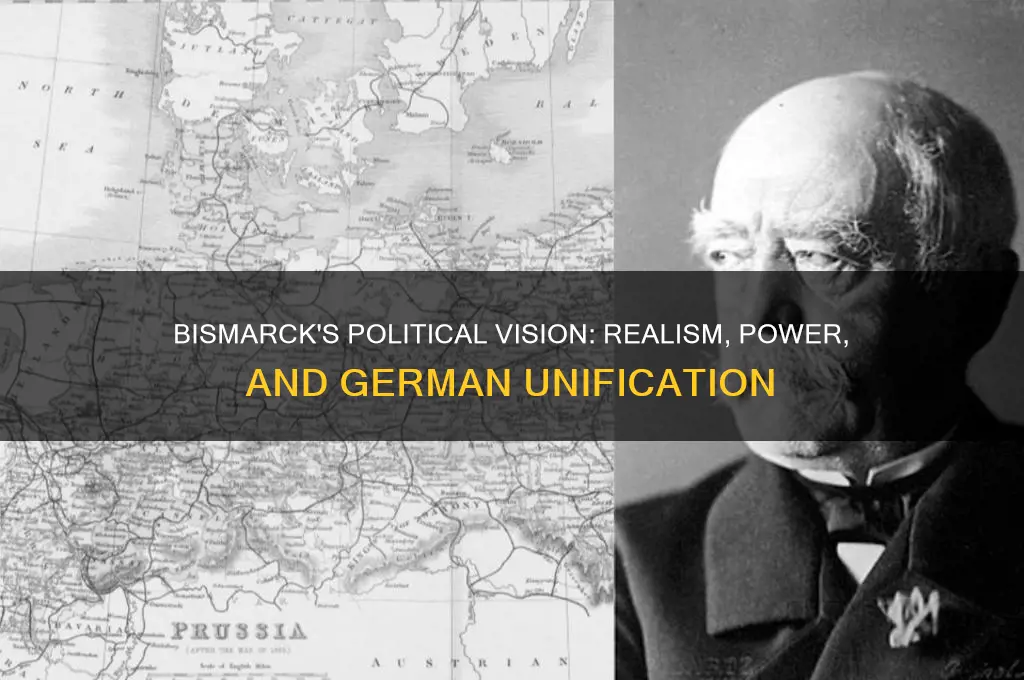

Otto von Bismarck, the dominant political figure in 19th-century Germany, held a pragmatic and conservative political outlook shaped by his commitment to Prussian dominance and the unification of German states under authoritarian leadership. Known as the Iron Chancellor, Bismarck prioritized realpolitik, a pragmatic approach to politics based on practical and material factors rather than ideological notions. He was a staunch nationalist who sought to consolidate German power through a combination of diplomacy, strategic alliances, and, when necessary, military force. Bismarck’s conservatism was rooted in his belief in the preservation of monarchical authority and the suppression of liberal and socialist movements, which he viewed as threats to social order. His policies, such as the creation of the German Empire in 1871 and the implementation of welfare reforms, reflected his dual goals of maintaining stability and securing Germany’s position as a major European power.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Ideology | Pragmatic Realpolitik; conservative nationalism |

| Governance Style | Authoritarian, centralized power under the Kaiser |

| Unification Approach | Blood and Iron (military strength and diplomacy) |

| Foreign Policy | Balance of power, avoidance of long-term alliances |

| Domestic Policy | Anti-Socialist laws, Kulturkampf (struggle against Catholicism) |

| Social Welfare | Introduced early social security programs (sickness, accident insurance) |

| Economic Policy | Protectionist tariffs, support for industrialization |

| Religious Stance | Initially anti-Catholic, later reconciled with the Vatican |

| Constitutional Framework | Semi-parliamentary system with limited democratic elements |

| Colonial Ambition | Limited interest in colonies, focused on European stability |

| Leadership Philosophy | Strong leadership, manipulation of political forces to maintain power |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Realpolitik Focus: Practical, power-based politics over ideology, prioritizing national interest and stability

- Unification Goal: Strategic unification of German states under Prussian leadership

- Balance of Power: Maintaining European equilibrium to secure Germany’s dominance

- Social Reforms: Implementing welfare policies to curb socialism and ensure loyalty

- Anti-Catholicism: Kulturkampf to reduce Catholic Church influence in German politics

Realpolitik Focus: Practical, power-based politics over ideology, prioritizing national interest and stability

Otto von Bismarck's political outlook was deeply rooted in Realpolitik, a pragmatic and power-centric approach to politics that prioritized national interest and stability over abstract ideologies. This philosophy, which translates to "realistic politics," became the cornerstone of his statecraft as the architect of German unification and the first chancellor of the German Empire. Bismarck's Realpolitik focus was characterized by a relentless pursuit of practical solutions to political challenges, often involving calculated diplomacy, strategic alliances, and the use of force when necessary. He believed that politics should be driven by the realities of power dynamics rather than idealistic principles, ensuring that Germany's interests were safeguarded and advanced in a rapidly changing European landscape.

