The two-party political system, dominant in many democracies like the United States, is increasingly criticized for its limitations and negative impacts on governance and representation. Critics argue that it stifles diverse viewpoints by funneling political discourse into two broad, often polarized ideologies, leaving little room for nuanced or alternative perspectives. This system tends to prioritize party loyalty over bipartisan solutions, leading to gridlock and inefficiency in addressing critical issues. Additionally, it marginalizes smaller parties and independent candidates, limiting voter choice and perpetuating a cycle where power oscillates between two dominant factions without significant structural change. These flaws raise questions about the system's ability to truly represent the will of the people and foster meaningful democratic progress.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Limited Representation: Marginalized voices often excluded, leading to inadequate policy reflection

- Polarization: Extreme ideologies dominate, stifling compromise and moderate solutions

- Gridlock: Partisan conflicts hinder legislative progress, causing governmental inefficiency

- Corporate Influence: Both parties reliant on big donors, skewing priorities

- Voter Disenfranchisement: Lack of alternatives discourages participation and engagement

Limited Representation: Marginalized voices often excluded, leading to inadequate policy reflection

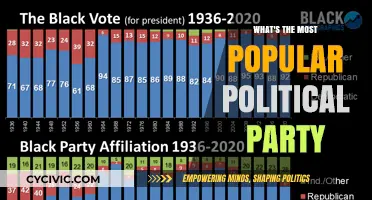

Marginalized communities—racial minorities, LGBTQ+ individuals, and low-income populations—are systematically underrepresented in the two-party system. A 2021 study by the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies found that only 12% of elected officials in the U.S. are Black, despite Black Americans comprising 14% of the population. This disparity isn’t accidental; it’s a byproduct of a system where major parties prioritize broad appeal over niche concerns. When parties focus on swing voters in battleground states, issues like police reform, transgender rights, or affordable housing often fall by the wayside. The result? Policies that fail to address the urgent needs of those most vulnerable.

Consider the legislative process itself, which amplifies this exclusion. In a two-party system, bills are often crafted through compromise between the dominant factions of the two parties. Marginalized groups, lacking strong representation within these factions, are rarely at the negotiating table. For instance, the 2017 tax reform bill disproportionately benefited high-income earners, while programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit—vital for low-income families—saw minimal expansion. This isn’t a failure of individual lawmakers but a structural flaw: when the system prioritizes bipartisanship over inclusivity, those on the margins are inevitably left behind.

To address this, practical steps can be taken. First, implement ranked-choice voting (RCV) in local and state elections. RCV allows voters to rank candidates in order of preference, reducing the "spoiler effect" and encouraging candidates to appeal to a broader spectrum of voters, including marginalized groups. Second, mandate diversity training for party leaders and campaign staff. A 2020 study by the Brookings Institution found that campaigns with diverse leadership teams were 20% more likely to address issues like racial justice and economic inequality. Finally, allocate public funding for community-based organizations to run candidates from underrepresented backgrounds. In New York City, a pilot program providing matching funds for small donations increased the number of candidates of color by 35% in the 2021 municipal elections.

Critics argue that these measures could fragment the political process, but the alternative—continued exclusion—is far more damaging. A system that fails to represent its most vulnerable citizens undermines its own legitimacy. Take the example of Native American communities, whose land and water rights are often ignored in federal policy. In 2020, only 1% of campaign spending by major parties targeted Indigenous issues, despite Native Americans making up 2% of the population. This isn’t just a moral failing; it’s a practical one. When entire communities are excluded from the policy-making process, the resulting laws are less effective, less equitable, and less sustainable.

The takeaway is clear: the two-party system’s limited representation isn’t just a theoretical problem—it’s a barrier to progress. By excluding marginalized voices, the system perpetuates policies that are out of touch with the lived experiences of millions. To build a more inclusive democracy, we must rethink the structures that silence these voices. Start small: advocate for RCV in your local elections, support candidates from underrepresented backgrounds, and demand diversity in party leadership. The goal isn’t to dismantle the two-party system overnight but to create cracks in its foundation—cracks through which marginalized voices can finally be heard.

Understanding Senior Voting Trends: Which Political Party Do Seniors Support?

You may want to see also

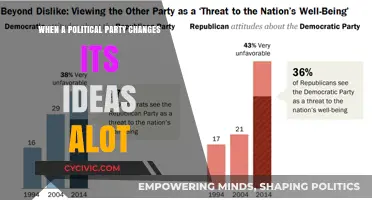

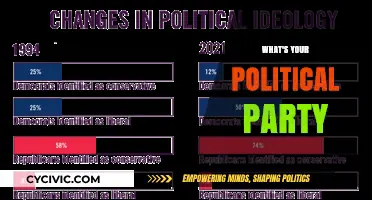

Polarization: Extreme ideologies dominate, stifling compromise and moderate solutions

In the United States, the two-party system has increasingly become a battleground for extreme ideologies, where the middle ground is not just overlooked but actively eroded. Consider the 2020 election, where terms like "socialism" and "fascism" were thrown around with alarming frequency, often stripped of their historical context and used as weapons to demonize the opposition. This hyperbole isn't just rhetorical flair—it reflects a deeper trend where politicians and their bases prioritize purity tests over practical solutions. For instance, a moderate proposal like infrastructure investment, which once enjoyed bipartisan support, now faces gridlock because one side fears it might be labeled as "too liberal" or "too conservative" by their extremist factions.

