Interest groups and political parties are both integral components of democratic systems, yet they serve distinct purposes and operate in different ways. Interest groups, also known as advocacy groups or lobbies, are organizations formed around specific issues, causes, or shared interests, such as environmental protection, labor rights, or business regulations. Their primary goal is to influence public policy and decision-making by advocating for their members' concerns, often through lobbying, public campaigns, or legal action. In contrast, political parties are broader coalitions of individuals with shared ideological, economic, or social goals, aiming to gain political power by winning elections and controlling government institutions. While interest groups focus on specific issues and may work across party lines, political parties seek to implement comprehensive agendas and represent a wider spectrum of policies, typically competing for electoral support and governance. Understanding the differences between these two entities is crucial for grasping the dynamics of political participation and representation in democratic societies.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Membership Focus: Interest groups advocate specific issues; parties seek political power through elections

- Goals: Interest groups push policies; parties aim to win and govern

- Structure: Interest groups are issue-based; parties have hierarchical, national organizations

- Participation: Interest groups allow non-partisan involvement; parties require partisan commitment

- Funding Sources: Interest groups rely on donations; parties depend on broad fundraising networks

Membership Focus: Interest groups advocate specific issues; parties seek political power through elections

Interest groups and political parties differ fundamentally in their membership focus, which shapes their goals, strategies, and impact on the political landscape. Interest groups are united by a shared concern for specific issues, such as environmental conservation, gun rights, or healthcare reform. Their membership is often driven by passion for these causes, and their advocacy efforts are laser-focused on influencing policy outcomes related to their niche. For example, the Sierra Club mobilizes its members to lobby for climate legislation, while the National Rifle Association (NRA) campaigns against gun control measures. This issue-specific focus allows interest groups to attract members who are deeply invested in their cause, fostering a highly engaged and motivated base.

Political parties, in contrast, operate on a broader spectrum, seeking to aggregate diverse interests under a unified platform to win elections and secure political power. Their membership is not defined by a single issue but by a shared ideological or policy orientation. For instance, the Democratic Party in the United States encompasses environmentalists, labor unions, and social justice advocates, while the Republican Party includes fiscal conservatives, social conservatives, and business interests. This broad-based approach enables parties to appeal to a wider electorate, but it also requires them to balance competing priorities and make compromises to maintain coalition cohesion.

The distinct membership focus of interest groups and political parties leads to different engagement strategies. Interest groups often employ grassroots tactics, such as petition drives, public demonstrations, and targeted lobbying, to pressure policymakers on their specific issues. They may also use litigation or media campaigns to amplify their message. Political parties, however, focus on electoral strategies, such as candidate recruitment, fundraising, and voter mobilization, to secure control of government institutions. While interest groups aim to influence the agenda from the outside, parties seek to shape policy from within the political system by winning elections and appointing officials who align with their platform.

A practical takeaway for individuals navigating the political landscape is to recognize the complementary roles of interest groups and political parties. Joining an interest group allows one to advocate for a specific cause with like-minded individuals, while affiliating with a political party provides an opportunity to influence broader governance and policy direction. For example, a voter concerned about climate change might join the Sierra Club to push for environmental regulations while also supporting a political party that prioritizes green energy policies. Understanding these differences can help individuals maximize their impact by engaging with both types of organizations strategically.

In conclusion, the membership focus of interest groups and political parties reflects their distinct purposes: interest groups rally around specific issues, fostering deep engagement on targeted causes, while political parties seek to aggregate diverse interests to win elections and wield political power. This divergence shapes their strategies, membership bases, and contributions to the democratic process. By recognizing these differences, individuals can more effectively participate in advocacy and electoral politics, aligning their efforts with organizations that match their goals and values.

