Interest groups and political parties are integral components of modern democratic systems, often intersecting in their efforts to influence policy and shape public opinion. While political parties primarily focus on winning elections and gaining governmental power, interest groups, also known as advocacy groups or lobbies, work to promote specific issues or causes that align with their members' interests. The relationship between these two entities is complex and symbiotic: political parties rely on interest groups for financial support, grassroots mobilization, and expertise on particular issues, while interest groups depend on parties to advance their agendas through legislative action. This dynamic interplay can lead to both collaboration and tension, as parties must balance the demands of various interest groups with broader electoral strategies and public sentiment. Understanding this relationship is crucial for comprehending how power is distributed and exercised within democratic systems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Role in Democracy | Both interest groups and political parties are essential for democratic systems, representing and advocating for citizens' interests. |

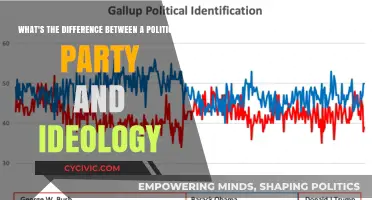

| Representation | Interest groups represent specific interests or causes, while political parties represent broader ideologies and policy agendas. |

| Influence on Policy | Interest groups lobby for specific policies, whereas political parties shape broader legislative agendas and governance. |

| Mobilization of Support | Interest groups mobilize support around specific issues, while political parties mobilize voters for elections and broader political goals. |

| Funding and Resources | Interest groups often provide financial and organizational support to political parties aligned with their goals. |

| Reciprocal Relationship | Political parties may rely on interest groups for grassroots support, while interest groups depend on parties to advance their agendas. |

| Issue Specialization | Interest groups focus on niche issues, whereas political parties address a wide range of societal concerns. |

| Accountability | Political parties are accountable to voters, while interest groups are accountable to their members or stakeholders. |

| Lobbying vs. Governing | Interest groups primarily lobby for change, while political parties are involved in governing and implementing policies. |

| Membership and Structure | Interest groups have voluntary memberships, while political parties have structured memberships and hierarchies. |

| Public Perception | Political parties are often seen as more legitimate in the political process, while interest groups may face scrutiny for narrow focus. |

| Longevity and Goals | Political parties aim for long-term political power, while interest groups focus on achieving specific, often short-term, goals. |

| Coalition Building | Both collaborate to form coalitions, but political parties do so for electoral success, and interest groups for policy influence. |

| Media and Public Outreach | Political parties use media for broad messaging, while interest groups use targeted campaigns to raise awareness on specific issues. |

| Global Influence | Both operate nationally and internationally, but political parties are more integrated into formal governance structures. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Interest groups' influence on party platforms and policies

Interest groups wield significant influence over political party platforms and policies by shaping the priorities and narratives that parties adopt. Through lobbying, campaign contributions, and grassroots mobilization, these groups ensure their specific concerns are reflected in party agendas. For instance, environmental organizations like the Sierra Club have successfully pushed Democratic parties in the U.S. to prioritize climate change legislation, while the National Rifle Association (NRA) has historically influenced Republican stances on gun rights. This dynamic highlights how interest groups act as policy entrepreneurs, injecting their agendas into the broader political discourse.

Consider the mechanics of this influence: interest groups often provide parties with ready-made policy frameworks, research, and messaging strategies. Parties, seeking to appeal to specific voter blocs or secure funding, adopt these frameworks to streamline their platforms. For example, the American Medical Association’s input on healthcare policy has been integral to both Republican and Democratic proposals, though with differing emphases. This symbiotic relationship allows parties to appear responsive to key issues while interest groups gain policy traction. However, this process can also lead to policy polarization, as parties align more closely with the demands of their most vocal or well-funded interest groups.

