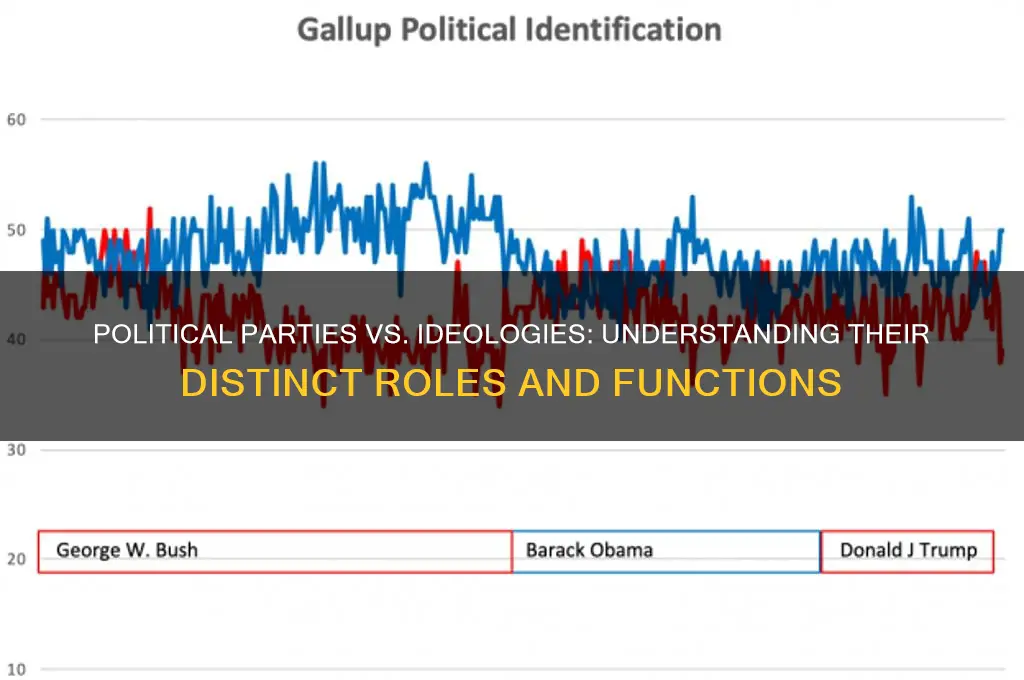

Understanding the distinction between a political party and an ideology is crucial for grasping the dynamics of political systems. A political party is an organized group of people who share common goals and seek to influence or control government power through elections and policy-making. Parties are practical entities focused on winning elections, mobilizing supporters, and implementing specific policies. In contrast, an ideology is a set of beliefs, values, and principles that guide political thought and action, often providing a broader framework for understanding society and governance. While a party may be guided by an ideology, it is not synonymous with it; parties can evolve, compromise, or shift their positions to adapt to political realities, whereas ideologies tend to be more rigid and enduring. For example, socialism is an ideology, while the Democratic or Labour parties in various countries are organizations that may adopt socialist principles but also incorporate other ideas to appeal to a wider electorate. Thus, ideologies shape parties, but parties are the vehicles through which ideologies are translated into political practice.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition Focus: Parties organize people; ideologies provide beliefs and principles guiding political actions

- Structure vs. Ideas: Parties have hierarchies; ideologies are abstract frameworks for thought

- Flexibility: Parties adapt policies; ideologies remain rigid, rooted in core values

- Purpose: Parties seek power; ideologies aim to shape societal norms and systems

- Membership: Parties require active members; ideologies can influence passive supporters

Definition Focus: Parties organize people; ideologies provide beliefs and principles guiding political actions

Political parties and ideologies are often conflated, yet their roles are distinct and complementary. Parties serve as the machinery that mobilizes individuals into collective action, while ideologies furnish the intellectual framework that directs this action. Consider the Democratic Party in the United States, which organizes millions of voters, fundraisers, and volunteers. Its effectiveness hinges on structure—local chapters, national committees, and leadership hierarchies. In contrast, the ideology of liberalism, often associated with the party, provides the principles of individual freedom, equality, and social justice that guide its policy decisions. Without the party, the ideology remains abstract; without the ideology, the party lacks direction.