At the core of Bismarck's Realpolitik was the prioritization of national interest above all else. He viewed Germany's unification and its subsequent rise as a great power as paramount, and every political decision he made was filtered through this lens. Bismarck was willing to form alliances with nations whose ideologies clashed with his own if it served Germany's interests. For instance, he forged ties with both conservative monarchies and liberal states, demonstrating a flexibility that was unencumbered by ideological purity. This pragmatic approach allowed him to navigate complex international relations and secure Germany's position as a dominant force in Europe.

Bismarck's focus on stability was another key aspect of his Realpolitik. He understood that internal and external stability were essential for Germany's long-term prosperity and security. Domestically, he implemented policies that balanced the interests of various social groups, such as the working class, through social welfare programs, while also maintaining the power of the aristocracy and the military. This internal equilibrium prevented social unrest and solidified his control. Internationally, Bismarck pursued a policy of equilibrium, often referred to as the "balance of power," to avoid conflicts that could destabilize Europe and threaten Germany's gains. His famous system of alliances, such as the League of Three Emperors and the Dual Alliance with Austria-Hungary, was designed to isolate potential adversaries and maintain peace on Germany's terms.

The practical, power-based nature of Bismarck's politics is perhaps best exemplified by his approach to unification. Rather than relying on popular movements or ideological appeals, he achieved unification through a series of calculated wars—against Denmark, Austria, and France—that demonstrated Prussia's military might and political acumen. These conflicts were not driven by a desire for conquest but by a strategic vision to consolidate German states under Prussian leadership. Bismarck's famous quote, "It is not by speeches and majority votes that the great questions of the day will be decided... but by iron and blood," encapsulates his belief in the primacy of power over rhetoric in achieving political goals.

In summary, Bismarck's Realpolitik focus was a masterclass in practical, power-based politics that prioritized national interest and stability. His ability to set aside ideological differences, manipulate alliances, and use force judiciously allowed him to unify Germany and establish it as a major European power. Bismarck's legacy in this regard remains a defining example of how a pragmatic, results-oriented approach can achieve lasting political success in a complex and competitive international environment. His Realpolitik continues to influence modern political thought, serving as a reminder that in the realm of statecraft, realism often trumps idealism.

Why Does My Polietal Hurt? Causes, Remedies, and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Unification Goal: Strategic unification of German states under Prussian leadership

Otto von Bismarck, the architect of German unification, pursued the strategic unification of German states under Prussian leadership with a combination of realpolitik, diplomatic maneuvering, and calculated use of military force. His political outlook was rooted in the belief that Prussia, with its strong military, efficient bureaucracy, and conservative values, was the natural leader of a unified Germany. Bismarck’s approach was pragmatic, prioritizing power and stability over idealism, and he saw unification as a means to secure Prussia’s dominance in Europe.

Bismarck’s unification goal was driven by the conviction that a fragmented Germany weakened Prussian influence and left the German states vulnerable to external powers, particularly France and Austria. He understood that unification under Prussian leadership would not only enhance Prussia’s power but also create a strong, centralized German state capable of competing with other European great powers. To achieve this, Bismarck strategically exploited existing tensions and rivalries among the German states, positioning Prussia as the indispensable force for unity. He famously declared that the great questions of the time would be decided not by speeches and majority votes but by "blood and iron," emphasizing the role of military strength in achieving his unification goals.

A key aspect of Bismarck’s strategy was the deliberate exclusion of Austria from the unified German state. Known as the "Lesser Germany" solution, this approach ensured Prussian dominance by preventing Austria from rivaling Prussia for leadership. Bismarck achieved this through a series of diplomatic and military actions, most notably the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, which solidified Prussia’s supremacy among the German states. By marginalizing Austria, Bismarck cleared the path for Prussia to lead the unification process without internal competition.

Bismarck also leveraged the Zollverein, the German customs union, as an economic tool to foster unity among the German states. The Zollverein, dominated by Prussia, created economic interdependence and laid the groundwork for political unification. By aligning the economic interests of the German states with Prussian leadership, Bismarck made unification appear both beneficial and inevitable. This economic integration complemented his political and military strategies, creating a multi-faceted approach to achieving his unification goal.

The final phase of Bismarck’s unification strategy culminated in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871. By provoking France into declaring war, Bismarck not only rallied the German states behind Prussia but also demonstrated Prussia’s military prowess and leadership. The war ended with a decisive Prussian victory, and in its aftermath, the German states united under Prussian leadership, with Wilhelm I of Prussia proclaimed as the Emperor of the German Empire in 1871. Bismarck’s strategic vision and relentless pursuit of unification had transformed Prussia into the nucleus of a powerful, unified Germany, achieving his goal of establishing Prussian hegemony in the new nation.