A cautionary note: while interest group influence can democratize policy-making by amplifying diverse voices, it also risks skewing party platforms toward narrow, special interests. Smaller or less-resourced groups often struggle to compete with corporate or industry giants, creating an imbalance in representation. For instance, labor unions’ influence on Democratic policies has waned compared to corporate lobbying efforts, shifting the party’s focus toward business-friendly initiatives. Parties must balance these pressures to maintain broad-based appeal, but the temptation to cater to powerful interest groups can undermine this goal.

To navigate this landscape, parties should adopt transparency measures, such as disclosing interest group contributions and their policy impacts. Voters, in turn, must critically evaluate party platforms to discern which interests are driving specific policies. For example, tracking the influence of pharmaceutical lobbyists on drug pricing policies can reveal why certain reforms stall. By fostering accountability, both parties and interest groups can contribute to a more equitable policy-making process. Ultimately, the relationship between interest groups and parties is a double-edged sword—one that can either enrich democracy or distort it, depending on how it’s managed.

Youth Disillusionment: Why Young Voters Reject Traditional Political Parties

You may want to see also

Financial ties between interest groups and political parties

Consider the pharmaceutical industry, a prime example of how financial ties operate. In the United States, pharmaceutical companies and their associated interest groups consistently rank among the top donors to both Democratic and Republican parties. These donations often coincide with legislative efforts to protect drug pricing policies or limit government negotiation on drug costs. For instance, during the 2020 election cycle, the pharmaceutical industry contributed over $250 million to federal candidates and political committees. In return, lawmakers have been less likely to support bills that could reduce industry profits, such as Medicare drug price negotiation legislation. This dynamic illustrates how financial ties can skew policy outcomes in favor of well-funded interest groups.

To understand the mechanics of these ties, it’s instructive to examine the role of Political Action Committees (PACs) and Super PACs. PACs allow interest groups to pool resources and donate directly to candidates, while Super PACs can raise and spend unlimited funds independently to support or oppose candidates. For example, the National Rifle Association (NRA) uses its PAC to funnel millions into campaigns of pro-gun candidates, ensuring their agenda remains a priority. However, this system is not without risks. Critics argue that such financial mechanisms create a pay-to-play environment, where access to policymakers is disproportionately granted to those with deep pockets, undermining democratic equality.

A comparative analysis reveals that financial ties vary significantly across political systems. In countries with stricter campaign finance regulations, such as Canada or Germany, the influence of interest groups is more regulated, reducing the potential for undue sway. In contrast, the U.S. system, with its Citizens United ruling allowing corporate spending in elections, exemplifies a more open financial relationship between interest groups and parties. This comparison underscores the importance of regulatory frameworks in shaping the nature and extent of these ties.

In practical terms, understanding these financial ties is crucial for voters and policymakers alike. Voters can scrutinize campaign finance disclosures to identify which interest groups are backing their candidates, enabling more informed decisions. Policymakers, on the other hand, can advocate for reforms such as public financing of elections or stricter disclosure requirements to mitigate the influence of money in politics. While financial ties between interest groups and political parties are unlikely to disappear, transparency and accountability can help ensure they do not distort the democratic process.

Exploring the Political Affiliation of WRI: Unveiling Its Party Ties

You may want to see also

Role of interest groups in candidate endorsements

Interest groups play a pivotal role in shaping political landscapes, particularly through their strategic endorsements of candidates. These endorsements are not merely symbolic gestures; they are calculated moves designed to influence election outcomes and advance specific agendas. By aligning with candidates who share their values or policy priorities, interest groups can amplify their voice in the political arena. For instance, the National Rifle Association (NRA) has historically endorsed candidates who support Second Amendment rights, leveraging its vast membership and financial resources to sway public opinion and electoral results.

The process of endorsing candidates involves a meticulous evaluation of a candidate’s track record, policy positions, and electability. Interest groups often conduct thorough research, including interviews, surveys, and analysis of voting histories, to determine the best fit. This strategic approach ensures that their endorsement carries weight and maximizes their impact. For example, environmental organizations like the Sierra Club use a scoring system to assess candidates’ environmental policies, endorsing only those who meet their stringent criteria. This method not only strengthens the credibility of the endorsement but also signals to voters which candidates are genuinely committed to the group’s cause.