To illustrate this dynamic, examine the Labour Party in the United Kingdom. Its organizational apparatus—trade union affiliations, constituency labor parties, and annual conferences—ensures broad participation and resource mobilization. Simultaneously, its socialist ideology informs policies on wealth redistribution, public services, and workers’ rights. The party’s structure turns these principles into actionable campaigns, legislation, and governance. This interplay is critical: a party without ideological grounding risks becoming a hollow shell, while an ideology without organizational backing remains a theoretical construct.

A persuasive argument for this distinction lies in the historical rise of fascism. Fascist ideologies, rooted in nationalism and authoritarianism, gained traction not through their inherent appeal but via parties like Mussolini’s National Fascist Party or Hitler’s Nazi Party. These organizations employed rallies, propaganda, and hierarchical systems to mobilize masses. The ideology provided the narrative, but the parties transformed it into a movement. This example underscores the danger of conflating the two: ideologies can be toxic, but it is the organizational power of parties that enables their implementation.

Practically, understanding this difference is essential for political engagement. If you aim to influence policy, joining a party offers a structured pathway to participate in elections, lobbying, and grassroots campaigns. However, if your goal is to shape the underlying values of society, engaging with ideological discourse—through think tanks, publications, or academic research—is more effective. For instance, environmental activists might join the Green Party to organize protests and run candidates, while simultaneously contributing to the ideology of ecological sustainability through research and advocacy.

In conclusion, parties and ideologies are interdependent yet distinct. Parties are the vehicles for political action, while ideologies are the compasses that guide it. Recognizing this difference allows for more strategic and effective political participation. Whether you’re organizing a local campaign or debating policy principles, clarity on this distinction ensures your efforts are both structured and purposeful.

Exploring Alao Ajala's Political Affiliation: Which Party Does He Belong To?

You may want to see also

Structure vs. Ideas: Parties have hierarchies; ideologies are abstract frameworks for thought

Political parties and ideologies, though often conflated, serve distinct roles in the political landscape. At their core, parties are organizational structures designed to achieve and maintain power, while ideologies are abstract frameworks that guide thought and action. This distinction is crucial for understanding how political systems function and evolve. Parties rely on hierarchies to coordinate efforts, mobilize resources, and make decisions, whereas ideologies transcend such structures, offering principles and values that can be interpreted and applied in myriad ways.

Consider the Democratic Party in the United States. Its structure includes local chapters, state committees, and a national leadership, all working within a defined hierarchy to nominate candidates, craft policies, and win elections. In contrast, liberalism—an ideology often associated with the Democratic Party—is a broader set of ideas about individual rights, free markets, and limited government. While the party’s hierarchy ensures operational efficiency, liberalism as an ideology exists independently, influencing not only Democrats but also other groups and individuals worldwide. This example illustrates how parties are bound by their organizational needs, while ideologies operate as flexible, abstract concepts.

To further clarify, imagine building a house. The political party is the construction crew—organized, hierarchical, and task-oriented—focused on assembling materials and meeting deadlines. The ideology, however, is the architectural blueprint—an abstract design that guides the overall vision but leaves room for interpretation and adaptation. Just as multiple crews can use the same blueprint to build different houses, multiple parties can adopt the same ideology yet implement it in distinct ways. This analogy underscores the functional difference between the structured, goal-oriented nature of parties and the abstract, guiding role of ideologies.

Practical implications arise from this distinction. For instance, a party’s hierarchy can stifle innovation if decision-making becomes too centralized, while an ideology’s abstract nature can lead to fragmentation if interpretations diverge too widely. To balance these dynamics, parties often adopt internal mechanisms like caucuses or platforms to align their structure with ideological principles. Conversely, ideologues may form think tanks or advocacy groups to promote their ideas without the constraints of a hierarchical organization. Understanding this interplay is essential for anyone seeking to navigate or influence political systems effectively.