Why Blur Political T-Shirts? Balancing Expression and Legal Boundaries

You may want to see also

Balance of Power: Maintaining European equilibrium to secure Germany’s dominance

Otto von Bismarck, the first chancellor of the German Empire, was a master strategist whose political outlook was deeply rooted in the concept of Realpolitik—practical, power-based politics. Central to his foreign policy was the principle of Balance of Power: Maintaining European equilibrium to secure Germany’s dominance. After unifying Germany in 1871, Bismarck understood that Germany’s position as a new and powerful nation required careful management to avoid provoking its neighbors into hostile alliances. His primary goal was to ensure Germany’s security and preeminence by preventing any single European power or coalition from dominating the continent.

Bismarck’s approach to maintaining the balance of power involved a delicate web of alliances, treaties, and diplomatic maneuvers. He sought to isolate France, Germany’s most immediate rival, by fostering alliances with other European powers. The Three Emperors' League (1873) between Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia was one such initiative, aimed at stabilizing Eastern Europe and preventing conflicts that could threaten Germany. Additionally, the Dual Alliance (1879) between Germany and Austria-Hungary, later expanded to include Italy in the Triple Alliance (1882), further solidified Germany’s central position in Europe. These alliances were designed to deter France from seeking revenge for its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and to ensure that Germany remained at the heart of European diplomacy.

Another key element of Bismarck’s strategy was his ability to play powers against one another, ensuring that no single coalition could form against Germany. For instance, while maintaining ties with Austria-Hungary, he also cultivated a Reinsurance Treaty with Russia in 1887, which neutralized the risk of a two-front war. This treaty allowed Germany to maintain friendly relations with both Eastern powers, preventing them from allying against it. Bismarck’s skill in juggling these relationships demonstrated his commitment to preserving the European equilibrium while safeguarding German interests.

Bismarck also recognized the importance of avoiding unnecessary conflicts that could disrupt the balance of power. He famously stated, “The great questions of the time will not be resolved by speeches and majority decisions... but by iron and blood.” However, he was equally aware that unchecked aggression could lead to isolation. Thus, he pursued a policy of restraint after 1871, focusing on consolidating Germany’s gains rather than seeking further territorial expansion. This approach ensured that Germany remained a dominant but non-threatening power in the eyes of its neighbors.

Ultimately, Bismarck’s focus on maintaining the balance of power was driven by his belief that Germany’s dominance could only be secured in a stable Europe. By preventing any single power from achieving hegemony and by positioning Germany as the linchpin of European diplomacy, he aimed to guarantee his nation’s long-term security and influence. His policies were successful in maintaining peace in Europe during his chancellorship, but the complex alliances he crafted also laid the groundwork for future tensions. Nonetheless, his commitment to the balance of power remains a defining aspect of his political outlook and a testament to his strategic genius.

Medication as a Political Issue: Power, Access, and Healthcare Inequality

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Social Reforms: Implementing welfare policies to curb socialism and ensure loyalty

Otto von Bismarck, the first chancellor of the German Empire, was a pragmatic and conservative statesman who sought to maintain the power of the Prussian aristocracy while ensuring social stability and national unity. His political outlook was deeply influenced by his desire to counter the growing socialist movement, which he saw as a threat to the established order. To achieve this, Bismarck implemented a series of social reforms that combined elements of welfare policy with strategic political calculation. These reforms were designed not only to improve the living conditions of the working class but also to curb the appeal of socialism and secure the loyalty of the masses to the German state and its authoritarian leadership.

Bismarck's approach to social reforms was rooted in his belief that the state had a responsibility to protect its citizens from the harshest effects of industrialization. By introducing welfare policies, he aimed to address the social question—the widespread poverty and discontent among the working class—which had become a fertile ground for socialist ideas. In 1883, Bismarck enacted the Health Insurance Bill, which provided workers with medical care in case of illness. This was followed by the Accident Insurance Act in 1884, ensuring compensation for workers injured on the job, and the Old Age and Disability Insurance Act in 1889, which offered pensions to elderly and disabled workers. These measures were groundbreaking for their time and marked the beginning of the modern welfare state.

The strategic intent behind these reforms was twofold. Firstly, Bismarck sought to undermine the appeal of socialist parties by demonstrating that the state, under his leadership, could address the needs of the working class more effectively than socialist ideologies. By co-opting elements of socialist demands, such as social security, he aimed to neutralize the political threat posed by the Social Democratic Party (SPD). Secondly, these welfare policies were designed to foster a sense of loyalty and dependence on the state among the working class. Bismarck believed that by providing tangible benefits, he could integrate the workers into the national community and align their interests with those of the ruling elite.