Endorsements from interest groups can significantly alter the trajectory of a campaign. They provide candidates with access to the group’s network, fundraising capabilities, and grassroots support, which can be crucial in tight races. In the 2020 U.S. Senate elections, endorsements from labor unions like the AFL-CIO were instrumental in mobilizing working-class voters in key battleground states. Conversely, a lack of endorsement from a powerful interest group can signal weakness or misalignment, potentially deterring donors and supporters. This dynamic underscores the dual role of endorsements as both a tool for candidate empowerment and a mechanism for holding politicians accountable to specific constituencies.

However, the influence of interest groups in candidate endorsements is not without controversy. Critics argue that such endorsements can distort the democratic process by prioritizing narrow interests over the broader public good. For instance, pharmaceutical industry groups endorsing candidates who oppose drug pricing reforms can perpetuate policies that harm consumers. To mitigate these risks, some interest groups have adopted transparency measures, such as publicly disclosing their endorsement criteria and funding sources. Voters, too, must remain vigilant, critically evaluating endorsements in the context of their own priorities rather than accepting them at face value.

In conclusion, the role of interest groups in candidate endorsements is a double-edged sword—a powerful tool for advancing specific agendas but one that requires careful scrutiny. By understanding the mechanics and implications of these endorsements, voters and policymakers can navigate their influence more effectively. Interest groups, for their part, must balance their advocacy with a commitment to transparency and accountability to maintain their legitimacy in the political ecosystem.

How Political Parties Select Their Presidential Candidates: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Party alignment with interest group ideologies and goals

Political parties often align with interest groups to solidify their ideological stance and broaden their electoral appeal. For instance, the Democratic Party in the United States frequently partners with environmental interest groups like the Sierra Club, whose goals align with the party’s emphasis on climate action and sustainability. This alignment not only reinforces the party’s commitment to green policies but also mobilizes a dedicated voter base passionate about environmental issues. Conversely, the Republican Party aligns with interest groups like the National Rifle Association (NRA), reflecting shared values around gun rights and individual freedoms. These strategic alliances demonstrate how parties use interest groups to sharpen their identity and attract specific demographics.

Alignment with interest groups is not without risks. Parties must balance the demands of these groups with broader public opinion to avoid alienating moderate voters. For example, a party’s close association with a single-issue interest group, such as an anti-abortion organization, may energize its base but repel independent voters who prioritize other issues. Parties must carefully calibrate their relationships, ensuring that alignment with interest group ideologies does not overshadow their ability to address diverse constituent concerns. This delicate balance requires constant negotiation and strategic communication.

To maximize the benefits of such alignments, parties should adopt a multi-step approach. First, identify interest groups whose goals overlap significantly with the party’s core platform. Second, establish formal partnerships through joint campaigns, policy endorsements, or funding agreements. Third, leverage these alliances to amplify messaging and mobilize supporters during elections. For instance, the Labor Party in Australia effectively aligns with trade unions, using their organizational strength to campaign for workers’ rights and secure votes. This structured approach ensures that alignment with interest groups translates into tangible political gains.

A cautionary note: parties must avoid becoming captive to interest group agendas. Over-reliance on these groups can lead to policy rigidity and a loss of flexibility in responding to shifting public priorities. For example, the Conservative Party in the UK faced criticism for its alignment with financial sector interest groups, which some argued prioritized corporate interests over those of ordinary citizens. Parties should maintain autonomy by diversifying their alliances and regularly reassessing the relevance of interest group partnerships to their long-term goals.

In conclusion, party alignment with interest group ideologies and goals is a powerful tool for strengthening political identity and mobilizing support. However, it requires strategic planning, careful balancing, and periodic evaluation to ensure that such alignments serve the party’s broader objectives without compromising its appeal to a wider electorate. By mastering this dynamic, parties can harness the energy and resources of interest groups while maintaining their ability to adapt and lead.