Discover Your UK Political Party: A Comprehensive Guide to Alignment

You may want to see also

Goals: Interest groups push policies; parties aim to win and govern

Interest groups and political parties, though often intertwined in the political landscape, operate with fundamentally different goals. Interest groups are laser-focused on influencing policy outcomes that directly benefit their specific constituency, whether it’s environmental regulations, gun rights, or healthcare reform. Their success is measured by the passage of legislation or the defeat of bills that align with their interests. For instance, the National Rifle Association (NRA) doesn’t aim to win elections; it aims to ensure that gun control measures are blocked or weakened. This narrow, policy-driven focus allows interest groups to mobilize resources and expertise in ways that parties, with their broader agendas, cannot.

Political parties, in contrast, are in the business of winning elections and securing power. Their primary goal is to elect candidates who will implement a broader platform of policies, not just one or two specific issues. Parties must appeal to a diverse coalition of voters, which often requires balancing competing interests and making compromises. For example, the Democratic Party in the U States advocates for a range of issues, from climate change to economic equality, but its ultimate success is measured by its ability to win elections and control government institutions. This broader focus necessitates a different strategy—one that prioritizes coalition-building and electoral tactics over single-issue advocacy.

Consider the practical implications of these differing goals. Interest groups often employ lobbying, grassroots mobilization, and litigation to achieve their policy objectives. They may target specific lawmakers, draft legislation, or launch public awareness campaigns. Political parties, however, invest heavily in campaign infrastructure, candidate recruitment, and voter turnout efforts. While interest groups might celebrate a policy victory without ever winning an election, parties must translate their policy goals into electoral success to have any impact. This distinction highlights why interest groups can sometimes be more effective at shaping specific policies, while parties are better equipped to govern comprehensively.

A key takeaway is that interest groups and political parties are complementary yet distinct actors in the political system. Interest groups provide the specialized pressure needed to push policies forward, while parties provide the framework for implementing those policies through governance. For individuals looking to engage in politics, understanding this difference is crucial. If you’re passionate about a single issue, joining an interest group might be more effective. If your goal is to shape a broader vision for society, working within a political party could be the better path. Both are essential, but their roles—and their measures of success—are fundamentally different.

Elena Kagan's Political Party: Unraveling Her Ideological Affiliation and Stance

You may want to see also

Structure: Interest groups are issue-based; parties have hierarchical, national organizations

Interest groups and political parties differ fundamentally in their organizational structures, which directly reflects their distinct purposes and goals. Interest groups are typically issue-based, meaning they form around a specific cause, policy, or concern. For example, the Sierra Club focuses on environmental conservation, while the National Rifle Association (NRA) advocates for gun rights. Their structure is often decentralized, with local chapters or affiliates working independently but aligned under a common mission. This flexibility allows them to mobilize quickly and target specific issues without the constraints of a broader political agenda.

In contrast, political parties operate within a hierarchical, national framework designed to win elections and wield political power. The Democratic and Republican parties in the United States exemplify this model, with layers of leadership from local committees to national headquarters. This structure ensures consistency in messaging, fundraising, and candidate support across regions. While parties may address a wide range of issues, their primary focus is on maintaining and expanding their electoral influence, often requiring compromises to appeal to diverse voter bases.

The issue-based nature of interest groups fosters a laser-like focus, enabling them to delve deeply into their chosen cause. For instance, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) meticulously tracks legislation affecting civil liberties and mounts legal challenges when necessary. This specialization makes them invaluable resources for policymakers and the public alike. However, their narrow focus can limit their influence on broader political landscapes, as they are not positioned to shape comprehensive governance strategies.

Political parties, with their hierarchical organizations, are better equipped to manage the complexities of governing. Their national reach allows them to coordinate campaigns, draft platforms, and negotiate across states and districts. Yet, this structure can also lead to internal power struggles and ideological divides, as seen in recent years within both major U.S. parties. Balancing unity with diversity of thought remains a perennial challenge for these organizations.

In practice, understanding these structural differences is crucial for effective advocacy and political engagement. Interest groups thrive by staying agile and focused, while political parties succeed by maintaining discipline and scale. For individuals or organizations seeking to influence policy, aligning with an interest group may offer a direct pathway to impact on a specific issue, whereas joining a political party provides a platform to shape broader governance. Recognizing these distinctions ensures strategic engagement in the political process.

