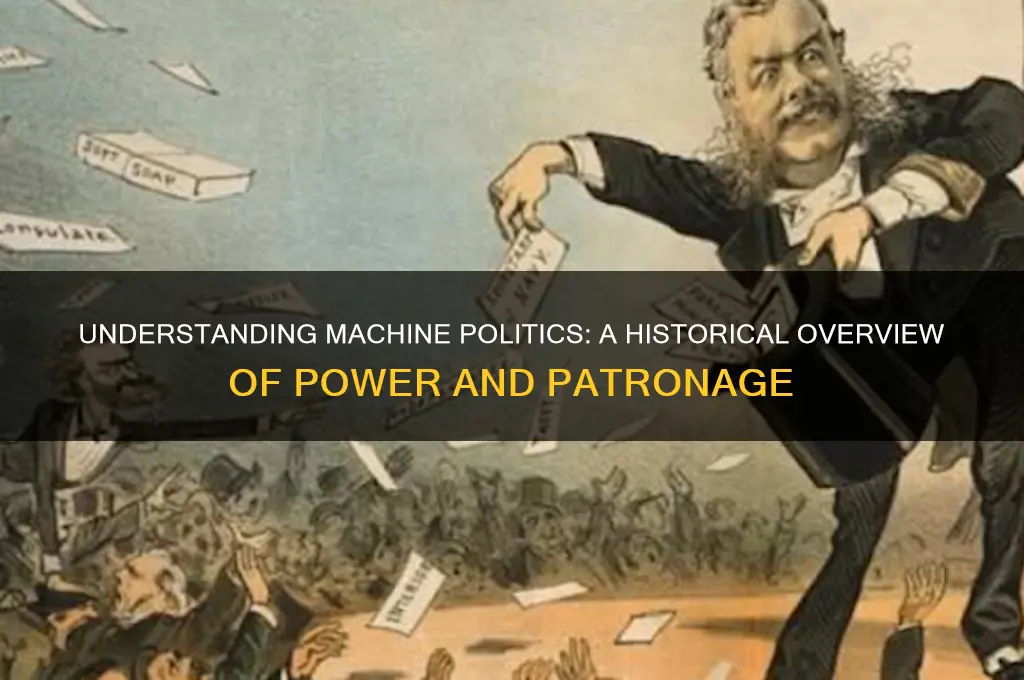

Machine politics, prevalent in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, refers to a system of political organization where party bosses controlled local and municipal governments through patronage, corruption, and voter mobilization. These political machines operated by exchanging favors, jobs, and services for votes, often leveraging immigrant communities and working-class neighborhoods. While they provided social services and support to marginalized groups, they were also notorious for graft, fraud, and the consolidation of power in the hands of a few. Notable examples include Tammany Hall in New York City, which epitomized the machine politics model. Despite their decline due to reforms and public backlash, machine politics left a lasting impact on American political history, shaping urban governance and the relationship between citizens and their leaders.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Patronage System | Distribution of government jobs, contracts, and favors to loyal supporters. |

| Strong Central Leadership | Dominance of a single leader or boss who controls the organization. |

| Grassroots Mobilization | Extensive network of local operatives to mobilize voters and resources. |

| Quid Pro Quo Relationships | Exchange of political support for tangible benefits (e.g., jobs, services). |

| Control Over Local Government | Dominance in city or municipal politics, often through elected officials. |

| Voter Turnout Manipulation | Use of tactics like voter intimidation, fraud, or incentives to sway elections. |

| Clientelism | Provision of services or resources to specific groups in exchange for loyalty. |

| Lack of Transparency | Opaque decision-making processes and hidden deals. |

| Long-Term Dominance | Sustained control over political institutions for extended periods. |

| Use of Resources for Power | Leveraging public resources (e.g., funds, infrastructure) to maintain influence. |

| Resistance to Reform | Opposition to changes that threaten the machine's power structure. |

| Ethnic or Community Ties | Often rooted in specific ethnic, racial, or community groups for support. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Boss-led systems: Powerful leaders controlled political machines, often dictating policies and appointments

- Patronage networks: Jobs and favors were exchanged for votes and loyalty

- Urban dominance: Machines thrived in cities, managing local politics and services

- Voter mobilization: Machines used tactics like canvassing and turnout drives to win elections

- Corruption and reform: Machines often faced scrutiny for graft, leading to reform movements

Boss-led systems: Powerful leaders controlled political machines, often dictating policies and appointments

In the annals of political history, the term "boss-led systems" evokes images of powerful figures who wielded immense control over the machinery of governance. These political bosses were the architects of machine politics, a phenomenon that dominated urban American politics during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. At the heart of this system was a simple yet effective strategy: centralized power in the hands of a single leader, often referred to as the "boss," who dictated policies, controlled appointments, and ensured the loyalty of the political machine's cogs.