To understand how this polarization stifles compromise, imagine a legislative process as a recipe for governance. The ingredients—policies—are meant to be mixed in measured doses to create a balanced outcome. However, when extreme ideologies dominate, the recipe becomes a zero-sum game. For example, a bill addressing climate change might include both renewable energy incentives and protections for fossil fuel workers. In a polarized system, one party might reject it entirely because it doesn’t go far enough, while the other dismisses it as too radical. The result? A stalemate that leaves the problem unaddressed. Practical tip: Encourage your representatives to support "rule changes" like open primaries or ranked-choice voting, which can incentivize candidates to appeal to a broader electorate rather than just their party’s extremes.

The consequences of this polarization extend beyond Capitol Hill. At the local level, communities are torn apart as national partisan divides seep into school board meetings, zoning debates, and even public health discussions. Take the COVID-19 pandemic: Mask mandates and vaccine requirements became flashpoints, not because of scientific disagreement, but because they were framed as partisan issues. This isn’t just about policy—it’s about trust. When moderate solutions are dismissed as weak or traitorous, citizens lose faith in the system’s ability to solve problems. Caution: Avoid engaging in all-or-nothing thinking in your own political discussions. Acknowledge the validity of partial solutions, even if they don’t align perfectly with your ideals.

A comparative look at other democracies reveals that multiparty systems often foster more compromise. In Germany, for instance, coalition governments are the norm, forcing parties with differing ideologies to negotiate and find common ground. Contrast this with the U.S., where the winner-takes-all approach encourages parties to double down on their extremes to secure a majority. The takeaway here isn’t to dismantle the two-party system overnight but to recognize its limitations. Steps like campaign finance reform or redistricting commissions could reduce the incentives for polarization, but they require public pressure to implement.

Ultimately, the dominance of extreme ideologies in a two-party system creates a feedback loop: Polarization breeds gridlock, which fuels voter frustration, which in turn empowers more extreme candidates. Breaking this cycle requires a shift in mindset—from viewing politics as a war to seeing it as a collaborative effort. Start small: Engage with local initiatives that bring together diverse stakeholders to solve community problems. By modeling compromise in your own sphere, you contribute to a culture that values progress over purity. The system won’t change overnight, but every moderate solution adopted is a step toward a more functional democracy.

Switching Political Parties in New Hampshire: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Gridlock: Partisan conflicts hinder legislative progress, causing governmental inefficiency

Partisan gridlock has become a defining feature of the two-party political system, particularly in the United States, where legislative progress often stalls due to ideological entrenchment. Consider the 2013 federal government shutdown, which lasted 16 days and cost the economy an estimated $24 billion. This shutdown occurred because Democrats and Republicans could not agree on a budget, with the Affordable Care Act as the central point of contention. Such instances illustrate how partisan conflicts prioritize political victory over governance, leaving critical issues unresolved and public trust eroded.

To understand gridlock, examine the mechanics of the two-party system. When power is concentrated between two dominant parties, compromise becomes a liability rather than a virtue. For example, a legislator who crosses party lines risks backlash from their base, primary challenges, or loss of committee assignments. This dynamic discourages collaboration and incentivizes obstruction. In the 116th Congress (2019–2021), only 5% of bills introduced became law, a stark indicator of how partisan divisions stifle productivity. The system’s structure effectively rewards rigidity, making gridlock not an anomaly but a predictable outcome.

Breaking gridlock requires systemic changes, but incremental steps can mitigate its effects. One practical approach is to adopt bipartisan legislative rules, such as open amendments or consensus-driven committee processes. For instance, the Problem Solvers Caucus in the House of Representatives pairs equal numbers of Democrats and Republicans to negotiate solutions on contentious issues. Another strategy is to empower independent or third-party candidates by reforming election laws, such as implementing ranked-choice voting, which encourages candidates to appeal to a broader electorate. While these measures won’t eliminate gridlock, they can create pathways for progress in an otherwise polarized environment.

Ultimately, gridlock is a symptom of a deeper issue: the two-party system’s tendency to reduce complex issues to binary choices. This simplification fosters an "us vs. them" mentality, where compromise is seen as betrayal rather than statesmanship. Until structural reforms address this root cause, gridlock will persist, undermining the government’s ability to respond effectively to crises. The takeaway is clear: without reimagining the political landscape, partisan conflicts will continue to hinder legislative progress, leaving citizens to bear the cost of governmental inefficiency.