Warren G. Harding's Political Party: Uncovering His Republican Roots

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Participation: Interest groups allow non-partisan involvement; parties require partisan commitment

Interest groups and political parties differ fundamentally in their participation requirements, offering distinct pathways for civic engagement. Interest groups, by design, foster non-partisan involvement, welcoming individuals who share specific concerns or goals without demanding allegiance to a broader political ideology. For instance, environmental advocacy groups like the Sierra Club attract members solely based on their commitment to conservation, regardless of whether they identify as liberal, conservative, or independent. This inclusivity allows for a diverse coalition, amplifying the group’s influence by uniting people across the political spectrum behind a common cause.

In contrast, political parties require partisan commitment, anchoring participation in adherence to a predefined set of values and policies. Joining a party often means aligning with its platform, even if one disagrees with certain aspects. For example, a Democrat must generally support the party’s stance on issues like healthcare and taxation, while a Republican must align with its views on fiscal responsibility and social conservatism. This ideological cohesion is essential for parties to function as cohesive units in the political system, but it can alienate those who hold nuanced or cross-cutting views.

The practical implications of these participation models are significant. Interest groups provide a low-barrier entry point for civic engagement, ideal for individuals aged 18–25 who are still forming their political identities or for older adults seeking issue-specific action without partisan baggage. For instance, a college student passionate about gun control can join Everytown for Gun Safety without needing to commit to a party. Conversely, political parties demand a higher level of ideological consistency, making them better suited for those with well-defined political beliefs. A 40-year-old with a history of voting Republican may find greater fulfillment in party activism, even if it means occasionally compromising on specific issues.

To maximize participation, individuals should assess their priorities. If flexibility and issue-specific action are key, interest groups offer a practical starting point. For example, someone concerned about climate change can join the Sunrise Movement and participate in local campaigns without partisan constraints. However, if influencing broader governance and policy-making is the goal, joining a political party may be more effective, despite the ideological commitment required. A tip for newcomers: start by attending local interest group meetings or party caucuses to gauge the level of partisan expectation before fully committing.

Ultimately, the choice between interest groups and political parties hinges on one’s tolerance for ideological alignment versus issue-specific focus. Interest groups democratize participation by removing partisan barriers, while political parties consolidate power through ideological unity. By understanding these dynamics, individuals can strategically engage in ways that align with their values and goals, whether they seek to drive narrow policy changes or shape the broader political landscape.

Do Political Parties Strengthen Governments or Sow Division?