Consider the case of Boss Tweed, the notorious leader of Tammany Hall in New York City. Tweed's reign exemplified the boss-led system, where his word was law within the Democratic Party's local apparatus. He handpicked candidates for various offices, from judges to aldermen, ensuring their loyalty through patronage and favors. This top-down approach allowed Tweed to shape policies that benefited his allies and punished his opponents, often with little regard for the public good. The boss's power was absolute, and his influence permeated every level of government, from city hall to the state legislature.

The mechanics of a boss-led system can be broken down into a series of strategic steps. First, the boss establishes a strong personal network, cultivating relationships with key stakeholders, including business leaders, labor unions, and community organizers. This network becomes the foundation of the political machine, providing resources, votes, and influence. Second, the boss consolidates power by controlling access to government jobs, contracts, and services, rewarding loyalists and punishing dissenters. This patronage system ensures compliance and discourages defections. Finally, the boss dictates policies and appointments, using his influence to shape legislation, allocate resources, and appoint officials who will further his agenda.

However, the boss-led system is not without its pitfalls. The concentration of power in a single individual can lead to corruption, as seen in the Tweed Ring's infamous graft and bribery scandals. Moreover, the system's reliance on patronage can stifle meritocracy, as appointments are based on loyalty rather than competence. To mitigate these risks, modern political systems have implemented checks and balances, such as term limits, campaign finance regulations, and independent oversight bodies. For instance, the introduction of civil service reforms in the late 19th century aimed to replace patronage-based appointments with competitive examinations, ensuring that government jobs were awarded based on merit rather than political connections.

In conclusion, the boss-led system was a defining feature of machine politics, characterized by the centralized control of a powerful leader. While this approach allowed for efficient decision-making and policy implementation, it also carried significant risks, including corruption and the erosion of democratic principles. By examining the historical examples and mechanics of boss-led systems, we can gain valuable insights into the importance of transparency, accountability, and decentralization in modern governance. As a practical tip, citizens can stay informed about local politics, engage with their representatives, and advocate for reforms that promote ethical leadership and equitable representation, thereby reducing the likelihood of boss-led systems re-emerging in contemporary politics.

Frankenstein's Political Undercurrents: Power, Responsibility, and Social Rebellion

You may want to see also

Patronage networks: Jobs and favors were exchanged for votes and loyalty

Patronage networks were the lifeblood of machine politics, a system where political power was consolidated through a delicate balance of reciprocity. At its core, this system thrived on a simple exchange: jobs and favors for votes and unwavering loyalty. This transactional relationship formed the backbone of political machines, particularly in urban areas during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For instance, in Tammany Hall, the Democratic Party machine in New York City, party bosses like Boss Tweed wielded immense influence by controlling access to government jobs, contracts, and services, ensuring a steady stream of support from constituents.

Consider the mechanics of this system: a party boss would appoint loyalists to government positions, from clerks to police officers, in exchange for their commitment to deliver votes during elections. These appointees, in turn, would mobilize their communities, often using their influence to sway neighbors, friends, and family. Favors, such as assistance with immigration paperwork, housing, or even legal troubles, were dispensed to solidify loyalty. This network of mutual benefit created a self-sustaining ecosystem where political survival depended on maintaining these intricate webs of obligation.

However, the effectiveness of patronage networks was not without its pitfalls. Critics argue that such systems often prioritized loyalty over competence, leading to inefficiency and corruption. For example, unqualified individuals might be appointed to critical roles simply because they were part of the machine, undermining public trust in government institutions. Moreover, the reliance on patronage could stifle political competition, as challengers struggled to break through the entrenched networks of established machines.