The Evolution of America's Two-Party System: A Historical Overview

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$24.71 $36.99

Corporate Influence: Both parties reliant on big donors, skewing priorities

In the United States, the two major political parties raise billions of dollars each election cycle, with a significant portion coming from corporations, industry groups, and wealthy individuals. For instance, during the 2020 election, corporate PACs and individuals giving over $10,000 accounted for nearly 60% of total federal campaign contributions. This financial reliance creates a system where policymakers are more likely to prioritize the interests of their donors over those of the general public. Consider the pharmaceutical industry, which spent $295 million on lobbying in 2020 alone, successfully blocking legislation that would allow Medicare to negotiate lower drug prices—a policy supported by 86% of Americans.

To understand the mechanics of this influence, examine the concept of "access lobbying." When a corporation donates substantial sums to a political party or candidate, it often gains privileged access to lawmakers through private meetings, exclusive events, and advisory roles. This access allows donors to shape policy discussions behind closed doors, where public scrutiny is minimal. For example, the financial sector’s $3.4 billion in political spending from 2010 to 2020 coincided with the watering down of Dodd-Frank regulations and the rollback of consumer protections. Such access skews policy priorities, as lawmakers spend disproportionate time addressing donor concerns rather than constituent needs.

A comparative analysis of campaign finance systems highlights the severity of this issue. In countries with stricter donation limits and robust public financing, such as Canada and Germany, corporate influence on policy is significantly reduced. Canada caps individual donations at $1,650 annually and provides public funds to parties based on election performance, ensuring that parties remain accountable to voters rather than donors. Contrast this with the U.S., where Super PACs can accept unlimited contributions, enabling corporations to funnel millions into elections without transparency. This disparity underscores how the two-party system’s reliance on big donors distorts democratic representation.

To mitigate corporate influence, practical steps can be taken at both the legislative and grassroots levels. First, implement a constitutional amendment to overturn *Citizens United*, which allows unlimited corporate spending in elections. Second, establish a small-donor public financing system, where candidates who agree to spending limits receive matching funds for small donations. This would incentivize politicians to focus on grassroots supporters rather than wealthy donors. Finally, voters must demand transparency by supporting candidates who refuse corporate PAC money and advocating for real-time disclosure of campaign contributions. Without such reforms, the two-party system will continue to prioritize corporate interests over public welfare.

Unveiling the Political Party of Our Current President: A Comprehensive Overview

You may want to see also

Voter Disenfranchisement: Lack of alternatives discourages participation and engagement

In a two-party system, voters often find themselves trapped between two dominant political entities, neither of which fully aligns with their beliefs. This lack of alternatives breeds disillusionment, as citizens feel their voices are reduced to a binary choice. For instance, a voter who prioritizes environmental policies but disagrees with a party’s stance on healthcare may feel forced to compromise core values. This forced compromise discourages participation, as voters perceive their options as limited and unsatisfying. When the ballot box fails to reflect diverse ideologies, engagement wanes, and democracy suffers.

Consider the mechanics of voter behavior: when alternatives are absent, the act of voting becomes an exercise in lesser-evil selection rather than meaningful representation. This dynamic disproportionately affects younger voters, aged 18–29, who often seek progressive or innovative solutions not championed by the two dominant parties. Studies show that this age group has the lowest voter turnout in many two-party systems, not due to apathy, but because they feel their choices are irrelevant. Practical steps to address this include lowering barriers to third-party participation, such as reducing ballot access requirements and implementing ranked-choice voting, which allows voters to express nuanced preferences.

The persuasive argument here is clear: a two-party system stifles political innovation and alienates voters who crave alternatives. Compare this to multi-party democracies, where smaller parties can gain traction and influence policy debates. In Germany, for example, the Green Party has shaped national climate policy, attracting voters who feel heard. In contrast, the U.S. system often marginalizes third parties, leaving voters with no outlet for their ideals. This structural flaw not only discourages participation but also perpetuates a cycle of political stagnation, as fresh ideas struggle to gain visibility.

To combat voter disenfranchisement, actionable measures are essential. First, educate voters on the impact of their participation, even in a flawed system. Second, advocate for electoral reforms that level the playing field for third parties. Third, encourage local engagement, where smaller-scale politics often offer more diverse representation. By addressing the root cause—the lack of alternatives—we can reignite civic engagement and restore faith in the democratic process. Without these changes, the two-party system will continue to alienate voters, undermining the very foundation of participatory democracy.

When Politics Divides: Healing Quotes for Fractured Friendships

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The two-party system tends to marginalize smaller parties and independent candidates, reducing the range of political ideologies and policies available to voters. This can lead to a lack of representation for minority viewpoints and stifle innovative solutions to complex issues.

The two-party system often encourages extreme positions as parties cater to their bases to secure votes, leading to gridlock and divisiveness. This polarization discourages compromise and makes it harder to address pressing national issues effectively.

Many voters feel alienated by the lack of meaningful choices, as the two major parties often fail to represent their interests or values. This can lead to lower voter turnout and disengagement from the political process.

The dominance of two parties often leads to a concentration of political power and funding, making it easier for wealthy donors and special interest groups to influence policy. This undermines the principle of equal representation and prioritizes the agendas of the powerful over the needs of the general public.