Bismarck's welfare policies were not motivated by altruism but by a calculated political strategy. He famously referred to these reforms as "state socialism," emphasizing that they were a means to preserve the existing social hierarchy rather than to transform it. By controlling the implementation of these policies, Bismarck ensured that they did not empower the working class politically but instead reinforced the authority of the state. For instance, the administration of welfare programs was centralized and closely supervised, limiting the influence of trade unions and socialist organizations.

The success of Bismarck's social reforms in curbing socialism was mixed. While they did improve the living conditions of many workers and reduced the immediate appeal of socialist ideas, the SPD continued to grow in strength, particularly after Bismarck's departure from office. However, his policies laid the foundation for the modern welfare state and demonstrated the potential of state intervention in addressing social inequalities. Bismarck's approach remains a significant example of how welfare policies can be used as a tool of political control and social stabilization, reflecting his conservative and pragmatic political outlook.

Can Green Card Holders Participate in Political Party Activities?

You may want to see also

Anti-Catholicism: Kulturkampf to reduce Catholic Church influence in German politics

Otto von Bismarck, the first chancellor of the German Empire, was a pragmatic and authoritarian statesman whose political outlook was shaped by his commitment to Prussian dominance, national unity, and the consolidation of power under the Hohenzollern monarchy. Central to his political strategy was the control of potential threats to the state's authority, including the influence of the Catholic Church. Bismarck’s anti-Catholic policies culminated in the *Kulturkampf* ("culture struggle") during the 1870s, a campaign aimed at reducing the Catholic Church's political and social influence in Germany. This initiative was driven by Bismarck's belief that the Church, particularly its allegiance to the Pope, posed a threat to the newly unified German nation-state.

The *Kulturkampf* was sparked by Bismarck's perception that the Catholic Church, under Pope Pius IX, was interfering in German internal affairs, particularly through the 1870 doctrine of papal infallibility. Bismarck viewed this as a challenge to state authority, as it implied that Catholics owed ultimate loyalty to the Pope rather than to the German Empire. To counter this, Bismarck introduced a series of laws between 1871 and 1875 designed to limit the Church's power. These measures included the *Kanzelparagraph* (Pulpit Law), which prohibited clergy from discussing political issues in their sermons, and laws that restricted the jurisdiction of Catholic bishops and the training of priests. The state also sought to control education by removing Catholic influence from schools and introducing secular curricula.

Bismarck's anti-Catholic policies were not merely religious but deeply political. He aimed to weaken the Catholic Center Party (*Zentrum*), which represented Catholic interests in the Reichstag and was seen as a potential ally of liberal and socialist opponents. By targeting the Church, Bismarck sought to undermine the *Zentrum*'s political base and solidify conservative, Protestant-dominated control over the German state. However, the *Kulturkampf* proved counterproductive, as it galvanized Catholic resistance and strengthened the *Zentrum*'s position, turning it into a more cohesive and determined political force.

The *Kulturkampf* also had international repercussions, straining relations between Germany and the Vatican. The conflict escalated when Bismarck expelled foreign Jesuits and closed Catholic institutions, leading to a diplomatic standoff with Rome. Despite these aggressive measures, the campaign ultimately failed to achieve its goals. By the late 1870s, Bismarck began to reconsider his approach, recognizing that the *Kulturkampf* had alienated a significant portion of the German population and distracted from more pressing issues, such as economic policy and the suppression of socialism.

In 1878, Bismarck shifted his strategy, abandoning the *Kulturkampf* and seeking reconciliation with the Catholic Church. This change was driven by political expediency, as Bismarck needed to secure the support of the *Zentrum* to pass anti-socialist legislation. The rapprochement with the Church marked the end of the *Kulturkampf*, though its legacy persisted in the ongoing tensions between church and state in Germany. Bismarck's anti-Catholic campaign remains a key example of his authoritarian approach to governance and his willingness to use divisive policies to consolidate power, even at the risk of alienating significant segments of the population.

How Political Parties Mobilize Voters: Strategies and Impact Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Bismarck's political outlook was rooted in Realpolitik, prioritizing practical and power-based solutions over idealism. He believed in unifying Germany under Prussian leadership through a combination of diplomacy, strategic alliances, and controlled use of force, as demonstrated in the wars with Denmark, Austria, and France.

Bismarck was a staunch monarchist and saw the monarchy, particularly the Prussian king, as the cornerstone of political stability and national unity. He believed in a strong, centralized authority led by the monarch, with the chancellor playing a key role in governance and foreign policy.

Bismarck was skeptical of liberalism and democracy, viewing them as threats to order and stability. He preferred an authoritarian approach, using conservative and nationalist sentiments to maintain control. While he introduced some social reforms to gain public support, he opposed parliamentary power and prioritized executive authority.