Military in Politics: Causes, Consequences, and Global Implications

You may want to see also

Interest groups' mobilization of voters for political parties

Interest groups often serve as the grassroots engine for political parties, mobilizing voters through targeted campaigns and community engagement. Consider the National Rifle Association (NRA) in the United States, which consistently activates its members to support candidates aligned with gun rights. By leveraging its extensive network, the NRA not only endorses politicians but also organizes rallies, distributes voter guides, and employs door-to-door canvassing. This strategic mobilization ensures that its base turns out in force, often swaying elections in key districts. Such efforts highlight how interest groups can act as force multipliers for political parties, turning abstract policy goals into tangible electoral outcomes.

To effectively mobilize voters, interest groups must first identify their core demographic and craft messages that resonate. For instance, environmental organizations like the Sierra Club focus on young voters and urban populations, using social media and local events to promote pro-climate candidates. A practical tip for groups aiming to replicate this success is to segment their audience based on age, location, and issue priorities. For voters aged 18–30, digital campaigns with concise, visually engaging content yield higher engagement. Meanwhile, older demographics may respond better to traditional methods like mailers or town hall meetings. Tailoring the approach ensures that mobilization efforts are not just broad but also deeply impactful.

A cautionary note: over-reliance on interest groups for voter mobilization can backfire if their messaging alienates moderate voters. Take the case of single-issue groups like pro-life organizations, which sometimes struggle to appeal to independents when their campaigns appear too extreme. Political parties must balance the enthusiasm interest groups bring with the need for broader appeal. One strategy is to encourage interest groups to frame their advocacy within a larger, more inclusive narrative. For example, instead of focusing solely on gun rights, the NRA might emphasize broader themes of personal freedom and constitutional rights, thereby attracting a wider audience.

Comparatively, interest groups in multiparty systems, such as those in Europe, often play a more nuanced role in voter mobilization. In Germany, labor unions like the German Trade Union Confederation (DGB) mobilize workers not just for one party but for a spectrum of left-leaning parties, depending on regional preferences. This approach contrasts with the U.S., where interest groups typically align with one major party. The takeaway here is that flexibility in mobilization strategies can maximize influence, especially in fragmented political landscapes. Parties and interest groups alike should study these cross-national examples to refine their voter engagement tactics.

Ultimately, the mobilization of voters by interest groups is a high-stakes endeavor requiring precision, adaptability, and strategic alignment. Whether through digital campaigns, community events, or targeted messaging, these groups can significantly amplify a party’s reach. However, success hinges on understanding the audience, balancing extremism with inclusivity, and learning from diverse political contexts. For political parties, fostering strong relationships with interest groups while maintaining autonomy is key. For interest groups, the challenge lies in translating passion into votes without losing sight of the broader electorate. Done right, this partnership can be a decisive factor in electoral victories.

Building a Radical Political Party: Strategies for Grassroots Revolution

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Interest groups and political parties often work together to achieve shared goals. Interest groups advocate for specific policies or issues, while political parties aim to win elections and implement broader agendas. Interest groups provide parties with expertise, funding, and grassroots support, while parties offer a platform to advance interest group priorities.

Interest groups influence political parties through lobbying, campaign contributions, and mobilizing voters. They shape party platforms by pushing for specific policies and can sway party positions on key issues. Additionally, interest groups often endorse candidates aligned with their goals, bolstering their electoral chances.

No, political parties and interest groups do not always align. While they may share common objectives, interest groups often focus on narrow issues, whereas parties must appeal to a broader electorate. This can lead to tensions when party priorities conflict with interest group demands.

Interest groups focus on advocating for specific issues or policies, often representing a particular segment of society. They do not run candidates for office. In contrast, political parties seek to win elections, control government, and implement a broader set of policies. Parties are more comprehensive in their goals and organizational structure.