In conclusion, the tension between structure and ideas defines the relationship between political parties and ideologies. Parties thrive on hierarchies that enable action, while ideologies flourish as abstract frameworks that inspire thought. Recognizing this difference allows for a more nuanced appreciation of how political systems operate and how change occurs. Whether you’re a voter, activist, or policymaker, grasping this dynamic equips you to engage more thoughtfully with the complex interplay of organization and ideology in politics.

Why Politics Matters: Exploring Gerry Stoker's Insights on Civic Engagement

You may want to see also

Flexibility: Parties adapt policies; ideologies remain rigid, rooted in core values

Political parties and ideologies often blur in public discourse, yet their relationship to flexibility reveals a stark contrast. Parties, as organizational entities, thrive on adaptability, adjusting policies to capture shifting voter sentiments or respond to crises. For instance, the Democratic Party in the United States has evolved from a pro-segregation stance in the mid-20th century to championing civil rights and social justice today. This malleability is a survival mechanism, ensuring relevance in a dynamic political landscape. Ideologies, however, operate differently. Rooted in core principles—like socialism’s emphasis on collective ownership or libertarianism’s prioritization of individual freedom—they resist change, serving as moral and philosophical anchors. This rigidity can make ideologies timeless but also limits their practical application in a changing world.

Consider the steps involved in policy adaptation within a party versus the constraints of ideological purity. A party might conduct polls, analyze demographic trends, or convene focus groups to gauge public opinion before revising a stance on healthcare or taxation. This process is iterative, often driven by electoral strategy rather than principle. In contrast, an ideology demands adherence to its foundational tenets, even if they clash with contemporary realities. For example, a Marxist-Leninist party might struggle to reconcile its anti-capitalist dogma with the need to attract foreign investment in a developing economy. The takeaway here is clear: parties bend to fit the times, while ideologies demand the times bend to them.

This distinction has practical implications for governance and activism. Parties that embrace flexibility can enact incremental change, as seen in the gradual expansion of welfare programs in Nordic social democracies. However, this adaptability risks diluting core values, leading to accusations of opportunism. Ideologies, by contrast, inspire movements and revolutions, as exemplified by the role of feminist theory in driving global gender equality campaigns. Yet their inflexibility can alienate pragmatists and hinder progress in pluralistic societies. For instance, purist environmental ideologies often reject technological solutions like nuclear energy, despite its potential to reduce carbon emissions.

To navigate this tension, individuals and organizations must strike a balance. Parties can adopt a "core-periphery" approach, preserving non-negotiable principles while allowing peripheral policies to evolve. For example, a conservative party might maintain its commitment to fiscal responsibility while updating its stance on LGBTQ+ rights. Similarly, ideological movements can incorporate contextual analysis, as seen in Islamic modernism’s reinterpretation of religious texts to align with democratic values. The key is to recognize that flexibility is not a betrayal of values but a tool for their realization.

Ultimately, the interplay between party adaptability and ideological rigidity shapes political outcomes. Parties that rigidly adhere to outdated policies risk obsolescence, as seen in the decline of communist parties in Eastern Europe post-1989. Conversely, ideologies that refuse to engage with practical realities remain confined to the realm of theory. By understanding this dynamic, voters, activists, and policymakers can better navigate the complexities of political engagement, ensuring that both flexibility and conviction play their rightful roles in shaping society.

Major Parties' Influence: Shaping Policies and Power in American Politics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Purpose: Parties seek power; ideologies aim to shape societal norms and systems

Political parties and ideologies, though often intertwined, serve fundamentally different purposes. Parties are vehicles for gaining and wielding political power, operating within the existing structures of governance. Their primary goal is to win elections, secure seats, and implement policies that align with their platform. This pragmatic focus means parties are inherently flexible, adapting their strategies and even their stances to appeal to voters and outmaneuver opponents. For instance, a party might shift its position on taxation or healthcare to capture the middle ground in an election, prioritizing electoral success over ideological purity.

Ideologies, in contrast, are frameworks of ideas and values that seek to shape the very fabric of society. They are not bound by the immediate demands of elections or the constraints of governance. Instead, ideologies aim to influence how people think, behave, and organize themselves. Consider socialism, which advocates for collective ownership of resources and equitable distribution of wealth. Its purpose is not to win elections but to challenge capitalist norms and redefine societal priorities. Ideologies operate on a longer time horizon, often inspiring movements and cultural shifts that transcend individual political cycles.

