted to determine the number of Representatives they could send to Congress, while free states wanted to exclude the counting of slave populations in slave states, as those slaves had no voting rights. The compromise effectively gave slaveholders enlarged powers in Southern legislatures and contributed to the secession of West Virginia from Virginia in 1863.

The three-fifths ratio originated with an amendment proposed to the Articles of Confederation on April 18, 1783. The amendment changed the basis for determining a state's wealth, and hence its tax obligations, from real estate to population. This was seen as a measure of a state's ability to produce wealth. The proposal suggested that taxes "be supplied by the several colonies in proportion to the number of inhabitants of every age, sex, and quality, except Indians not paying taxes".

The Three-Fifths Compromise has been interpreted in different ways by historians, legal scholars, and political scientists. Some argue that it supported the notion that slaves were conceived of as only three-fifths of a person, while others believe that the three-fifths ratio was purely a statistical designation used to determine the number of representatives for Southern states. The debate over the interpretation of the Three-Fifths Compromise illustrates the complex and contentious nature of the issue of slavery in the context of the US Constitution.

Overall, the Constitution of 1787 recognized the existence of slavery as a powerful sectional interest and granted slaveholders important privileges. It stopped short of making the United States a slaveholders' republic, but it also failed to explicitly define slaves as property or identify slavery as a race-based condition. The Constitution's provisions regarding slavery were the result of a series of conflicts, accommodations, and compromises between opposing factions.

The Significance of the US Constitution's Signing Day

You may want to see also

The Constitution's fugitive slave clause was pro-slavery

The US Constitution, adopted in 1787, addressed the issue of slavery in several ways, including the Fugitive Slave Clause, but never mentioned the word "slavery" itself. The Fugitive Slave Clause, also known as the Slave Clause or the Fugitives From Labour Clause, was part of Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3 of the US Constitution. It required that a "Person held to Service or Labour" who escaped to another state be returned to their master in the state from which they fled.

The wording of the clause was carefully crafted to avoid overtly validating slavery at the federal level. The phrase legally held to service or labour in one state was changed to "held to service or labour in one state, under the laws thereof." This revision made it impossible to interpret the Constitution as legally sanctioning slavery. The ambiguity of the clause allowed both pro- and anti-slavery factions to claim constitutional ground, reflecting the contradictions in the founding document.

The Fugitive Slave Clause gave slaveholders the right to capture enslaved persons who ran away and formed the basis for the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. This Act was enforced by the extradition clause, which regulated interstate extraditions. The Fugitive Slave Clause remained in full effect until the abolition of slavery under the Thirteenth Amendment, which made the clause unenforceable.

The inclusion of the Fugitive Slave Clause in the US Constitution can be interpreted as pro-slavery. It provided a constitutional right for enslavers to recover enslaved persons who escaped to another state. This clause was a significant tool for slaveholders to maintain their power and control over enslaved persons, even if they fled to a free state. The clause's enforcement through the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 further highlights its pro-slavery nature, as it facilitated the capture and return of fugitive slaves to their masters.

The New Jersey Plan: Constitution's Foundation and Framing

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$29.99 $37.99

The Constitution's slave trade clause prohibited banning the slave trade until 1808

The Constitution of 1787 was a product of prolonged and contentious conflict, debate, and accommodation. The provisions regarding slavery were no exception, with voters, politicians, and delegates from both sections failing to obtain all that they might have sought. The Constitution recognised the existence of slavery as a powerful sectional interest and granted slaveholders important privileges.

One of the most significant ways the Constitution addressed slavery was through the Slave Trade Clause, also known as Article 1, Section 9, Clause 1. This clause prohibited the federal government from banning the importation of "persons" (which at the time was understood to mean primarily enslaved African persons) until 20 years after the Constitution took effect, or until 1808. This was a compromise between the Southern states, where slavery was pivotal to the economy, and the Northern states, where abolition was contemplated or had already been accomplished.

The Slave Trade Clause's wording, "importations of such persons", was a euphemism for the slave trade, which the draft Constitution allowed to continue indefinitely and forbade the United States Congress from ever taxing or prohibiting before 1808. This clause was a compromise between those who wanted to ban the slave trade immediately and those who wanted to protect it. By delaying the potential ban until 1808, the delegates hoped to increase the chances of the Constitution being adopted, as some Southern states may have refused to ratify it if Congress could ban the slave trade.

In the years leading up to 1808, popular support for the abolition of the slave trade and slavery itself grew both within the United States and internationally. Congress passed statutes in the 1790s regulating the trade in slaves by U.S. ships on the high seas, and in 1794, the Slave Trade Act ended the legality of American ships participating in the trade. In 1806, President Thomas Jefferson called for the upcoming expiration of Article 1, Section 9, Clause 1, and in March 1807, Congress passed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves, which took effect on January 1, 1808, the earliest date permitted by the Constitution.

The Constitution: Power to the People

You may want to see also

The Constitution's authors avoided using the words 'slave' or 'slavery'

The US Constitution of 1787 addressed the issue of slavery in several ways, but the word "slave" does not appear in the document. Instead, the Constitution refers to "such persons" or persons held to service or labour. The authors of the Constitution consciously avoided using the word "slave", recognising that it would sully the document.

The three clauses that most directly addressed slavery were the three-fifths clause, the African slave trade clause, and the fugitive slave clause. The three-fifths clause counted three-fifths of a state's slave population when apportioning representation, giving the South extra representation in the House of Representatives and extra votes in the Electoral College. The African slave trade clause, or Article 1, prohibited Congress from banning the slave trade until 1808. The fugitive slave clause, or Article 4, required that any person held to service or labour in one state who escaped to another must be returned to the person to whom their service was due.

The Constitution also failed to explicitly define slaves as property or identify slavery as a race-based condition. It recognised the existence of slavery as a powerful sectional interest and granted slaveholders important privileges. However, it did not make the United States a slaveholders' republic, as was the case in the Southern states. Instead, it deferred to normal political processes the manner in which the federal government would use its powers regarding slavery.

The Constitution of 1787 was the product of prolonged and contentious conflict, debate, and accommodation. Many of the framers harboured moral qualms about slavery, and some became members of anti-slavery societies. However, about 25 of the 55 delegates to the Constitutional Convention owned slaves. The question of whether the Constitution was a pro-slavery document remains controversial. While it temporarily strengthened slavery, it also created a central government powerful enough to eventually abolish the institution.

US Constitution: Can We Lose Confidence?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Constitution of 1787 is the original US Constitution, which was adopted in Philadelphia in September 1787 and ratified in the spring of 1788.

Yes, the Constitution of 1787 addressed the issue of slavery in several ways, but the word "slavery" was never mentioned.

The three most direct clauses related to slavery in the Constitution of 1787 were the Three-Fifths Clause, the Slave Trade Clause, and the Fugitive Slave Clause.

The Three-Fifths Clause counted three-fifths of each state's slave population towards that state's total population for the purpose of apportioning the House of Representatives, giving the Southern states more power in the House and in the Electoral College.

The Fugitive Slave Clause, which was part of Article IV, stated that any person held to service or labour in one state who escaped to another state would be returned to the original state. This clause has been interpreted as a pro-slavery measure that protected the interests of slaveholders.