You may want to see also

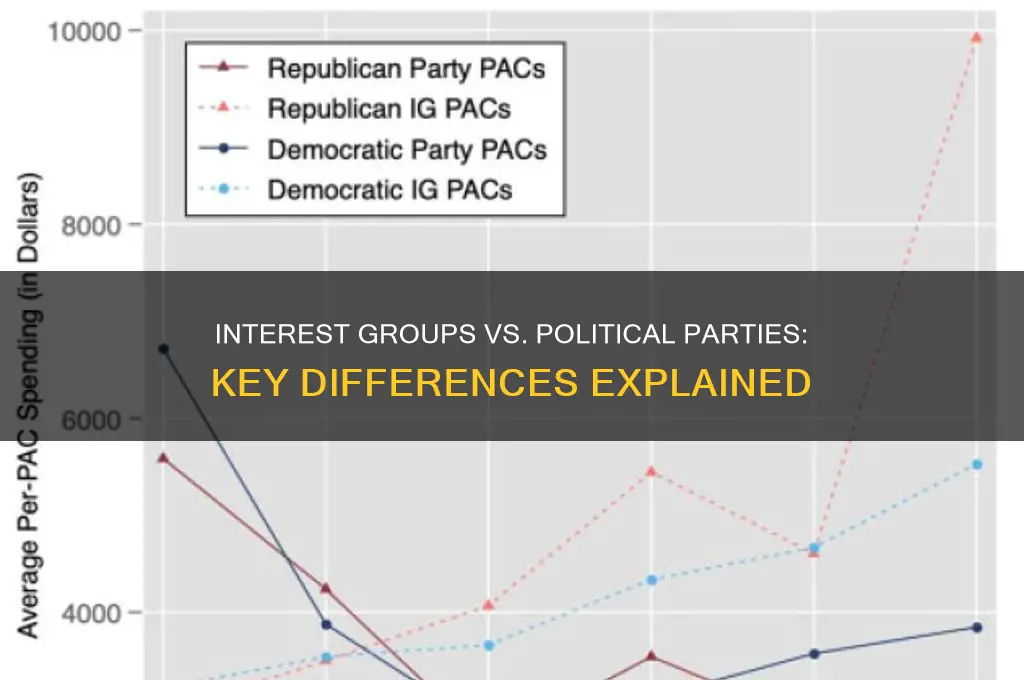

Funding Sources: Interest groups rely on donations; parties depend on broad fundraising networks

Interest groups and political parties, while both integral to the political landscape, diverge significantly in their funding mechanisms. Interest groups, often advocating for specific causes or industries, primarily sustain themselves through targeted donations. These contributions typically come from individuals, corporations, or other organizations with a vested interest in the group’s mission. For instance, environmental interest groups might receive funding from eco-conscious philanthropists or green energy companies, while labor unions fund groups advocating for workers’ rights. This reliance on donations allows interest groups to maintain a laser focus on their niche objectives but also ties their financial health to the whims of their donor base.

In contrast, political parties operate within a broader financial ecosystem, leveraging extensive fundraising networks to secure resources. Unlike interest groups, parties aim to appeal to a wide spectrum of voters, necessitating diverse funding streams. These networks often include grassroots donations from individual supporters, high-dollar contributions from wealthy donors, and revenue from party-affiliated events or merchandise. For example, during election seasons, parties may host gala dinners or sell branded merchandise to bolster their coffers. This multifaceted approach ensures financial stability but also requires parties to balance the interests of various contributors, sometimes at the risk of diluting their core message.

A critical distinction lies in the scale and scope of these funding models. Interest groups, with their narrower focus, often rely on fewer but more substantial donations, making them susceptible to funding fluctuations if key donors withdraw support. Political parties, however, benefit from a larger donor pool, reducing their vulnerability to individual funding shifts. This difference highlights the trade-off between specialization and stability in financial strategies. For instance, while an interest group advocating for gun control might secure a large donation from a prominent activist, a political party can aggregate smaller contributions from thousands of supporters, creating a more resilient financial base.

Practically, this funding disparity influences the operational capabilities of both entities. Interest groups, with their donation-dependent model, may allocate resources more flexibly, focusing on specific campaigns or initiatives. Political parties, constrained by the need to cater to a broad fundraising network, often distribute funds across a wider array of activities, from candidate campaigns to voter outreach programs. For those involved in political advocacy, understanding these funding dynamics is crucial. Interest groups might prioritize cultivating relationships with key donors, while parties should focus on expanding their donor base through inclusive engagement strategies.

Ultimately, the funding sources of interest groups and political parties reflect their distinct roles in the political ecosystem. Interest groups thrive on targeted financial support, enabling them to champion specific causes with precision. Political parties, on the other hand, rely on broad fundraising networks to sustain their multifaceted operations and appeal to a diverse electorate. Recognizing these differences not only clarifies their financial strategies but also underscores the unique challenges each faces in advancing their agendas. Whether you’re an advocate, donor, or observer, grasping these nuances can inform more effective engagement with these pivotal political actors.

Which Political Party Pushed for Tobacco Restrictions? A Historical Overview

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Interest groups aim to influence public policy on specific issues or for particular constituencies, while political parties seek to gain political power by winning elections and controlling government.

Interest groups typically have voluntary, issue-specific memberships open to anyone who supports their cause, whereas political parties are organized around broader ideologies and require formal affiliation or registration to participate fully.

No, political parties are directly involved in electoral campaigns, nominating candidates, and mobilizing voters, while interest groups focus on lobbying, advocacy, and sometimes endorsing candidates without directly running campaigns.