This distinction becomes clearer when examining historical examples. The Democratic Party in the United States, for instance, has evolved from a pro-slavery, agrarian-focused entity in the 19th century to a modern coalition advocating for social justice and progressive policies. Its purpose has always been to gain power, adapting its platform to reflect changing voter demographics and political landscapes. Meanwhile, feminism as an ideology has consistently aimed to reshape societal norms around gender roles, equality, and rights, regardless of which party holds power. Its impact is measured in cultural and systemic changes, not electoral victories.

Practical implications arise from this difference in purpose. For parties, success is quantifiable: votes cast, seats won, policies enacted. Strategies focus on messaging, coalition-building, and resource allocation. For ideologies, success is more abstract: shifts in public opinion, changes in institutional practices, and the embedding of new values in society. Advocates of ideologies must engage in education, activism, and cultural production to achieve their goals. For example, environmentalism as an ideology has driven global conversations about sustainability, influencing everything from consumer behavior to international treaties, while green parties worldwide work within political systems to translate these ideas into policy.

In essence, parties are tools for governing, while ideologies are blueprints for societal transformation. Understanding this distinction is crucial for anyone navigating the political landscape. Parties may adopt ideological principles, but their ultimate aim is power. Ideologies, however, transcend the political arena, seeking to redefine the rules of the game itself. This dynamic interplay between power and principles shapes the trajectory of societies, highlighting the complementary yet distinct roles of parties and ideologies in political life.

Dylan Ratigan's Political Party: Unraveling His Ideological Affiliations

You may want to see also

Membership: Parties require active members; ideologies can influence passive supporters

Political parties thrive on the energy and commitment of their members. These individuals are the lifeblood of the organization, actively participating in meetings, fundraising, campaigning, and even running for office. Think of them as the foot soldiers in the battle for political power. Without dedicated members, a party struggles to exist, let alone achieve its goals. Consider the Democratic and Republican parties in the United States. Their strength lies not just in their elected officials but in the millions of registered members who knock on doors, make phone calls, and donate money.

Membership requirements vary. Some parties have strict criteria, demanding ideological purity and significant time commitments. Others are more open, welcoming anyone who shares broad principles. Regardless, active participation is key. Members are expected to contribute their time, resources, and enthusiasm to advance the party's agenda.

Ideologies, on the other hand, operate on a different plane. They are sets of beliefs and values that can inspire and guide individuals, even if those individuals never formally join a political party. Think of socialism, conservatism, or environmentalism. These ideologies can resonate deeply with people, shaping their worldview and influencing their voting behavior, even if they never attend a rally or donate to a campaign. A person might strongly believe in social justice and vote consistently for candidates who champion those ideals, without ever becoming a card-carrying member of a socialist party.

Ideologies spread through various channels: books, media, education, and personal interactions. They can inspire passive supporters who, while not actively engaged in party politics, still contribute to the broader political landscape by advocating for their beliefs in their daily lives and through their choices as consumers and citizens.

This distinction highlights a crucial difference in how parties and ideologies function. Parties rely on a core group of dedicated members to drive their machinery, while ideologies can exert influence through a much wider, often less organized, network of sympathizers. Understanding this dynamic is essential for comprehending the complex relationship between political organizations and the ideas that fuel them.

Melissa Nelson's Political Party Affiliation: Uncovering Her Political Leanings

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political party is an organized group that seeks to gain and exercise political power, while an ideology is a set of beliefs, values, and principles that guide political thought and action.

While rare, a political party can exist without a clear ideology, but it typically aligns with or adopts one to provide a framework for its policies and goals.

An ideology shapes a party’s platform, policies, and decisions by providing a foundational set of beliefs that guide its actions and appeals to its supporters.

Yes, multiple parties can share the same or similar ideologies but may differ in their strategies, priorities, or interpretations of those ideologies.

Yes, individuals may join a party for practical reasons, such as career advancement or shared policy goals, even if they do not fully subscribe to its underlying ideology.