To understand the enduring legacy of patronage networks, examine their modern equivalents. While overt political machines have largely faded, elements of this system persist in the form of campaign contributions, endorsements, and strategic appointments. For instance, politicians today still reward supporters with ambassadorships or advisory roles, echoing the patronage model of yesteryears. This continuity highlights the enduring appeal of reciprocal relationships in politics, even as societal norms and legal frameworks have evolved to curb abuses.

In practical terms, recognizing the dynamics of patronage networks can offer insights into contemporary political behavior. For activists or reformers, understanding this system underscores the importance of transparency and accountability in governance. By dismantling opaque structures and promoting merit-based appointments, it is possible to mitigate the negative aspects of patronage while preserving its potential for community engagement. Ultimately, the study of patronage networks serves as a reminder that politics, at its core, is often about relationships—and the currency of those relationships is trust, loyalty, and mutual benefit.

The Olympics and Politics: A Complex Global Intersection Explored

You may want to see also

Urban dominance: Machines thrived in cities, managing local politics and services

Machine politics, a phenomenon predominantly rooted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, found its most fertile ground in urban environments. Cities, with their dense populations, diverse demographics, and complex social structures, provided the ideal ecosystem for political machines to flourish. These organizations, often tied to a particular political party, exerted control over local politics and services through a combination of patronage, clientelism, and strategic resource allocation. The urban landscape, with its myriad needs and vulnerabilities, became the playground for machine bosses who mastered the art of delivering tangible benefits in exchange for political loyalty.

Consider the mechanics of how machines operated in cities like New York, Chicago, or Philadelphia. They thrived by addressing the immediate needs of urban dwellers, particularly immigrants and the working class, who often felt neglected by mainstream political institutions. Machines provided jobs, housing, and even basic necessities like coal for heating during harsh winters. For instance, Tammany Hall in New York City became legendary for its ability to mobilize voters by offering assistance with citizenship papers or legal aid. This transactional approach created a symbiotic relationship: citizens received essential services, while machine bosses secured votes and political power. The efficiency of this system was undeniable, though it often came at the cost of transparency and accountability.

The dominance of machines in urban areas was also a product of their ability to navigate the complexities of city governance. Local politics in cities involved managing a wide array of services, from sanitation and transportation to education and public safety. Machines streamlined these processes by centralizing control and ensuring that resources were distributed in ways that reinforced their political hold. For example, in Chicago, the Democratic machine under figures like Anton Cermak and Richard J. Daley wielded immense influence over city contracts, zoning decisions, and public works projects. This control not only solidified their power but also allowed them to reward allies and punish opponents, creating a system that was both efficient and coercive.

However, the urban dominance of machines was not without its drawbacks. While they provided immediate solutions to pressing urban problems, their methods often perpetuated corruption and inequality. Patronage jobs, for instance, were frequently awarded based on political loyalty rather than merit, leading to inefficiencies in public services. Moreover, the focus on short-term gains sometimes overshadowed long-term urban planning and development. Critics argue that this approach stifled innovation and entrenched systemic issues like poverty and inadequate infrastructure. Despite these flaws, the legacy of machine politics in cities remains a testament to the power of localized, service-oriented governance.

To understand the enduring impact of machine politics, one must examine how its principles have evolved in modern urban governance. While overt patronage systems have largely been dismantled, echoes of machine-style politics persist in the way local leaders mobilize resources and build coalitions. For instance, community-based organizations often play a role similar to that of machines, providing services and advocacy in exchange for political support. The lesson here is clear: in cities, where needs are immediate and resources are finite, the ability to deliver tangible benefits remains a cornerstone of political influence. Whether viewed as a necessary evil or a pragmatic solution, the urban dominance of machines highlights the intricate relationship between power, service, and loyalty in local politics.

Decoding the Political Compass: A Beginner's Guide to Understanding Ideologies

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Voter mobilization: Machines used tactics like canvassing and turnout drives to win elections

Machine politics thrived on the ability to deliver votes, and voter mobilization was its lifeblood. Canvassing, a door-to-door strategy, was a cornerstone tactic. Machine operatives, often local ward heelers, would systematically visit households, identifying supporters, addressing concerns, and offering incentives for turnout. This personalized approach fostered a sense of obligation and loyalty, ensuring voters felt seen and heard by the machine. For example, Tammany Hall in New York City famously deployed armies of canvassers who not only reminded voters of election day but also provided transportation, childcare, and even meals to remove any barriers to voting.

Canvassing wasn’t just about reminders; it was about building relationships. Machines understood that elections were won not just by policies but by personal connections. By addressing individual needs and fostering a sense of community, machines created a network of dependable voters who turned out reliably, election after election.

Turnout drives, another key tactic, were large-scale, high-energy events designed to generate momentum and excitement. These drives often involved parades, rallies, and speeches, transforming voting into a communal celebration. Machines would distribute campaign literature, buttons, and banners, creating a visual spectacle that reinforced their dominance. In Chicago during the early 20th century, Democratic machines organized massive turnout drives that included free food, live music, and even cash incentives for voters. These events weren’t just about mobilizing supporters; they were about intimidating opponents by showcasing the machine’s strength and popularity.

The effectiveness of these tactics lay in their combination of personalization and scale. While canvassing targeted individuals, turnout drives created a collective identity, making voters feel part of something larger than themselves. Machines understood that voting wasn’t just a civic duty; it was a social act. By blending these strategies, they ensured high turnout among their base, often tipping the balance in close elections.

However, these methods weren’t without ethical concerns. Critics argued that machines exploited vulnerabilities, particularly among impoverished or less educated voters, by offering material incentives. The line between encouragement and coercion was often blurred, raising questions about the integrity of the electoral process. Despite these criticisms, the success of machine politics in mobilizing voters cannot be denied. Their tactics, though controversial, offer valuable lessons in understanding the psychology of voter behavior and the importance of grassroots engagement in winning elections.

Can 501(c)(3) Nonprofits Engage in Political Activities? Exploring the Limits

You may want to see also

Corruption and reform: Machines often faced scrutiny for graft, leading to reform movements

Machine politics, a system where political parties wielded power through patronage and control of local government, often thrived on a delicate balance of favors and loyalty. However, this system was inherently susceptible to corruption, as the line between political influence and personal gain blurred. Graft, the misuse of public funds or resources for private benefit, became a hallmark of many political machines, sparking widespread public outrage and fueling reform movements.

Consider the Tammany Hall machine in New York City during the 19th century. Led by figures like Boss Tweed, Tammany Hall controlled city politics through a network of patronage jobs and favors. While it provided services to immigrants and the poor, it also engaged in massive embezzlement, with millions of dollars siphoned from public projects like the construction of the Tweed Courthouse. The exposure of this corruption, notably through the investigative journalism of *The New York Times* and the cartoons of Thomas Nast, galvanized public opinion and led to Tweed’s downfall and the eventual decline of Tammany Hall’s dominance.

Reform movements emerged as a direct response to such abuses, often spearheaded by middle-class activists and progressive politicians. The Progressive Era (1890s–1920s) saw the rise of initiatives like civil service reform, which aimed to replace patronage-based hiring with merit-based systems. For instance, the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883 introduced competitive exams for federal jobs, reducing the influence of political machines. Similarly, the direct primary system and the secret ballot diminished machine control over elections, empowering individual voters.

Yet, reform was not without challenges. Machines often adapted to new rules, finding loopholes or shifting their tactics. For example, while civil service reforms limited patronage appointments, machines continued to exert influence through control of local contracts and favors. This cat-and-mouse game between machines and reformers highlights the resilience of such systems and the need for sustained vigilance.

In practical terms, combating machine corruption requires a multi-pronged approach. Strengthening transparency through open records laws and independent audits can deter graft. Empowering investigative journalism and whistleblowers provides a critical check on abuses. Finally, fostering civic engagement ensures that reform efforts are not merely top-down but rooted in community demands for accountability. The legacy of machine politics reminds us that democracy’s health depends on constant scrutiny and active participation.

Mastering Polite Greetings: Tips for Warm and Respectful First Impressions

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Machine politics refers to a system of political organization where a centralized group, often led by a powerful boss, controls political activities, patronage, and resources in exchange for votes and loyalty.

Machine politics operated by providing services like jobs, housing, and assistance to immigrants and the poor in exchange for their votes, creating a network of dependency and control.

Political bosses were the leaders of these machines, distributing patronage, managing elections, and ensuring their party’s dominance by controlling local government and resources.

Machine politics was most prominent in large urban areas like New York City, Chicago, and Boston, where immigrant populations relied on political machines for support.

The decline of machine politics was driven by reforms like the introduction of civil service systems, direct primaries, and anti-corruption laws, which reduced the influence of political bosses and patronage networks.